“The year 1974 was a special odyssey for me,” the journalist and photographer Betty Medsger wrote in the introduction to her book Women at Work:

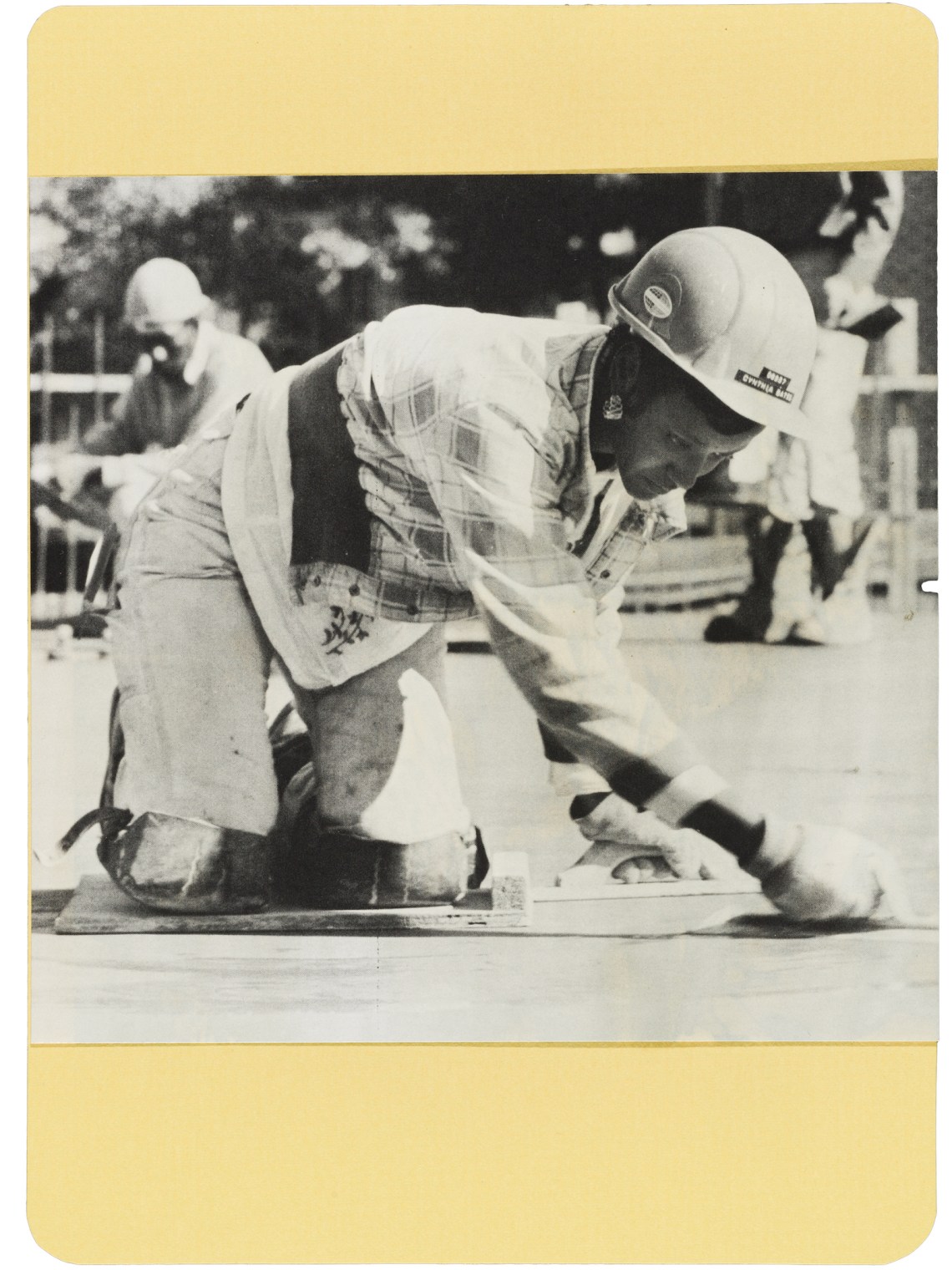

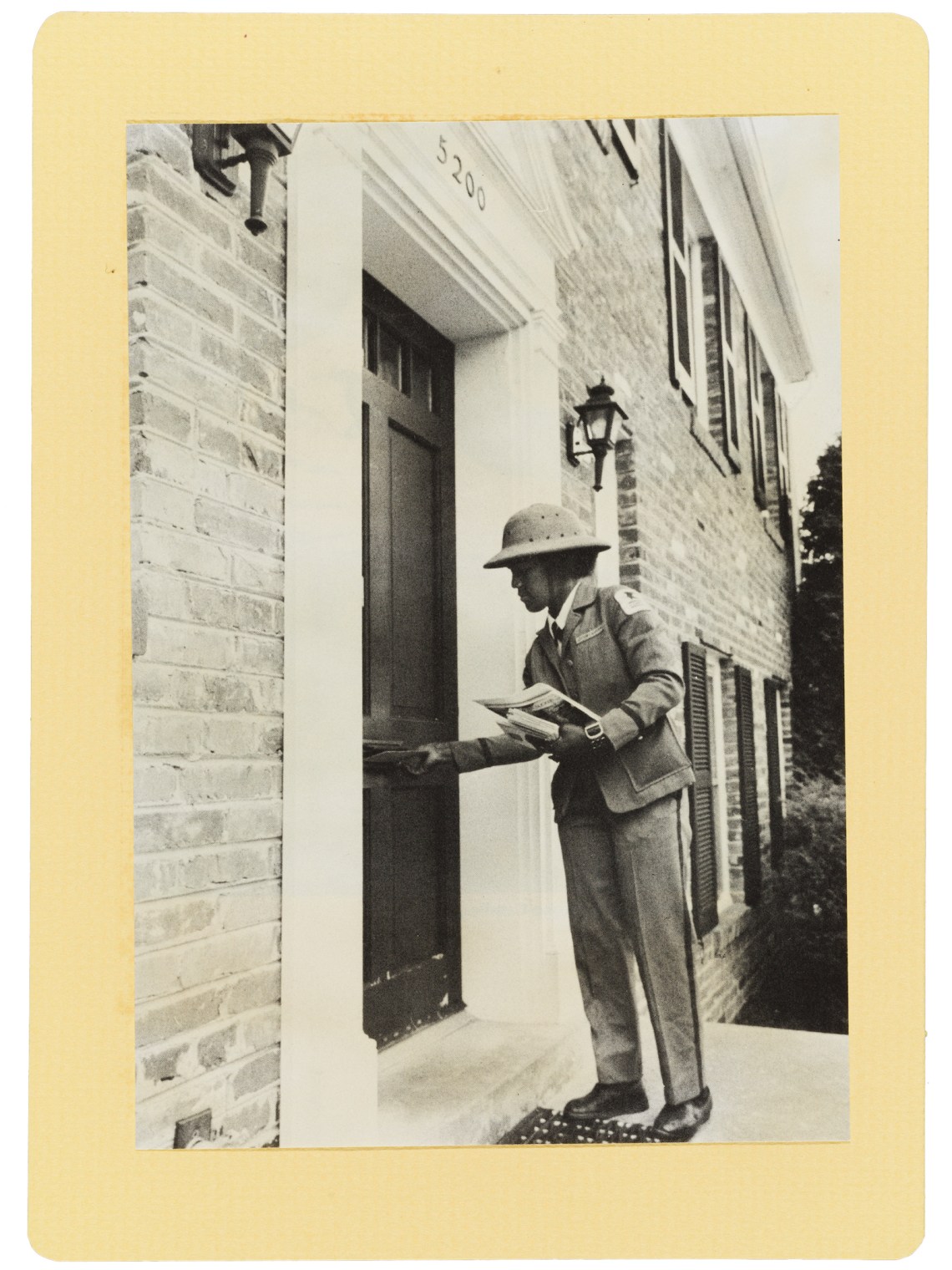

I traveled throughout the United States photographing and talking with women mining coal, running corporations, taking bosses’ letters, chopping down trees, stitching blue jeans and designing nuclear submarines. I did this because I wanted to document the very wide range of work being done by American women today. I wanted to convey real images of ourselves, rather than the stereotypes we regularly are fed by the mass media.*

Medsger was clear-eyed about the aims and limitations of her project. “I am not saying that every job you will see in Women at Work is a good job,” she wrote. “Indeed, there is some work represented here that you may feel no living creature should be doing. Rather, Women at Work is a statement of what exists. I hope it will help destroy any neatly divided stereotypes of ‘women’s work’ and ‘men’s work.’”

