“L-L-Lowell, the English are the result of too much proper breeding,” said Oliver Sacks, neurologist and author, in December 1987. It was my first trip overseas. I was in my early thirties, Oliver in his mid-fifties, and I was working as his photographer.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but that sentence would stand not only as a joke about the English, but also as a partial explanation for how Oliver understood himself. He was shy and very polite, even restrained in many ways, the product of a medical and Jewish aristocracy. Oliver’s mother was a surgeon, and his cousin was the Israeli diplomat Abba Eban. When I met Oliver’s father that same year, the elder Dr. Sacks was ninety-two years old and still practicing medicine at the house in London where Oliver was raised. As Oliver explains in his last book published during his lifetime, On the Move, he rebelled against this upbringing and arrived in San Francisco leather clad on a motorcycle. He later moved to Los Angeles, where he was a resident in neurology at UCLA, feasting on hallucinogens and the endorphin highs of weight-lifting.

Oliver’s 1985 book The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat had just become a best-seller when I first contacted him. I’d read the book, which included Sacks’s study of a drummer with Tourette’s syndrome, with great interest. At the time, Oliver lived on City Island and his number was listed in the phone book. I called him up, and he answered. I explained, “I’m the only one who’s photographing people with Tourette’s, and you’re the only one writing about it. And I have Tourette’s. Let’s get together.” He agreed.

We were close for a long time. I was his photographer, colleague, friend, subject, and occasional collaborator. He used to say that he wanted to take off his white doctor’s coat and see Tourette’s in real life, outside a clinic or hospital. I facilitated this not only as a photographer, but also as someone with access to others with the same condition. In my travels with Oliver, I photographed the lives of patients, beyond the confines of the doctor’s office or examination room. Some said I was his “Tourette pet,” which I found endearing or insulting, depending on how it was said.

Together we traveled to Europe, Canada, and across the United States. As we got to know each other well, I learned that Oliver was writing about me in his notebooks, while at the same time I was busy photographing him, linking us in a bond of mutual observation and reflection. Our relationship became complicated.

We had just finished a collaborative article, published first in Life magazine and then internationally, about an extended Mennonite family in northern Alberta, Canada, whose members were disproportionately affected by Tourette’s and an overlapping Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. I photographed the story, while Oliver wrote it as if seen through my lens. After hearing me repeat names and phrases, Oliver wrote that an aspect of my Tourette’s was being fascinated by the “acoustic contours” of words and language.

Oliver was never my physician, and although there were times I wondered if I would trust him with a prescription for Vitamin C, I half hoped he would one day present me with a magic pill to cure my Tourette’s. What he gave me instead was much more: an insight into myself, a window into his own quirky personality, and a new awareness of aspects of human nature.

