The Covid-19 quarantine, which has in many other ways decimated my concentration, has revived my collage industry. I started making collages around age thirteen, in part out of frustration at my poor drawing skills and in part because of the lure of unpredictable found objects. The practice reached its peak in my twenties, when I made fliers for bands and had a hand in a zine or two. Then the scene changed, the bands broke up, and I no longer had an audience or a purpose. So I quit making visual work for nearly forty years. But the flame never entirely went out, as proven by the fact that I lugged my materials—piles of magazines, accordion folders full of clippings—from apartment to apartment and house to house, at least nine times.

What brought me back to action a few years ago was Instagram, which seems to include more people I know IRL than any other social medium—nearly all the most visually oriented of my friends. Instagram became a wall on which I could slap up my latest collage for a bit, before it got covered over by new stuff by others. I’m a performer; I have to work to some semblance of a crowd, however small. Getting a reaction stimulated me to keep trying to top the previous thing I put up. After about a year, though, even that flare-up subsided; my hobby ceded to more pressing matters. But then the quarantine came along. All of a sudden I was in need of a form of expression that would bypass the usual cognitive pathways. I had no reason not to make collages, and seemingly all the time in the world, since every day had become about a month long.

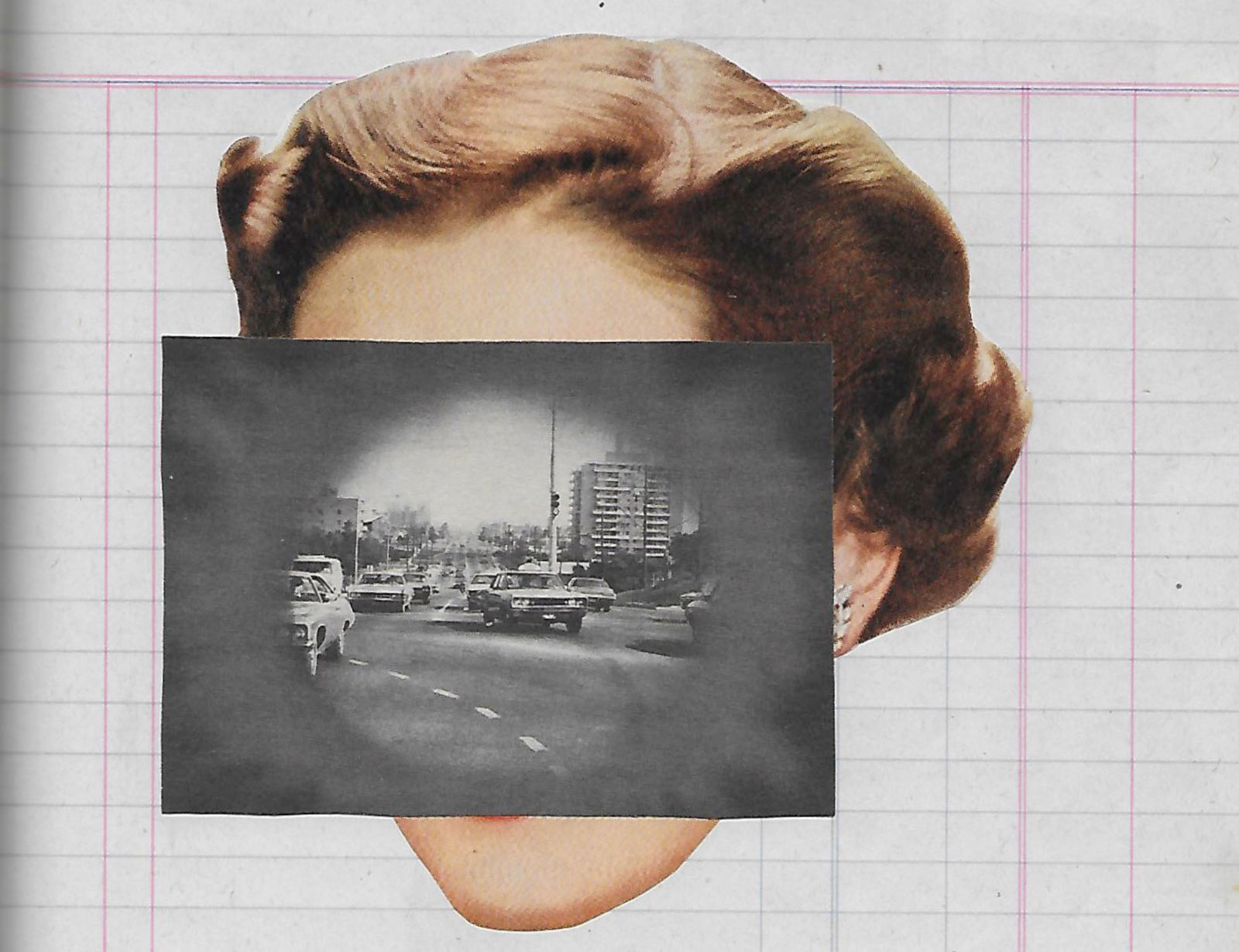

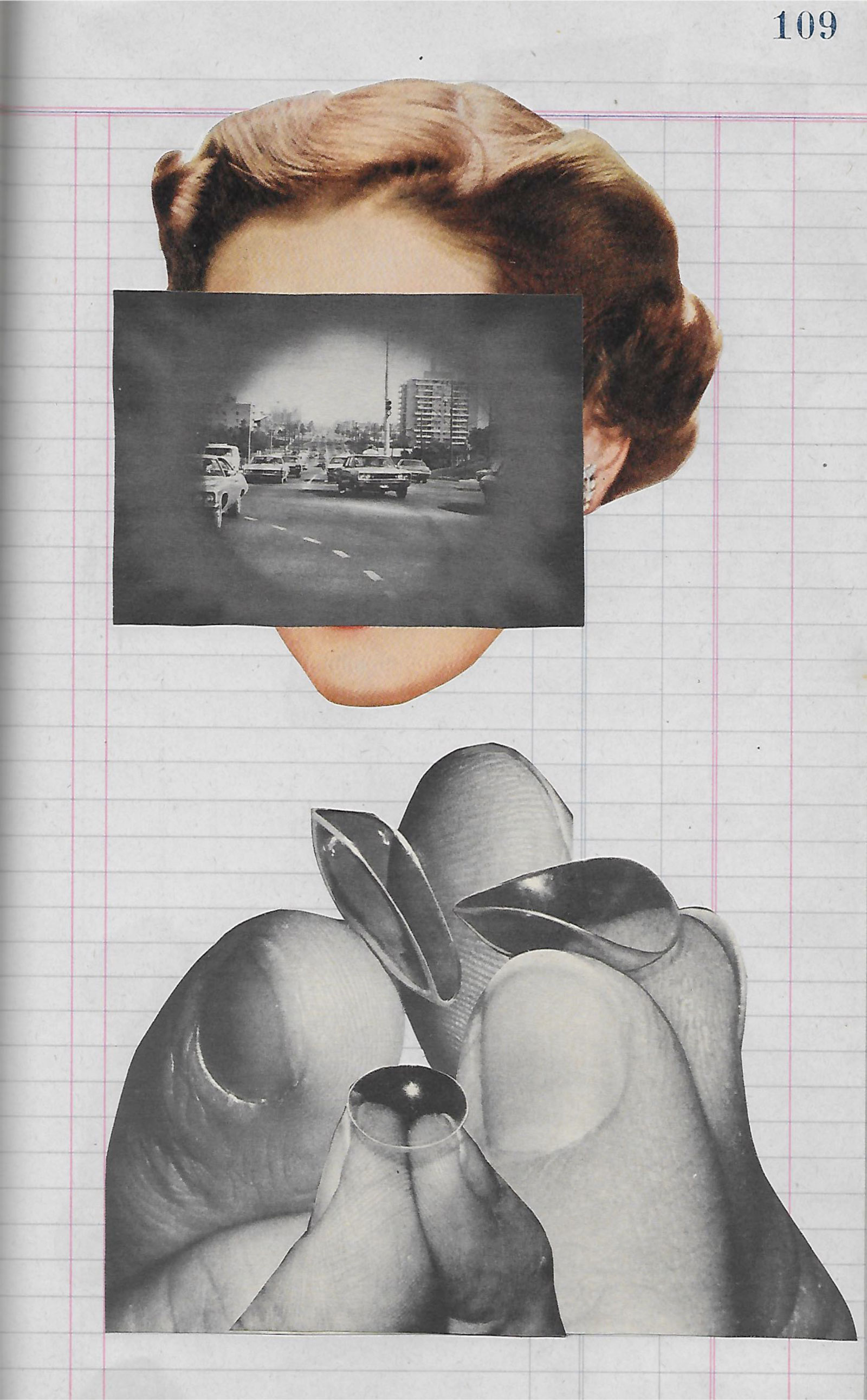

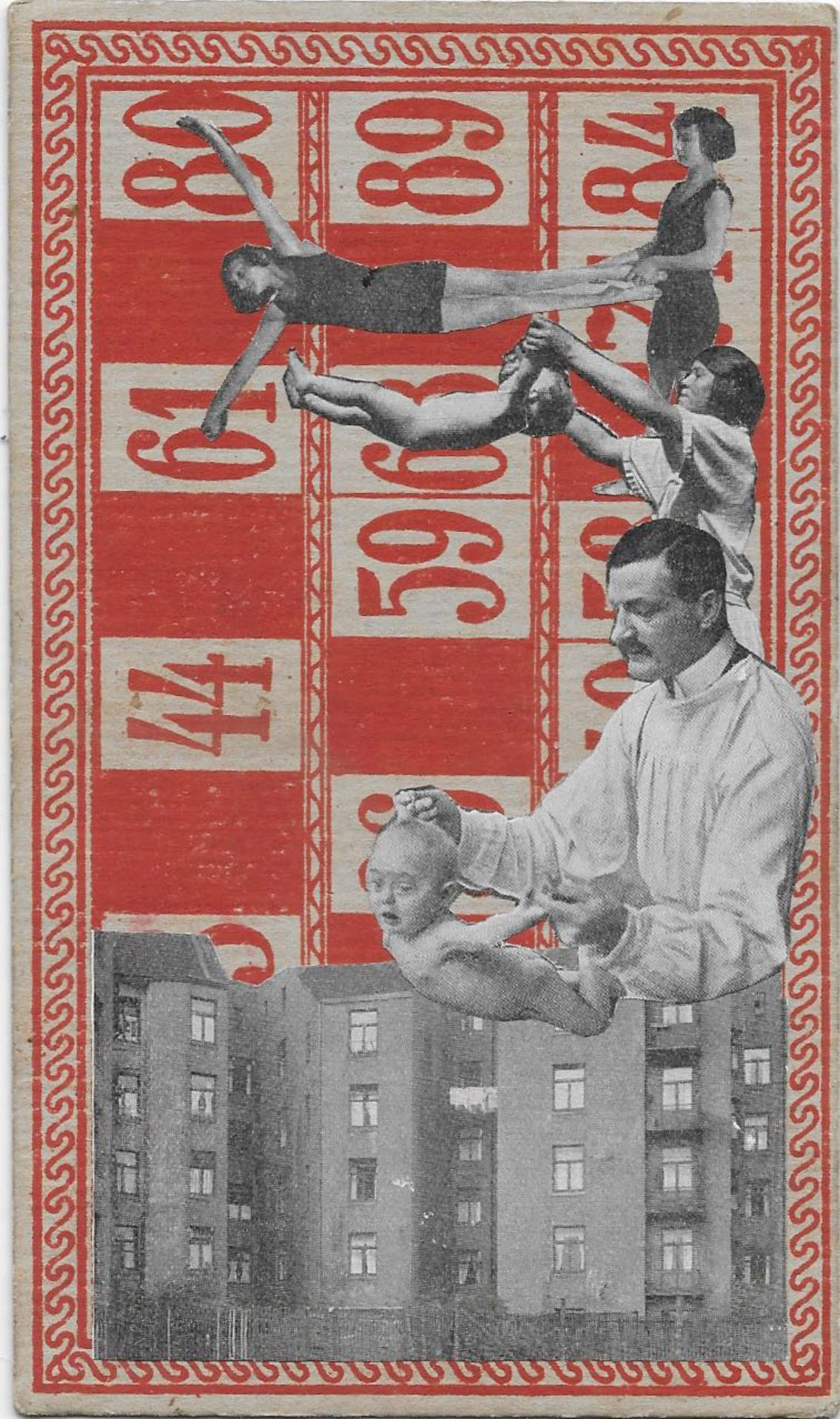