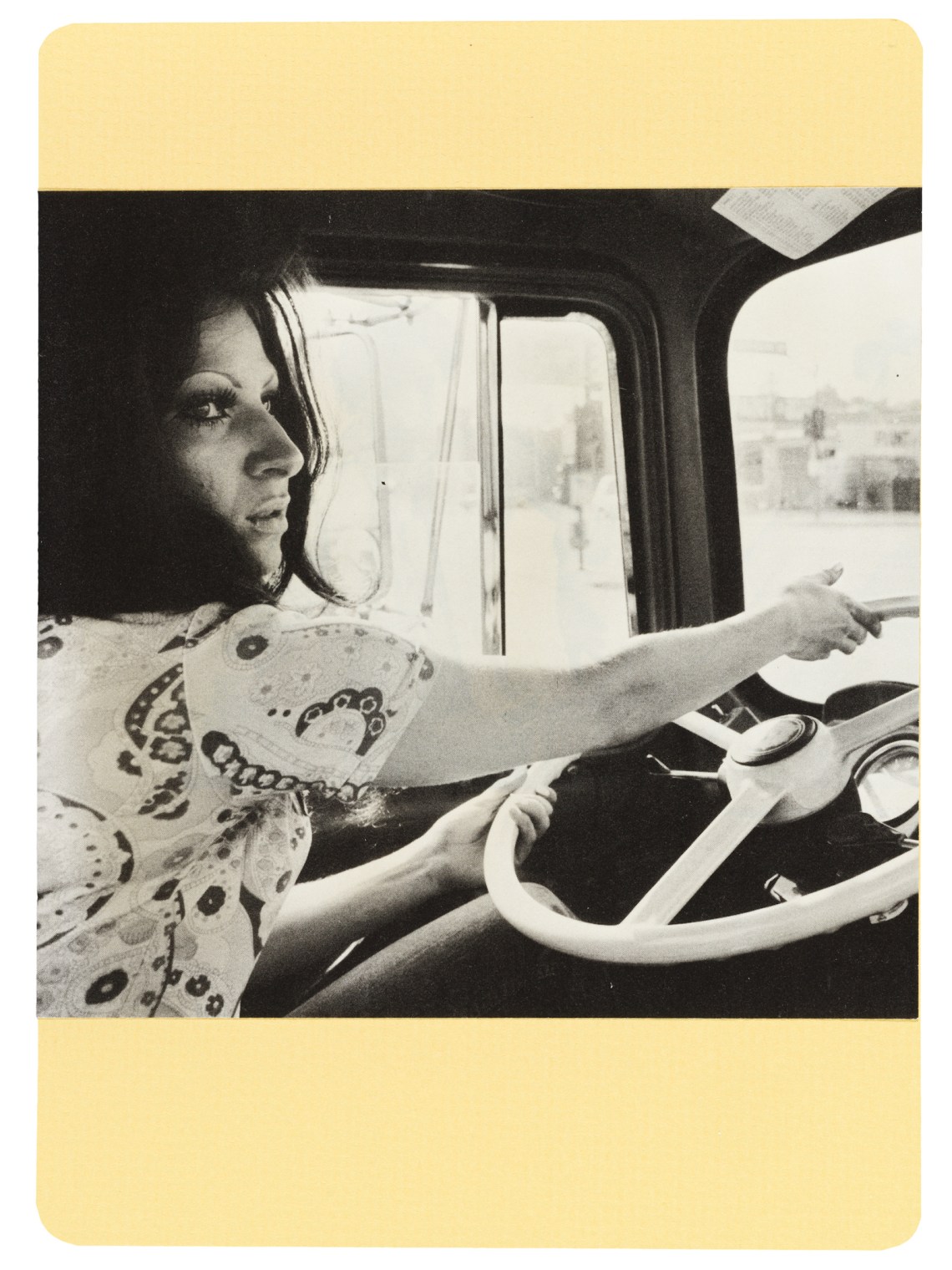

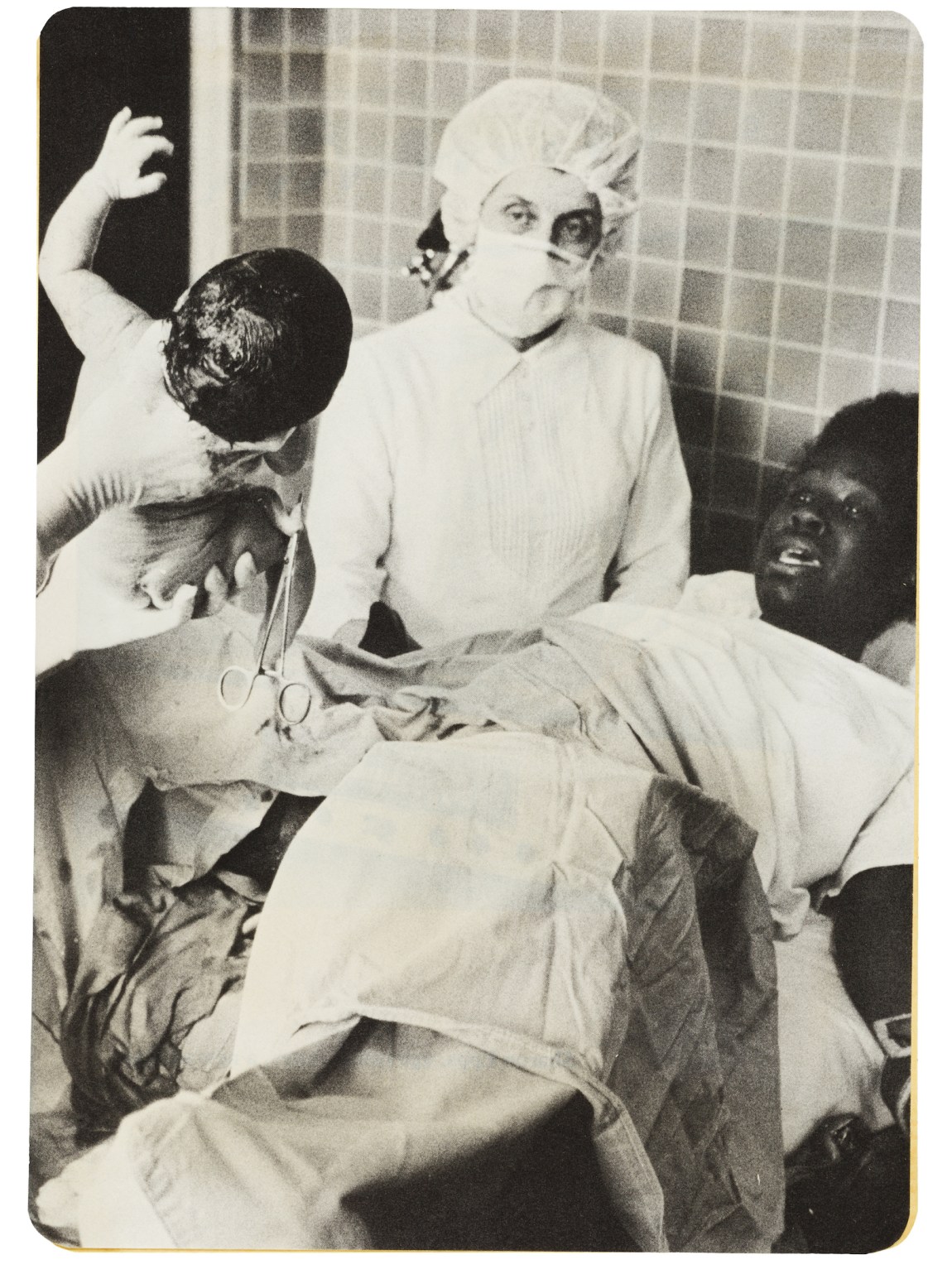

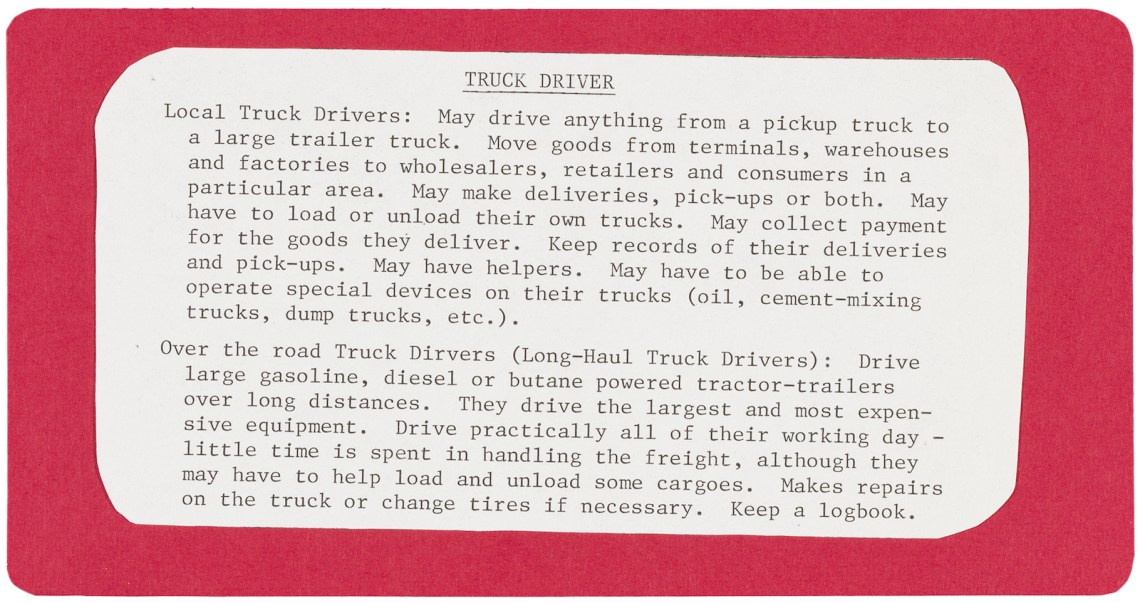

Her aims were explicitly feminist, and as she photographed her subjects she uncovered their perspectives on the movement. Rita Cox, a nineteen-year-old truck driver, told Medsger, “It’s hard when you meet guys socially. When they find out I’m a trucker, they say, ‘Oh, a women’s libber,’ and walk away.” She lied to men, she said, telling them she was a secretary or a hair stylist. Despite her disavowal of feminism, Cox admitted that “the women’s liberation movement probably has affected me, too. Some nights I work twelve hours and don’t get home ’til 5 a.m. And then a few hours later my boyfriend might come in and ask me to fix him a sandwich. Now I tell him…‘You have two hands, make your own sandwich.’” Medsger understood “work” broadly. Describing a photograph of a woman giving birth, she noted that the picture shows “not just the midwife, but also the mother, both very much at work.”

*

I found a worn copy of Women at Work somewhere between western Pennsylvania and Southern California in what I can only assume was a used bookstore. Once home, I sliced the book apart, carefully running my scissors through its pages, keeping the images intact while disconnecting them from their source. What’s leftover feels like a box of empty windows. I purchased another copy of the publication (this time online), which I have kept more or less intact. Even I—whom my partner, Luke, calls the book butcher—can be sentimental in this way.

