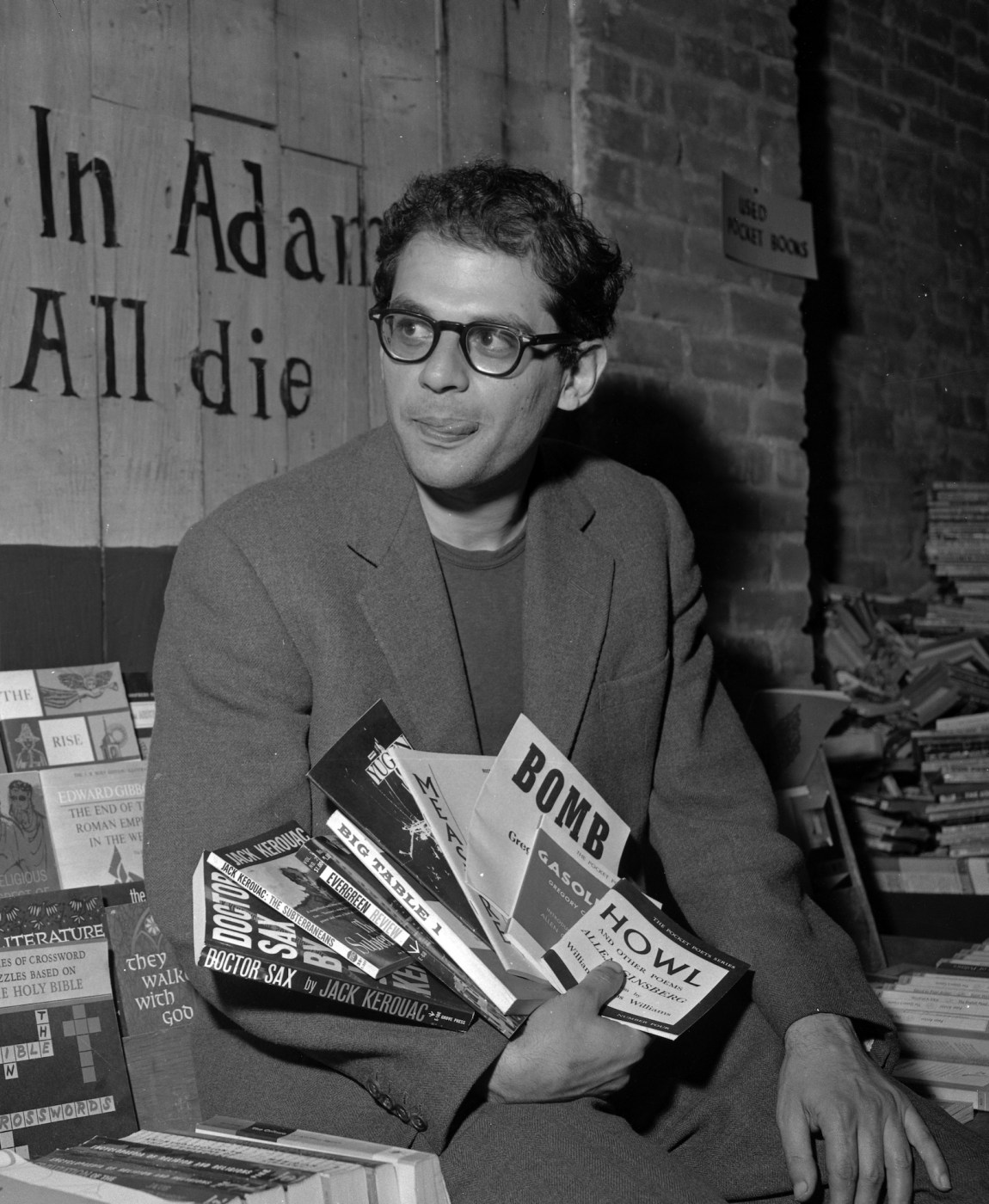

Most books come out and vanish pretty quickly, leaving a trail of silence behind them. In 1950, that had been the fate of Jack Kerouac’s first novel, The Town and the City, when, despite a promising initial flurry of attention, the twenty-eight-year-old writer soon realized he need not have worried that losing his obscurity might be bad for him. Now it was halfway through 1957, and none of his other work had been published, although he’d kept stubbornly writing his unacceptable novels. There were five of them by now—all “published in Heaven,” as Allen Ginsberg had put it in his introduction to the pocket-size paperback of Howl, which had just been seized by the San Francisco police.

