The plays of Spain’s preeminent Golden Age dramatist, Lope de Vega, come across on the page as compressed and quick off the mark, agile in tracking actions and consequences, nimble in slipping from comedy to tragedy and back as needed. They make room for set pieces of all kinds, bantering wordplay, elegant verbal duets for lovers, satirical digression and philosophical quibbling, not to mention singing and festivity, without ever slackening the tension of their inexorable plotlines. In their structure they lay out a recognizable template for modern dramatic storytelling, while extending earlier traditions of balladry and folkloric chronicle. Working in the same era and in a mode parallel to what the Elizabethans were doing, but distilling a culture quite distinct, Lope embodies theatricality.

It is a theatricality that, locally at least, has mostly been relegated to that playhouse of the mind where works rarely or never publicly performed can be conjured up in disembodied stagings. New York has not been kind to Lope’s legacy, nor for that matter to that of his contemporaries Calderón and Tirso de Molina, who together produced as rich a body of playwriting as can be found anywhere. It was therefore good news that Theatre for a New Audience would be presenting Fuente Ovejuna. The choice of play was not surprising, since in Lope’s vast output—relatively few have been translated out of a surviving corpus numbering, at lowest estimate, well above three hundred—it is the piece that has been designated as his representative masterpiece, the only one likely to be encountered in general surveys of world drama or Renaissance literature.

This status came about arguably through a chance convergence, by which Lope’s recounting of the late-fifteenth-century uprising of an Andalusian village against an abusive military commander, first performed around 1612, was interpreted in later centuries as a resounding revolutionary text. Having already stirred subversive reactions in a Moscow production of the 1870s, to the chagrin of Tsarist police, the play enjoyed multiple productions in the Soviet Union and in Spain during the Civil War, and has been a perennial favorite of radically inclined directors from Erwin Piscator to Joan Littlewood.

Scholars tend to resist reading Fuente Ovejuna as a call to class revolt, casting Lope as a reliable upholder of the hierarchies within which he flourished. The play’s French translator Pierre Dupont characterizes it as “closer without a doubt to medieval and Christian political thought than to modern antifeudalism,” and many commentators stress that the murdered commander, who makes a practice of systematically raping the young women of the village, is also engaged in a factional struggle pitting a Portuguese contender against the rule of Isabella and Ferdinand. In a symmetry to which modern audiences tend to be immune, his violation of peasant honor mirrors his disloyalty to the land’s rightful rulers. His crime lies not in being a member of the ruling class but in recklessly fomenting social disorder.

Yet even allowing for what gets lost in political nuance after four hundred years, it would be a risky call to confidently assert what were Lope’s most inward convictions here or elsewhere. Any such determination would have to be distilled from the content of a preposterous number of plays (he claimed to have written 1,500), as well as thousands of sonnets both sacred and secular, a good number of novels and epic poems, treatises, hagiographies, letters—a multifarious body of work in which irony and contradiction abound—not to mention the details of a very busy life involving wives, mistresses (both before and after he took holy orders), offspring legitimate and otherwise, noblemen whom he served loyally, military service in the Great Armada expedition, prolonged exile from Castile following a conviction for libel, and at least one assassination attempt by the husband of one of his lovers. The irresistible desires and antagonisms that drive his plays would appear to have been amply nurtured by his own experience.

*

It had already been a long wait for Fuente Ovejuna when the new production was announced, and the wait was to prove even longer, so much so that this review could only be written after the show’s closing. After a few initial performances, recurring cases of Covid derailed most of the run, right up to the final weekend, when it was at last possible to catch it. One hopes that this barely seen production will not mark a solitary sighting of Lope; however uneven in some ways, it achieved a power that solidly affirmed the play’s enduring strength. The structure and pacing of Lope’s narrative art—the force of his confrontations and climaxes—could at last be experienced in the theater rather than imagined.

