John Edgar Wideman has been my most important teacher, though I didn’t attend any of his courses. I still think of the time I first read the stories in Wideman’s Damballah, already well into my undergraduate studies, as the moment my education really began. As the child of Congolese immigrants, I was entangled in multiple lines of descent and responsibility. Like so many other young Black Americans coming of age in the late 1980s and early 1990s, I was trying to create an identity. But I also felt a need to extend the political advances achieved by previous generations’ liberation movements throughout the African diaspora.

None of this was easy to narrate to myself or others. Because my literary education began very traditionally—Chaucer, Shakespeare, Keats, Austen, Dickens, and Woolf—I didn’t have models for creating stories about my in-betweenness. Luckily, other parts of my formal (and informal, often subterranean) training included listening to, reading, and watching Achebe and A Tribe Called Quest; Gwendolyn Brooks and James Baldwin; Morrison and Makeba; Bird and Dizzy; Richard Wright and Frantz Fanon; Spike Lee and Public Enemy; Miles and Coltrane; Kincaid and Walcott; Ellington and Monk; Wole Soyinka and August Wilson. They offered me an abundance of beauty, feeling, and intelligence. But it wasn’t until I read Damballah—electric with Wideman’s modernist experimentation and his orchestra of voices—that I began, as Ralph Ellison might have put it, to create the uncreated features of my own face.

During a period in my early life of rudderless wandering, intellectual adjustment, and growing psychological awareness, Wideman’s first story collection guided me as no other artwork could. Even three decades on, the collection’s title story, “Damballah,” continues to shape my understanding of how the strongest Afro-diasporic traditions maintain and renew themselves. In that story, Wideman flips the American slave narrative on its head: rather than describing his characters bound by their subjugation, Wideman draws our attention to Orion, a fish-gathering griot, whose daily ritual summons Damballah Wedo, the primordial father in the Vodou pantheon who both signals the ancient past and assures the future.

Parsing “Damballah” as a student that first time, I noticed, just as the young, unnamed slave boy does, that Orion embodies his freedom defiantly. Proudly African, Orion designates the crossroads with the Kongo sign, calls for Damballah’s guidance, and creates an African/American tradition. When the boy catches the spirit and learns to make the sign and speak the word, he’s also learning that he might shape a powerful identity from this meditative ritual. When the plantation’s master and overseer find out that Orion has maintained his Yoruba-based religious practices, the penalty is deadly: they sever Orion’s head from his body. At the story’s end, the boy retrieves Orion’s head, carrying it to the ceremonial site. Listening to Orion’s stories once again, he blesses the head and sets it adrift to the waiting fish. In that act, the boy takes up the ritual as if born to it, as if born from Orion’s head—the narrative tradition passing cyclically, mouth to mouth, like life-giving resuscitation.

Damballah, Hiding Place, and Sent for You Yesterday form The Homewood Trilogy. The overarching story those works describe begins with Sybela Owens, a slave who ran to freedom with Charlie Bell, the slave master’s son. The couple established Homewood, one of Pittsburgh’s first predominantly Black American neighborhoods, during the 1850s. These two characters sit atop the “Begat Chart” in Damballah; Wideman molded these characters from family lore about his own ancestors. Though Wideman uses some Homewood street names in his first novel, A Glance Away, the district goes unnamed as such. Damballah offers readers the first entrée to Homewood specifically.

The stories from Damballah lead readers into the lives of the French and Lawson families. The character John “Doot” Lawson is a writer-translator, if you will; he’s collected anecdotes from his family and transposed them into literary fiction. Lawson lives with his own family far away from Pittsburgh, hoping that distance might create opportunities for establishing his writing life free from family disarray and trauma. However, over the course of the trilogy, Lawson discovers that writing about the lives of his maternal grandparents and extended family members, turning their experiences into fiction, allows him the possibility of discovery through characterization and reveals that the roots of his own aesthetic lie in the fertile modes of oral storytelling his family members have crafted. In Damballah, Lawson’s stories help him find his way back to Homewood.

Wideman invites readers to sit alongside him, amid these stories, listening and reading in multiple directions simultaneously. Wideman borrows from John Mbiti’s African Religions and Philosophy (1969) to describe “Great Time” as a kind of nonlinear, “ancestral” time. Imagine it as a body of water that one paddles or swims or wades into. “There is no beginning, no end,” to ancestral time, Wideman writes. I think that Wideman offers another description of this concept in “Williamsburg Bridge,” in which the narrator recalls hearing Sonny Rollins “practicing changes” on the bridge.

Advertisement

Contemplating a suicidal leap into the East River, the narrator realizes that the bridge spans an array of possibilities, from the churning river flowing below to Rollins’s death-defying flights. The saxophonist’s improvisational play expressed “color deeper than midnight blue…Color of disappointment, of ancient injuries and bruises and staying alive and dying and being born again all at once.” One does not pass through Great Time in one direction. Instead, the artist, the listener, the reader, the imaginer, learns to float in time.