Howl had been impounded on the grounds that its title poem was obscene, though perhaps that had only been an excuse to suppress it. While “Howl” was just a poem by a relatively unknown poet published by the small, brave City Lights press, it was dangerous with its fierce indictment of America as a Moloch that devoured its young and those who did not live according to its norms. It had come out at a time when there was little open dissent in America; memories of the lives that were ruined earlier in the decade during the hearings of the House Un-American Activities Committee had not lost their potency.

“Imagine,” Jack wrote me from Berkeley, in June, soon after the raid on City Lights, “one woman writing in the paper if Jesus Christ was alive he would have led the police to the bookstore to impound HOWL! and all that kind of negative old woman attitude all over the place with all those new dreary neat cottages and clean streets with white lines and signs that say WALK, STOP, DON’T WALK…I can’t stand it….” He said he was sorry he’d ever suggested my coming to California, since he could “foresee being driven out of America altogether.”

If Howl had been impounded, what would happen to On the Road? Jack’s greatest fear was that, given the heightened appetite for book-banning, Viking Press would decide against publishing his second novel, which it was supposed to bring out that September.

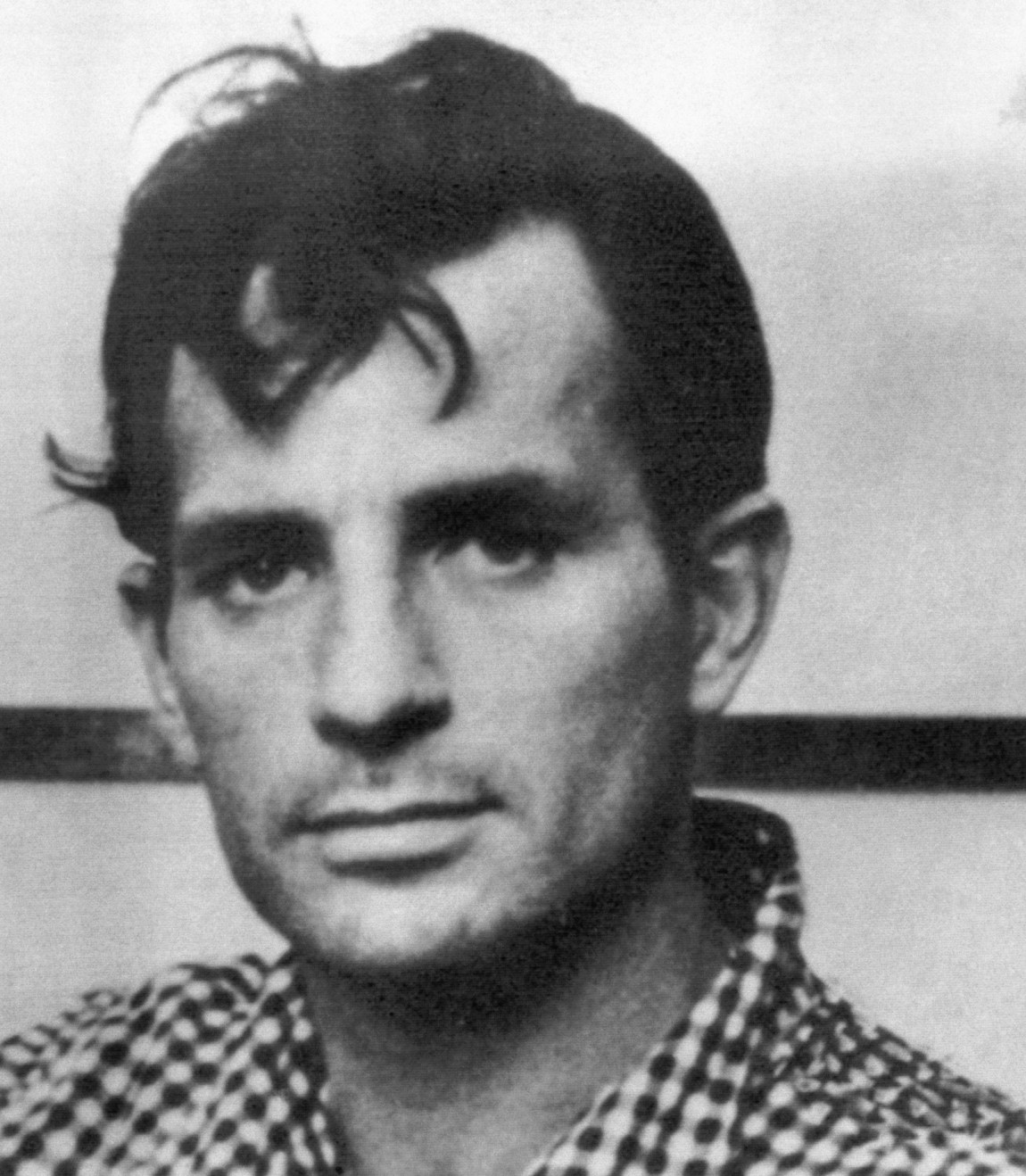

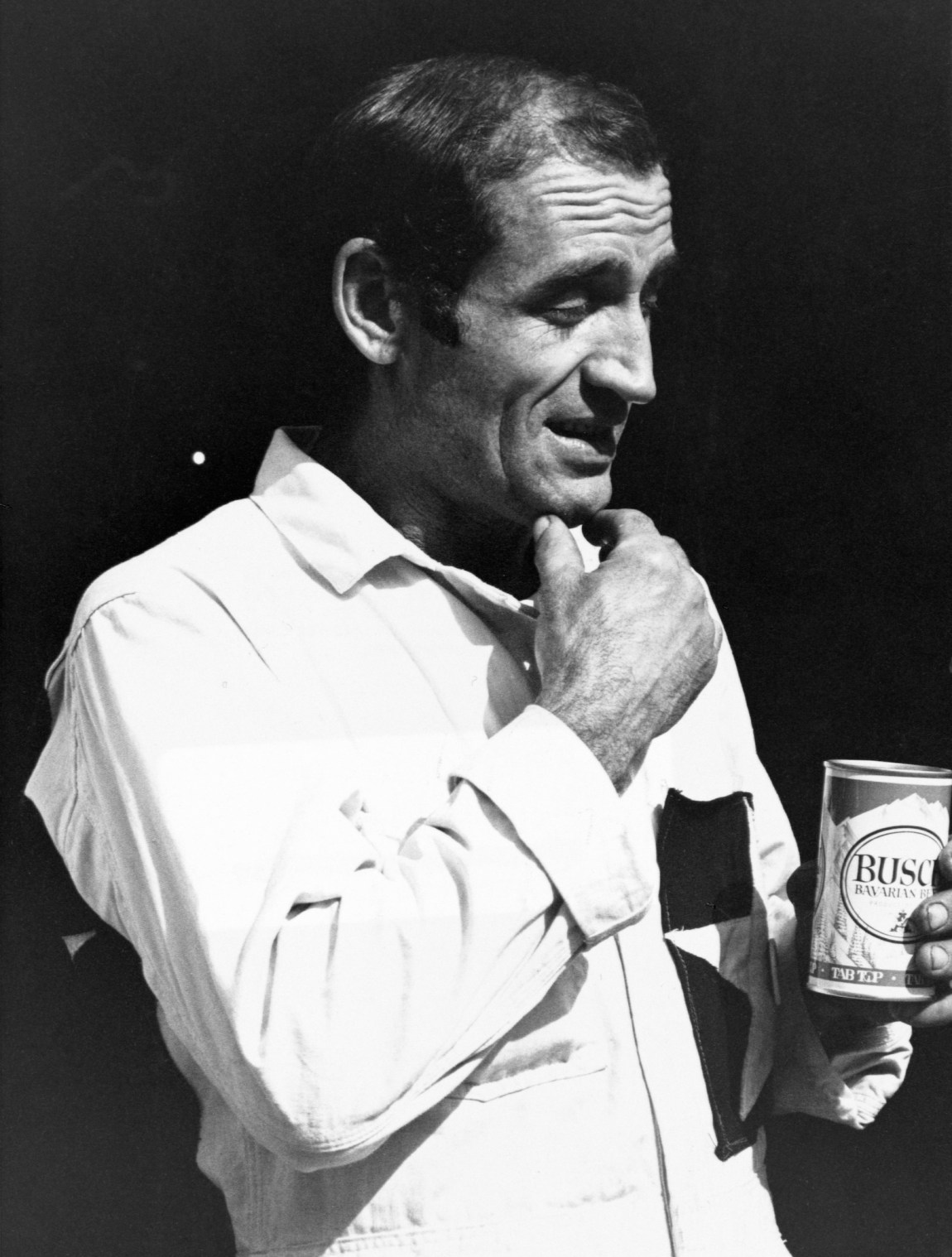

Of all his books, On the Road had been the most difficult one to write, although the original idea had come to him twelve years earlier, not long after the war: a young man trying to lift himself out of a pessimistic mood after a debilitating illness takes a road trip across America that he hopes will reinvigorate him, encountering a series of symbolic characters. Jack had jotted those first thoughts down in a notebook even before he met Neal Cassady, a rootless Western youth who had been raised in a Denver flop house, taken joyrides in one stolen car after another during his teens, and had more restless, dynamic energy than anyone Jack had ever met, as well as a riveting, digressive way of speaking and writing letters. In the summer of 1946, after Neal, then twenty, had streaked through New York with his sixteen-year-old bride and returned to Denver, Jack took the first of his hitchhiking trips westward to reconnect with him.

In his first attempt to write On the Road, two years later, Jack merged himself with Neal in a character called Ray Smith. After that fictional protagonist had been scrapped, there would be a succession of others, each with a Neal-like alter ego. Meanwhile, Jack remained determined not to write a second autobiographical novel (there was a prejudice in those days against fiction writers who worked too closely from their lives), but the story he wanted to tell refused to be fictionalized in any version he came up with. In the summer of 1949, the two main characters were half-brothers whose father was a Colorado rancher; by the fall of 1950, they’d become a twelve-year-old Franco-American boy and his uncle; abandoning that idea, Jack then tried to write the whole thing in French. But none of those efforts, some of them lengthy, were good enough to hold his interest. They each lacked a voice that met some indefinable standard of perfection in his mind.

