Amant Foundation/New Document

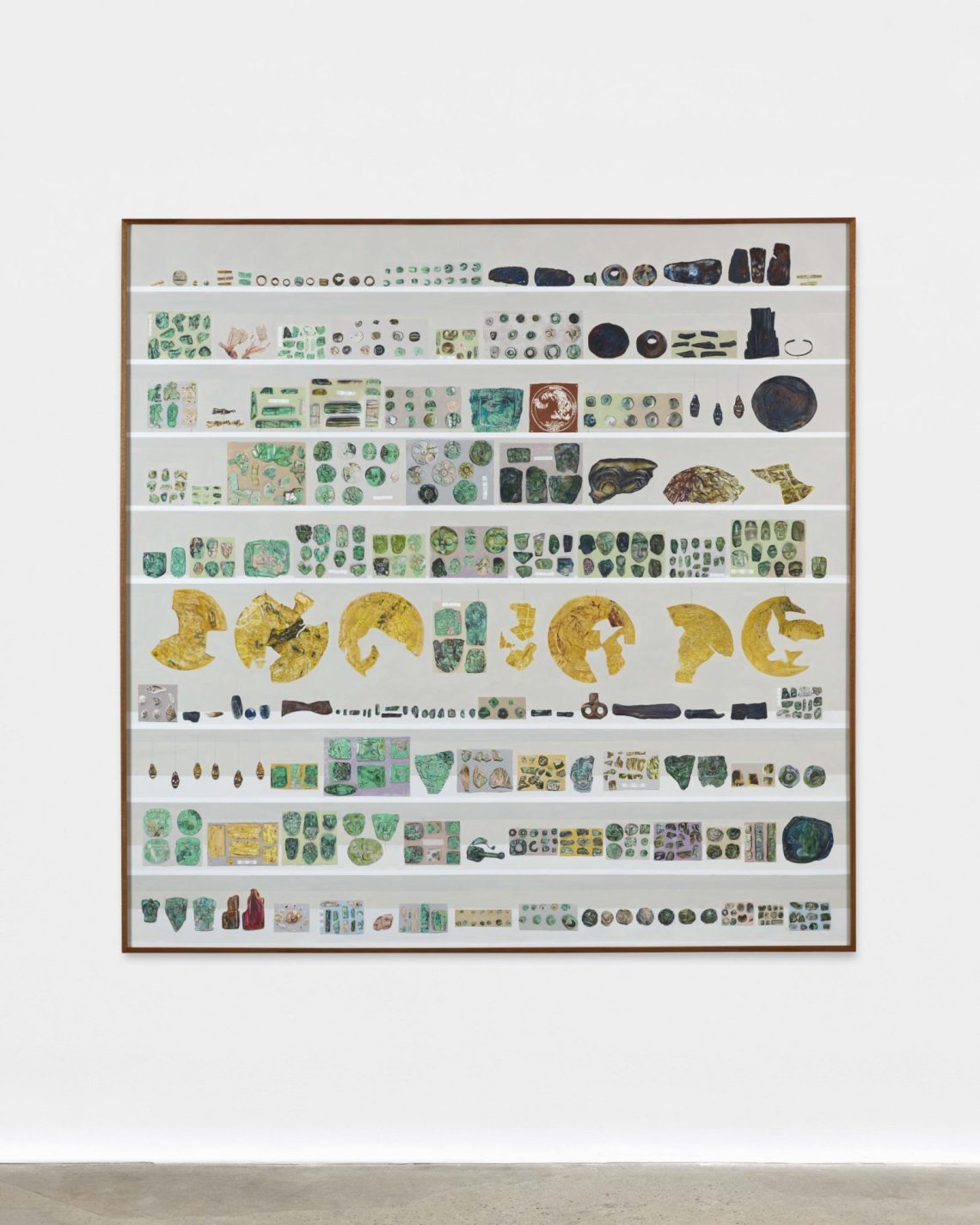

Gala Porras-Kim: (left to right) Proposal for the Reconstituting of Ritual Elements of the Sun Pyramid at Teotihuacan, 2019; Two Plain Stelas in the Looter Pit at the Top of the Sun Pyramid at Teotihuacan, 2019; All Earth Energy Sources are Known to Come from the Sun, 2019