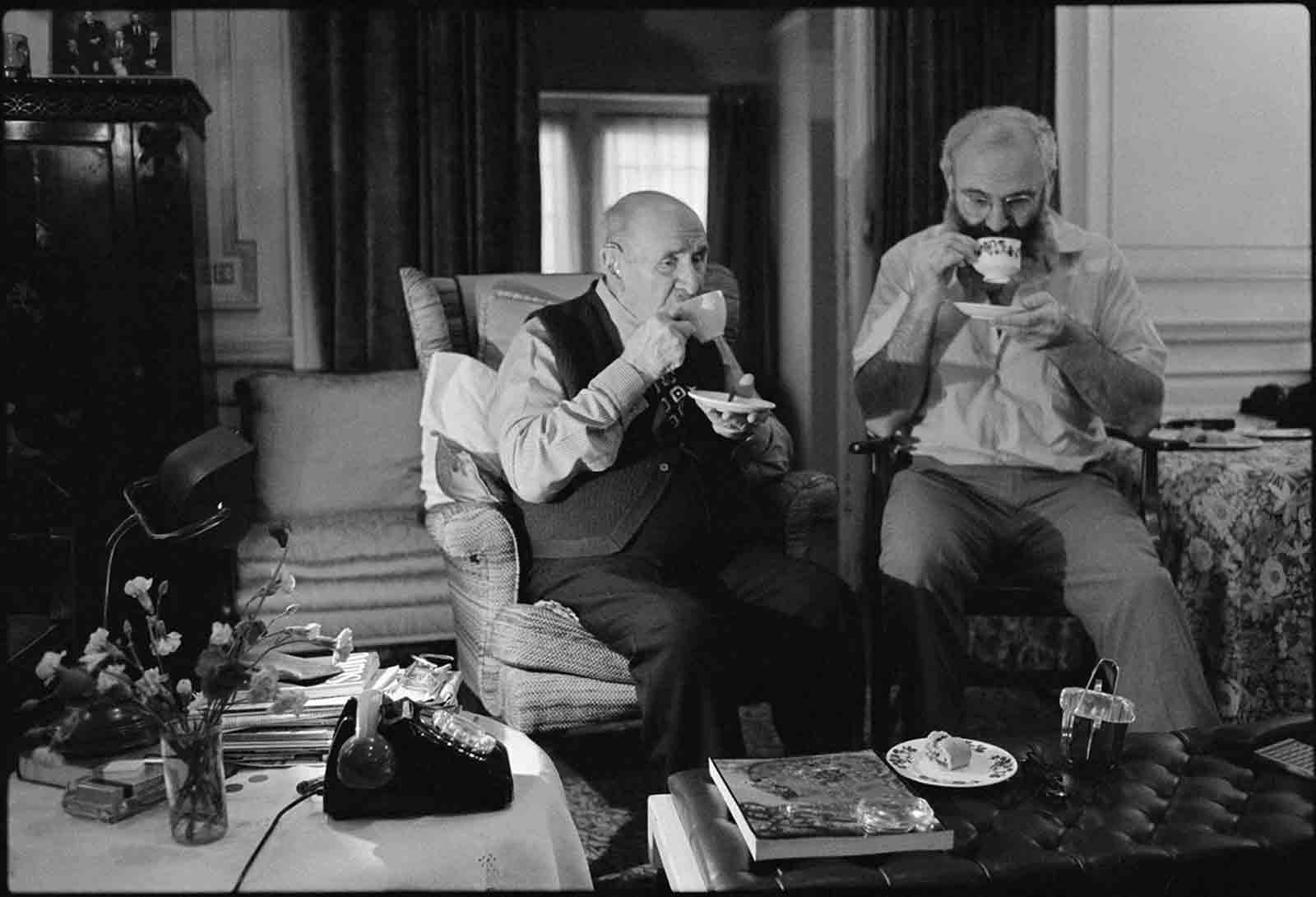

In London, Oliver introduced me to his father, and the old man stared, eyes bulging, at my gyrations, twitches, head jerking, and barking, then turned to Oliver and said, “Quite remarkable, Oliver. What is it?” Oliver explained, “He has Tourette’s Syndrome, Pop, one of the things I have been writing about.” I thought it odd at the time that his father didn’t just ask me. And I thought it was cute that Oliver called his father Pop.

Between 1987 and 1989, Oliver and I had a working relationship, traveling together around the US, Canada, and Europe. Some of my favorite memories of those travels with Oliver were the holidays in the Netherlands.

Upon landing in Holland early one December morning in 1987, we met our Dutch host, a doctor named Ben van de Wetering who was studying some of the same conditions as Oliver. Ben, a large man with a big beard like Oliver’s, worked at a medical center and lived with his family in a small village outside Rotterdam. He took us out for breakfast that first morning in Amsterdam and later invited us to his home, where we watched his wife and young children play together.

Advertisement

The conditions Ben and Oliver were looking at—like Tourette’s Syndrome, all neuropsychological—were believed to be part of a continuum of abnormalities located mainly in the brain’s frontal lobes. Chemicals called neurotransmitters misfiring at the synapses, either in excess or deficiency, caused the symptoms. With Tourette’s, the result of an over-abundance of the neurotransmitter dopamine, the entire spectrum of the disorder can be defined as uncontrolled disinhibition. This lack of inhibition is not limited to movement, but also language, noise, speech, and even thought.