*

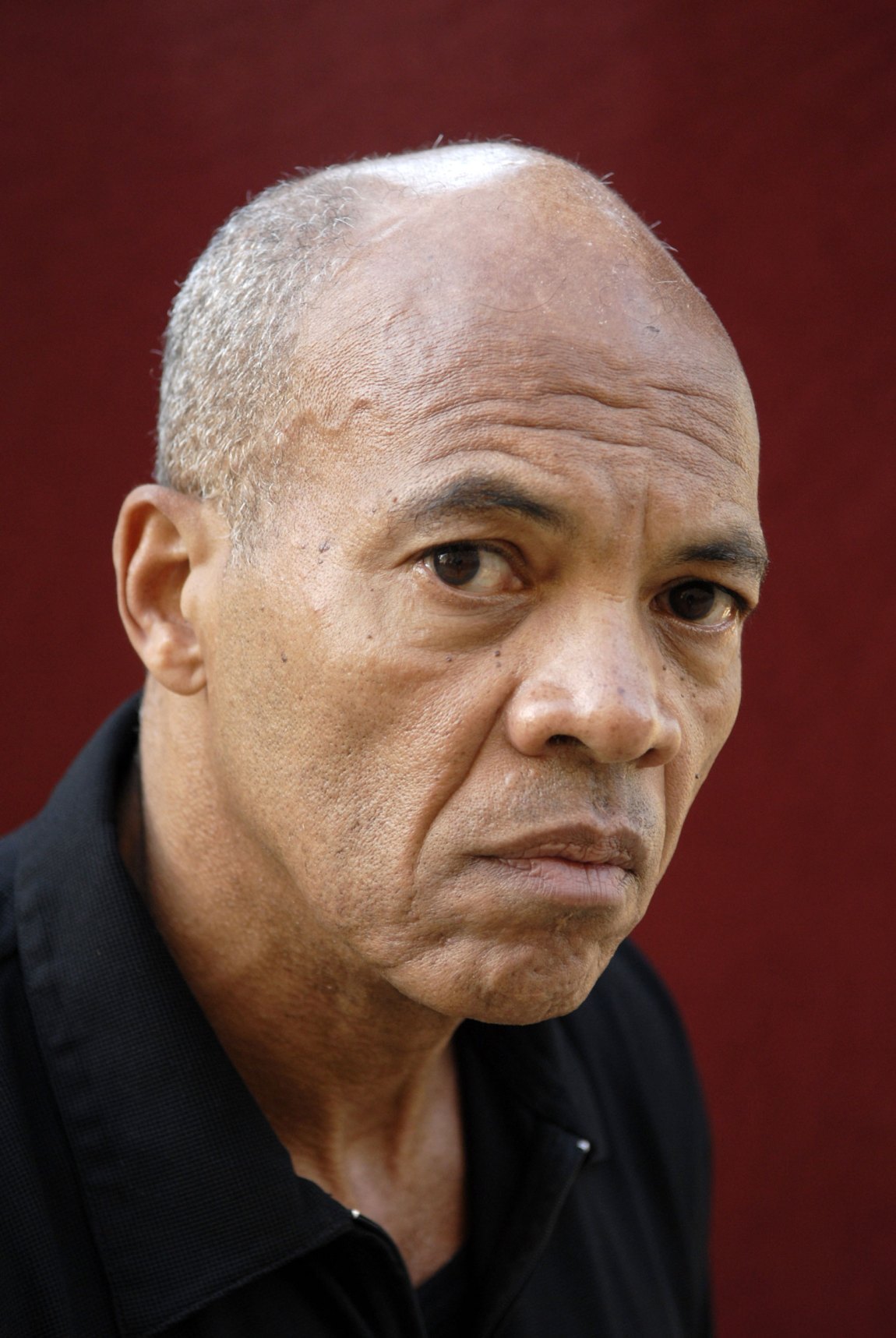

Wideman was born on June 14, 1941, in Washington, D.C., to Edgar Wideman and Bette French. Soon after John’s birth, the family moved to western Pennsylvania. Wideman excelled as both a student and an athlete, matriculating at Pittsburgh’s Peabody High School and the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia on a Benjamin Franklin Scholarship. Upon his graduation from Penn, Wideman was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship to attend New College at Oxford University. In 1966, Wideman completed a thesis in eighteenth-century British literature at Oxford and then attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He completed A Glance Away while in Iowa City and published it in 1967. Since then, Wideman has published nine other novels, five works of creative nonfiction/memoir, and six short-story collections.