When the American diplomat and archaeologist Edward Herbert Thompson purchased Hacienda Chichén for only three hundred pesos in 1894, he also acquired the ruins of Chichén Itzá, a Maya city on Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. A zealous student of antiquity who believed that Native monuments were traces of a vanished civilization, Thompson earned a reputation for outlandish claims after publishing a specious essay on the subject (“Atlantis Not a Myth”) in The Popular Science Monthly. It evoked a vast stone city “inhabited and viewed only by the iguana and centipede,” whose broad avenues were “now trodden only by the ignorant mestizo or simple Indian.” Once in possession of his own lost metropolis, Thompson quickly befriended the locals, learning their language and customs, sampling their cuisine, and, he claimed, earning membership in a clandestine society that appointed him guardian of their sacred drum. Over the next three decades, he explored and exploited the property at a gentlemanly pace, eager to unearth its secrets.

One of the estate’s most valuable features was a seemingly unremarkable limestone sinkhole, or cenote, filled with murky water. In Maya cosmology, such sites were seen as occasional residences of the gods, “portals between the earthly realm and the watery underworld,” as the archaeologist James Doyle writes, where pilgrims could leave offerings or perform sacrifices. The sacred cenote at Chichén Itzá had been devoted to Chaac, the deity of rain and thunder, and between 1904 and 1911 Thompson orchestrated a series of excavations to retrieve its contents, deploying pulleys, an orange-peel dredge, and even a Greek sponge diver. Various institutions and their affiliates provided funding. Among them was Charles Pickering Bowditch, a prominent patron of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University.

Although the Mexican government had outlawed the export of antiquities in 1897, Thompson managed to smuggle his extraordinary finds piecemeal to the United States in the luggage of friends and associates. While several jade and gold works were eventually returned to Mexico, most of the collection—nearly thirty thousand objects, including human remains—is still housed at the Peabody. During a 2019–2020 fellowship at the Radcliffe Institute of Advanced Study, the artist Gala Porras-Kim studied the museum’s extensive archive and probed the troubling origins of its hoard. Why had these offerings traveled nearly 3,500 miles from a sinkhole in Chichén Itzá to dry storage in Cambridge? And had anyone bothered to consult Chaac?