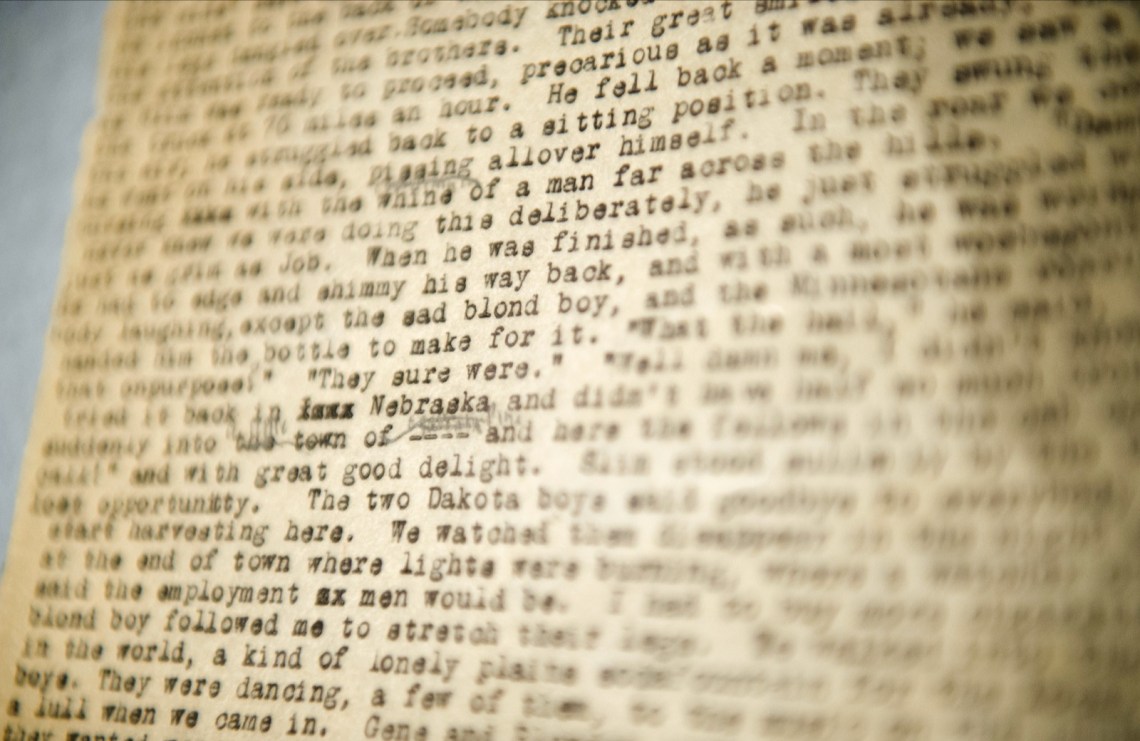

Then, in the spring of 1951, following an outpouring of letters to Neal filled with Jack’s childhood memories, and the composition of a memoir-like novella La nuit est ma femme, On the Road came to him whole, like a poem, carrying with it the first-person, subtly French-inflected voice in English in which he should have been writing it all along, filling him with such certainty about how to get it down on paper that he wrote the book straight through in three days. Eliminating opportunities to interrupt the high of his initial rush of imagination—the second thoughts that might come as he put a new page in his Remington—he’d typed it as one continuous paragraph on a scroll he’d made by glueing together sheets of Japanese drawing paper.

Advertisement

He had loved On the Road in its raw original form, before he’d changed the names of any of the friends he wrote about or his own, French one. But right away, in order to get editors to consider it, he’d had to make it less great, breaking up his river of words as he chopped it into paragraphs and chapters, sitting so long at the typewriter as he retyped the whole thing that he nearly died of thrombosis and ended up in the hospital. And after all that, no one had wanted it anyway—until Viking bought it in 1954, and then shelved it for the next three years, unwilling to let it go but reluctant to put it into print.

It was probably the rising interest in the Beat Generation that made Viking finally decide to publish that fall of 1957. And now, Jack felt, even that was in doubt, despite all the editing he’d reluctantly agreed to. He had done something himself to On the Road that he was secretly ashamed of: he had made his protagonist, now called Sal Paradise, into an Italian American, fearing that people wouldn’t want to read about a Canuck.

By July, Jack was in Mexico, where whatever happened to On the Road in the States would be a very distant rumble. Writing to me hours after a huge earthquake had rocked his hotel and leveled portions of Mexico City, he urged me to join him there as soon as possible. “We’ll do our writing and cash our checks at big American banks,” he wrote, “and eat hot soup at market stalls and float on rafts of flowers and do the rhumba in mad joints with ten cent beers.” When we got tired of all that, Jack said, we’d move to a cottage “with flower pots in the window” in some very quiet village—though he didn’t specify how long we’d be there.

