“If she stops breathing, it’s just because she’s forgotten that it’s something she’s supposed to do,” the pregnant nurse told them, on their very last day in the NICU. “When that happens, just slap her cheeks very softly. Just give her a little pinch on the fingernail.” […] It spoke of something deep in human beings, how hard she had to pinch herself when she started thinking of it all as a metaphor.

—Patricia Lockwood, No One Is Talking About This

Since working as a psychoanalyst in palliative care in the early months of the pandemic, I have had breathing on my mind. I watched coronavirus patients struggling to breathe, breathing by machine, learning to breathe again off the machine, if they survived the machine. My son was asthmatic as a child, as was I; sometimes I believe our asthma was psychosomatic. Patients, on occasion, have had panic attacks in my office; I’ve only once considered calling an ambulance. I’ve worked with breath through pranayama in yoga practice, which calms the nervous system, lowers the rate of respiration, miraculously reducing “dead space” in the lungs. Shallow breath is breathing into dead space—which is not a metaphor.

I’ve also picked up some strange facts along the way: an American pilot named Dr. Forrest Bird, who had worked on aeronautical oxygen regulation for flying at high altitudes during World War II, was the first person to make a reliable, low-cost, mass-produced ventilator in 1958. He modeled his machine on the way air moves across the wings of a plane: airfoils, he realized, were like alveoli. His device made iron lungs obsolete; and he eventually created the BabyBird, which radically reduced the mortality rate of infants born prematurely. If the story wasn’t already uncanny, Dr. Bird’s inventions failed to prevent the deaths either of his first wife, who died of lung damage after severe bronchitis, or of his third wife, who died in a plane crash, but his BabyBird did save his stepdaughter, who was born a month premature. She now runs the museum that bears his name—the Bird Aviation Museum and Invention Center in Hayden, Idaho.

Helping us to breathe, holding our breath, but also taking our breath away: In this long year, have we not surreptitiously faced an entire human history embodied in breathing? We must not forget what the coronavirus—breath, masks, contagion, and death—has stirred into consciousness. The video of George Floyd being suffocated by a police officer went viral and reignited the struggle for civil rights, forcing a reconsideration of the violent history of racism in this country, while the cataclysmic forest fires in Australia before the pandemic and in California during it seem to confirm the climate catastrophes to come. The air will become more and more infected, toxic, while asphyxiating forms of oppression have drawn us into dead space. Again, not a metaphor.

Neither is this: the most significant advances in medical ventilation have taken place in the last twenty years when computers could address the problems caused by machines forcing air into delicate lungs, often injuring them in the process. It took a long time for doctors and scientists to understand that you cannot just force someone to breathe. The new machines sense the diaphragm’s spasms that signal the desire to breathe, and the breath’s timing and volume, and can match both to a tee. This mimicry of the human body by machines could be a saving grace, especially in the face of an inability to modulate human interventions on life more generally. But just as the Internet has played a large part in the erosion of democracy, technology is always a double-edged sword, contributing to the destruction of the planet, no less of ourselves, that it is then called upon to save. This same digital technology brought the murder of George Floyd—and with him, so many others—finally to our attention. Dr. Bird is not a metaphor for Icarus, which is not a metaphor either.

*

Does psychoanalysis have anything specific to say about breathing? It is striking—even though it should have been obvious—that most of the speculation of early psychoanalysts about “psychosomatic” asthma, or anxiety (the acute form of which always involves panic attacks), or even autoerotic forms of constricting breath, points to birth. And birth is seen as either the earliest source of trauma, or a trauma we return to because of others, because of life.

Sigmund Freud had a contentious debate with his colleague Otto Rank, whose theory of “birth trauma” Freud saw as committing Oedipal heresy (which, for Freud, was of course the root of all neurosis). Rank resigned from the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society in protest and left for Paris in 1926. Seemingly victorious, Freud nonetheless continued to wrestle with Rank and the matter of birth, in absentia. Freud used the word Hilflosigkeit to describe infancy and childhood—the translation is “helplessness,” the inability to help oneself, or give help to another. “Impotence” is another possible translation, in which we should hear powerlessness, defenselessness, and poverty. Regardless of whether the trauma is seen as Oedipal or originating at birth, the psychoanalytic point seems to be that what is intolerable is helplessness, prematurity, being born:

Advertisement

The biological factor is the long period of time during which the young of the human species is in a condition of helplessness and dependence. Its intra-uterine existence seems to be short in comparison with that of most animals, and it is sent into the world in a less finished state… The biological factor, then, establishes the earliest situations of danger and creates the need to be loved which will accompany the child through the rest of its life.

