David Rieff went to Bosnia in September 1992, at the end of the first summer of siege. Like so many of the journalists who made the journey to Sarajevo, he did so because he believed, however implicitly, in the existence of a civilized world and in the duty to inform it. “If the news about Bosnia could just be brought home to people,” he thought, “the slaughter would not be allowed to continue. In retrospect, I should have known better than to believe in the power of unarmed truths.”

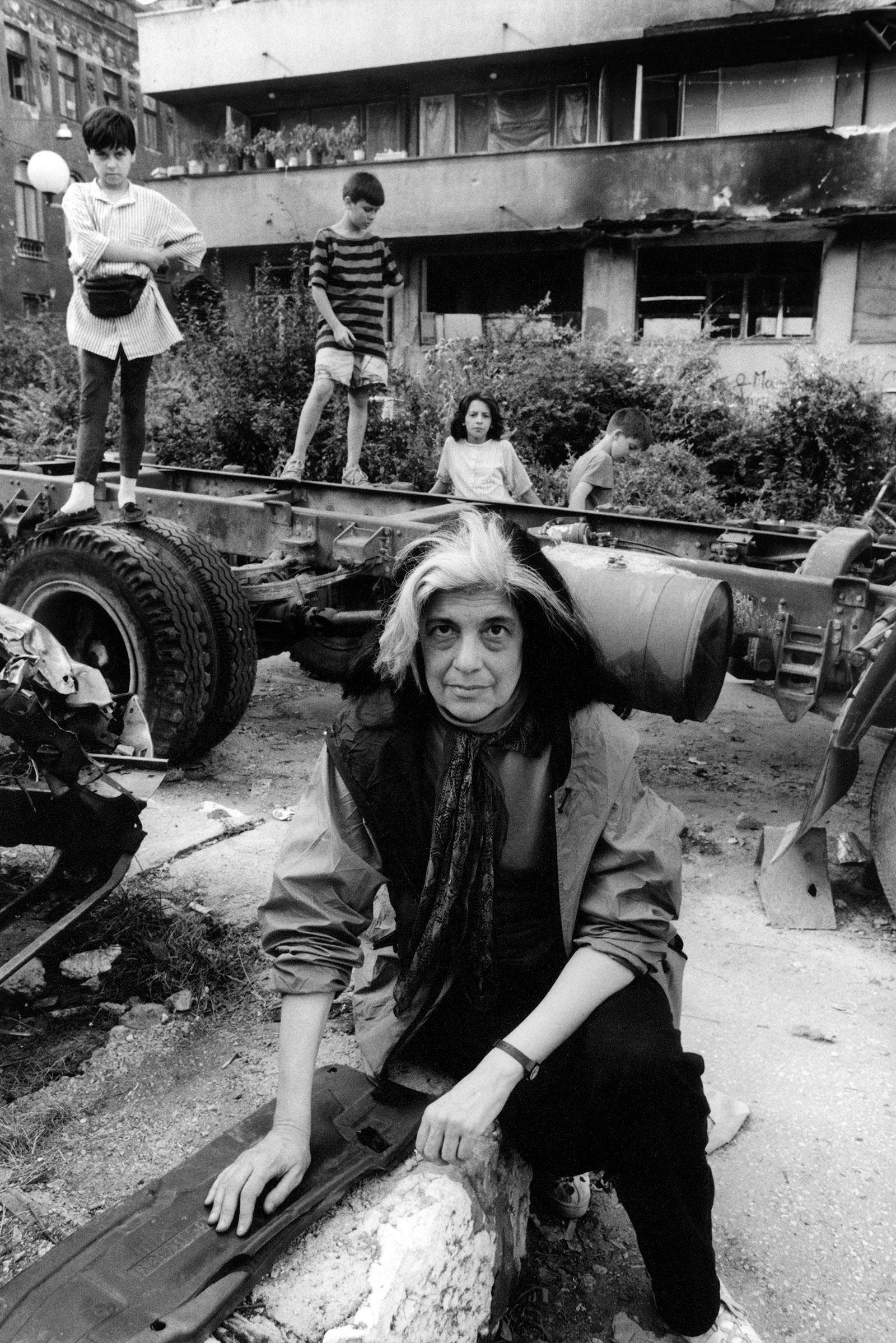

At the end of that first visit, he spoke to Miro Purivatra, who later founded the Sarajevo Film Festival, and asked if there was anything, or anyone, he could bring back. “One of the persons who could be perfect to come here to understand what’s going on would definitely be Susan Sontag,” he said. Without mentioning the connection—“for sure,” Miro said, “I did not know that he was her son”—David said he would do what he could. He appeared at Miro’s door a few weeks later. “We hugged each other and he told me, ‘Okay, you asked me something and I brought your guest here.’ Just behind the door, it was her. Susan Sontag. I was frozen.”