Ben explained that in the Netherlands, many people with neurological disorders like Tourette’s felt alienated and marginalized. “There are treatment options. Some don’t seek treatment, but rather live in denial and isolation.” Ben was less analytical than compassionate and engaged. He was also active in helping the local Tourette’s Syndrome chapter and support group, which Oliver and I sat in on one evening at the hospital.

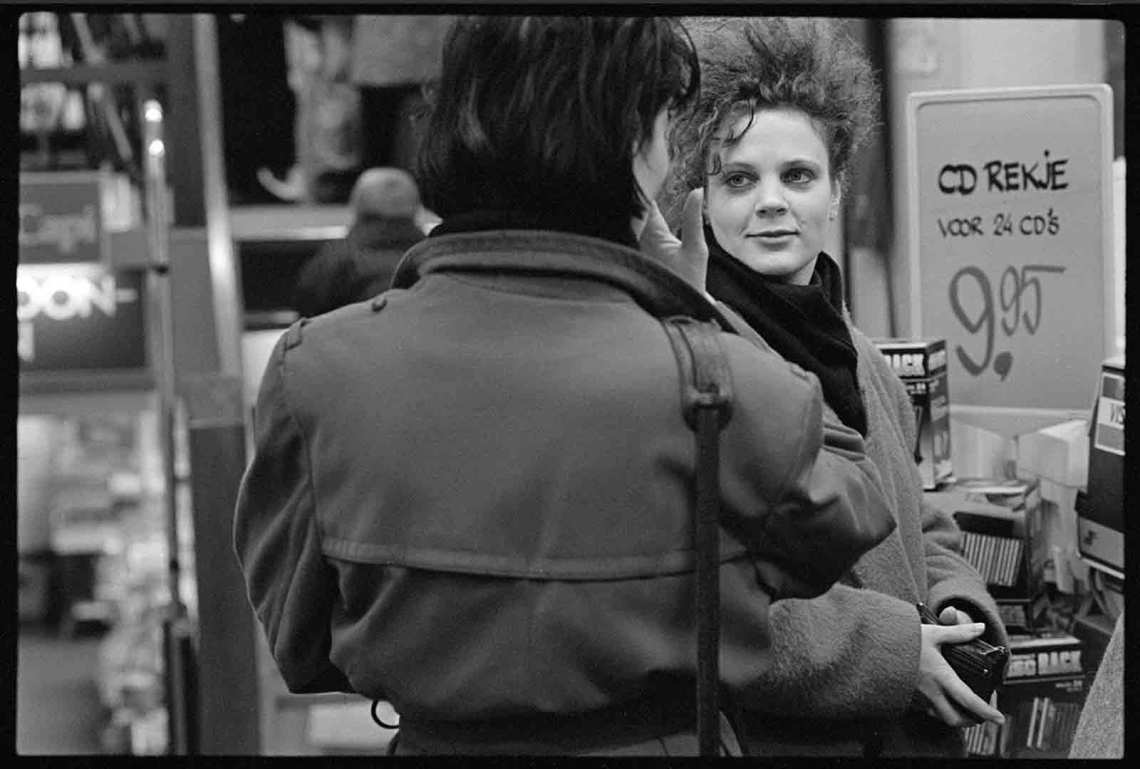

“It is completely useless,” a man shouted out, referring to his Tourette’s symptoms. Alan had minimal involuntary movements of his arms and legs but shouted out words and phrases. He continued his rant, “Why do we do these things?” A woman was sitting across the table from me smoking a cigarette, an exaggerated series of gestures brought on by this dopamine blast. She was young, in her mid-twenties, and spoke English well. When she, Ben, Oliver, and I strolled together down the halls of the hospital, she said, “to Tourette is like to pirouette.” Both Ben and Oliver chuckled.