Freud worries that spoiling a child will make fear of the loss of love too great, placed above all other dangers, especially real dangers, encouraging the child to remain in a state of childhood, neurotically seeking protection and reassurance. Anything that overwhelms the mind, whether from an internal or external source, sends us tumbling back into a state of utter helplessness, maybe even back to birth, gasping for breath.

Freud theorized helplessness again and again throughout his life. He also worried and complained about it bitterly in his letters: “I have always hated helplessness and penury most of all, and I am afraid we are now approaching both.” One has to get out of the state of helplessness, but the cost of “adult” life can be an amnesia for infancy and that portion of childhood when we were unable to help, when we lived in a universal poverty. Should feelings of helplessness return, they can immediately induce anxiety or rage, a defensive bid for omnipotence as an exit strategy. Enter tyranny, racism, child abuse, disregard for inequality, climate denial…but I’m getting ahead of myself.

As one of the latest acquisitions in human evolutionary development (roughly 360 million years ago), the lungs are one of the last organs to develop in utero, making them especially vulnerable; they are also, by some measures, the largest organ in the body (next to the skin) if every surface were unfolded and laid out. Birth trauma, in this regard, is not only separation from the mother, but also having to breathe, having to take something foreign into the body. We are not only dependent on our caregivers, we are also dependent on air. Separation is a fact, but it is also a fragile process, and as with breathing, there are vulnerabilities, forms of resistance, ways of co-opting what seems, at least on the surface, as though it should just happen.

What kind of evolutionary trick is this? Well, the trick is also key to the development of language. Not only breathing, but eating, and, more importantly, speaking (and singing) make use of the mouth, the nasal passages, the airways, and diaphragmatic structure of the lungs. Very early, the baby has to find a new kind of life rhythm to that in utero, centering on sucking, breathing, and cooing as an oral counterpart to what is taken in from the world through looking, smelling, and hearing. This sensorium swaths the infant in its first months of life.

If psychoanalysis is about speaking—say anything, say everything—breathing acts like a hidden navel, psychoanalysis’s ground zero, the site of our separation from the mother, where we lose our words, maybe even a capacity for self-representation. Breathing is the space where extreme anxiety, the mute body, and the scars of being born rear their head. I’m trying to refrain from using the word crown, especially because of its resonance with corona, but the possibility of choosing one’s words carefully is precisely the point. Language and the act of speaking are crucial in this story. Being born seems to need to happen, at the very least, twice.

For many years, I had heard of a mythical creature, a psychoanalyst who had a position in a neonatal intensive care unit at a hospital in Paris. This analyst would whisper to the babies their history, the conditions of their coming to be born, and who their parents were, in an effort to speak them into life. Why some babies survive and not others, why some succumb to sudden infant death syndrome or failure to thrive, was more mysterious and complicated than medical pathology could account for. She decided it was a psychoanalytic problem.