I had to go. “Do what you want. Always do what you want,” he’d always told me in the six months that I’d known him—but now he was saying he needed me. I was twenty-one, and I was about to get a check for five hundred dollars—which Jack said would last me for a year—because I’d just sold the novel I was writing to a publisher. And as Jack had quickly understood when he met me, I was looking for something, some big romantic adventure that would sweep me away from anything resembling one of those constricted little lives ordinarily assigned to young women. Evidently, I’d been turning Beat for a few years without knowing it. So, as soon as I could, I gave up my job as a publishing secretary in New York City and my gloomy furnished apartment near Columbia, and bought a plane ticket for August 21.

But a week before I got to use it, Jack left his hotel room on Orizaba Street, with its cracked ceiling, and went to his mother’s house in Orlando, Florida. He needed to recover there from a bout of flu; he’d been too sick and too broke to wait for me in Mexico. “I don’t want you to be confused,” he wrote, promising to see me in New York very soon. Despite Jack’s fears, On the Road was coming out on schedule.

On September 4, looking weary from his long journey, he walked into the brownstone apartment I had just moved into on West Sixty-Eighth Street. I had wired him the thirty dollars that enabled him to travel by bus; otherwise, he would have had to hitchhike. Jack had no idea that his hitchhiking days were about to end permanently, or that, in a little while, thousands of Americans would know his name, making “Kerouac” almost a household word.

I remember he was wearing a bright-blue Hawaiian shirt that I thought was going to look weird in the gray-flannel capital of the world. How unprotected it somehow made him seem. He was still wearing it as we stood at midnight by a newsstand on Sixty-Sixth and Broadway, reading the review that had just come out in the morning edition of The New York Times. Jack seemed more stunned than excited when he handed it to me and asked if it was good. Just the words “historic occasion” in its opening sentence told me it was spectacular. By pure chance, On the Road had found its ideal reader in Gilbert Millstein, the Sunday Times staffer who was subbing for the daily reviewer, Orville Prescott. When Prescott got back from his vacation, he would tell Millstein that he would have written how much he loathed On the Road. He would never ask Millstein to review another book.

Advertisement

Comparing Jack to Ernest Hemingway, Millstein pronounced him the “avatar of the Beat Generation,” praised the “almost breath-taking beauty” of his writing, and wrote in such a passionate way about the “search for affirmation” undertaken by Jack’s characters that it sounded as though he’d recognized it as his own search as well. Although Millstein, who was in his early forties, had tried to maintain an objective tone, it was clear that he identified strongly with the Beat Generation, who, as he put it, had been “born disillusioned,” and grown up feeling the weight of “the immanence of war, the barrenness of politics and the hostility of society.” The Beat Generation was “not even impressed,” he wrote, “by material well-being…. It does not know what refuge it is seeking, but it is seeking.”

Millstein suggested that On the Road might be “condescended to” by “the neo-academians and the ‘official’ avant-garde critics,” whom it might “make uneasy.” There was also the possibility that it would be dealt with superficially by those who did not understand its importance. But the uproar that would begin the following day would go far beyond anything Millstein anticipated.

Although On the Road was in no sense a protest novel, Jack had written something with tremendous subversive power. At a time when the United States was becoming blinded by its postwar success, he had looked past the American dream and projected a very different way of being in a voice that was extraordinarily compelling to those whose accumulated angst was at the point of boiling over. After the long wait that had been so costly for him, On the Road had come out at exactly the right moment.

“I need a drink,” Jack said, as we walked away from the newsstand. I couldn’t figure out why he still didn’t seem to share my excitement. He read the review a few times more as we sat in a bar on Columbus Avenue, but did not say what he was thinking. Not until sixty years later did I find a clue to what may have been on his mind as I read a page in one of his 1957 notebooks in the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library. The Jack Kerouac Archive had only recently become available for research there, after being withheld from scholars and a succession of frustrated biographers for four decades.

