Many of us who grew up in the USSR, as my husband and I did, were inevitably shaped by the worship of knowledge among the Soviet intelligentsia. It was a value that—if any could in that society—transcended politics and official ideology. But in a more practical way, education was also the only ticket to upward mobility in the USSR outside of a Communist Party career. As post-Soviet émigrés, we both carried that inheritance to America, land of freedom and opportunity, as a redoubled assumption that here, if we worked hard, our children, if they worked hard, would have a chance to study at its best universities.

And so we laid the groundwork for our children’s bright future by stretching our finances to buy a small house in a town known for its great schools, entrusting ourselves to the US public education system. Then, like many aspiring middle-class American parents, we saw to it that our children studied diligently, developed themselves through extracurricular activities, and did their share for the community, as we, too, did—all in the belief and expectation that they would be able to choose where they could study.

It was a nice story, bolstered by the “everybody’s a winner” philosophy beamed at us at parent-teacher conferences and back-to-school nights. Reality intruded, though, during our elder daughter’s junior year, when a highly recommended college counselor agreed to “calibrate” her eligibility. Inside a living room that offered stunning views of the San Francisco Bay, we learned that the colleges our daughter was dreaming about were out of reach, given her GPA, which was just under 4.0. The rest of her credentials were deemed equally ordinary. Tennis team captain? Could have helped if she were nationally ranked. Poetry writing? Sure, if she were a laureate somewhere. First generation? Yes, but it had to be first generation to college, not to America. Class president? Good, but not good enough.

“There is a college out there for you,” the counselor concluded, as the timer on the desk indicated the cost of our session, $300 and rising, “but you’d have to lower your expectations.”

The episode left us confounded and confused. Most of the colleges on our daughter’s list, which we had gamely researched together, offered no formal admission criteria. There was no published information on cutoffs for GPA, or for any other parameters. All schools touted their “holistic approach,” which considered academic achievement, leadership qualities, and personal character, singling out values such as “honesty,” “intellectual potential,” “initiative,” and “open-mindedness.” Of course. But somehow vague, generic, inscrutable. How could this be a meritocracy, when you couldn’t see how it worked?

I sought enlightenment from friends whose children have been through the process. “College admission is a black box,” said one. “A crapshoot,” said another. When we went to see a second counselor and she used the same terms to describe college admissions, we were even more rattled. We wanted to help our daughter all we could, but we held no keys to the black box.

*

Education has always been about access to opportunity. Until the end of the nineteenth century, it was limited to elites and to the reproduction of elites, to maintaining the status quo. In the West, public education only took hold as an idea as societies industrialized, creating demand for more skilled laborers and technicians, and a rising middle class. In Russia, change came later, more suddenly, and more violently, when, in 1917, the Bolsheviks overthrew the existing social order.