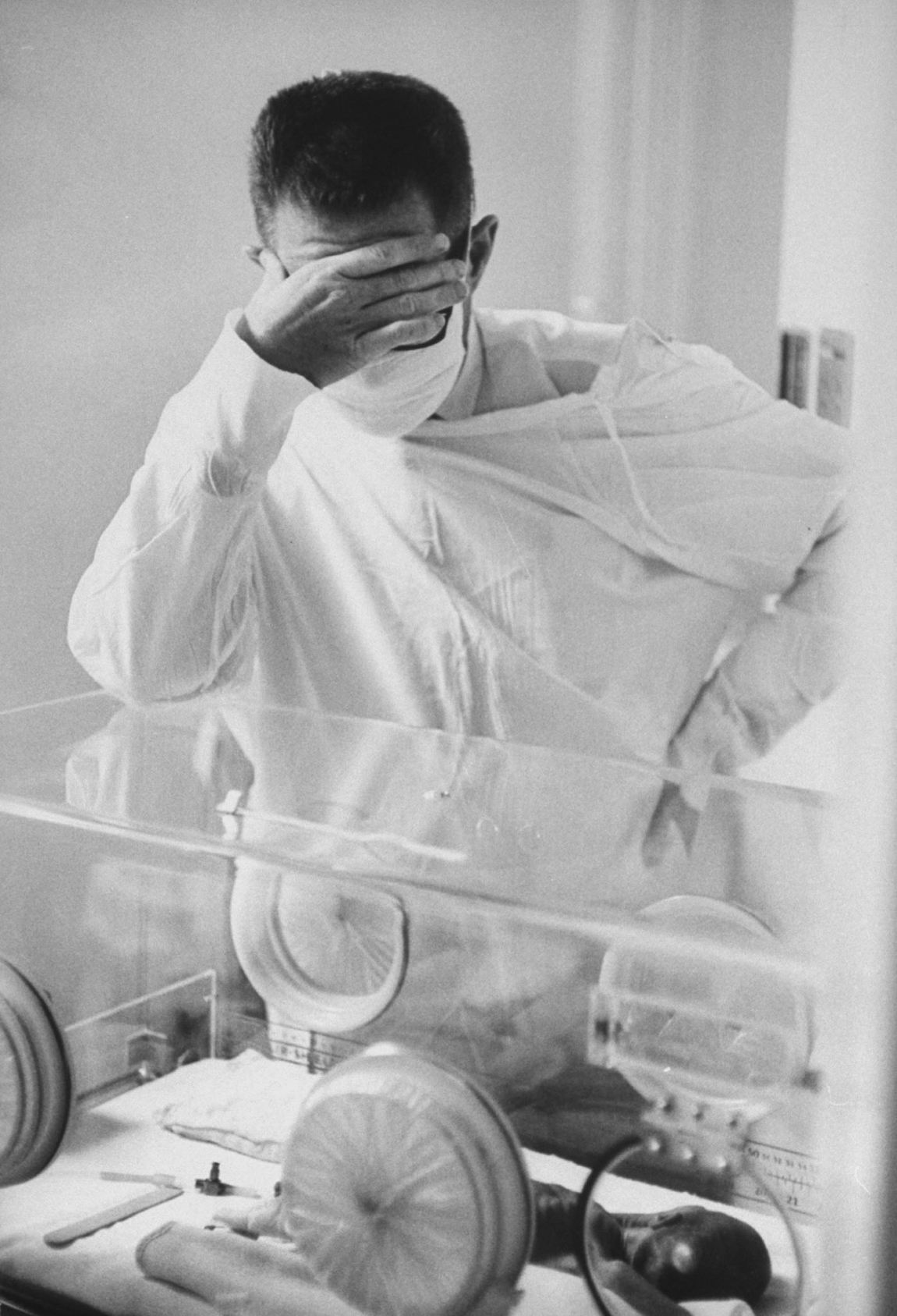

In her book Premature Birth: The Baby, the Doctor and the Psychoanalyst (2015), Catherine Vanier points out that even as we began to be able to save premature infants, it took time for us to see them as having been born and needing to be treated accordingly. Doctors, until about thirty years ago, thought that premature infants didn’t feel pain; so they operated without anesthesia. These infants were enclosed in boxes and hooked up to machines and feeding tubes, devoid of human contact. This made weaning the infants from these devices all the more difficult. Who was being protected in this scenario?

Advertisement

Protocols began to change fifteen years ago, recognizing the importance of contact time between newborns and parents, though the explanations for the new procedures were purely behavioral and stopped short of addressing the infant as a subject, even if a nascent one. Vanier saw her work as a co-resuscitation, bringing the infant into life with the doctors, as well as bringing the parents to life for the child. She saw that parents, terrified that their infants might die at any moment, often wanted to abandon them to the care of doctors—who couldn’t themselves understand the implications of their power to keep alive, or not, the tiny infants. Someone needed to gather up these forces.

The critical point was often taking the infant off the ventilator: Would they take up the task of breathing, or not? One story, in particular, from Vanier fascinated me. Together with the NICU staff, the care team saw that one of the infants could be taken off the ventilator if the ventilator was left running so its sound was audible from the baby’s incubator. If the sound stopped, the infant stopped breathing. It was as if the respiratory drive could exist if minimally propped up by the rhythmic noise of the whirring machine.

What could wean her off of this, then? Vanier speculated that it could be the voice of the mother—and encouraged her to speak to her child often, showing the mother that the baby reacted strongly to the sound of her mother’s voice. It was also important, Vanier insisted, that the mother speak the truth—her worries, her anger, her concern, her love, all of it; empty speech would not do. The infant was eventually able to make this vital transfer from one object to another—from machine to mother—which was the difference between life and death.