While he was alone in Mexico City, Jack had realized that he no longer believed in the Beat Generation. It was nine years since he’d first named it, in the midst of a conversation with his friend the young novelist John Clellon Holmes that had thrilled both of them. But now, he felt it no longer existed—not in the way he’d first thought of it, or with the people he used to call “furtives,” whose lives as “illegals” had inspired him in 1948. Most of them had soon “disappeared into jails or houses” rather than forming a subterranean spiritual movement that might spontaneously rise to the surface. Meanwhile, Holmes had run with his idea, and changed it —while giving Jack due credit—in an article titled “This Is the Beat Generation” that appeared in the Sunday Times Magazine in 1952.

Jack’s Beat Generation lived out on the margins of American society, where they had learned to “exist from the bottom of their minds outward.” They included drug addicts like the ones whom Jack had encountered on Forty-Second Street, outlaws like Neal Cassady, and Black people. He, too, felt like one of these furtives, with his unacceptable identity as a Franco-American, his poverty, and his low expectations for success. (In On the Road, Sal Paradise would chide himself for having “white ambitions.”)

Yet Jack’s original vision was wildly hopeful. With a “vanguard of fed-up Black beboppers,” he could imagine the Beat Generation’s forming a great procession that would lead the world “out from under the shadow of the atomic bomb” into a future of joy and “apocalyptic love,” as he explained in a letter to his skeptical acquaintance Alan Harrington in December 1948. (In the Berg Collection, I found the copy Jack had made for himself.)

The Beat sensibility, as Holmes saw it four years later, was already unconsciously shared by many younger Americans. It needed only to be recognized to be widely embraced. The Beat Generation he described in his article was, implicitly, middle-class and white, even privileged. Disaffected young businessmen replaced Jack’s “furtives.” A fresh-faced suburban teenager, rather than a habitué of an all-night cafeteria on Forty-Second Street, spoke of how she found community when she smoked marijuana with her friends. Jack’s vanguard of Black beboppers was nowhere to be found. I was a sophomore at Barnard College when the article came out, and I can remember the students I knew talking about it, wondering if that word Beat applied to them. It had, in fact, been Gilbert Millstein who had commissioned Holmes’s piece for the Times, and it was their shared conception of the Beat Generation that caused a furor in 1957, although much of the rage and disapproval provoked by the label would be directed at Jack.

Incensed columnists warned their readers that if America went Beat, there’d be a wave of juvenile delinquency. Academicians at Columbia, Jack’s alma mater, shuddered in their ivory tower and prepared to defend the Literary Tradition. The Henry Luce publishing empire immediately went to war, perceiving the Beat Generation to be so threatening to the status quo that it had to be quickly neutralized and made trivial. Life magazine hired models and did a photo shoot of a typical slovenly Beat household, complete with bongo drums, beer bottles, low-cut blouses, suspicious-looking cigarettes, and a neglected baby in diapers crawling across the floor. (A lot of young people thought that relaxed way of living looked like fun.)

By October, Herb Caen, a West Coast newspaper columnist, coined the patronizing word Beatnik. The Beat Generation—as it was co-opted into a lifestyle that anyone could try on and take off, like a black beret—became trendy. A novelty company brought out a Do-It-Yourself Beatnik Kit that later turned up in flea markets as a vintage collectible. The co-optation process has continued into this century, sometimes under the guise of homage. In London, last fall, models in Beat menswear designed by Dior paraded down a runway, treading upon a facsimile of Jack’s On the Road scroll.