It would be at least a month before he figured out their relationship: “They never told me.” The first of what would turn out to be Susan’s eleven visits to a place that became so important to her life that a prominent downtown square is today named for her—so important that David would consider burying her there—took place in April 1993.

As Sarajevo was situated at the intersection between Islam and Christianity, and between Catholicism and Orthodoxy, it was the place where the interests that Sontag had pursued throughout her life coincided. The political role, and the social duty, of the artist; the attempt to unite the aesthetic with the political, and her understanding that the aesthetic was political; the link between mind and body; the experience of power and powerlessness; the ways pain is inflicted, regarded, and represented; the ways images, language, and metaphor create—and distort—whatever people call reality: these questions were refracted, and then literally dramatized, during the nearly three years she spent coming and going from the worst place in the world.

“I didn’t not come before because I was afraid, I didn’t not come because I wasn’t interested,” Susan said on that first visit. “I didn’t come before because I didn’t know what’s the use of it.” But once she left, she could not get the city out of her mind. The contrast between what she had seen and the cool indifference of the world outside was too jarring. Safe in Berlin, she found herself “totally obsessed,” writing to a German friend that “to go to Sarajevo now is a bit like what it must have been to visit the Warsaw Ghetto in late 1942.”

The comparison to the Holocaust was not made flippantly—and when the massacres, concentration camps, and “ethnic cleansing” came to light, it would become commonplace. But Susan saw it immediately. “She was the first international person who said publicly that what is happening in Bosnia in 1993 was a genocide,” said Haris Pašović, a young theater director. “The first. She deeply understood this. She was absolutely 100 percent dedicated to this because she thought it was important for Bosnia but it was also important for the world.”

What was at stake in Sarajevo was not only the fate of a people and a country. Sarajevo was a European city—and Europe, David wrote, “had become a moral category as well as a geographical one.” This category was the liberal idea of the free society: of civilization itself. The Bosnians knew this and were bewildered that their appeals were met with such indifference. The idea of Europe that they defended had emerged from the Holocaust, after which the basic measure of civilization became the willingness to resist the kinds of horrors unfolding in Bosnia. After Auschwitz, the civilized government was one defined by its resistance to these crimes; and governments were not the only ones called: the free citizen, too, had an obligation to resist. But how could a single person stand in the path of a genocidal army?

The question of how to oppose injustice had occupied Susan since childhood: since she read Les Misérables, since she saw the first pictures of the Holocaust in the bookstore in Santa Monica. Sarajevo offered a chance to put her body on the line for the ideas that had given dignity to her life. This was what she had not been able to do with AIDS—but she did now, and Pašović saw how far she was willing to go.

Advertisement

The locals had ample opportunities to size up their visitors. Some, whose intentions were beyond reproach, offended the Sarajevans. Amid widespread starvation, Joan Baez warned the local journalist Atka Kafedzić that she was “too skinny”; Bernard-Henri Lévy, known in France as BHL, became known in Bosnia as DHS—“Deux Heures à Sarajevo,” Two Hours in Sarajevo.

“We were very cynical about the whole circus element of these war safaris,” said Una Sekerez, who issued passes on behalf of the United Nations, and provided Susan with one:

There were other people like that, like: What are they doing here? I just assumed she was in for a quick look at how these people on the reservation lived—and she would go. Then she stayed. That was very, very unusual.

On that first visit, the poet Ferida Duraković translated questions from a journalist.

His first question was: How do you feel coming to Sarajevo for safari? I translated it and Susan said: I understood the question. Please be careful when you translate this. She looked at me and then said, “Young man, don’t put stupid questions. I am a serious person.”

*

“Witnessing requires the creation of star witnesses,” Sontag wrote in Regarding the Pain of Others, the last book published in her lifetime. Like so many of her works, the book was a meditation on ways of seeing and representing; but if her reference to stars sounded sardonic, it was not—or not only. Like all forms of seeing and representing, witnessing was often pathetically ineffective. How was watching something happen, even risking one’s life to write about it or take pictures of it, going to change the world of armies and politics?