In Amsterdam, we stayed downtown at a beautiful hotel on a canal. One morning, Oliver asked if I’d like to appear on television with him. He had been contacted by one of the country’s leading intellectuals, Adriaan van Dis, who had a well-known talk show and had been interviewing public figures, mostly writers, for decades. Oliver was inhibited in many ways, and this I believe is one of the reasons he was so drawn to those of us with Tourette’s. It also led him to substances that would relax him, relieving him from his feelings of self-consciousness.

After we had drinks to loosen up a bit, we went on the show. Oliver spoke, among other things, about Awakenings, a book he wrote in the early 1970s that had been made in 1990 into a film starring Robin Williams as Oliver and Robert De Niro as a patient. Adriaan van Dis introduced me and asked me about Tourette’s Syndrome. He wanted to know how it affected me and in what contexts I had experienced the symptoms.

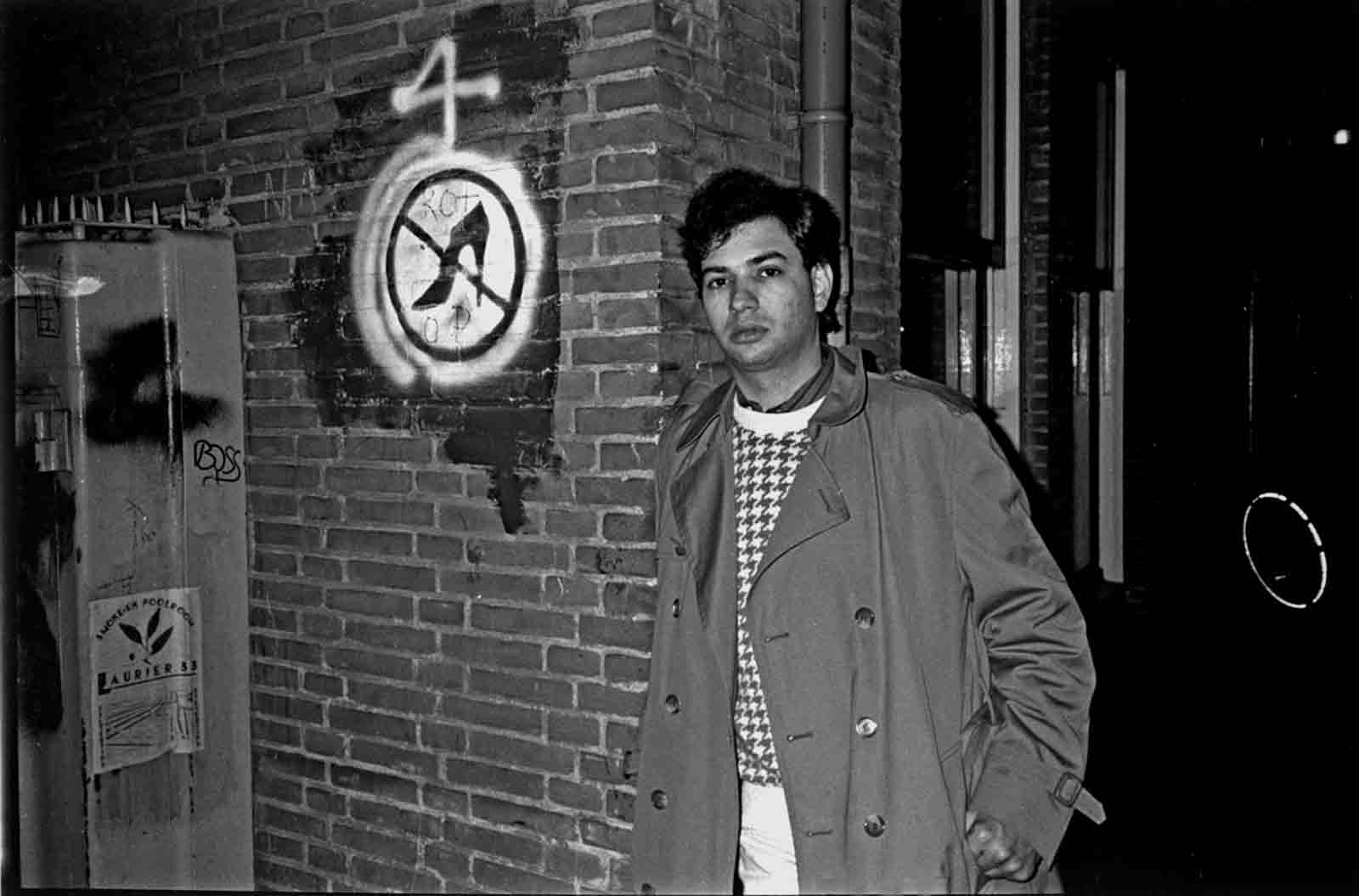

For the next few days, it seemed that everywhere we went, people stopped, stared, and pointed. In such a small country, with few TV channels, a huge percentage of the population must have been watching. Oliver and I decided it was time to see the more subterranean side of the city.

We set out on foot for the bars and coffee houses that fill almost every block selling food, coffee, alcohol, hash, and pot. We found a café and ordered dinner as we pondered a trip through the red-light district. The bartender showed us a billfold of various strains of marijuana, each with its own name and price. We picked one and rolled a joint. In the Netherlands at the time, most people used a combination of tobacco and pot, sometimes with ground-up hashish resin as well.

Our next stop was a bar overflowing with people. As soon as we entered, a woman who had obviously been there drinking for some time announced to Oliver, “We have read all your books and we love you!” A small crowd around her cheered. Oliver and I stepped up to the bar and ordered drinks. The woman patted Oliver on the back and offered to buy us a round.

At the red-light district, we waved back to the women sitting in the windows. After walking what seemed like miles, we came upon a huge nightclub called The Milky Way. It was getting late, but we went in.

Couches lining the walls were littered with people in various states of consciousness. We went to the bar for drinks, some hashish, and more pot. Here, people again seemed to recognize us, at least Oliver, but this time the patrons were not as complimentary. An old man, obviously drunk, looked right at Oliver and said, “We are sick of you and your weird diseases, go home!” Oliver suggested we move to the other end of the bar.