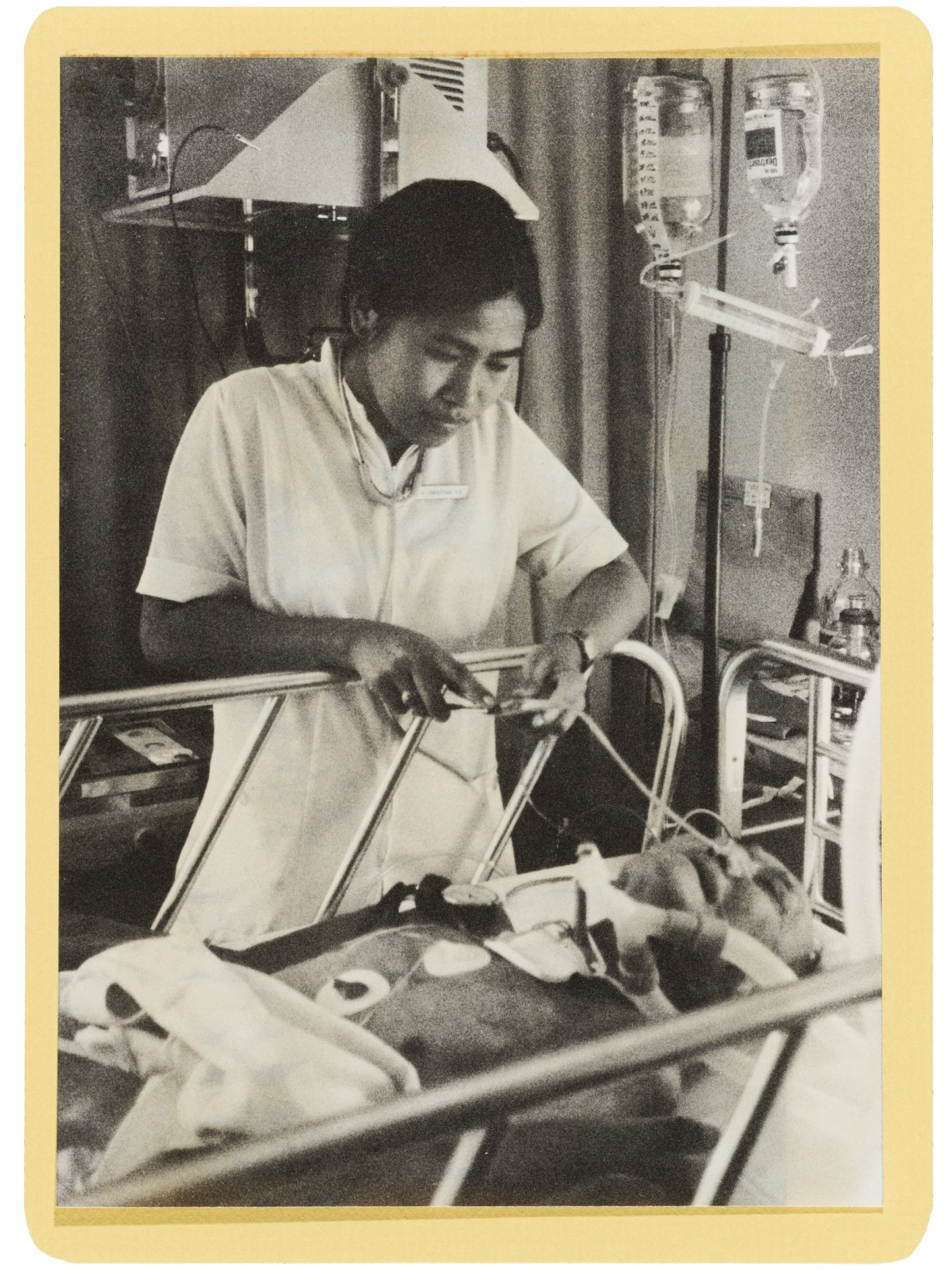

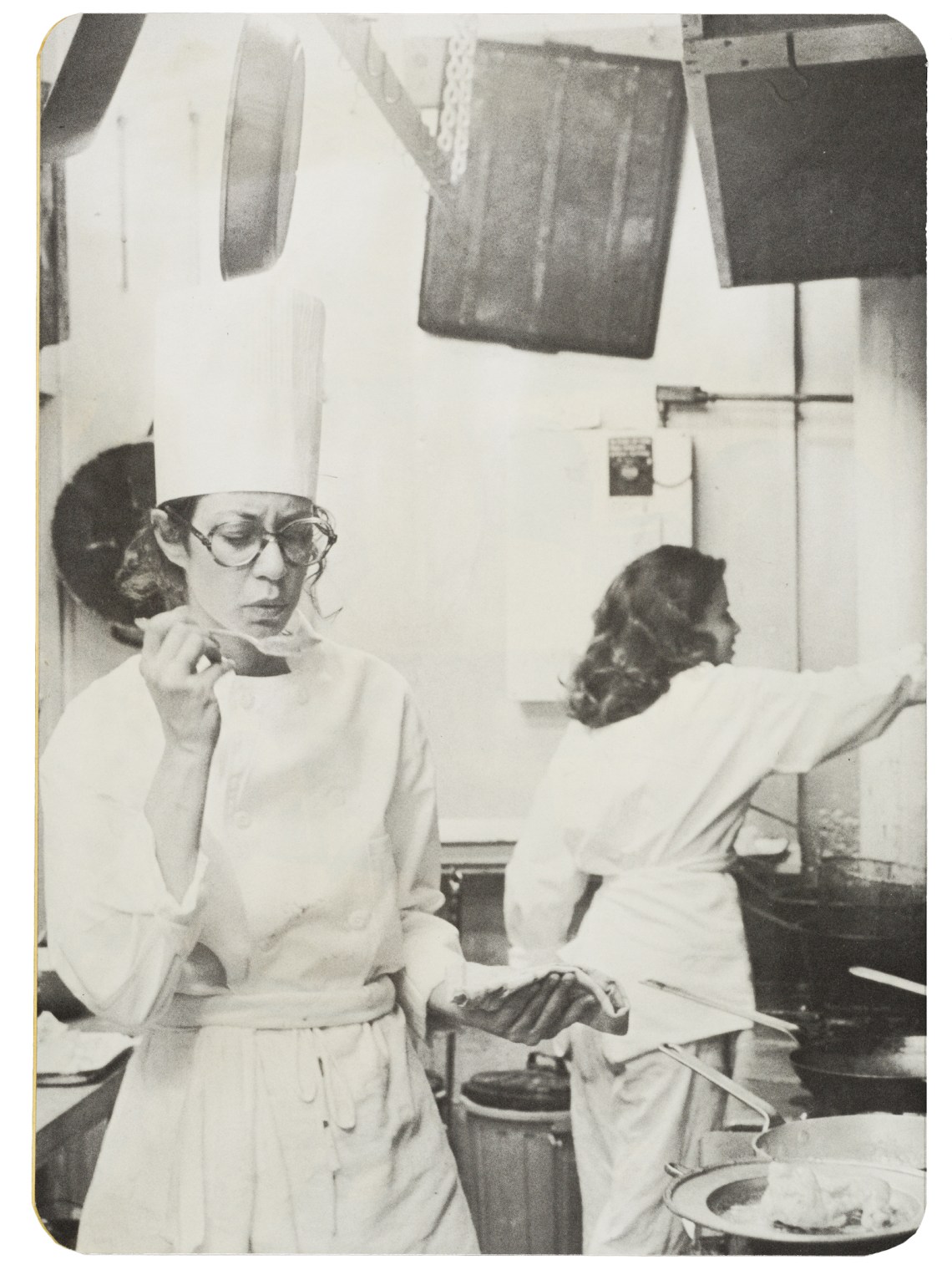

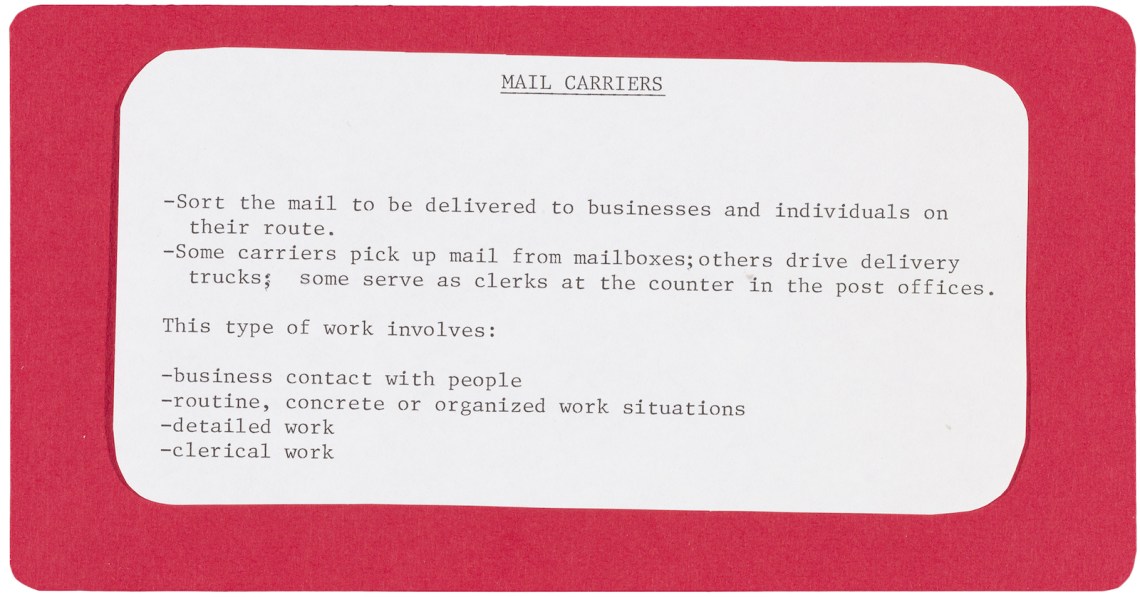

Years later I discovered a mirror image in the archive of Women In Transition, a domestic violence support and advocacy organization in Philadelphia: the Medsger book, cut apart, holding all the images I’d known. Someone at WIT (was it Annie, Susan, Irene? Roberta can’t recall) made a “job puzzle”—a three-part game for WIT clients with the Medsger photographs at its center. Each picture is held in place on yellow card stock by a snug laminated sleeve. They are photographic descriptions of women at work: Wilma Ann Jancuk, chemical engineer; Jenny Cirone, lifelong lobsterwoman; Norma Mann, steel company president; Rita Cox, nineteen-year-old truck driver; Nancy Umphers, nurse-midwife. There are 170 professions represented in Medsger’s images: orthodontist, florist, zookeeper, martial arts instructor, secretary, auto mechanic, mail carrier, air traffic controller, and so on. Some photographs are accompanied by narrative texts. Mostly the pictures are left to speak for themselves.