Yet the New York Times reporter John Burns saw the importance of witnesses. Shortly after the siege of Sarajevo began, three journalists were killed; and the remaining reporters, led by the BBC, decided that they should all leave: “It was an intense, shameful debate.” They evacuated to the suburb of Ilidža, safely beyond the airport, to the same hotel where Archduke Franz Ferdinand slept before his own apocalyptic visit. There, Burns made up his mind to go back to Sarajevo. “As soon as we left, the Serbs started letting loose on the city,” he explained. “Ten thousand shells that day. They [the Serbian forces] felt free because the journalists were gone.”

Eyes made a difference, even if only a limited one. In On Photography, Susan discussed the limits of representing calamity. “A photograph that brings news of some unsuspected zone of misery cannot make a dent in public opinion unless there is an appropriate context of feeling and attitude.” This allowed a witness—a writer, a journalist, a photographer—to create that context; but that process could be agonizingly slow, and it was not easy to know if one was making any difference. “No longer can a writer consider that the imperative task is to bring the news to the outside world,” she wrote. “The news is out.”

This was what David discovered. Everyone everywhere knew what was happening in Bosnia, yet few went beyond rhetorical expressions of solidarity. The politicians relied on compassion fatigue, exactly as Susan had warned in On Photography—photographs of war would become nothing more than “the unbearable replay of a now familiar atrocity exhibition.” She recorded how the victims, enraged by the world’s apparent indifference, mocked the powerless newsbringers, whether celebrities or journalists:

In Sarajevo in the years of the siege, it was not uncommon to hear, in the middle of a bombardment or a burst of sniper fire, a Sarajevan yelling at the photojournalists, who were easily recognizable by the equipment hanging round their necks, “Are you waiting for a shell to go off so you can photograph some corpses?”

The reporters who were risking their lives for the sake of Sarajevo were judged. And they, likewise, judged those they suspected of tourism. But both Sarajevans and journalists respected Susan Sontag. One, the American Janine di Giovanni, was amazed by her sheer stamina:

It was unbelievably tough for me, a twenty-something-year-old girl. And she was a woman in her sixties. It really struck me. For a New York intellectual it was an odd place to be. Lots of celebrities came, and the reporters were cynical. I remember hearing she was coming and not being that impressed. But she didn’t complain. She sat with everyone else, she ate the crap food, she lived in the bombed-out rooms we lived in.

On her first visit, she asked Ferida Duraković to organize a meeting with intellectuals. Duraković invited some people who brought predictable requests for material assistance—which, in time, Susan would provide. “But what do you want me to do,” she asked, “besides bringing food, or money, or water, or cigarettes? What do you want from me?”