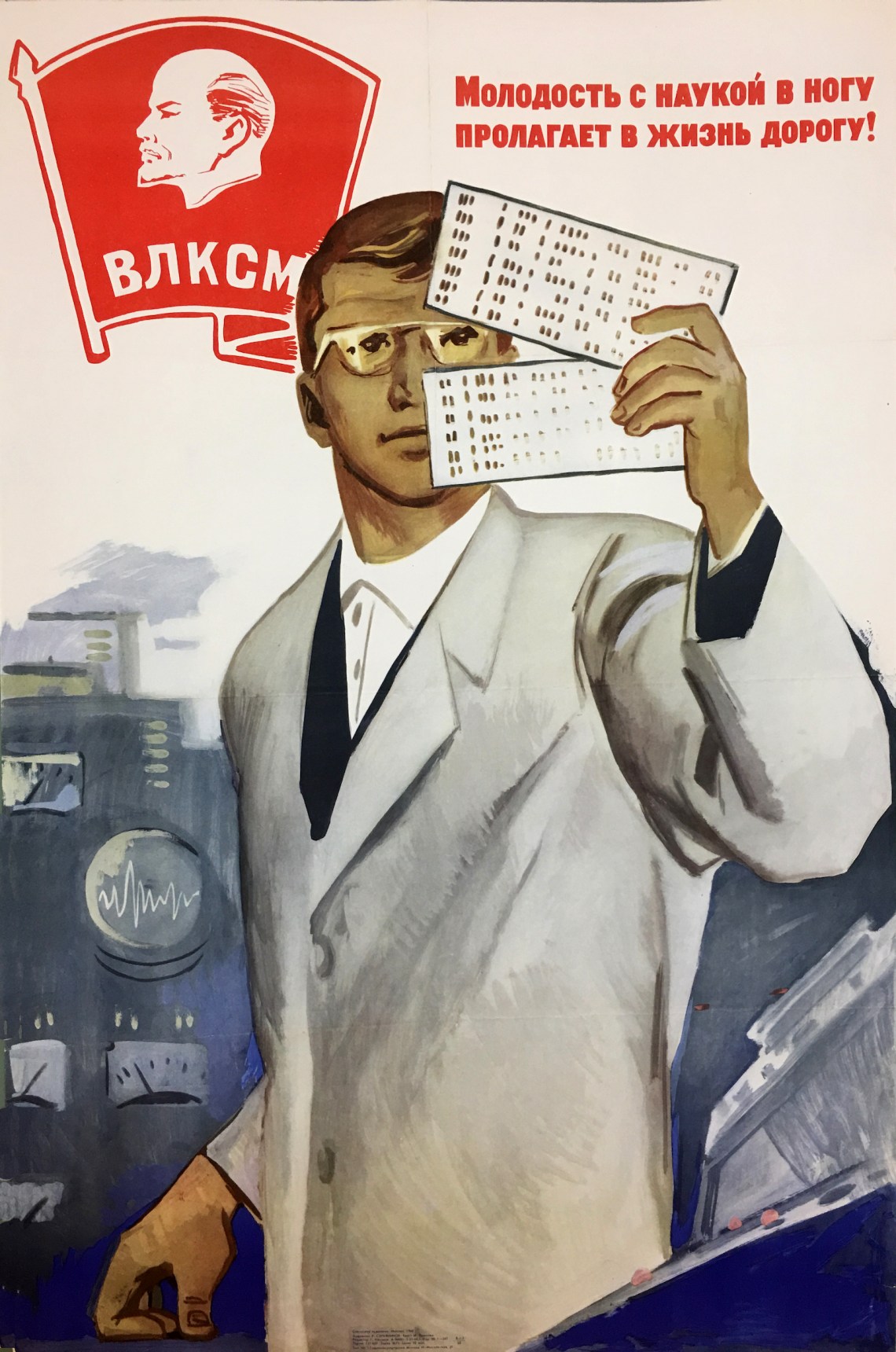

As part of its radical refashioning of society, the new Soviet state pioneered mass education by making it free and available to everyone. That state-sponsored push for knowledge came with both a political and a practical agenda. Herding the children of peasants into newly created schools and vocational programs was a way to supplant the hierarchical verities of the ancien régime with the ideology of Marxism-Leninism, and to mass produce qualified builders of socialism. “Knowledge is your compass to Communism” ran one of the popular slogans of the day.

Having demolished the old class barriers, however, the Communist Party began building its own. Heavy-handed social engineering was one of the tools. Those with “correct” class origin, like workers and peasants, were fast tracked to colleges and universities, while other entire categories of people, like former members of the aristocracy, clergy, small landowners, and other “exploiters,” were excluded altogether. As the totalitarian grinder slowly vanquished these undesirables, formal discrimination by class origin faded, but the requirement of ideological compliance remained. By my lifetime, in the 1970s, no one who was not a member of the Young Communist League (Komsomol) would be considered for admission to higher education establishments in the USSR.