“I don’t want imitators,” Jack would say, sternly. One night, he had a disturbing dream about being followed by a mob of avid kids shrilly chanting, “Kerouac! Kerouac!” “Fuffniks’ fan mail,” I remember him saying wearily when I brought him the latest pile of it that had been stuffed into my mailbox. Because he had a deep vein of shyness, he’d fortify himself before his interviews on TV by getting drunk, which would only make him feel more defenseless when he was grilled about what he was looking for. “I’m waiting for God to show me his face,” Jack said on Night Beat, sweating in the hot, white glare of the NBC studio.

Critics associated with the influential Partisan Review, which was being secretly funded by the CIA during the late Fifties, seized opportunities to refuse to take the Beat Generation seriously, while according to the Saturday Review, a “chimpanzee running a temperature” had written On the Road.

Hoping to open the closed mind of Norman Podhoretz, who had been writing some of the most vehement attacks, Allen Ginsberg invited his former Columbia classmate over to my apartment to meet Jack and have a serious talk about the Beat Generation. I made coffee and left them to it. Just by the rising volume of their voices, as I sat in the next room, I could tell it wasn’t going well. As Podhoretz went angrily down the stairs, Allen shouted after him, “We’ll get your children!”

Jack was always willing to tell a reporter the story of his breakthrough—how he’d written On the Road in only three days. Everyone was fascinated by the scroll, which over the years became an icon to his fans. His account of nonstop writing had the elements Americans most liked to hear about—speed, physical endurance, ingenuity. But in the interest of telling a good story, he had left out too much—those years of fruitless work preceding his breakthrough. This gave some critics the ammunition they needed to dismiss his writing completely. The most devastating put-down came from Truman Capote: “That’s not writing, that’s typing.” As Gertrude Stein reflected, in 1938, years after seeing Parisians try to scratch the paint off a Matisse, “Everything new is ugly.”

In the summer of 1958, after being attacked and beaten outside a MacDougal Street bar, Jack decided he needed to rest his mind in the brown-shingled house he’d just bought for his mother in Northport, Long Island. There, switching from cheap wine to scotch, he stayed drunk and got nowhere with his next novel, Memory Babe, as he sat in his new writer’s study at the oak roll-top desk he’d always wanted. He sent me a line—Pay Me the Penny After—from the novel he wasn’t writing in case I wanted to use it as a title for mine. Was it a gift or a message, I wondered.

In Northport, he had not found solitude. Carloads of teenagers would arrive to bear him off to their beach parties, like a captured trophy. “How do you get an apartment in Greenwich Village?” a girl of seventeen with a perfect tan asked me, on my one trip out there, making me feel very old. In the fall, Jack visited me in New York, but I saw him only a few more times after that. I was married and the mother of a three-year-old when I turned on the radio one October evening in 1969, as I was setting the table, and heard that he’d died.

I used to wonder what would have happened to Jack if I’d been quicker to buy that plane ticket to Mexico. What if, by September, we’d moved to a village where it might have taken weeks for news about On the Road to reach us? Without Jack’s presence—for the interviews, the TV shows, the clamor of fascination with him as the messenger of a powerful idea that he seemed to embody so perfectly—would the uproar have died down much sooner? Would Jack have seen more attention paid to what he cared about most, the beauty in On the Road, and would that kind of fame have been more survivable?

“My work is found,” he’d recognized in l951, as he was starting a new book about his relationship with Neal called Visions of Cody that would be far more daring in its form and prose than the one he’d just finished, and even less likely to be published. “My work is found, my life is lost.” He wasn’t yet thirty.

At twenty-three, he’d had a vision of what his place in American literature could be. It was Labor Day, and the war in the Pacific had ended just the day before. As Jack walked through his neighborhood in Queens, families were celebrating in their backyards under a blue September sky, and he could smell the aroma of all the meat they were about to feast on. “All this American richness,” he’d mused afterward, “Not for my likes, never.” (Only in his notebooks did he express such feelings about being a Franco-American; he could never bring himself to talk about them with a friend.) That day, with everything so piercingly clear to him in that moment, he named himself a “half-American” in his notebook—and thought that with his outsider’s eyes, he would be able to see America better than others.