I first visited Iraq in October 2002, barely a year after the United States attacked Afghanistan in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. I went there as a photojournalist, invited by the government of Saddam Hussein to cover the presidential referendum in which, according to Iraqi officials, 100 percent of the population voted to extend his rule. It was my first experience working under the supervision of government minders, without freedom of movement, only allowed to cover pro-regime events. The US invasion already seemed inevitable after the passage that month of the joint resolution authorizing “use of military force against Iraq.”

Over the next two decades I covered conflicts big and small in Afghanistan, Haiti, Nepal, the former Soviet Union, Lebanon, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, but I spent more time working in Iraq than anywhere else. I was there to report “objectively” on the war, first for Newsday, then for The New York Times, then for a range of other American magazines. Last week I reflected in the Times on the experiences that made me call that objectivity into question: in 2003, early in the invasion, I spent eight days imprisoned by Saddam’s police in Abu Ghraib; three years later I saw firsthand how the US military co-opted former insurgent leaders to fight al-Qaida, turning enemies into allies; in 2014 I survived a helicopter crash during an Iraqi Army mission to rescue Yazidi civilians from ISIS.

As soon as the invasion began I heard a chorus of voices trying to define the narrative of the war: the US army’s made-for-TV press conferences from Qatar detailing military movements during the invasion’s first days; the increasingly bizarre press conferences by Saddam’s minister of information, Mohammed al-Sahaf, denying the US advance; Saddam’s own messages of resistance to the Iraqi people from hiding; and after the fall of Baghdad, statements about liberation and freedom issued by the US and the US-installed new Iraqi government while the city burned.

Later, in the aftermath of the invasion, I saw Baghdad fragment along ethnic lines and descend into chaos and violence, in contrast to the more optimistic official accounts. Over time traversing the city’s fault lines became extremely dangerous. For a while it was too risky to drive to the airport, and periodically we had to hunker down at the Times bureau rather than report on what was happening beyond the blast walls.

“The question for war photography,” Judith Butler wrote in Frames of War (2009), is “not only what it shows, but also how it shows what it shows.” During the Iraq War, they argue, “the phenomenon of embedded reporting came to the fore.” In exchange for “access to the war,” journalists agreed both “to report only from the perspective established by military and governmental authorities” and “not to make the mandating of perspective itself into a topic to be reported and discussed.” I remember weighting the pros and cons of such an arrangement. Sometimes embedding was the only way into parts of Iraq deemed too dangerous for outsiders, and I would agree, hoping that some unexpected situation would produce moments outside the military’s control. But such moments rarely happened.