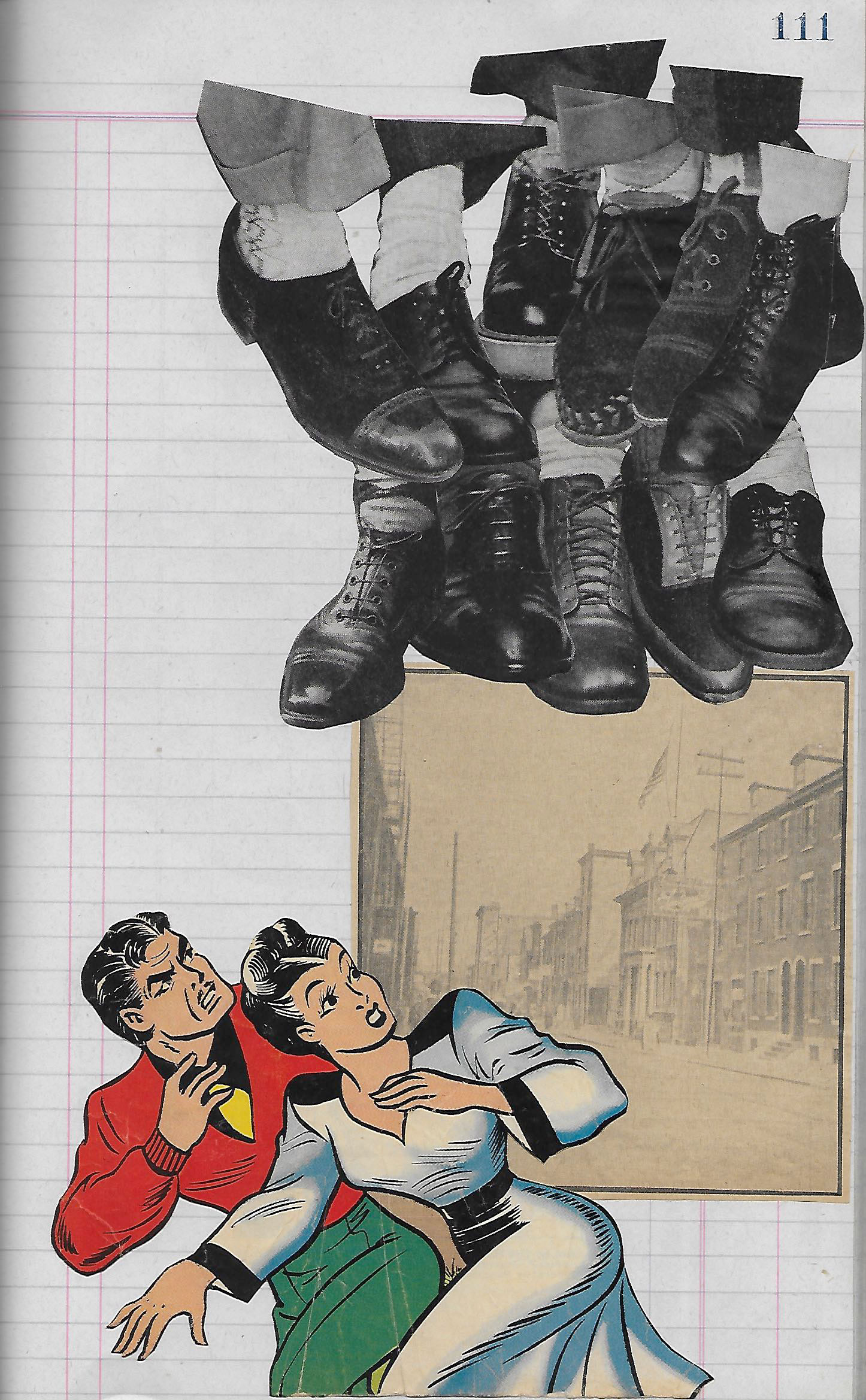

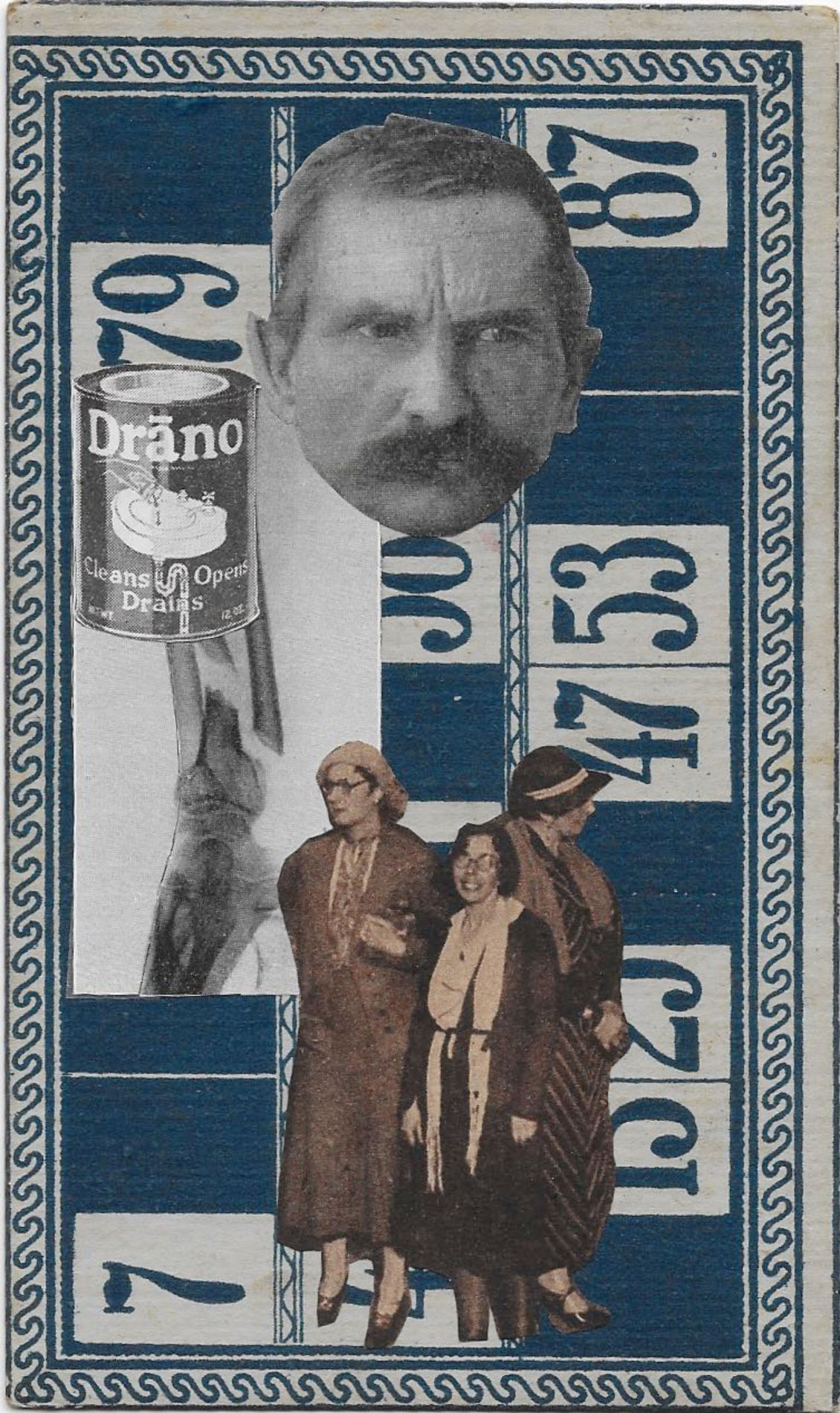

So I’ve been making collages in consecutive series determined by physical constraint: a ledger, a stenographer’s notebook, mounted industrial photographs, a deck of lotto cards. I have a vast trove of imagery to draw upon: the disbound and damaged books I collected while working at the Strand Bookstore after college, the New York Post headlines I hoarded in those same years, the bag of half-shredded movie posters I bought from a street peddler in the Nineties, the wildly random ephemera—a German medical textbook from the Twenties, crudely illustrated Spanish pamphlets from the Thirties, movie-star magazines from the Forties—that until recently I was able to glean from the book-exchange table at my local supermarket. Collage is a scavenger’s