Advertisement

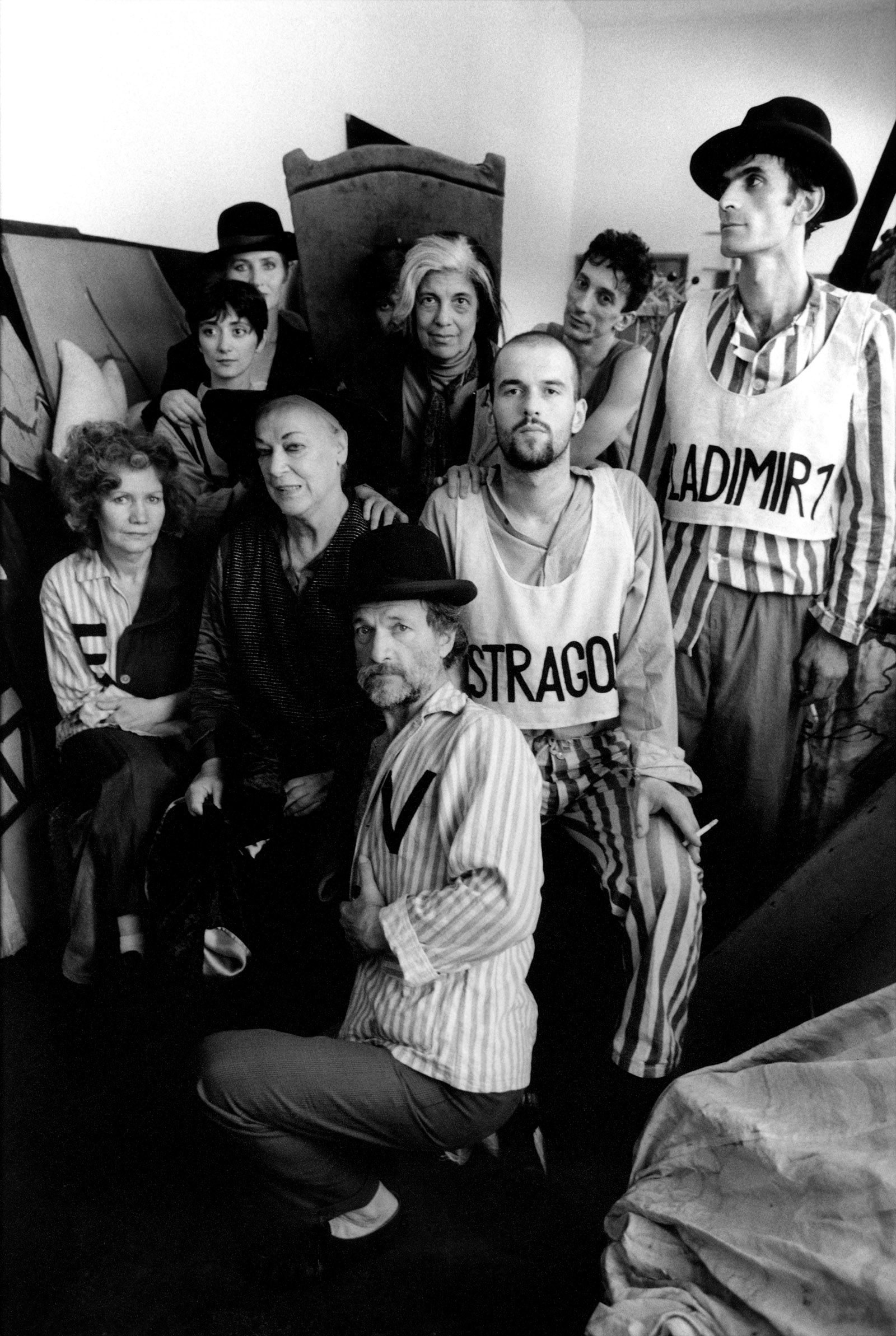

Eventually, with Pašović, head of the International Theater Festival, she discussed putting on a play. This would by no means liberate the city. But it did have some practical use. It would offer employment to actors, provide cultural activity, and show the world that the supposedly barbarous clans of Yugoslavia were every bit as modern as the people who might read of the production in their newspapers. She considered Ubu Roi, the play by Alfred Jarry that is often considered the grandfather of modernist theater. And she mentioned Happy Days, Beckett’s play about a woman chattering with her husband, remembering happier days, while being buried alive. The dirt reaches her neck by the end of the play.

“She came with Beckett,” Pašović remembered. “And I said: But Susan, here—in Sarajevo—we are waiting.”