Advertisement

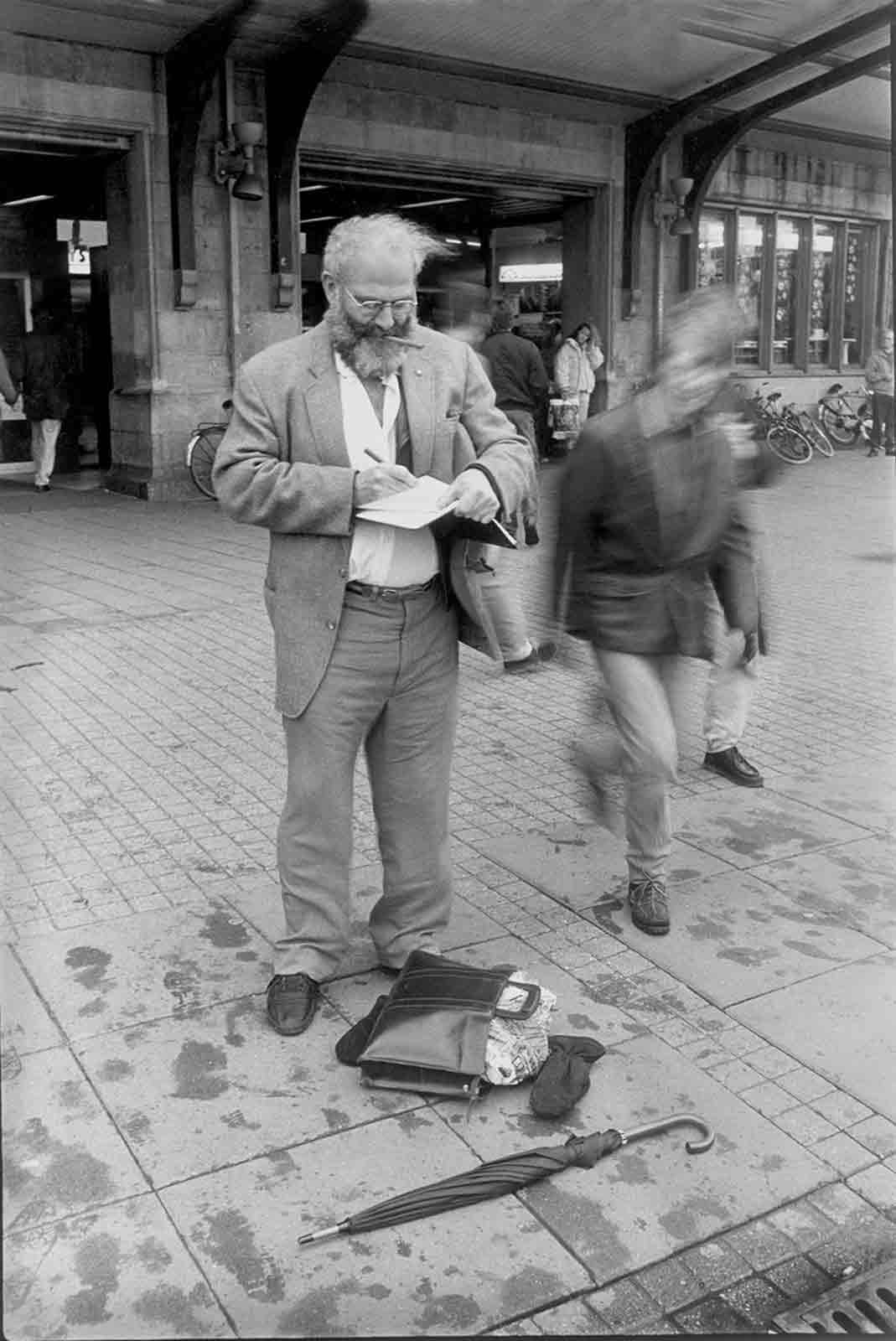

We didn’t stay at The Milky Way long, but drifted to other bars, smoking and drinking all night. Eventually, we decided to go for a walk. For hours we walked, with Oliver often stopping to write in his notebook, while I photographed. Oliver gave me some good advice: “Lowell, when someone asks, just say you are neuropsychologically different.”

As the first rays of light were streaking across the sky, we made our way back toward the hotel, stumbling somewhat, until I finally noticed there was no film in my camera, and Oliver realized his own handwriting had become indecipherable.

Ascending the stairs to our rooms, I asked Oliver not to wake me until noon the next day, gave him the one remaining piece of hash, and said goodnight.