art: it forms the dead matter of the past into combinations that could only occur in the present; it builds a future from ruins.

Collage in many ways has been the dominant form of the late modern era, affecting such areas as music (sampling) and architecture (the incorporation of preexisting elements into new constructions). But for all of its links to other forms of art, the cut-paper collage is a specific tradition all its own, which may now seem to be narrowed by the extinction of most paper ephemera, although it always had a retrospective quality. It is usually dated back to Dada, but is actually rather older (I have on my wall a collage that looks very mid-Twenties Surrealist—sea creatures and mythological characters disporting themselves amid oversized flowers against a field of stars—but was made by an English clergyman in 1864). Collage effortlessly vaporizes the line between high and low; it has been practiced simultaneously by avant-gardists and folk artists during its entire history. It has its own schools of thought and lines of transmission. I’m particularly alert to the currents that run from Rodchenko and Lissitzky and Moholy-Nagy, and from Max Ernst and Hannah Hoch and Kurt Schwitters, to Jess and Bruce Conner and Joe Brainard and my contemporary Richard McGuire. In making my collages I feel as if I’m engaging in a conversation that runs back and forth across the decades.

Much like writing, collage-making is a series of narrowing decisions. The ground can be big or small, square or oblong, blank or patterned—and the choice restricts the pool of possible figures, by color and size and grain. Do you want an implied horizon, or do you want to ignore depth altogether? Do you want to stick to images from one period, or promiscuously mix them up? You have two possible dominant modes, the narrative and the visually formal, of which the latter is harder—which way do you want to bend? Personally, I like to work at their point of intersection, where both things are present but neither dominates. I enjoy the challenge of making something that can be consumed by the eyes with no thought involved, and at the same time introduce a thought that lies just on the edge of meaning, preserving maximum ambiguity. Collage-making suits the moment; it is a meditative practice that requires the regular exercise of fine motor skills. It imposes calm.

Advertisement

This is part of “My Quarantine,” a continuing NYR Daily series in which our contributors share how they’re spending their time while social distancing.