*

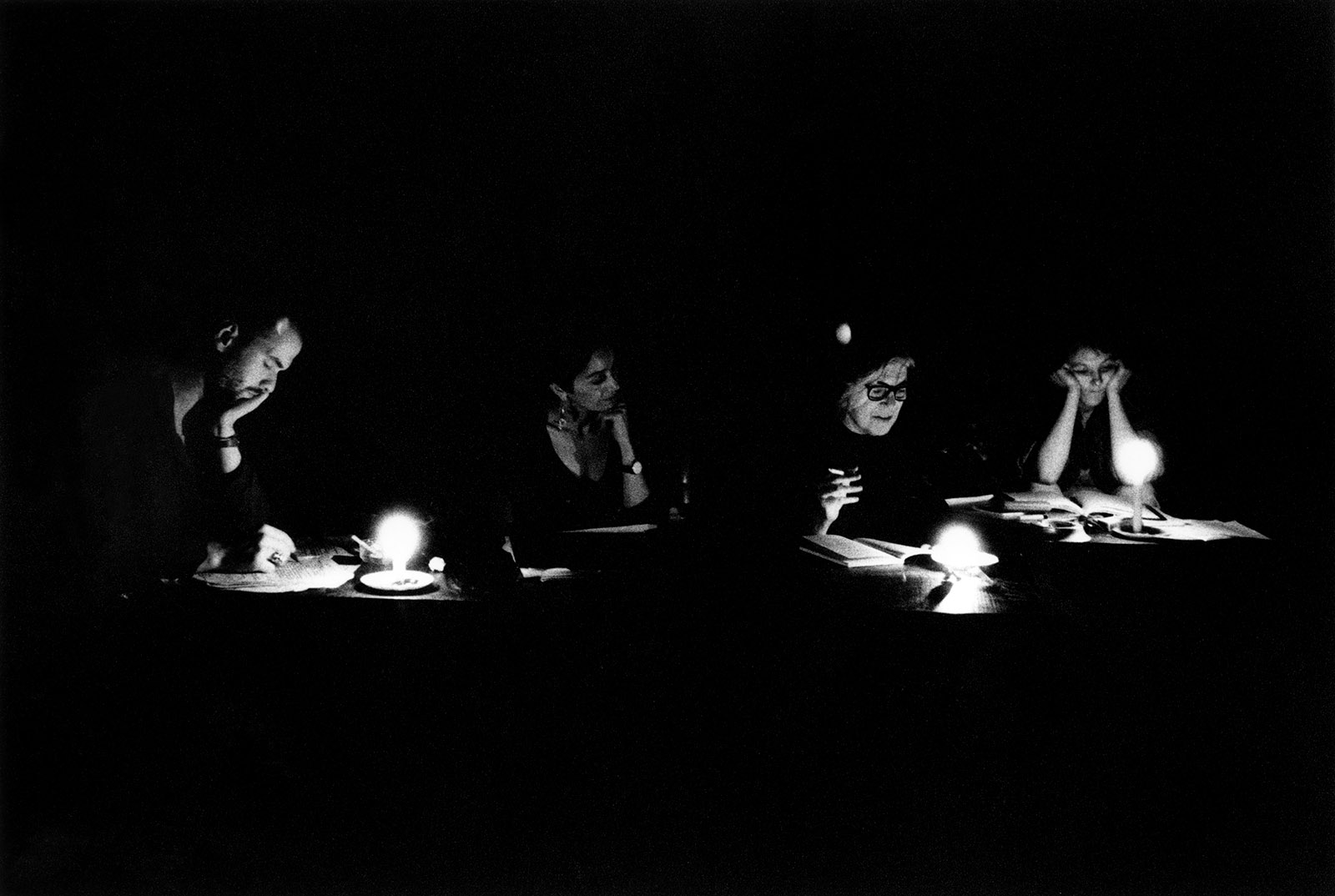

Susan returned to Sarajevo on July 19, 1993, to direct Waiting for Godot. This performance was produced without so much as electricity, and without costumes worthy of the name, and with a set made of nothing more than the plastic sheets the United Nations distributed to cover windows shot out by sniper fire. Yet this production became a cultural event in the highest sense of the term, an event that showed what modernist culture had been—and what, in extraordinary circumstances, it might yet be.

“Nowhere had the risk been so great, for what is involved this time, without ambiguity, is what is essential,” Alain Robbe-Grillet wrote in February 1953, less than a month after the debut of Godot. “Nowhere, moreover, have the means employed been so poor.” He was referring to Beckett’s own means: a set that consisted of a scrawny tree and a trash can; a strictly minimal language; a threadbare cast of beggars—one deprived of sight, another of speech—waiting for a salvation, a climax, that never comes.

In Paris, in 1953, these were artistic choices: metaphors. In Sarajevo, forty years later, they were daily reality. “They saw people being happy and suffering,” wrote the original production’s first reviewer, “and did not understand that they were watching their own lives.” This misunderstanding did not burden the Sarajevans. At the casting, Susan asked the actors whether there was a connection between their lives and Beckett’s piece. Admir Glamočak, who would be cast as the ironically named Lucky, answered:

I would act Lucky in such a way to portray Sarajevo, portray this city. Lucky is a victim. And Sarajevo was a victim. I was maybe ten kilos less than now, so I didn’t need any makeup and I just had to reveal a little bit of my body so you could see the bones and something that was supposed to be muscle. And everything that Lucky says that makes no sense was actually the voice of any person in Sarajevo.

Izudin Bajrović thought the choice of the play was obvious:

We really were waiting for someone to come and to free us from this evil. We thought that would be a humane act. A decent act. To free us from this suffering. But nobody came to help us. We waited in vain. We waited for someone to say: this doesn’t make sense, for these innocent people to be killed like this. We were waiting. We actually lived Waiting for Godot.

Susan stayed at the Holiday Inn, whose façade was painted a cheerful yellow and whose name associated it with middle-class vacations in unperturbed destinations. Now, a scant decade after being built for the 1984 Olympics, it found itself stranded at the end of a wide avenue officially called Zmaja od Bosne but notorious all over the world as Sniper Alley. This was the main road from the airport into the city center, and its many high-rise buildings stared straight out at the Serb positions in the nearby hills.

