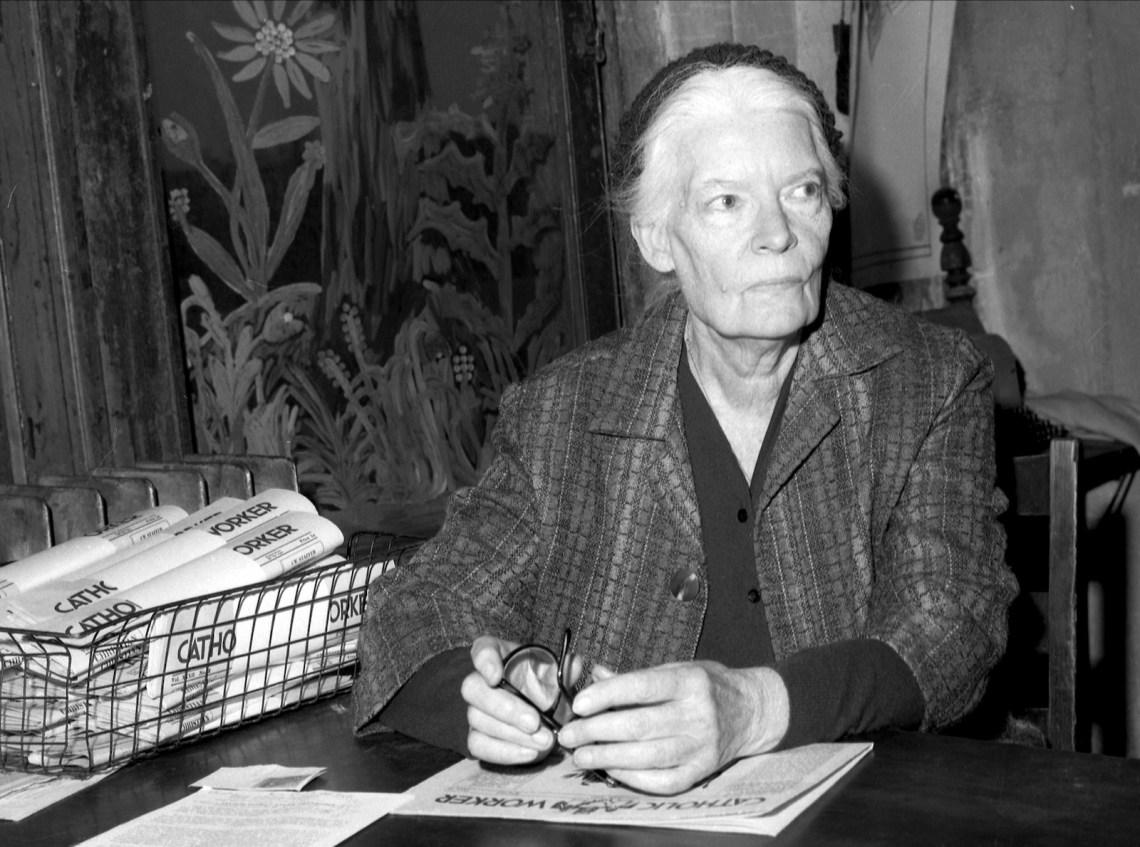

Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan, archbishop of New York, has just sent documents to the Vatican requesting that the left-wing writer and activist Dorothy Day be declared a saint. I hope that does not happen. The late Jesuit priest Daniel Berrigan said that canonizing Dorothy Day would be a demotion. She herself said simply it would trivialize her. She is larger than the figures who wind their way through the miniaturizing process of canonization.

She has already passed the first test: a million dollars has been spent turning up all the documents to prove she did not bulk out awkwardly beyond the coloring lines of theological orthodoxy. There used to be an office called the Devil’s Advocate for challenging any assertion of perfect rectitude. Now the same test has been internalized by the promoters of her cause. Oh yes, Cardinal Dolan admits, she kept bad company—Communists, for instance—before her conversion to the Church, but not after. This is a necessary pruning of her life, because the ruling premise is that there cannot be a Communist saint. In fact, I have known many communist (with a small c) saints, who kept the essentials of Marx on the nature of capitalism without the (large C) Communist excesses of Stalin on state power. G. K. Chesterton was one, and so was Studs Terkel, and so was she. But that will never do if she is to pass the doctrinally prettying process of canonization.

