For decades the zany underground comedies of the Gay Girls Riding Club were all but lost to history. Formed in the late 1950s and lasting until the 1980s, the GGRC was a private social club of Hollywood homosexuals whose activities included horseback riding in Griffith Park and holding dinners, notorious Halloween costume parties, and drag performances. Many of the club’s members worked in the entertainment industry, and in the early 1960s they started making their own amateur films: increasingly elaborate spoofs of popular American and European releases of the time, with the GGRC and their friends as the cast and crew. Recently their films have resurfaced in gorgeous digital restorations, thanks to the efforts of UCLA’s Film and Television Archive, the American Genre Film Archive, and the assiduous research of the queer film historian Elizabeth Purchell, who has chosen five of the group’s six extant films to screen on Metrograph’s streaming service for Pride Month.

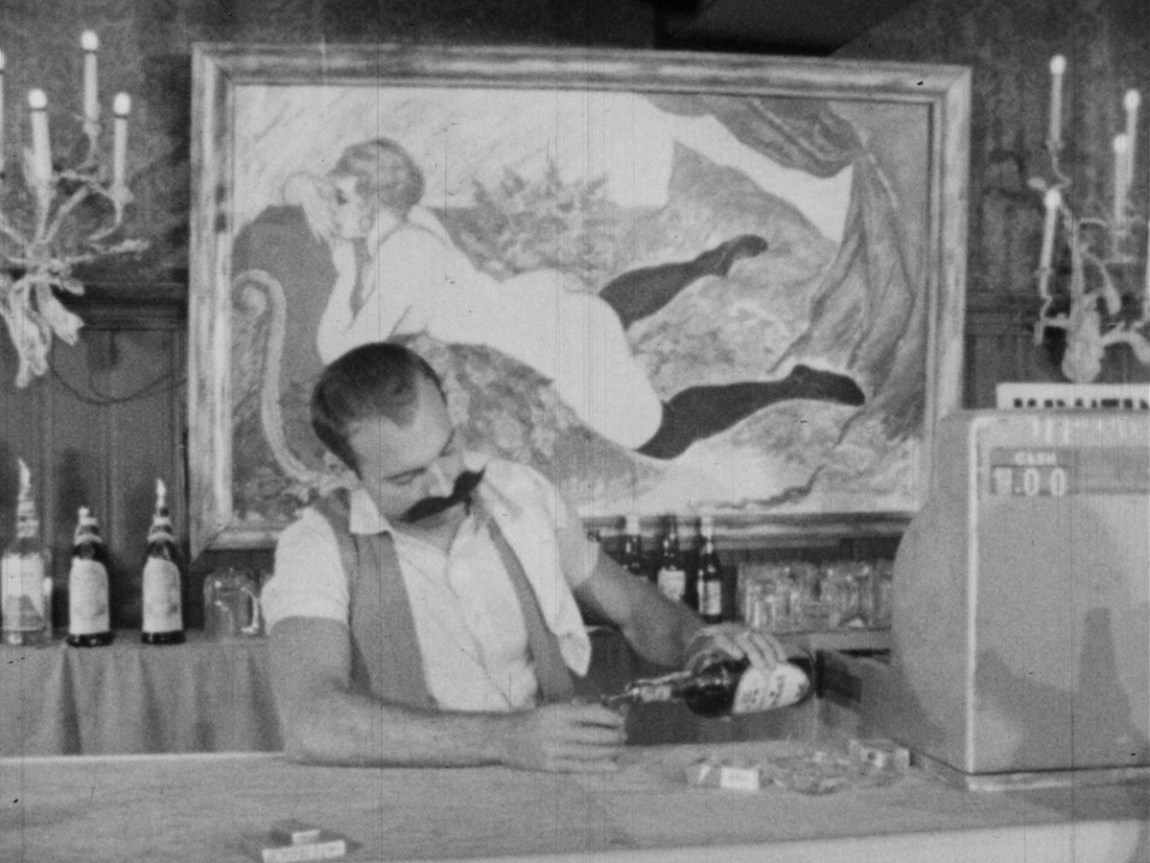

The Riding Club’s first efforts were shot without sound, on black-and-white 16mm film, with music and sound effects added later. Always on Sunday (1962) is a spoof of Jules Dassin’s Never on Sunday (1960); the club gathered, and filmed, weekly on Sundays. (Tragically, their Liz Taylor send-up Suddenly, Last Sunday has yet to be recovered.) Remembered today mostly for its bouncy, bouzouki-powered theme song, Dassin’s racy feature relates a love story between an uptight American professor and a fun-loving local prostitute in the Greek city of Piraeus. The GGRC’s eight-minute satire focuses on the latter character and her squad as they dance and flirt in a bar full of men. Without much redecoration, The Brownstone, then a gay watering hole in Hollywood, stands in for a portside taverna. The drag is loose and raw, with big messy wigs and teetering high heels, and the gag is that the hunky workingman and sailors the girls desperately try to solicit instead end up going home with one another. The film’s goofy home-movie quality has since allowed it to age into an accidental documentary, giving twenty-first century viewers a rare peek into a night at a pre-Stonewall hangout.