Advertisement

In bringing Lope to the stage the question of translation is unavoidable. Most versions of Fuente Ovejuna I have read are dutifully literal and no more, with the exception of Roy Campbell’s poetically ambitious attempt, published in the 1950s. TFANA selected the British poet Adrian Mitchell’s version, which enjoyed major success in London in 1989. Mitchell pares away the decorative fringes of the verse to achieve a spare, occasionally brutal effect that fully conveys the play’s stark structure. Inevitably he trims some undertones and nuances in the process. Compare Mitchell’s rendering of the passage in which the peasant Frondoso, protecting his beloved Laurencia from rape, threatens the Commander with a crossbow—“Let her go or I’ll be forced to/Aim at the red cross on your chest/And shoot your heart out”—with Campbell: “Most generous Comendador, let go/Of this poor girl, or else with your own bow/I shall transfix your body without sparing./Although I tremble at the cross you’re wearing!” Mitchell elides Frondoso’s unease in going up against the symbol of religious authority, making the shepherd’s sudden bold turn less wrenching than it is.

Campbell’s text has its pleasures—he is intent on bringing out the baroque colors and ornamentation of Lope’s language—but it is hard to envision the kind of acting that would be required to put it across. Mitchell’s bluntness keeps the focus on speech as aggressive action. Compressing rhetorical flights, he gives us the bare bones of the play’s movement in a way that matches the production’s skeletal design. Directed by Flordelino Lagundino, this staging blurred the line between modern and medieval, with automatic weapons and camo jackets interspersed with pikes and swords. On the Polonsky Shakespeare Center’s intimate stage, open on three sides, the violence of the narrative was brought home by constant rough incursions down the aisles and out again, as the commander or his henchmen invaded the peaceful pastoral scenes and dragged away their victims.

The total vulnerability of the villagers in the face of military overlords was made visible by the open spaces where their scenes played out. They had nowhere to run to, nothing to hide behind, and no weapons until Carlo Albán’s Frondoso, defending Laurencia, appropriates the commander’s crossbow and keeps him at bay with it. Given the theater’s close quarters, it was possible for a spectator to feel exposed to danger at such moments of threatened violence; accelerating steadily over the course of the play, they were calculated to instill a temptation to duck from an imagined arrow or sword thrust.

The play’s rhythms alternate between the relaxed interludes of village life, with its opportunities for courtship, music-making, and humorous debate, and the ominous interruptions from outside. Lope’s peasants are of course an idealized sort, and even the requisite clown of the company, Mengo, is philosophically disposed and ultimately as heroic as anyone. (Kenneth De Abrew reveled in this part, making the character’s evolution pivotal to the play.) The comic and romantic passages of the first half seemed muted in the performance I saw. Ideally those scenes should establish a mood of exuberant pleasure that would contrast all the more with the horrors of rape, corporal punishment, and torture that follow. The musical component was pleasant, but more excitement was called for in, for example, Laurencia’s robust ode of praise for the delights of rural cuisine—“a tortilla/The size of a cartwheel/With cupfuls of basil inside it…rabbit and cabbage/United with garlic and spices”—a speech that ideally ought to elicit some actual hunger.