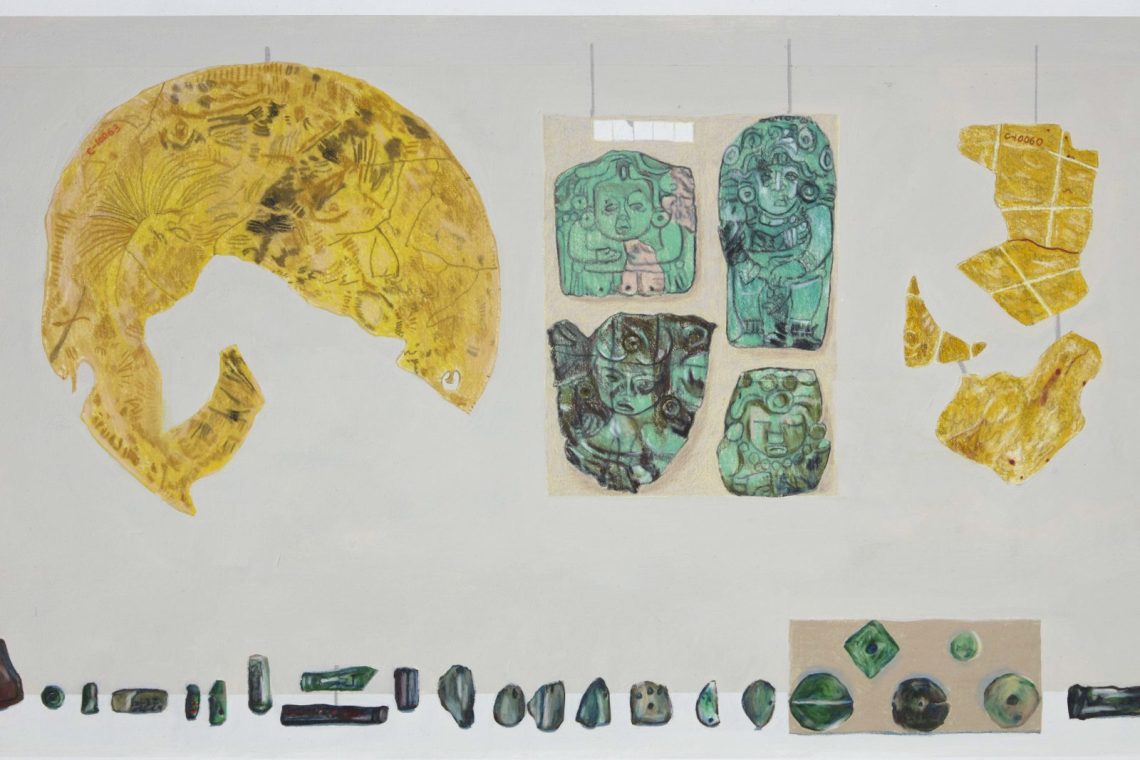

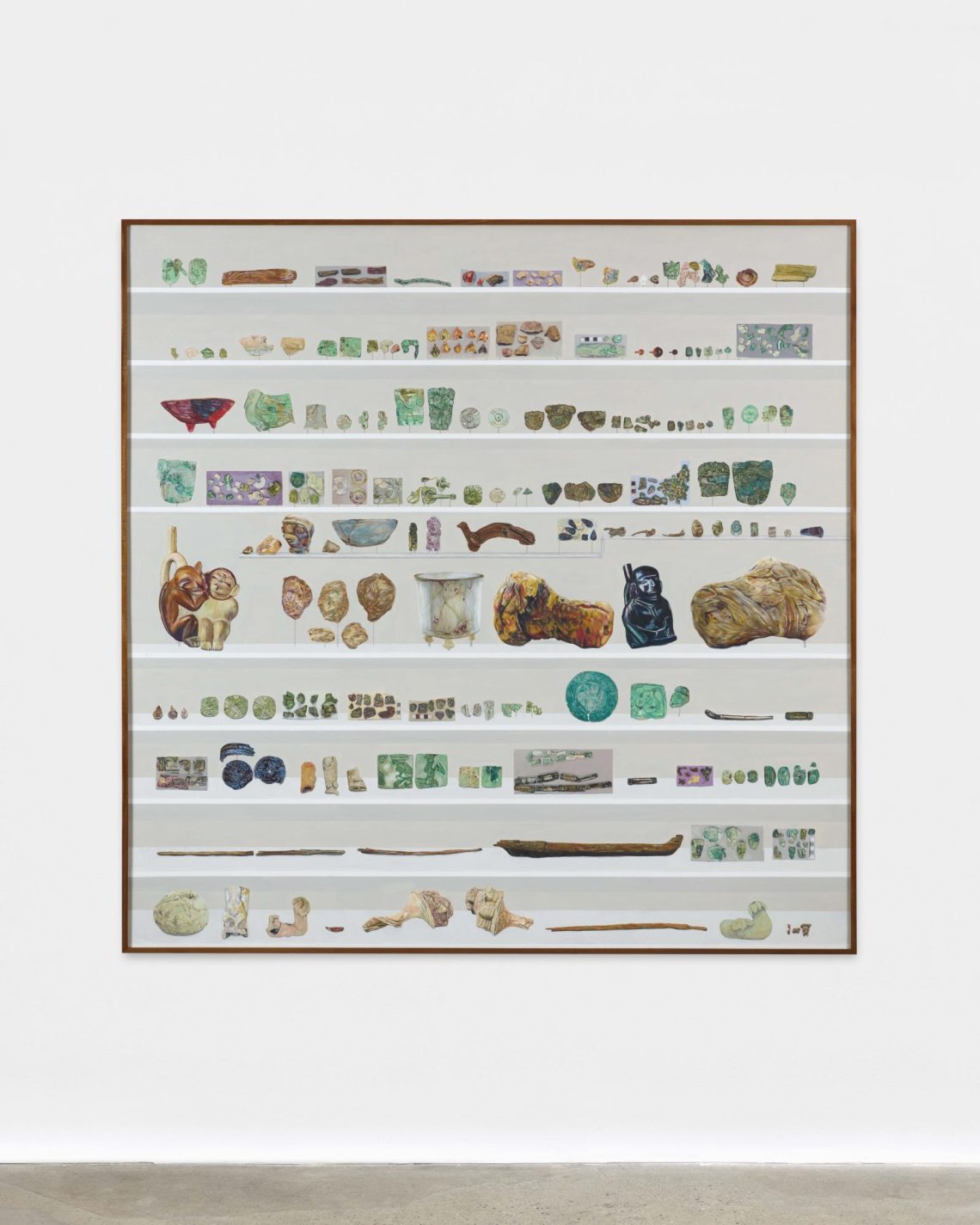

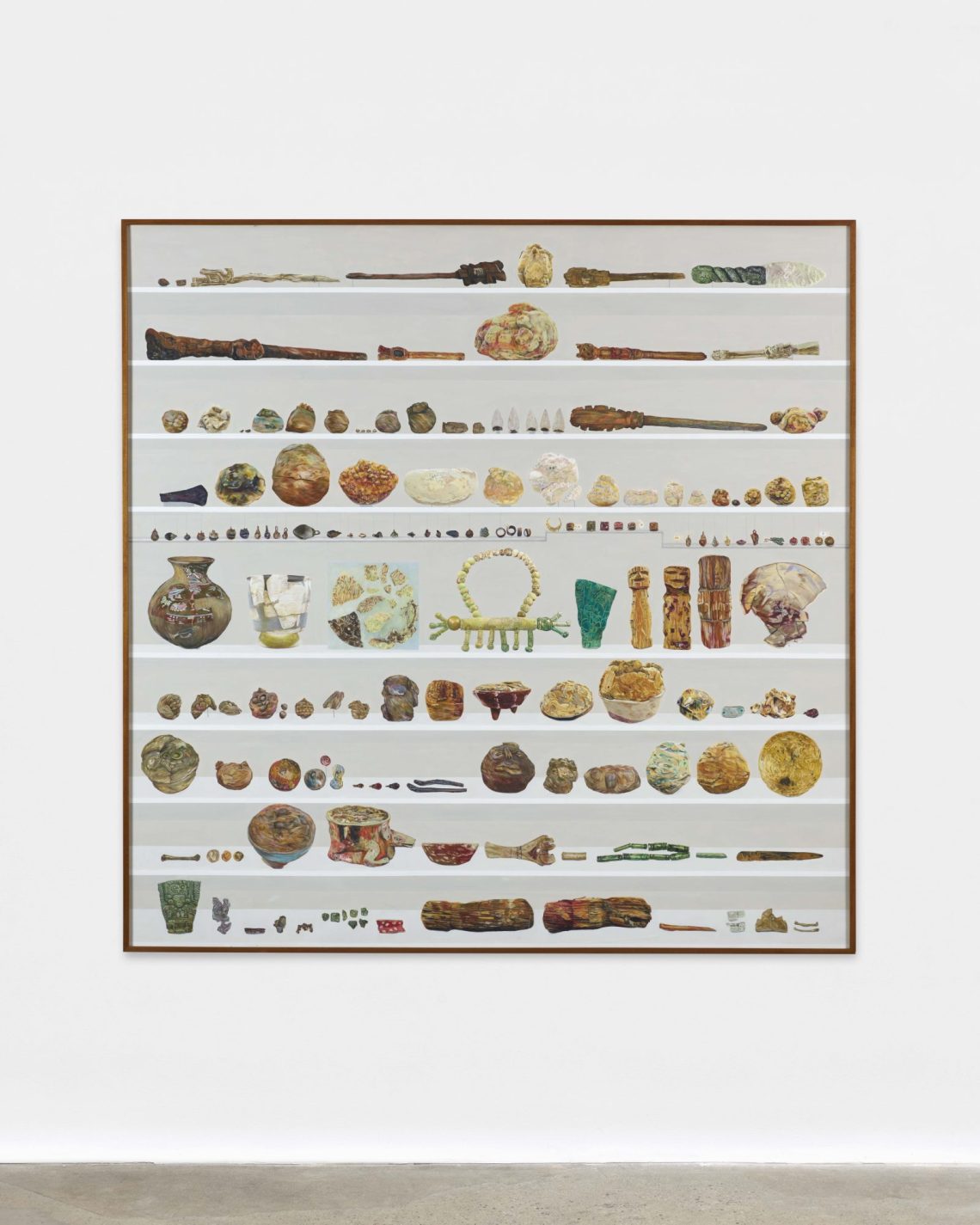

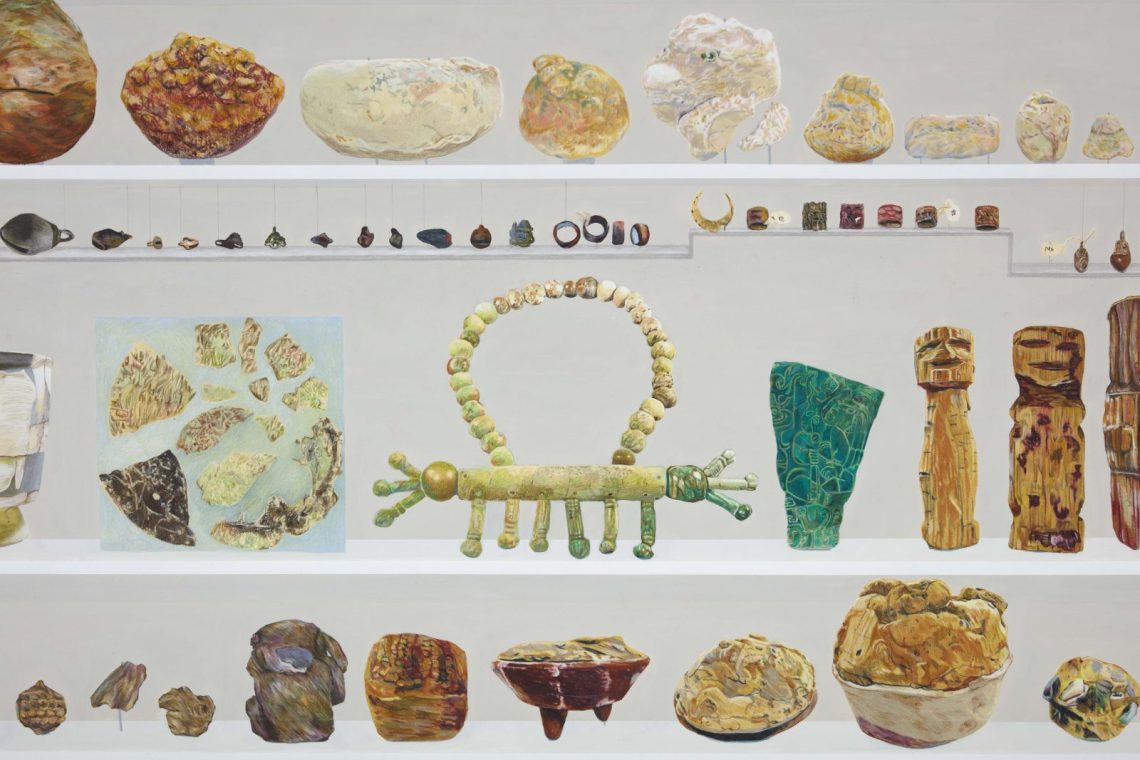

Earlier this year, Porras-Kim had her first solo exhibition in New York, “Precipitation for an Arid Landscape,” at Amant in East Williamsburg. It examined the lives of these objects, from their creation to their archaeological rediscovery and, later, their accession into private and public collections. The show’s centerpiece was a suite of mesmerizing trompe l’oeil panels depicting 5,249 Maya artifacts removed from the sacred cenote, arranged in orderly rows on sterile white shelves. (These are currently on view at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis; a selection of related works can be seen at the Radcliffe Institute.) Painstakingly rendering each object in