Nearly thirty years have passed since the publication in 1992 of The Stories of John Edgar Wideman, a 432-page compendium of thirty-five stories from his first three collections: Damballah, Fever, and All Stories Are True. In 2021, as Wideman approaches his eightieth birthday, it’s a fitting moment for a career retrospective. You Made Me Love You, a new collection of selected stories from 1981-2018, comes at just the right time.

Though it’s actually a prefatory note of gratitude, “To Robby”—Damballah’s dedication—has the flavor and force of microfiction. With it, Wideman offers his stories to his brother, as the initiation of an epistolary exchange: “these stories are letters. Long overdue letters from me to you. I wish they could snatch you away from where you are.” In 1976, Wideman’s youngest brother, Robert Wideman was sentenced to a prison term of life without parole for his participation in a 1975 armed robbery and murder. During the late 1970s, Wideman began an effort to tailor a prose style that might capture his brother’s voice (in fiction and nonfiction). While many regard Wideman’s memoir Brothers and Keepers as a masterpiece of creative nonfiction, few have read all his stories about carceral time—“Tommy,” “Solitary,” “All Stories Are True,” “What We Cannot Speak About We Must Pass Over in Silence,” and “Maps and Ledgers”—for what they are: raw, rare gems, cut and buffed to refract a full spectrum of experience.

Also notable is the fact that Jake, Wideman’s second-born son, is serving a life sentence in an Arizona prison for killing a fellow camper during a group trip to the Southwest in 1986. Because the son did not want to collaborate with his father and has requested that Wideman not speak of him in interviews, the author has employed characters whose circumstances resemble Jake’s as catalysts for the narrators’ exploration of their own psychological states. Often, those narrators are writers.

There is a long line of death, trauma, and violence—and silence about those terrors—in Wideman’s family history. The author has acknowledged and grappled with this barbed truth in his creative nonfiction. In his stories, Wideman doesn’t have space or time to explore causes, so he drills down to the effects, elaborating the emotional consequences for characters confronting their past or repeating subtle acts of violence through silence or passing on traumas generationally as though they are genetic material or inherited debt.

*

No one in American letters sounds like Wideman. His unique, forceful musicality stems, in part, from his close study of blues idiom literature and lyricism. His career-long exploration of Black diasporic experience, his returning continually to Homewood, to visiting rooms of carceral institutions in Arizona and western Pennsylvania, his attempting repeatedly to mine his family history, to enter and understand the revolutions of his characters’ psychologies, to evoke the specific intonations of invented voices, is his fingering the jagged grain of myth, memory, and material experience. As with Ralph Ellison’s definition of the blues, Wideman’s stories arise from “an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive in [his] aching consciousness” in order to “transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy but by squeezing from it a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism.”

Advertisement

Wideman has developed a personal aesthetic influenced in part by Albert Murray’s blues theory. Murray’s Stomping the Blues (1976)—presents the blues idiom as a series of enduring, malleable forms and styles in dance, literature, and the oral, visual, and musical arts. Wideman explains that the “dues which must be paid in order to play the blues involve the same self-restraint, discipline, and grounding in idiomatic tradition to which any artist must submit.” Those practices have lasted over time because artists creating in the tradition continue improvising new ways of documenting Black life and states of human feeling. As Murray argues consistently across his works, improvisation is imperative to Black experience and to the perpetuation of the idiom. Wideman’s art is rooted in Homewood’s idiom thus, it rises from the blues aesthetic tradition and speaks universally.

It’s worth noting that Wideman has learned as much about producing blues idiom fiction from his generation of fellow writers—Toni Morrison, Toni Cade Bambara, Gayl Jones, Ishmael Reed, James Alan McPherson, Leon Forrest—as he has from Ellison or Murray. And I’ve learned as much about improvisation from reading Wideman as I have from listening to Billy Strayhorn and Mary Lou Williams, Art Blakey and Paul Chambers, Earl Hines and Ahmad Jamal, Billy Eckstine and Dakota Staton, all high-order blues idiom musicians hailing from Pittsburgh. Wideman’s experiments with form bring to mind the sensation of listening to improvisatory musical play. Take, as examples, his way of forging phrases into the run-on sentences of his characters in thought, his juxtaposing differently shaped fragments against or overlapping one another, or his taste for boxing various story swatches within the boundaries of a capacious primary story context.

Perhaps no other story captures Wideman’s improvisatory play like “The Silence of Thelonious Monk.” Reading about Arthur Rimbaud’s hellish love affair with Paul Verlaine, the narrator begins mixing the poets’ quarrelsome love story with the story of his own souring affair. Imagining the poets’ infamous standoff at Gare du Midi, the narrator constructs a motion picture of the action while recalling lines from the third section of Verlaine’s “Il pleure dans mon coeur…”: “Il pleut dans mon coeur/Comme il pleut sur la ville.” Just as Verlaine’s verse tides into narrator’s mind, it’s overtaken by the music cutting across the alleyway and into his room: “Monk’s music just below my threshold of awareness, scoring the movie I was imagining, a soundtrack inseparable from what the actors were feeling, from what I felt watching them pantomime their melodrama.”