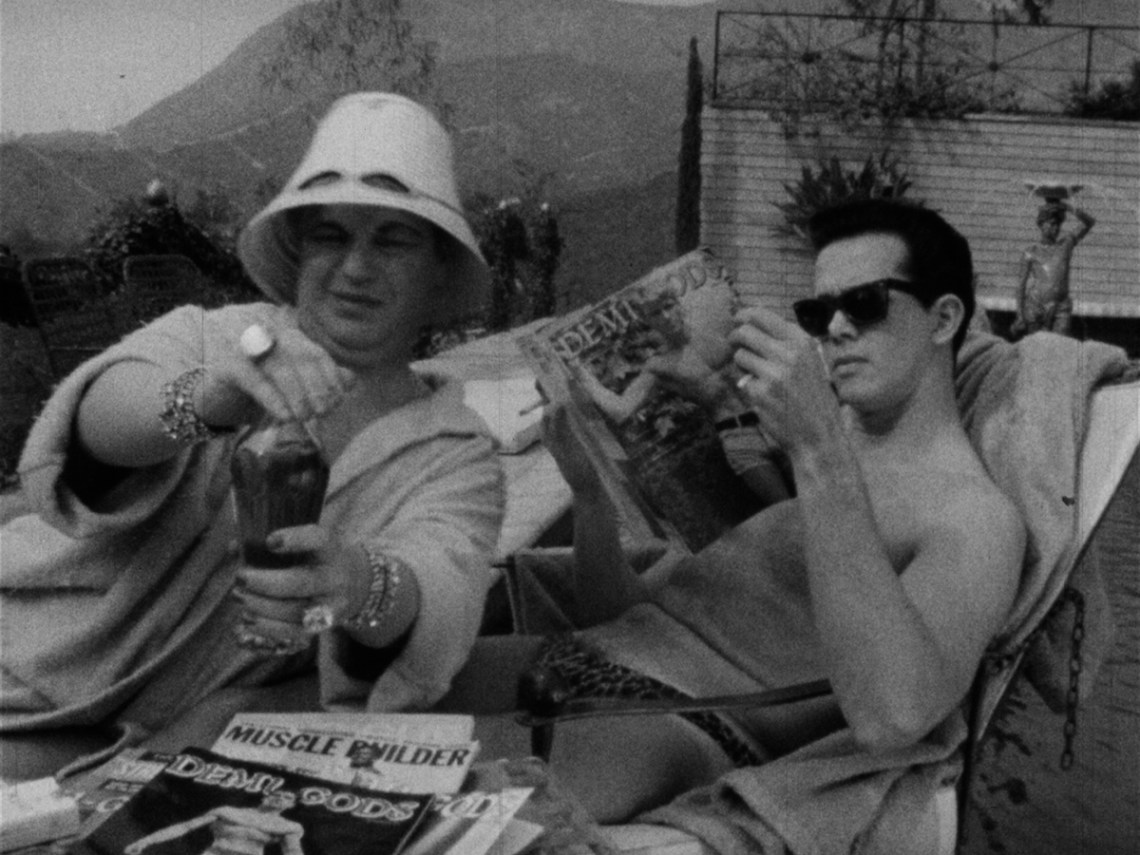

The gang assembled an even larger gaggle of feminine personae for The Roman Springs on Mrs. Stone (1963), a take-off of The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone (1961), Warner Brothers’ adaptation of the Tennessee Williams novel about an aging American actress who escapes to Italy and falls for a handsome gigolo. It inspires a range of sight gags: a maid’s costume reveals her shapely booty; a mirror cracks when it encounters Mrs. Stone’s middle-aged face; her paid companion Paulo ignores her as he thumbs through copies of physique mags like Muscle Builder and Demi Gods.

What Really Happened to Baby Jane (1963), the group’s signature achievement, was filmed about six months after the release of Robert Aldrich’s Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?; its opening minutes reference Joan Crawford’s infamous upstaging of Bette Davis at that year’s Academy Awards. Here the boys must have called in some favors. The film was shot inside someone’s lavish Los Angeles mansion, and one character is run over by a real Rolls Royce. The drag is rich and deliriously silly, the physical reads of Davis and Crawford’s characters and costumes so precise that one imagines the filmmakers and actors spent innumerable hours at the cinema studying the material. Or perhaps they had a bootleg screenplay: one of the most remarkable aspects of What Really Happened to Baby Jane is the use of several props from the original film, including one of the iconic Baby Jane Hudson dolls. It’s a fitting emblem for the uncanniness of physical imitation that drag exploits, as if the filmmakers wanted not merely to parody the original movie but to inhabit it in a form of worship.

How those props got there remains a mystery. As Purchell notes in interviews, little is known about the club’s members, few of whom have been identified; the earlier films’ credits mention only drag pseudonyms. All the extant movies were directed by a television production assistant named Ray Harrison, who listed himself as Connie B. DeMille. Some were lensed by James Crabe, who went on to become a successful cinematographer for films such as Rocky and The Karate Kid.