Another example of this miniaturizing was the promotion of the nineteenth-century English theologian John Henry Newman toward sainthood, which Pope Francis passed in 2019. Those who advanced Cardinal Newman’s cause thought they could “saint him up” by separating his body from the scandalous grave he shared, by his own firm order, with his beloved Ambrose St. John, and moving him to a future shrine at his Birmingham Oratory, moving him back to his own side of the bed, as it were. Exhuming him would have the extra advantage of supplying first-class relics from his body or clothes. But the grave raiders were thwarted when they found that their bodies had totally rotted away through their wooden caskets in damp ground.

That canonization effort was motivated by a premise similar to the one on Dorothy Day’s part. The major impediment to her canonization is that there cannot be a Communist saint, according to a decree issued in 1949 and approved by Pope Pius XII. For Newman, the premise was that there cannot be a gay saint—though, once again, I have known and admired many gay Catholic saints, both inside and outside seminaries and convents.

Even after one gets past the recorded or invented doctrinal soundness of a candidate, there is still the matter of collecting three miracles purportedly worked by her mediation. For this step, one must not only believe in miracles, but also in the possibility of tracing any miracles to the saint-to-be’s intercession. The right combination of a self-identified prayerful person, a recordable miracle, and an identifiable enactor must be secured.

This is not an easy job. For starters, why would a person pray to someone who has not yet been sainted, rather than to any of the whole range of those already lodged in heaven by decree of church authority? One would expect a rational person to hedge his or her bet by at least giving the senior partners a chance at bringing off the miracle. But no, we have to take the word of the person praying that he or she was addressing mainly (preferably solely) the candidate.

That is why most canonizations begin with the new saint’s promoters saying, Find me miracles—much as former President Trump told a Georgia official, Find me votes. This part of the process is just as time-consuming and expensive as the documentation of the candidate’s life. Luckily for them, most religious orders can devote their entire personnel and their fundraising prospects to getting their founder canonized. The effort returns them a high profit, on success, in shrines and relics and festivals for the founder. Similar advantages are offered to nations or causes or locales that want a saint to their name.

Nor should we forget that popes tend to canonize popes, or other persons they favor, as when John Paul II sainted Josemaría Escrivá, the founder of Opus Dei, in 2002. He also highly favored the creepy predator Marcial Maciel, the founder of the Legion of Christ, but could not canonize him because, inconveniently, he was not then dead.

The entire canonizing matter is highly political, as when Pope Francis tried to unite the church by simultaneously making saints of John XXIII and John Paul II. Some Catholic leftists like me thought John Paul II a disgrace not so much to his office (which did not matter), but to the cause of mankind (as evidenced by his constant commitment to condemning condoms when that meant a death sentence to gay people during the AIDS plague). The balancing act comes from the fact that right-wing Catholics hold John XXIII in a symmetrical contempt.

Advertisement

The ecclesiastical bureaucracy that oversees the certification of miracles cannot reach its goal, of course, until the pope legislates. This is a backdoor way of affirming papal infallibility: Who but an infallible person knows who is in heaven and can reward prayer to him or her, establishing an official feast day in the liturgy of the Mass, sanctifying related relics and shrines? This is as gratifying an exercise of power, for some popes, as proclaiming the size of his crowds was for President Trump. I see that impulse at work in John Paul II’s happy record of racking up 482 saints, compared with the three hundred canonized in the preceding six hundred years.

Taken all in all—the doctrinal trimming, the hunt for miracles and their supposed verification, the trade in relics, the commercialization of shrines, the papal politicking—how can the greatness of Dorothy Day not be shrunk, rather than enhanced, by the whole silly affair?