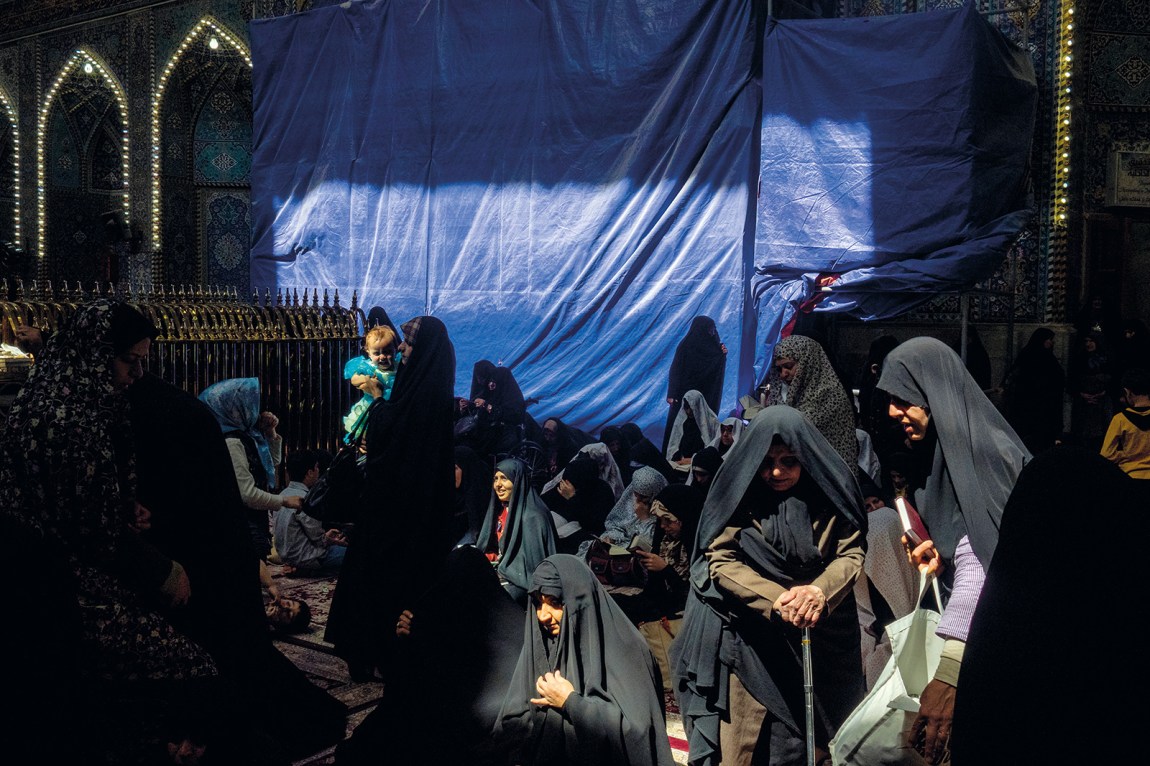

In my new book, Glad Tidings of Benevolence, I wanted to expose what Butler calls the “framing of the frame.” I juxtapose my photographs with texts: quotes from political and military figures, lists of killed Iraqi civilians and US coalition military personnel, an edited log of military operations, handbooks for soldiers, lyrics from Green Day’s “American Idiot,” verses of poetry by Dunya Mikhail and Sinan Antoon. Sometimes the texts and photographs speak to one another directly, and in other cases they collide, collude, confront one another: sinister, ironic code names of US Army operations, for instance, are paired with photos of wounded survivors. In editing the book, I hoped to depict human suffering in a way that will not only provoke new interpretations of the war but also make ethical demands of my audience, inspire them to move beyond distant empathy and act in direct solidarity with people whose lives have been upended by a conflict on the other side of the world.

My family is also part of this work, part of its frame. A decade ago, I fell in love and married an Iraqi-Kurdish woman—the author of the book’s epilogue. We now have a young daughter, Meyan, whom we often take on trips to Iraq to visit her grandparents and establish a bond with the country and history of her ancestors. We want part of her childhood rooted in this place that is hers, too.

Meyan’s favorite story takes place in the mountains between two rivers. The tyrant Zuhhak demands that two children are sacrificed each day, their brains fed to the hungry serpents growing out of his shoulders. I only edit one part of the story for her. In the version I was told growing up, a well-intentioned cabinet minister replaces one child a day with a sheep’s brain. For Meyan I sacrifice two sheep.

On Halloween a fire broke out in our apartment, barreling behind the walls through the three-story building, displacing all its residents. Weeks later, Meyan—trying, I think, to understand why we hadn’t returned home—asked me: Is the fire still burning? No, I explained. The bomberos put it out, but all our things are broken and we can’t go back.

I know my maternal grandmother only from stories. When I was told that she nursed her ten children in the seclusion of her room, I imagined her in a thousand hours of silence. I knew my paternal grandmother directly, as a feminist revolutionary who loved her public life. I am told that as a young mother, she didn’t care much for tending to small children, relying on wet nurses to free herself from that particular labor.

As a new mother after Meyan was born, I imagined myself suspended between these two women. Hypnotized by the coherence of my body and the baby’s when she nursed, sometimes all I could do was stare at her in the richness of our enclosure. When I wanted to step outside, I nursed while texting a fellow new mother. With my friend, I found the affirmation of our new reality: an intensity in the dark, the fetus emerged but still conjoined with its bearer.

My own mother became a mother in London, far from her home. That distance at once separated her from, and related her to, Kurdistan. I have experienced the violence in Kurdistan and Iraq from a distance—a distance that has bound me, too, to the place. I was born in 1988, three weeks before the smell of apples strangled Halabja. I can retrieve a clear image from that time, a scene that was narrated to me but that I neither witnessed nor saw in a photograph: my exhausted mother, caring for a newborn, while my father and dozens of London’s Kurds gathered in our living room, smoking, talking politics, planning the resistance.

Birth is a rupture. Where there was once unity, a space emerges between two separating bodies in the presence of one another. Since Meyan’s birth, a gap has grown between us—a gap that ties us to each other even as it relentlessly expands. Now three years old, I see her forming frames, improvising storylines, untying knots. Bright and wild, creative and precocious, she is full of expression. What can we create in the gap that binds us?

As expectations and oughts and ought-nots circumscribe her life, I want the gap to be a threshold. A space in which we reclaim and reimagine language, expanding the limits of what is legible, hearable, sayable. Where she can live with contradictions, free from the pressure to suppress, assimilate, and reconcile them. Where she can find recognition of her fears, vulnerabilities, and despair. Where she can play and fail. Where she can imagine, become, and be lost in the new.

Is the fire still burning? Resoundingly, yes. My grandmothers’ fires, my mother’s fire, the fire of the shadow I grew after birth. The fires of the children sacrificed for Zuhhak’s serpents. The napalm in Halabja still burns. Baghdad burns, Mosul burns, Sinjar burns, Speicher burns. Kurdistan’s civil war smolders silently in plain sight. Language burns, the US military as an arsonist. Fires still burn in the city squares, the squares that bound selves and others in rupture.

I can’t protect her from the fires, I can’t edit out the injustices. There is no truth that I abhor more violently. But in the binding gap between us, I commit to telling stories, speaking, and acting with her. About her, about me, about joy and loss, and about the fires—even the fires in our gap. —CS

Advertisement