Advertisement

In their own day, the Gay Girls Riding Club became a notable presence in the burgeoning lavender demimonde. Having first screened at private events, their films started showing regularly on a loose circuit of art cinemas that catered to the counterculture. This was a time when the moniker underground film served as a potent code word for art, porn, and camp simultaneously, when softcore all-male posing-strap movies might play on a bill alongside Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising or Andy Warhol’s My Hustler. What Really Happened to Baby Jane was a particular hit, though it was listed sub rosa in ads as a “classic GGRC Gothic satire,” perhaps to avoid lawsuits—testimony to the healthy word-of-mouth reputation the group must have had among queer audiences.

After the half-hour Baby Jane, the GGRC produced a full-on featurette with the forty-five minute Spy on the Fly (1967), an action-packed James Bond spoof. Forced to go undercover as a woman and sent on a mission to Northern California, Agent 0069 dances the watusi with a go-go boy at a San Francisco nightspot and ends up in a shootout in a Chinatown opium den. Their most ambitious production—their only talkie—was also their last: All About Alice (1972), a riff on Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s All About Eve. Shot in color with synchronized sound, and featuring an original soundtrack complete with a catchy theme song, at sixty-eight minutes it’s the closest they got to making a true feature. In its own era, one imagines that it would have felt out-of-touch. An extended Bette Davis impression, no matter how well-done, must have seemed hoary alongside the sharp political satire of The Cockettes or the proto-punk anarchy of Pink Flamingos.