Advertisement

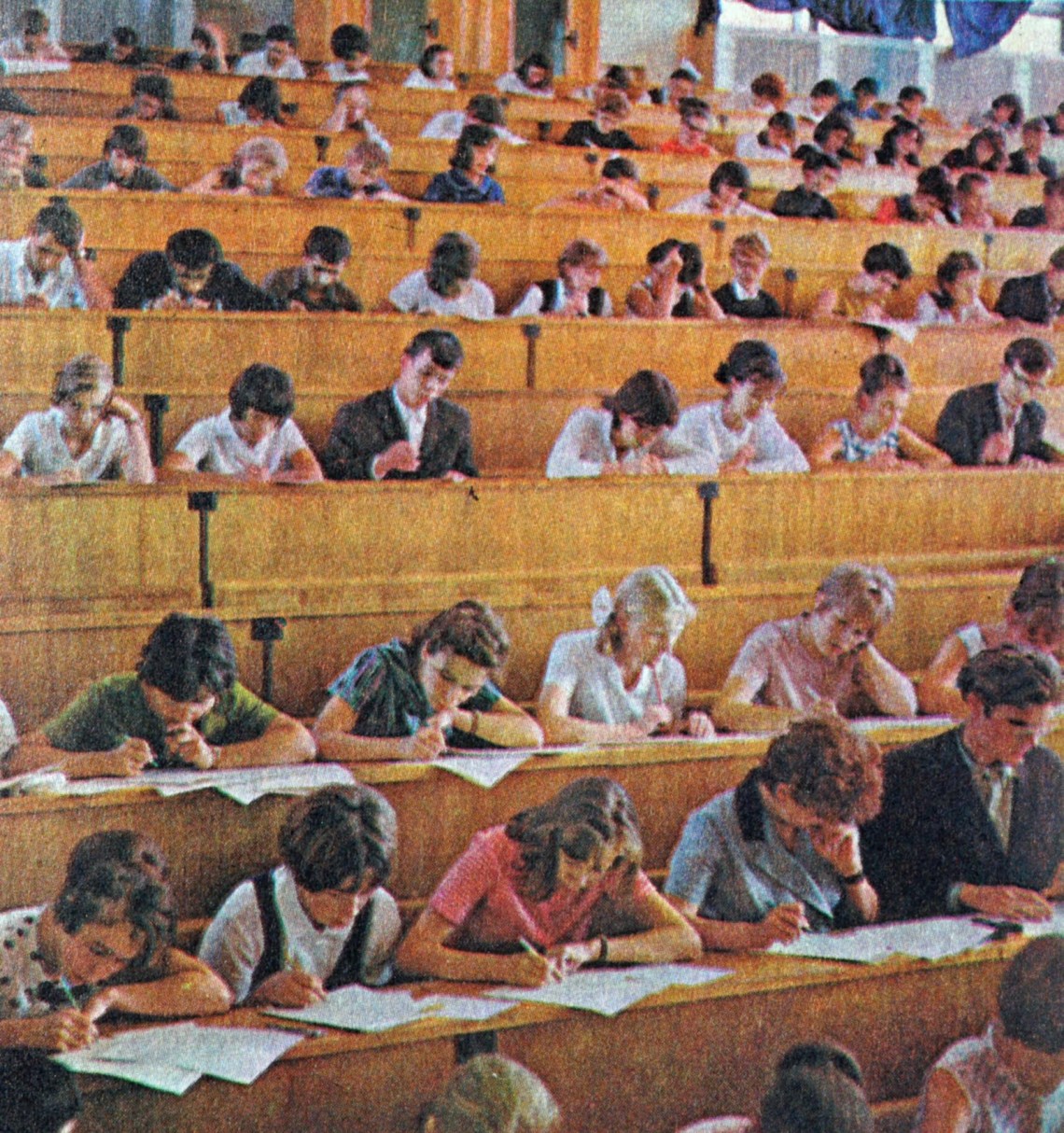

College admissions in the Soviet education system, which produced some of the world’s most qualified knowledge workforce, were a rather uniform, regimented affair. All universities and institutes followed the same admission process and timeline. After the high school state finals, graduates wishing to continue their education had to take entrance exams to the university and department of their choice (there was no such thing as undecided major in the USSR). Those with a passing score for that school (calculated as a mathematical average of your entrance exam grades) were admitted. There were no soul-searching essays explaining why you were the perfect candidate for a specific college, and your extracurriculars mattered mainly to yourself and your parents.

The Soviet system, in theory, operated on meritocratic principles that favored academic achievement, with equal opportunity for every high school graduate to succeed. Praxis differed. By the 1980s, the Soviet state had arrived at an equilibrium in which the Communist elite controlled all access to advancement and ran its own system of privileges. Top schools like the Moscow Institute of International Relations, which allowed foreign travel at a time when most of the population languished behind the Iron Curtain, were entirely off-limits for regular applicants. Access to schools a level or two below that required a serious hustle.

For many, it began with the choice of a secondary school (comprising ten years, starting at age seven, of elementary, middle, and high school rolled into one). Although all schools in the USSR were free and followed the same curriculum, some offered more in-depth instruction in subjects like math or languages. Those schools set an entrance exam and were known to have better teachers and stricter grading.