Reading about Vanier’s work, I had to wrestle with a perverse cynicism that wanted to deny any importance to what she was articulating, as if it was just a lot of hocus pocus in the vein of…a touching story, but not real. This was a strange sentiment since I, too, am a psychoanalyst, and I have experienced the quasi-magical power of speaking, simply speaking, to affect the body. I also believe in speaking in the direction of truth as best one can.

Why would I want to deny something so fundamental? Was it resistance to touching this primordial point, laying open this scene of utter helplessness, which also demonstrated what must be offered there, and too often isn’t—or wouldn’t be—in the climate in which we currently live? Was it simply pure hatred of impotence? We may be born, but we are not all carried to term.

*

“It would be interesting to discuss the relative importance of the control of the bronchus as an organ,” wrote the pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott in 1941, in his paper “The Observation of Infants in a Set Situation.” At the Paddington Green Children’s Hospital, where he worked for twenty years, Winnicott created a method for observing caregivers and their babies. In that essay, he turns to the case of a seven-month-old who had been suffering from bouts of asthma, as did her mother as a child and during pregnancy. He was able to observe one such attack, and wrote of it:

The breathing out might have been felt by the baby to be dangerous if linked to a dangerous idea—for instance, an idea of reaching in to take.… It will be seen that the notion of a dangerous breath or of a dangerous breathing or of a dangerous breathing organ leads us once more to the infant’s fantasies.

Asthma, Winnicott says, is an involuntary control of expiration, a difficulty in letting go of one’s breath, or, from another angle, an excessive holding of breath. It can only be a fantasy of imagined repercussions, he posits, that would stop the baby from surrendering to a natural impulse. When natural inclinations are brought to a halt unnecessarily, symptoms erupt. Fortunately, this kind of inhibition in infants, in contrast to that in adults, can be reversed quite quickly by allowing the wish to carry on in its merry way. Babies are so new to the world; miraculously open to help.

Meeting the infant’s desire for help is what was a “good-enough,” in Winnicott’s words, “facilitating environment.” The way he sees the secure infant in his observational situation is fascinating. Three temporal moments transpire, which all have a logical, rhythmic structure, one that almost feels likes breathing. The composition is uncannily close to the three temporalities that the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan described, using the prisoner’s dilemma from game theory. I had previously used these markers to describe the unfolding pandemic: the instant of the glance, the time for understanding, and the moment for concluding.

To begin, the mother—in Winnicott’s essay, it is only mothers, characteristically of the time—enters and walks across a large room with her baby to Winnicott, who is sitting at a table. She is asked to sit catty-corner across the table from him. The scene of arrival is important so that the mother, child, and doctor have a chance to see one another and make visual contact before settling in. Winnicott then places a shiny, right-angled tongue depressor (which he calls a spatula) on the table. He tells the mother to sit in such a way that if the baby should wish to take the object, it can—but she is instructed not to help or interfere and to contribute as little as possible to the situation. The classical setting with couch, patient, speech, and analyst is here transformed into mother, baby, spatula, and doctor.

During what Winnicott calls stage one, the baby puts its hand out to the spatula, but realizes that the situation requires more thought. The baby grows still but not necessarily rigid—looking at the doctor or its mother with big eyes, or withdrawing from the situation and burying itself in the mother’s chest. No reassurance is given, since what is crucial is the spontaneous and gradual return of the child’s interest in the seductive object. Like the moment of the child’s glance, what dominates is a question about what this object, and this strange other, means for the baby. Who are you? Who am I? What is possible here?

This leads to the next stage, in which the hesitation conflicts with desire. The baby must become “brave enough to let his feelings develop,” which will change the encounter quickly, an alteration evident first in the child’s body. The baby’s mouth becomes “flabby,” its tongue “thick and soft,” and it might even begin drooling. Stillness then gives way to movement with a decisive action. With the spatula finally in hand, the infant displays a sense of confidence, even power, giving rise to play—putting the spatula in its mouth, joyfully banging it on the table, offering it to its mother’s mouth, or the doctor’s, pretending to feed them like a baby. “See” with your mouth, test the world with this, your first device.

One might imagine that this would be the final stage, and Winnicott himself says he thought so, too—that it took him some time to see there is an important final move. In stage three, the infant drops the spatula, perhaps by accident, but then plays with getting rid of it, which is thoroughly enjoyed. The infant may want to get down and mouth the object again on the floor, but will eventually lose interest in the spatula, leave it behind, and turn its attention to the wider room. Leaving the scene of the object is a second act of bravery.