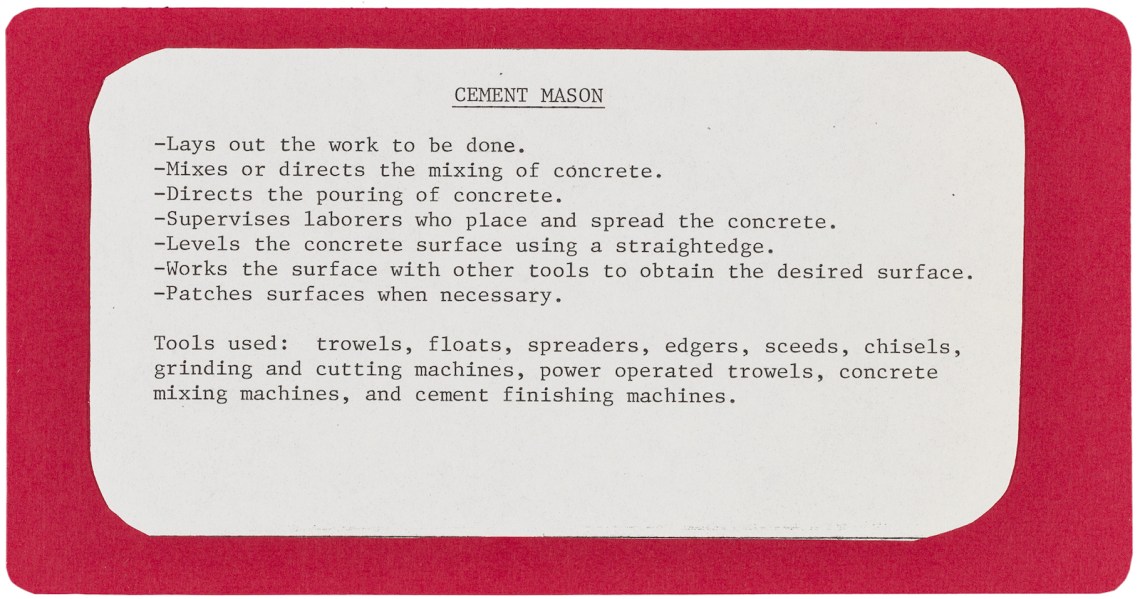

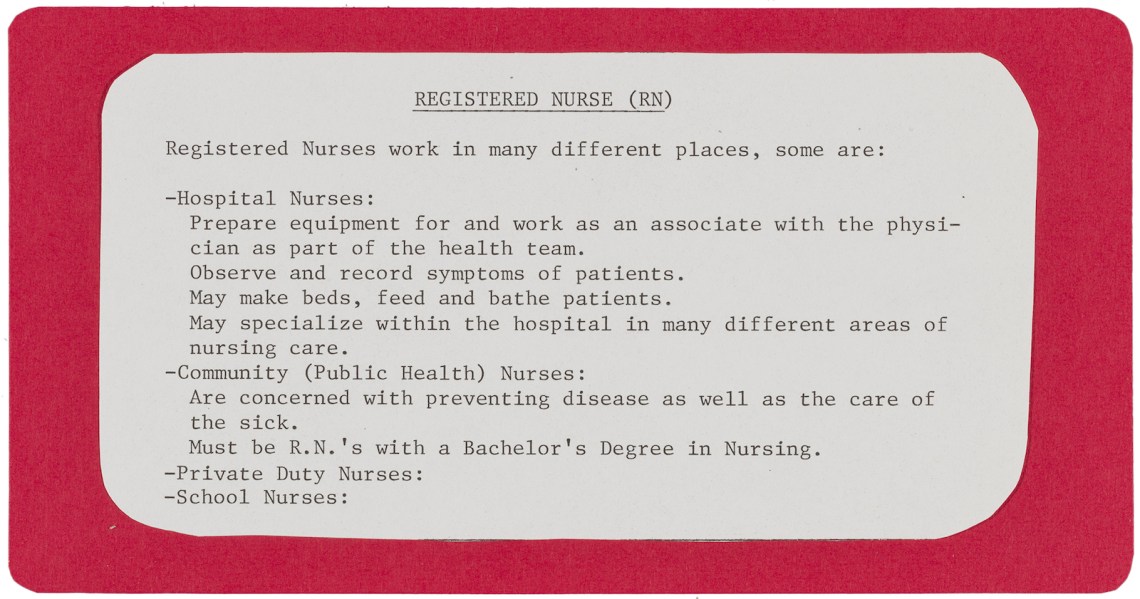

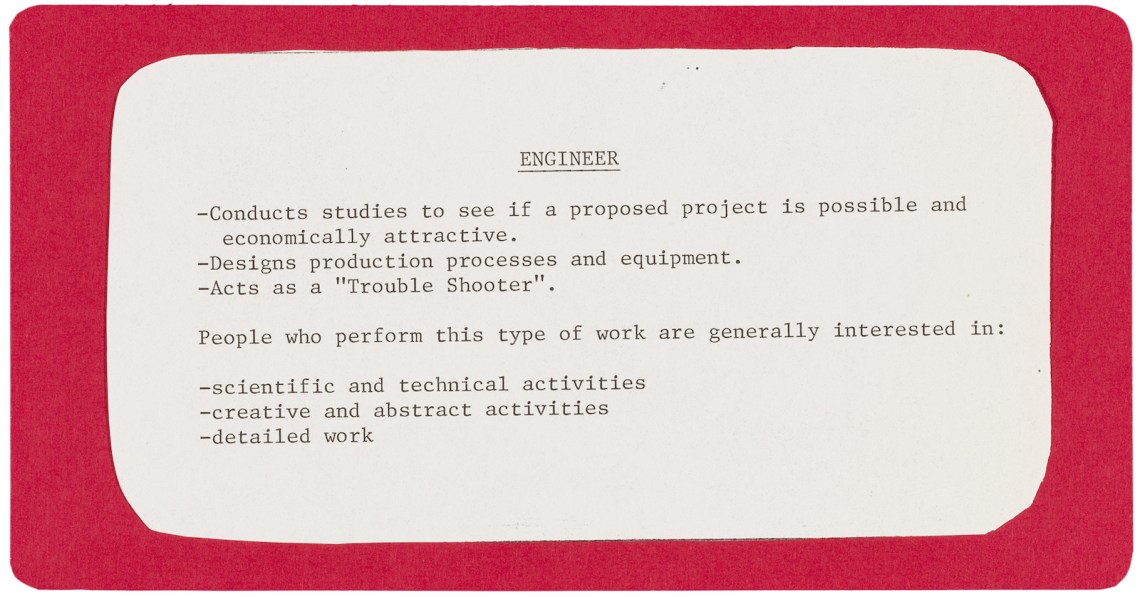

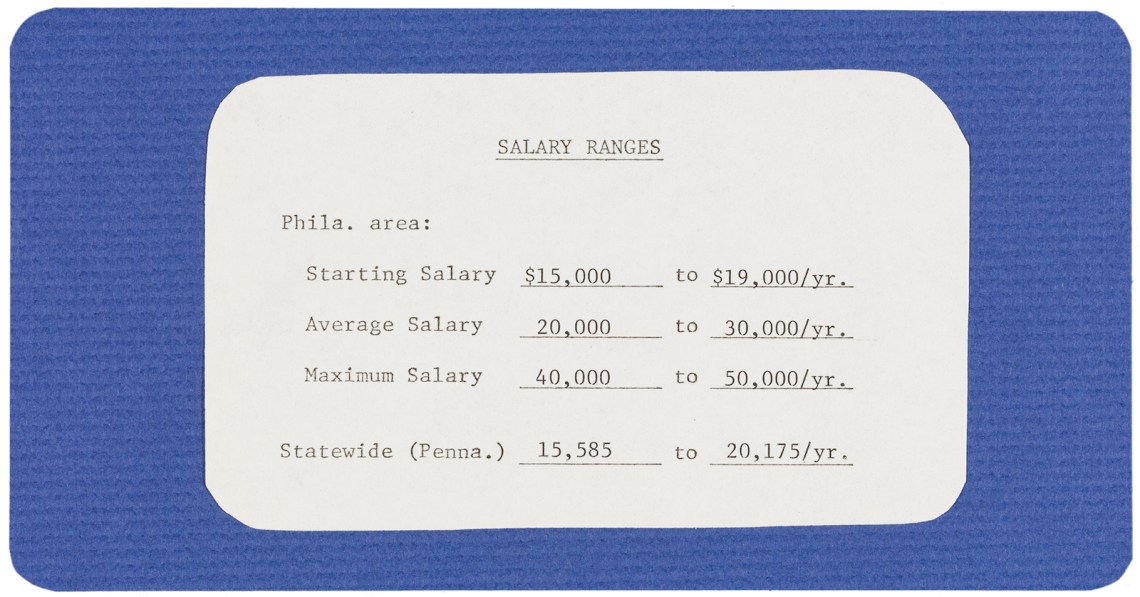

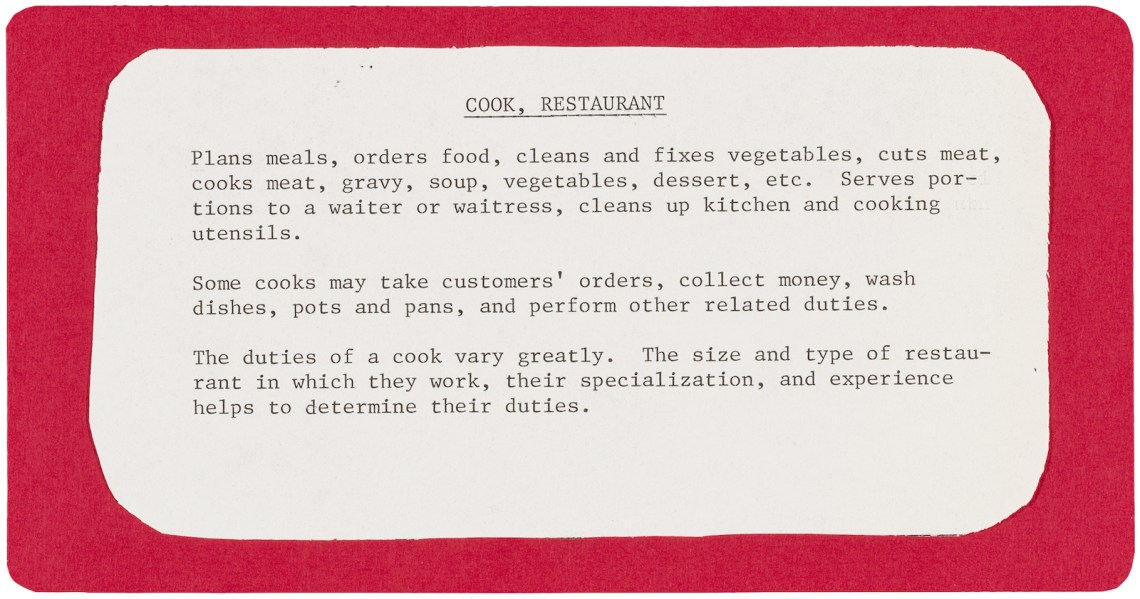

The other two components of the job puzzle—also in sleeves but half the size—are on red card stock (job description) and blue card stock (salary range and possible benefits). Clients played the game by matching up three pieces from the larger deck into a complete concordant set. The game is a response to the essential importance of financial independence for those escaping domestic violence, which is frequently contingent on victims’ financial dependence on their abusers.

I love this game. I love to see how photographs can be used provocatively and demonstratively at the same time. I love that photographs intended to teach women about their capacities were in fact used in just that way, if in a new place and for a new purpose. I love that play—guesswork, physical arrangement (bodies moving around each other in space)—was used as an intentional and effective counseling strategy.

To find this game, this job puzzle, in WIT’s archive was a revelation. In it I saw familiar pictures (that my hand had also excised, many years earlier) and familiar working methods (centering pictures as a learning tool). I work this way in the studio, matching and pairing like images, hoping to learn something or to surprise myself. I play this way with my children, too—or rather, I watch them play this way. It is already their prevailing instinct to read and aggregate pictures.

Advertisement

As for Medsger, I had always assumed that she was a photographer or photojournalist. In fact she is an investigative reporter who was instrumental in exposing COINTELPRO, the FBI’s unprecedented program of spying on students, academics, and antiwar and civil rights activists from the mid-1950s to the early 1970s. Women at Work—described on its cover as a “photographic documentary” and blurbed by Studs Terkel—is, as far as I can tell, her only pictorial undertaking (it came out in 1975, several years after her J. Edgar Hoover exposé), and it is often left off lists of her notable publications. And yet here it is, over and over again—in my studio, in a domestic violence support organization, on who knows how many shelves, and in who knows how many used bookstores. Pictures at work.