Monk enters the narrative musically, then he quickly becomes a character in the fiction. His presence inspires the narrative’s structure, shifting as it does from the narrator’s riffing on distant lovers and potentially deadly breakups, to his direct interactions with the pianist’s silences, to his reminiscing in tempo:

Listening to Monk, I closed the book… Then you arrived. Silently at first. You playing so faintly in the background it would have taken the surprise of someone whispering your name in my ear to alert me to your presence. But your name, once heard, background and foreground switch. I’d have to confess you’d been there all along.

But Wideman’s improvisational possibilities aren’t merely musicological. They’re also physical, athletic. In “Doc’s Story,” the professor and playground legend Doc continues to hoop in spite of losing his eyesight. Doc’s prowess, his ability to feel his way through a basketball game blindly, to shoot and score guided by his other senses, suggests to the narrator that other human realities might be surmounted through faith, feeling, and inventive storytelling. Here, too, the many complex, contradictory aspects of masculinity get revised and remixed as “new rules, new priorities, that disrupt the known” forms of heterosexual Black manhood in favor of something more open, indeterminate, and emotionally available.

Drawing the body, movement, and improvisation together in language and narrative might also be called collage. Among the artists who regularly appear in Wideman’s writing, Romare Bearden, the preeminent American collagist, is especially important. The story “Collage” is Wideman’s attempt to get “Bearden to save the life of Jean-Michel Basquiat.” Set at some point in the mid-1980s, Wideman imagines the two painters in conversation while they “spray-paint graffiti in a vast graveyard of subway cars.”

The painters both produced artworks that could serve as models for the author’s approach to form in fiction. In his essay “The Architectonics of Fiction,” Wideman argues that “a story should somehow contain clues that align it with tradition and critique tradition, establish the new space it requires, demands, appropriates, hint at how it may bring forth other things like itself, where these others have, will, and are coming from.”

“Fever” is Wideman’s chief and most complex exploration of the short narrative form. The story describes Philadelphia’s devastating yellow fever plague of 1793. Wideman eschews streamlined, plotted fiction in favor of a structure that narrates the past and projects the future at once. Collaging several fragments and multiple points of view, the author follows Richard Allen, the founder of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, and his work with the prominent Philadelphia doctor, Benjamin Rush; he explores the etymological basis of “dengue” in both the Swahili and Spanish languages; he enters the consciousness of an unnamed African questioning his gods and his mortality while bound in the hold of a slave ship; he illustrates the transhistorical American fear of Black bodies as contagion carriers; and he documents how quickly those fears become feverish blisters of hatred spreading in conflagrate flares across a city (or across the centuries of the nation’s history) in the merciless stranglehold of a strange and decimating virus. In effect, Wideman has collaged an access point into Great Time.

Though this story began as his search for the source of the city’s historical, viral infection of racecraft—racism practiced systemically to produce the illusion of race—“Fever” also speaks truthfully and emphatically about contemporary America: a nation caught in the clutches of a pandemic and political malfeasance while remaining locked in civil conflict with the engineers of white supremacy. In other words, “Fever” is a daring feat of imagination. And in his design and realization of this literary collage, Wideman has produced a short fiction masterpiece.

You Made Me Love You—playful, prayerful, intricate, inviting—challenges readers to reimagine themselves radically and improvisationally. Opening yourself to Wideman’s structures, sounds, and sentences will liberate you from yourself, thus expanding and renewing your sense of self, time, and experience. This is Damballah’s instruction, this is Great Time’s bequest, and this is the meaning of the blues. Pleasure will arise from dancing with this master on his own terms and to his own tunes. Delight will come from recognizing in Wideman’s voices and silences your own intonations and noticing in his layered mélange the reflected contours of your own face.

Reading Wideman’s fiction has, for me, meant entering into creative exchange with his stories. His work has pushed me to innovate in gathering and embodying my histories and traditions—globally Black, Congolese, American—into ritual practices of cleansing, healing, reconnection, and self-invention.

Wideman is, as great fiction writers often are, a serious, intense noticer of the minuscule, intimate details of human experience. And his characters and voices reflect that careful attention: they represent humans struggling with family legacies, endemic racism and injustice, and looping cycles of community violence and economic limitation. They also laugh, sing, dance, tell stories, philosophize, mourn their dead, celebrate their living, and create beauty. Wideman doesn’t write to essentialize Blackness; his stories represent Black experience as the very seat of the practices of possibility and freedom.