The infant must feel that what is left can be returned to, and yet this can never be guaranteed. If the moment for concluding an encounter is always the negotiation of an exit, with the baby this comes after the triumphant exploration of its satisfaction, whereas, in the prisoner’s dilemma, it is about coming face-to-face with the inability to completely understand, or square, the loss, implied in leaving, but leaving nonetheless. Perhaps both types of the third stage speak to a limit that encourages a renunciation of what is found, to risk giving it up in order to look farther afield and step into an unknown future.

So what happened with the asthmatic seven-month-old? Paralyzed in the time of hesitation, the baby may have felt too greedy, too wary of retribution, too great a threat of loss, or without hope for more satisfaction. Basic anxieties must be run through and remodeled. This isn’t about the perfect protection of parents that may, in fact, make one more neurotic; rather, the complexity of the infant’s feelings is held by a good-enough caretaker until they can unfold in their own time, becoming more distinct desires. Could we say that the asthmatic infant is thrown back into its being, especially that of being a body, inhibited in the face of the object that they cannot take, play with, or feel untrammeled pleasure toward? Is the hesitation Hamlet-like, a predicament of being caught in the oscillation between to be and not to be?

The infant at stage two, on the other hand, creates an object, is seduced, plays at being seductive, turning subject into object, passive into active. In the game of feeding mother just as one is fed, the infant has a self-representation on the outside to test, perhaps a little like curating one’s image on Instagram and looking to see how many people like it. Only after the glittering object is ready-at-hand can the infant explore not-having, losing it, dispensing with it—a breach that opens onto the wider world. This makes me think of when my son was able to give up an obsessive concern with the integrity of his Lego figures, which were finally, to my great relief, exploded all over the room.

So we have three distinct temporal waves—being, having, not-having. Beginning and end meet; being is close to not-having, but it is modified by the step of having-had. One might even say that being is finally transformed through an act of mourning, of loving and losing, rather than being a place of retreat, of losing oneself entirely, or sticking with the repetitive power of having. Traversing these three moments, Winnicott says, is a preparation for the advent of language. Born thrice?

*

Writing was invented only because of an absence, averred Freud, just as the child who cries out at night is not afraid of the dark but is longing for its loved one. None of what I’ve written here is meant as metaphor, which is the particular dispensation of writing about infants. Pandemic life is a little like hovering around the table with Dr. Winnicott, circa stage one. The privileged, we could say, have been well looked after. Having a safe, bountiful environment during a global catastrophe means the pandemic could perhaps provide a miraculous renegotiation of not-having; certainly, not-having much of a world while having so much. But the bodiless, objectless, shapeless confusion of lockdown’s turn to life online isn’t much of an object to offer as a way out.

In the beginning, we compensated for our enforced virtual life by making the phone calls we had become wary of in a text-driven phobia of voices. Now, after enduring winter’s second wave, it feels rather as if we’ve run out of things to say, even if we are lucky to work, work, and work some more. Doesn’t it all feel practically around the clock?

I love the moment when infants make language their object, something that they can always carry with them. The joy of babble, stretching syllables, the pure singsong of speech. It is, of course, a step beyond mere breathing and surviving. It is not a line, but a circle, and the two ends meet, since the voice leans on breath and is as immaterial as air. This is not the hard, glossy reality of either the tongue depressor—coincidentally, both Winnicott’s favored toy and the tool used by doctors during intubation—or the tens of thousands of ventilators unnecessarily hoarded in the panic early on during the pandemic; rather, it is an elusive object that is easily forgotten—the once-lived reality of safely breathing the same air and speaking to one another unobstructed.

More important, however, is the pandemic experience lived solely at the level of being—not merely in the sense of being sick, without breath, bereft, or confused about what is possible, what there is to take or to have, or being without a future. I mean in the sense of being forced to take stock of those whom we have treated as objects, whom we have reduced to mere bodies, whom we have told they have no right to have, or whom we have never properly mourned. It is hard to inhabit an environment that, for some, has never allowed them to fully be born, to come into life, while others have enjoyed it in abundance.

While the trouble with breathing is so close to the surface of our experience, we might want to say that it’s merely a consequence of the coronavirus, an accidental event existentially felt. But don’t you feel impelled to go a little further? To see this time as a return of the repressed, signaled by the cutting off of breath? The too loud and too visceral cry for help? One need not be a psychoanalyst to make this leap—for how can the question of death not bring us back to the scene of being born, that each of us has forgotten, but must remember somewhere. We forgot what we were supposed to do: breathe in…breathe out…sing to me.