From the airport, one reached the Holiday Inn in a United Nations armored vehicle or, failing that, by car: to avoid getting shot, the trick was reclining the driver’s seat as flat as it would go, lying nearly supine, and speeding down the avenue as fast as possible. On the short distance between the airport and the Holiday Inn, people could be killed, and often were.

The hotel itself was a large rectangle surrounding a tall covered courtyard. The side facing the Serb positions had been shelled, but the far side was still largely safe. There, most foreign reporters were lodged. “One of the hotel staff said the place hadn’t been this full since the 1984 Winter Olympics,” Susan wrote. The staff went to great lengths to keep up appearances, but their smart uniforms became increasingly ragged, and they cooked whatever food they had on an open fire on the kitchen floor.

By siege standards, the Holiday Inn was a place of luxury: there was food, in the form of the starchy rolls served at breakfast. In the blockaded city, even these were something of a miracle, and nobody was quite sure how the staff managed to find them. One actor, Izudin Bajrović, remembered what this food meant to Susan’s starving cast:

For some reason, from somewhere, she would bring us rolls that she would gather at the breakfast table. And we ate those rolls and it was wonderful. Now, when you eat a sandwich at work, it’s not a big event. But at the time, when she brought those rolls, it was a very significant thing.

Ferida Duraković recalled Susan’s oblique ways of showing affection. “She was not a soft person,” she said. “You had to be very careful talking with her and being in her company.” Instead, she showed a more discreet solidarity:

At that time, she was smoking a lot and she was very nervous and she smoked like half a cigarette and then put it out in the ashtray. Suddenly, on the third or fourth day, I saw the actors waiting for her to put the butt out because it was half of a cigarette. After a break of fifteen minutes, they would go back to the ashtray. One morning she realized what she was doing and never did it again. She either smoked it to the end or she left a box of cigarettes just next to the ashtray, like she forgot her cigarettes. That was the way not to humiliate the actors.

Senada Kreso, an Information Ministry official responsible for helping foreign visitors, remembered another gesture, unforgettable because it meant being seen not as a pathetic victim but as a normal woman. Whereas many foreign visitors would come with food, Susan appeared with “a huge bottle of Chanel No. 5” as a gift for Senada. “That marked the beginning of my utmost admiration for the woman, not just the author.”

And Bajrović never forgot her kindness. “On August 18, my daughter’s first birthday, Susan came to the rehearsal with a watermelon. And when she found out that it’s my daughter’s birthday she gave me half of the entire watermelon. It was beyond the lottery. As if someone would give you now a brand-new Mercedes.” One of the most touching items in Sontag’s archives is a drawing of a green-and-white striped watermelon. Above it, in a childish hand: “Susan is our big water-melon!”

Throughout the hot, hungry summer of 1993, Sontag and her actors worked ten hours a day. The original Paris production—directed by a friend of Antonin Artaud’s, Roger Blin—had basic scenography, and so did the Sarajevo production: not because of an artistic choice, but because there was no alternative. They played by candlelight, of necessity.

The actors were filled with the import of their work. In no place but Sarajevo was such Artaudian drama possible, if Artaudian is taken to mean “the world of plague victims which Artaud invokes as the true subject of modern dramaturgy.” The production was acclaimed. Those who saw it never forgot it, said Ademir Kenović, a producer who, miraculously, continued making films throughout the war, including of Godot: “It was giving hope, and when something is strong, in war it is a hundred times stronger. When something is good, it’s a hundred times good. The psychological importance was huge.”

*

If the play made a powerful impact on those who saw it, it was also important for those who did not: those for whom Bosnia was a distant, inscrutable conflict. With what may have sounded like false modesty, Susan wrote that she was “surprised by the amount of attention from the international press that Godot was getting.” Only a few years before Internet use became universal, getting news out of the city presented an almost insurmountable challenge. Any means of communication that depended on electricity—radio, telephones, telegraphs, television—had almost entirely ceased to exist. The Bosnians were perfectly aware of the difficulties, and were not naïve about what would happen even if word did get out. But they were still hopeful, Izudin Bajrović said: “We were hoping that this project would open the eyes of the world. And they will see what is happening to us and they will react. And we were hoping that Susan Sontag was powerful enough to move things.”