Advertisement

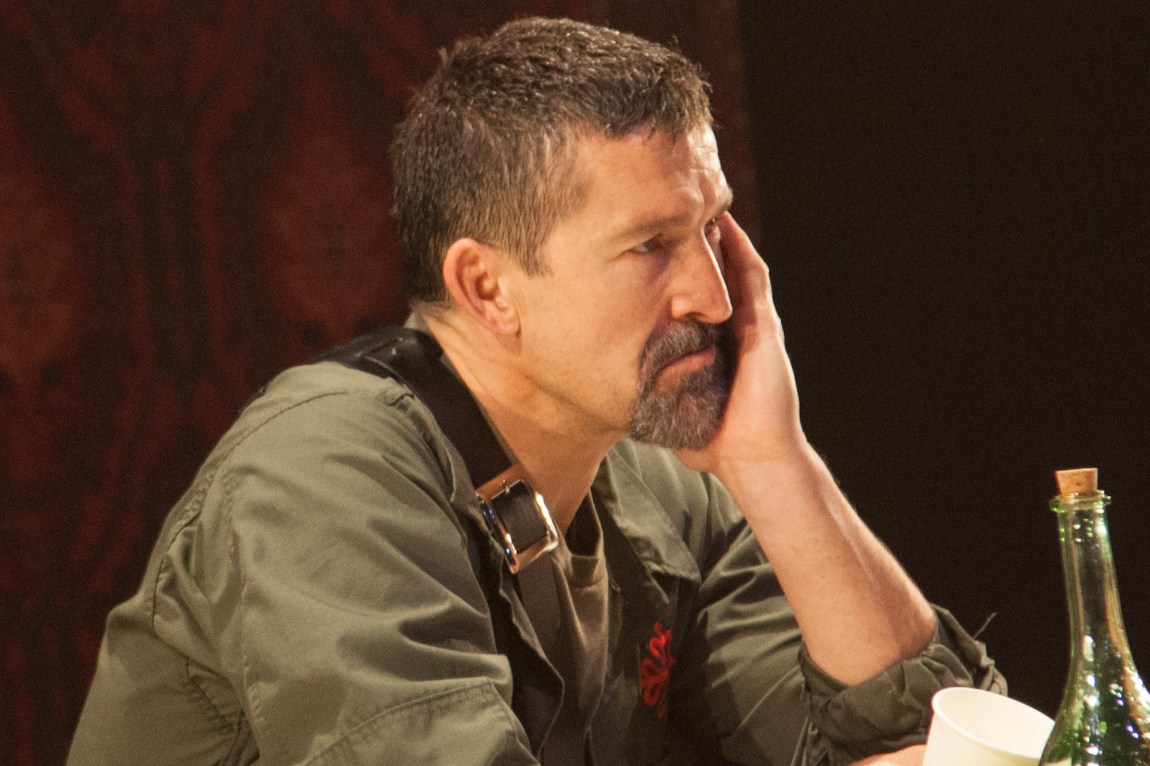

As it was, the first half was very much dominated by Jonathan Cake’s swaggering commander, shouting down all opponents, the very picture of overweening aristocratic contempt for underlings, with an undertone of cowardice beginning to show through as the peasants start to resist. The balance of energies shifts decisively when the commander intrudes on the wedding of Frondoso and Laurencia, arresting him and abducting her. Carmen Zilles did full justice to the play’s most important speech, when Laurencia, who has managed to escape the commander’s headquarters, upbraids the villagers for their submission to unjust authority: “You stood and goggled like cowardly shepherds/While the wolf ran off with your lamb…/Doesn’t my hair tell its own story?/Can you see the blood on my skirt?/Can you see the bruises/Where they clutched me?” (Lope’s text suggests that Laurencia has managed to avoid rape by resisting and fleeing, although the suggestion comes from her fiancé, who might be reluctant to acknowledge dishonor; Mitchell’s translation strongly implies otherwise.)

The speech unleashes a rage that leads immediately to the collective killing of the commander by the aroused villagers, staged very much in the spirit of a chaotic free-for-all, improvised by people untrained as warriors. It was at this moment that the play’s underlying ritual emotion became overwhelming. Laurencia’s exhortation, the instant coalescing of the village women into the driving force of the uprising, and the participation of the whole group in the spontaneous killing aroused a sense of wild excitement and unrestrained bloodlust circumscribed only by the symbolic limit of the stage, a limit barely maintained given the openness of the playing area.

Having permitted this spilling over of the most dangerous kind of feeling, Lope moves on to the tale’s memorably neat resolution. A crime has been committed that cannot be excused, even if the commander was on the wrong political side. Ferdinand and Isabella, their rule shored up by military victory, send a judge to the village to determine who to blame. The village elders agree on a policy: all those questioned, even under torture, when asked who killed the commander will answer only “Fuente Ovejuna.” Laurencia and Frondoso, alone on stage, listen to the offstage voices of their fellow villagers, screaming in pain but continuing to repeat: “Fuente Ovejuna.” In the final scene Queen Isabella is obliged to admit that since no individual can be convicted of the crime, and the entire village cannot be slaughtered, “we must pardon you”: thus what amounts to a legal technicality provides an acceptable outcome for villagers and monarchs alike. The repetition—which continues until the play’s very last line—has become the most purely effective dramatic device: title of play, name of village, and newly forged collective identity fused into a single insistent mantra.