colored pencil and Flashe paint, Porras-Kim also designed a physical space to simulate their original ritual setting, complete with a fragrant copal altar that disintegrated under a steady drip of rainwater in honor of Chaac.

Born in Bogotá, Colombia, in 1984, Porras-Kim has spent her career scrutinizing ethnographic collections around the world and working closely with scholars, curators, and museum administrators to untangle their histories of imperial violence and plunder. Her work follows in the tradition of artists like Fred Wilson and Andrea Fraser, who staged irreverent critical interventions at various museums throughout the 1990s and 2000s. But it also belongs to a new vanguard of institutional critique, whose practitioners include Carlos Motta, Maia Cruz Palileo, and Felipe Baeza. By creating works in direct response to specific museum and library holdings, these artists have begun to generate a counter-archive of images and invented artifacts that reflect on the ethics of collecting and the dislocation of cultural heritage under colonialism.

Expertly curated by Ruth Estévez and Adam Kleinman, “Precipitation for an Arid Landscape” exhibited Porras-Kim’s Peabody works alongside several other collaborative projects. Asymptote Towards an Ambiguous Horizon (2021) gathers twelve subtle, striking graphite drawings of Göbekli Tepe—a Neolithic archaeological site in Turkey that contains what is thought to be the world’s oldest temple—at different times of day and night. Constellations, sketched as they would have appeared twelve thousand years ago, encircled a metal model of the excavation, juxtaposing the apparatus of contemporary archaeology with the cyclical time of the ancients.