When they learned how much publicity the production garnered, the besieged Sarajevans were thrilled. “The front page of TheWashington Post: ‘Waiting for Clinton,’ ‘Waiting for Intervention,’” said Pašović. “For us this was a very big victory—The New York Times and everybody wrote about it.” This was a recognition of the dignity that culture conferred. “We hoped that people in the outside world would learn about us,” said the poet Goran Simić. “People in the West had the impression that we were quite uncivilized people.”

Susan was frustrated by the indifference of her powerful friends, but two did show up and generated publicity of their own. In France, Nicole Stéphane had been involved for some months, making the rounds in France. Pierre Bergé, Yves Saint Laurent’s partner, was on holiday when the phone rang: “Susan is in Sarajevo and she wants to put on Waiting for Godot,” Nicole said, “but she needs money. Can something be done?” Bergé immediately agreed, and soon enough, Susan wrote:

Nicole surprised me by turning up in the besieged city (not an easy thing to do!) to direct herself, with only a cinematographer and a sound-man, a documentary centring on the production I was rehearsing with local actors in a bombed-out theatre of En attendant Godot… Nicole was, as usual, fearless and enthusiastic—just as she must have been as the adolescent volunteer in the Free French Forces in London who participated in the Liberation of Paris.

Miro Purivatra, who had asked David to bring Susan Sontag without suspecting that she was his mother, was in for yet another surprise. At the end of her first visit, Susan wondered if there was anything or anyone she could bring back, and he mentioned—again, without the foggiest notion of their connection—a famous photographer. “Maybe she could do some pictures here,” he said. “Then, maybe five months later, Susan Sontag is knocking on the door. ‘Hi, Miro. I have the guest you asked me to bring.’ She brought Annie Leibovitz.”

As soon as she arrived, Annie began making expressive photographs, including of the maternity ward at Koševo Hospital, where mothers were giving birth without anesthesia; and of the heroic journalists of the Oslobođenje newspaper, working to bring the news a stone’s throw from the front line. Perhaps Leibovitz’s most famous image was of a child’s toppled bicycle beside a stain—a half-circle, as in a Zen ensō painting—of blood. There was nothing airbrushed or removed about this kind of photography, as she remembered:

We chanced upon it as we were driving along. A mortar went off and three people were killed, including the boy on the bicycle. He was put in the back of our car and died on the way to hospital.

“Photographing is essentially an act of non-intervention,” Sontag had written in On Photography. Now, she saw how essential images were to the Bosnian cause. Published in Vanity Fair, they brought the war to the attention of millions who would not have read David Rieff in The Nation or John Burns in the Times. In the pages of the magazine, Annie’s work produced some odd conjunctions—“Here was suddenly Sarajevo next to Brad Pitt”—and in her own life. After photographing the murdered boy, she headed home: “I had to remember which side to shoot Barbra Streisand’s face from.”

*

Sontag would return to Bosnia seven more times before the Dayton Accords were signed at an Air Force base in Ohio in late 1995. The agreement ended the siege, but it partitioned Bosnia into the enclaves produced by “ethnic cleansing” and rendered the country economically stagnant and politically paralyzed. During the years of the siege, Susan’s life would be inextricable from Bosnia’s, and her heroic actions would continue entirely without the publicity Godot had brought.

On each trip, she brought rolls and rolls of deutsche marks, Bosnia’s unofficial currency, hidden inside her clothes, and distributed them to writers, actors, and humanitarian associations. She brought letters to a place that was cut off from the world and had no functioning post, and took them out when she left. She won the Montblanc de la Culture Arts Patronage Award in 1994 and dedicated the proceeds to Sarajevo. She tried to begin an elementary school for children unable to attend classes because of the war; she spoke ceaselessly for the Bosnian cause in Europe and the United States; she badgered friends in high places to help people escape Sarajevo.

When the Bosnian journalist Atka Kafedzić was refused a visa at the American embassy in Zagreb, Susan picked up the phone. “Give me half an hour and then go back to the embassy,” she ordered. The visa, needless to say, was granted, and eventually helped Atka’s entire family, fourteen people, begin new lives in New Zealand. Through Canadian PEN, Susan helped the poet Goran Simić, his wife, Amela, and their two children reach Canada.

In 1994, in the middle of the war, she began a novel called In America, which, when published in 2000, would be dedicated “To my friends in Sarajevo”—and “all that book was full of Sarajevo, full of energy from Sarajevo,” said Duraković. “She was alive here.”