I went to one such school, which specialized in English; my cousins did the same in a nearby town. Getting in was easy enough, in fact—most of the kids in our apartment building could likely have made the entrance requirements, but not all parents bothered applying. Some preferred the convenience of a school within a walking distance; others disdained specialized schools as a preoccupation of the intelligentsia, which wasn’t at the top of the Soviet social structure.

In Soviet secondary education, student sorting happened early, by the end of elementary school (third grade). The advantage of being an A-student, recognized by a gold or silver medal at graduation, was clear-cut as far as college admissions went: you only had to take one exam in the subject you intended to study; if you aced it, you were in. The same applied to winners of regional and national so-called Knowledge Olympiads. Winners in competitive sports also received admission privileges.

But there were no guarantees, and the most desirable institutes of higher education graded entrance examinees ruthlessly in order to regulate their intake. My award-winning straight-A classmate, for instance, received four straights Fs in her entrance exams to the town’s Medical Institute. The problem was not any deficiency in her knowledge, but the fact that her parents lived in Moscow and had mistakenly assumed a provincial medical institute would mean an easy pass for a gold medalist.

My mother, accordingly, left nothing to chance. At the beginning of my high school senior year, she hired an English tutor. By then, I already knew more than enough to pass the English entrance exam built on the non-specialized academic curriculum, but the tutor taught at the department of foreign languages at our local university, where I wanted to attend, and the expectation was that the entrance committee typically didn’t discriminate against their own. I saw this tutor every week for a year, studying over the same textbook we had in school, as an insurance policy. It paid off one August evening, when, amid an anxious crowd besieging the doors of the university, I traced my name in a posted list of those admitted.

Having the “right” nationality could also be a path to admission. This didn’t apply to me, an ethnic Russian, but high-profile universities in Moscow and other cities reserved a number of spots for non-Russian ethnicities from the Soviet republics. Upon graduation, such students were required to return home and put their education to use in their native republics. If your ethnicity happened to be Jewish, however, it worked against you: the late Soviet state was anti-Semitic, and Jews were routinely excluded from the top colleges.

Work and service offered two other known routes. Some factories reserved spots for specialists in so-called target areas, but you’d have to return to the factory that sent you. Or you could get a job anywhere, with no obligations, and enroll in a one-year preparatory course at the university of your choice; completing it with good grades pretty much guaranteed admission the following year. Young men who’d already served their mandatory military service also had admission privileges.

Advertisement

Failing any of these methods, there were still two possible pathways: bribes and Blat, or connections. Every summer, before college enrollment, gifts for our first-floor neighbor, who sat on the admission committee for the local Institute of Commerce, arrived by the truckload. As for connections, Nikita Khrushchev had once complained that Soviet higher education was polluted by the progeny of parents with privileges; by the Brezhnev era, Blat was simply a fact of life—a way to survive in the stagnating late Soviet economy was though the exchange of favors. Those networks were mostly local and so a leading reason for why I didn’t try for a Moscow college; we had no connections there.

Then, while I was still an undergraduate, everything changed. The USSR ceased to exist, and the world opened up. In 1995, I was awarded a British Council scholarship to study for an MBA in England. I was accepted by three universities and, knowing nothing about any of them, chose the one closest to London. And that year changed my life: I got a graduate degree, a new career, and an opportunity to live in the country whose language I’d been learning since third grade. I chose to move to the West permanently, and ultimately the United States, because life here seemed fairer than in my native country: if you studied and worked hard, you had opportunities. By and large, the expectation held up. Then came my daughter’s college applications in 2020.

*

Undeniably, some of this year’s college admission chaos was caused by the pandemic. In California, where I live, schools were shuttered in early March. Spring semester grades, a critical component of a high school GPA, were reduced to a simple pass/fail for many. The SAT test was cancelled for seven straight months, with the College Board, one of the organizations responsible for test administration, unable to offer any alternative arrangements. ACT, the other test company, was more flexible, allowing kids still to take the test, though in unconventional venues and often at very short notice. Campus tours were cancelled, leaving seniors studying websites, as were all in-person extracurricular activities and community service. What should have been the culmination of the high-school experience turned into an indefinite chain of Zoom calls.