Advertisement

For Proposal for the Reconstituting of Ritual Elements for the Sun Pyramid at Teotihuacán (2019), Porras-Kim fabricated polyurethane replicas of two greenstone monoliths recently excavated from the summit of the famous Mexican temple. The work includes a letter to administrators at the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) in Mexico City, which warns that looting sacred sites might elicit divine retribution. Porras-Kim suggests that the institution “cover [its] bases with the forces greater than us who might care” by accepting her copies as official surrogates. She is polite but firm, demonstrating a playful epistolary flair that only reinforces her recommendations—which, it should be noted, went unheeded.

The show’s impressive namesake project, Precipitation for an Arid Landscape (2021), exhibited the panels of Maya objects and the copal altar beside a semi-circular “Documentation Room” of translucent corrugated plastic. Outfitted with a desk, a vitrine, a projector, a docket of scholarly publications, and scans of rarely seen primary-source documents, the space was both a map of the artist’s transit through the archives and an invitation for curious viewers to consider old and too often forgotten sins. (“There isn’t a Mexican who is honest,” the Mayanist Alfred Tozzer wrote to the Peabody’s director circa 1953 while scrupulously finagling the terms of repatriation; Harvard’s anthropology and archaeology library is named after him.) Black-and-white footage from the early 1960s documentary television series Expedition! presented a vacuum skimming the cenote floor, coughing up “beautiful, marvelous golden jewelry” and fragments of a human jawbone: a grotesque triumph of technology over nature, “scholarship” over the divine.

Porras-Kim’s panels transform the overstuffed vitrine, a staple of the ethnographic museum, into a powerful form of critical expression. The splendid objects seem to harmonize in aggregate: ceramic footed bowls heaped with copal, hammered gold platters, wooden scepters, anthropomorphic copper bells, coins, carved jade plaques and beads. Displayed at irregular and often impossible angles, they are organized in a rigorous, grid-like formation to maintain the illusion that some guiding intelligence holds them together. But as Porras-Kim revealed in a gallery talk, they are in fact arranged by accession number, a bureaucratic and ultimately arbitrary system of classification.

Unlike works of fine art, ethnographic artifacts were frequently labeled with accession numbers directly on their surfaces in pen or paint. Porras-Kim includes these defacements in her reproductions; by precisely detailing such “scholarly” barbarism, she emphasizes the grab-bag fecklessness that often masqueraded as anthropological objectivity. When an object’s surface area is too small to contain the entire number, a tiny tag is affixed. Porras-Kim sometimes treats the tag as a unique work of art, giving it pride of place on the shelf beside its accompanying object—a wry signal that the study and classification of these works are themselves the true subjects of her installation.

At one level, Porras-Kim’s work engages questions of stewardship that museums around the world are now confronting. Restitution debates have gained momentum as collections across Europe and the United States confront their complicity with colonial conquest. Provenance research, long the domain of scholars keen to authenticate and auction houses eager to establish pedigree, assumes a moral dimension: Who “owns” a work, and who decides the terms of ownership? Participants in this debate often rush to ask whether there are adequate facilities to safeguard these works in their countries of origin. Less often discussed is why certain aspects of objecthood are privileged over others. Should museums expand their scope of concern beyond material preservation and account for other factors, such as ritual efficacy? And even if the primary criterion for care is material integrity, what about works, such as textile fragments, that were better preserved underwater?

Moving beyond questions of legality and longevity, Porras-Kim advocates for respecting artifacts in accordance with the beliefs and intentions of their creators. One of her most poignant works is Leaving the Institution Through Cremation Is Easier than as a Result of a Deaccession Policy (2021), a persuasive argument for restoring privacy to museum “objects” that were never meant to be displayed. After the devastating 2018 fire at the National Museum of Brazil—which destroyed roughly 90 percent of the institution’s vast archive—Porras-Kim became an advocate for one of its most cherished holdings: Luzia, the oldest known human skeleton in the Americas. When Porras-Kim learned that the museum hoped to reconstruct Luzia’s skeleton from the remains of her remains, the artist wrote a letter to the director explaining how Luzia, a young woman at the time of her death, might not want to spend her afterlife as a tourist attraction: “I would like to propose incinerating the rest of her remains, because when you let go of the shape you think she should be as an object, she will return to her life as a corpse once again.”

Advertisement