But her newfound energy and purpose soured. Her indictment of the intellectuals who failed to rally to the side of Bosnia fermented into a self-righteousness that alienated the same people she was trying to recruit. Her activism was an inspiration, but she wielded it as an admonishing finger. This was unfortunate, because there was no arguing with the analysis she offered in 1995:

Individualism, and the cultivation of the self and private well-being—featuring, above all, the ideal of “health”—are the values to which intellectuals are most likely to subscribe. (“How can you spend so much time in a place where people smoke all the time?” someone here in New York asked my son, the writer David Rieff, of his frequent trips to Bosnia.) It’s too much to expect that the triumph of consumer capitalism would have left the intellectual class unmarked. In the era of shopping, it has to be harder for intellectuals, who are anything but marginal and impoverished, to identify with less fortunate others.

Like many who had witnessed terrible things, she found it hard to put her experiences out of mind. She found it hard, too, to be around people “who don’t want to know what you know, don’t want you to talk about the sufferings, bewilderment, terror, and humiliations of the inhabitants of the city you’ve just left,” she wrote in 1995. “You find that the only people you feel comfortable with are those who have been to Bosnia, too. Or to some other slaughter.”

That year, David published Slaughterhouse: Bosnia and the Failure of the West, an indictment of the international community. By then, his relations with Susan were “often strained.” From his perspective, Susan’s involvement in Bosnia was awkward. In Bosnia, David had discovered a mission. After meeting Bosnian refugees in Germany, he felt “the strongest sense of compulsion I have ever known as a writer… and boarded a flight to Zagreb.” Faced with the horror and injustice of the Bosnian war, he could hardly speak of anything else. Back in New York, he tried to convince others to come to Sarajevo: “I invited dozens of people, but the only person I persuaded was my own mother!”

She was aware of the uncomfortable situation her presence created. In public, she would defer to him. “I’m not going to write a book because I think in this family business there must be a division of labor—he writes the book,” she declared on her first visit to Sarajevo. David simply said: “It was not a promise she was able to keep.” Even before she came, he knew that if she got involved, “her role would inevitably eclipse mine.” But he had a clear choice to make. “Which was more important, the attention Sarajevo would derive from my mother taking up the Bosnian cause and working there, or my own ego and ambition? The answer was self-evident. Bosnia was infinitely more important than my wish not to be eclipsed by my mother.”

In public, David was careful to give Susan credit for what she accomplished in Sarajevo, but what was good for Bosnia was not necessarily good for their relationship. Even seven years after the end of the siege, when she was preparing her last book, Regarding the Pain of Others, she wrote a friend:

David does mind, very much, my doing this book. For him, it’s a continuation of the betrayal of “Waiting for Godot in Sarajevo,” which he asked me, in 1993, not to write, after I had promised it to the NYRB. Last night at Honmura An: “Couldn’t you leave me this one corner of the world as my subject?” That is, war. When I said, but it’s a sequel to On Photography, he replied, it’s about history, and about war, and you know nothing about history. You got all that from me, etc. You’re poaching on my territory.

I’m heartsick. But there’s nothing I can do now.

Godot did answer some of Sontag’s essential questions about the usefulness of modern art. It did not save the boy on the bike. Nor did it usher in military intervention. But she found a way to offer everything she had, following Vladimir’s exhortation in Act II:

Let us do something, while we have the chance! It is not every day that we are needed. Not indeed that we personally are needed. Others would meet the case equally well, if not better. To all mankind they were addressed, those cries for help still ringing in our ears! But at this place, at this moment of time, all mankind is us, whether we like it or not. Let us make the most of it, before it is too late! Let us represent worthily for once the foul brood to which a cruel fate consigned us!

If a condition of the modern artist—of the modern person—is an awareness that Godot will not be turning up, that does not mean that that person is not needed, cannot make some difference. Sontag’s determination to make that difference made her exceptional, and after her death, the plaza in front of Bosnia’s National Theater was named Susan Sontag Square. Admir Glamočak said:

Susan Sontag was made an honorary citizen of Sarajevo, the highest award the city gives: I don’t have that award. I don’t have my own square in front of the theater. Not only me, but none of the actors. Old actors get some little street in the suburbs once they’re dead. But I always think: if it’s Susan Sontag, she deserves that damn square.

This essay is adapted from Sontag: Her Life and Work, by Benjamin Moser, published by Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins, on September 17.