Colleges across the country responded to the turmoil by going test-optional and by emphasizing their “holistic review” of candidates’ applications. The decision to go test-optional proved a mixed blessing: while enabling kids who couldn’t take the SAT to apply, it also removed one of the few hard criteria, creating a glut of applications. UCLA, California’s most popular public university, saw an all-time high of more than 200,000 applications, with similar increases registered at Berkeley, Santa Barbara, San Diego, and Davis. Applications to competitive private colleges also went up. At the same time, the number of available spots dropped because previously accepted students who’d taken a gap year at the beginning of the pandemic, at higher rates than normal, had to be accommodated in 2021.

As in other areas of our lives, the pandemic only exacerbated existing trends. It is no secret that the number of places at most top schools has not kept pace with population growth, remaining nearly the same in 2021 as it was in the 1990s. This works for the schools—increased demand and limited supply means they’re assured of plenty of applicants—but for students, not so much. Every year brings fiercer competition. And as we discovered, a whole cottage industry exists around undergraduate admissions, with an army of educational consultants offering to “calibrate” and “package” your child for specific colleges.

Those retainer-based relationships start as early as freshman year of high school and guide students in everything from course curriculum to community service choices. Add to that extras like test tutors, essay-writing coaches, and financial application consultants, and you can be in debt before even seeing a tuition bill. Parents are forced into the race because they’re afraid they’ll put their child at a disadvantage if they don’t.

It doesn’t help that there are no unified admission criteria and colleges’ needs alter from year to year without being advertised. Take a simple parameter like GPA. Each college uses its own way to calculate it, assigning different weight to regular and advanced courses; some include freshman year’s grades in their calculation, others don’t; some rank students, others make a point of not doing so. High schools themselves are being rated by admissions officers, who weigh an applicant’s GPAs against grading policies or against socioeconomic backgrounds. One thing you quickly learn after going through American undergraduate admissions is that there is no such thing as “average GPA.”

Then there’s the holistic review, or an undertaking by colleges to take into consideration candidates’ qualities beyond those shown by grades and test scores. The idea that it is possible to make accurate character appraisal in the five minutes that large schools like UC Berkeley spend, on average, per application review is obviously questionable. Holistic review rejections can be particularly demoralizing for the student since they carry an implicit personal judgment. Even admission by lottery would feel more humane.

A process so lacking in transparency lends itself to abuses that make Soviet-era Blat seem almost innocent. The 2019 college admission scandal, uncovered by Operation Varsity Blues, revealed the extent to which some parents, with the connivance of corrupt officials, are willing to go to get their kids in: a special test-taking center, where a bribed proctor ensured a perfect score; doctored athletic achievements followed by a large donation to the sports team in question. Others try to game the system, be it through obtaining special dispensation for “text anxiety,” or by tailoring personal essays to key off the zeitgeist. All of this opacity, inequity, and elite machination plays into the cynicism and resentments already ripping our society’s fabric.

As is often said, a crisis can create an opportunity—and the disruptions of the coronavirus pandemic may be a chance to rethink our approach to higher education. The transition of many colleges to virtual and hybrid modes of instruction has shown that limitations of physical space, often cited as a reason for keeping the number of spots low despite the demand, are not an insurmountable obstacle. If you’re teaching online, you can admit millions, if you want to.

Add to that an in-person component—perhaps by renting space across the country, to mitigate the downsides of online-only learning—and you will have a viable new way to extend competitive education to all those qualifying and willing. It would be better than putting thousands of qualified applicants on waitlists, leaving them for weeks, sometimes months, in a state of suspense, and with no guarantee of a positive outcome.

A century ago, the Soviet experiment—for all its manifest and tragic failings—demonstrated how broadening the path to education could help propel a backward, agrarian country into an industrialized superpower in less than two decades. Today, in the face of technological change that is replacing many jobs with automation, aggravating socioeconomic dislocation, America’s top colleges cannot stand back and watch access to good education slipping out of the reach of the country’s middle class. They should pitch in to the efforts of the federal government that has been backing broader access to higher education for decades, from the GI Bill to Pell Grants, by making their coveted degrees available to everyone with the aptitude and the qualifications. To do so, they could either offer hybrid degrees, or increase admission numbers, or both. And these centers of learning could surely devise other solutions besides.

Standardizing college admission criteria and making them more transparent would be another crucial step toward making the admission process less of a black box. The year of college admissions shouldn’t be a year of anxiety and stress for students, nor should one’s parents have to spend inordinate sums on “packaging” their children. The focus ought to be on helping them understand who they want to be and on equipping them for the challenges of tomorrow’s world. Our children should have knowledge as their compass—to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.