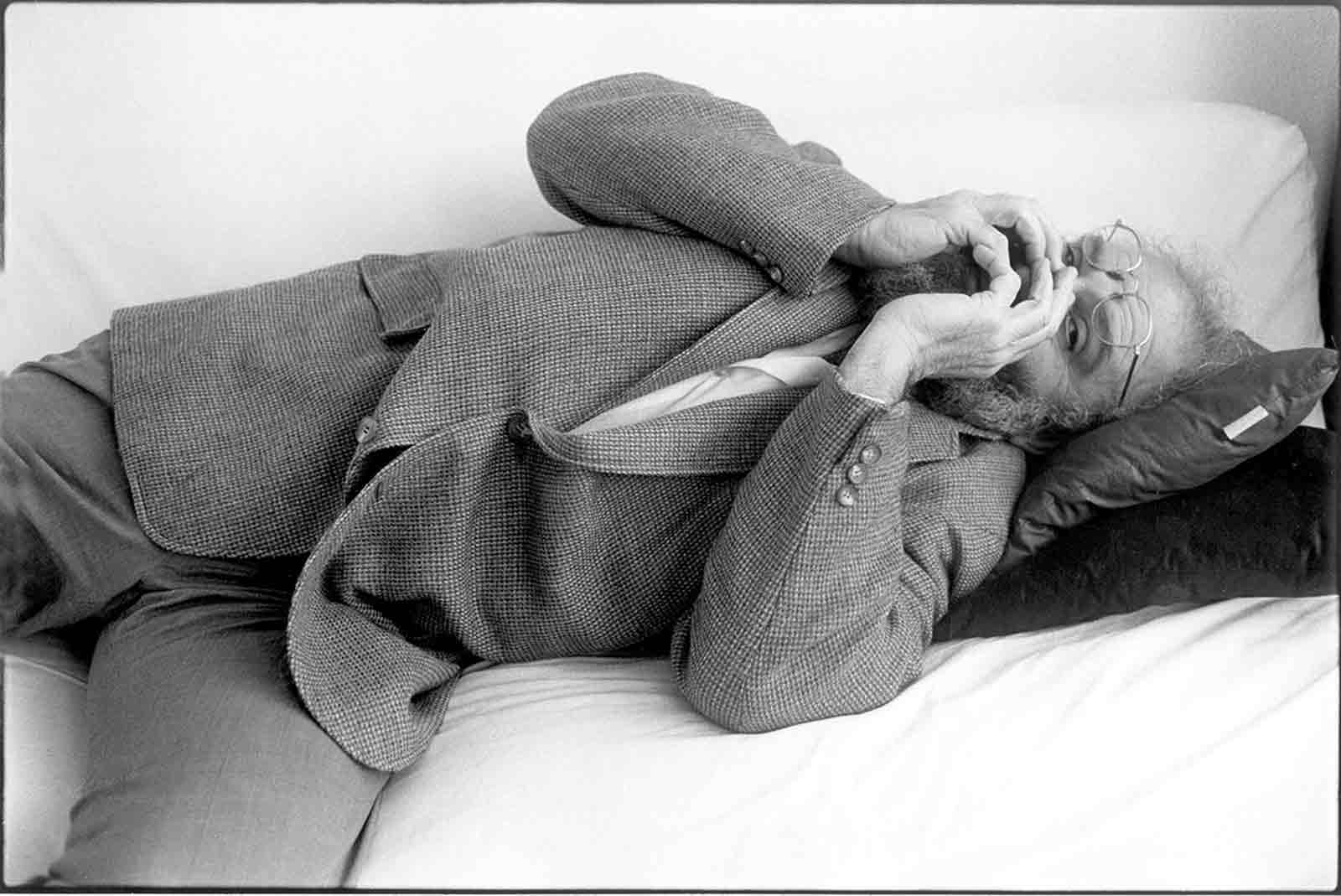

At exactly 12 PM the following day, there was a knock. I opened the door and found Oliver, his hair wildly unkempt, his glasses crooked, his shirt all wrinkled, and his pants twisted. I looked in his eyes, which were bloodshot and half-closed, and said, “Oliver, where have you been?” He answered, “I fear I wandered about the city all night and day, smoked the rest of the hash, and had some more to eat and drink.” He had been walking for many hours, drunk and stoned, a physical wreck, and he still wanted more of everything. It made me think of Oscar Wilde—“Moderation is a fatal thing. Nothing succeeds like excess.”—and I remembered what Oliver had told me a grade school teacher had written on his report card: “Sacks will go far, if he does not go too far.”

In our later years, we remained friends, getting together from time to time for meals, events, and gatherings with colleagues and mutual friends. As we got older, we each changed to an extent, the way people do over time. What we still had in common were not only the past places and people we knew together, but also the shared experience of “otherness.” With Oliver’s painful shyness and reticence sometimes preventing him from social interaction, and the physicality of my Tourette’s symptoms, having shared the experience of being an outsider we understood one another.

The last time I saw Oliver, then eighty-one, was in Brooklyn. He was with his partner, Billy Hayes, at The Valley of Astonishment, a play about synesthesia written and directed by Peter Brook and Marie-Hélène Estienne. I approached them in the lobby and said to Oliver, “I don’t remember you getting old.” He said, “I did anyway.” A few months later, a package arrived with his memoir, On the Move, and a handwritten letter telling me of plans for a future book that would include our travels together. Oliver wrote, “It may be posthumous, as I do not know how long I have.”

Lowell Handler is featured in Ric Burns’s forthcoming documentary Oliver Sacks: His Own Life, coming in April 2021 to PBS’s “American Masters” series.