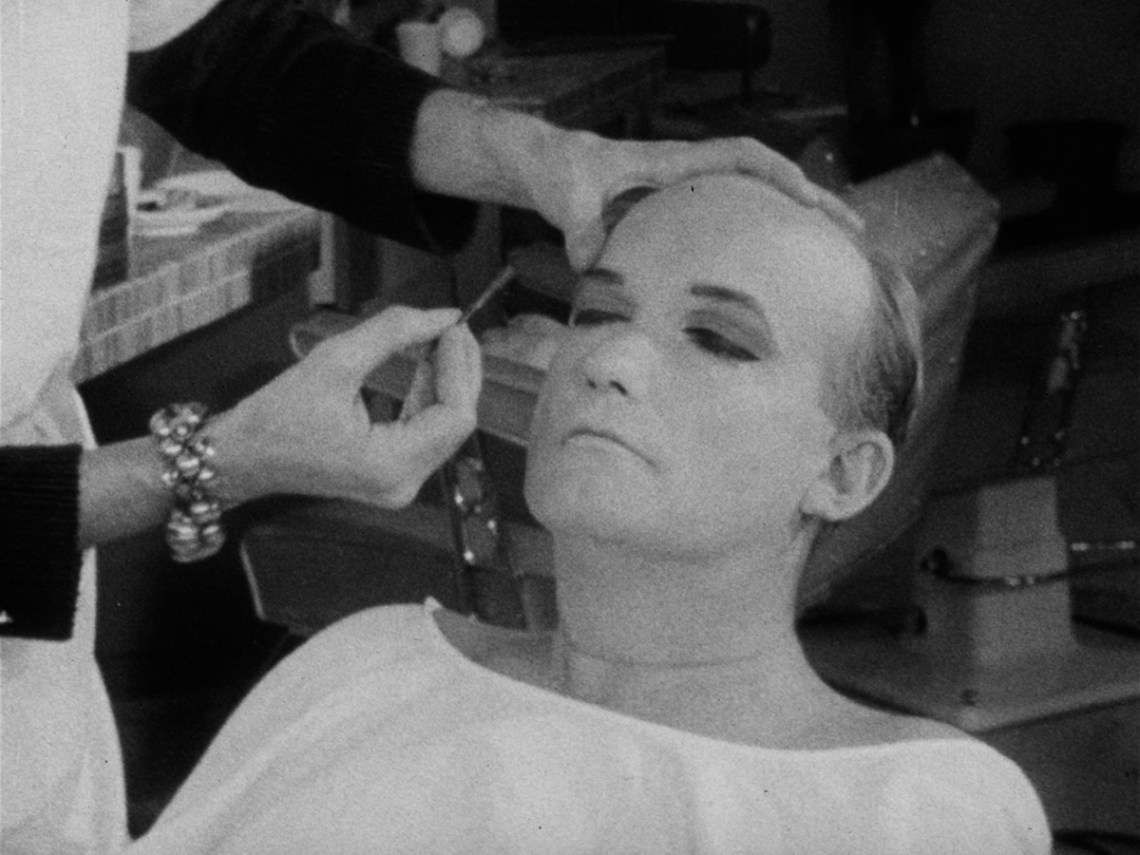

But All About Alice is also their most affecting work, less a satire than a sincere camp remake. With sound, the performances bring a nuance that’s missing from the earlier productions. Most engaging is the actor Christopher Jarman Morley, here credited as Jarman Christopher, who plays the Eve Harrington character, Alice Barrington. In later years Morley made a career playing cross-dressing bit parts in movies and TV; he is perhaps best remembered for his role as a brutally slaughtered transvestite in the violent cop picture Freebie and the Bean (1974), often cited as one of the most transphobic moments in Hollywood history.

All the more wonderful, then, to see Morley at his best in All About Alice. Here he mostly avoids the broad tropes of female impersonation and plays the character with a tender, dramatic subtlety. Mankiewicz’s film—about a young fan who maneuvers her way into the life of an older Broadway star—is not only a camp classic but also a story of becoming through desire and emulation. The Gay Girls Riding Club themselves rode this arc, moving from rough knock-offs to finely tuned simulations, pushing and expanding underground film until it apotheosized into the mainstream.