A large part of the work of writing is inarticulable. Writers who can explain what they’re doing while they are doing it, the ideological aspirations that govern their work in progress—these writers are alien to me. The process more familiar to me is witchier, an optimistic ignorance sustained on occasional gifts from the void. Donald Barthelme puts it this way:

The not-knowing is crucial to art, is what permits art to be made. Without the scanning process engendered by not-knowing, without the possibility of having the mind move in unanticipated directions, there would be no invention.

Toni Morrison puts it another way:

Because I am open and available, the universe—the idea—comes to me…. It’s that being open—not scratching for it, not digging for it, not constructing something but being open to the situation and trusting that what you don’t know will be available to you. It is bigger than your overt consciousness or your intelligence or even your gifts; it is out there somewhere and you have to let it in.

I remember my encounters with writers who address that liminality, writers who are otherwise critical and generous, who are necessarily prone to the compulsion to describe, and who, when asked about their process, offer no answers and focus instead on the preverbal gloam of how it felt. In her essay “Uses of the Erotic” (1978), Audre Lorde acknowledges the magic rooted in the practice of being awake to pleasure and to one’s capacity for softness. She writes about the North Star of making things, making love, making art—the visceral knowledge of it feels good to me. This practice is rigorous, she argues, because it requires a dogged self-maintenance that defies the hardness we learn as self-protection. She is writing about armor and earnestness:

We have attempted to separate the spiritual and the erotic, thereby reducing the spiritual to a world of flattened affect, a world of the ascetic who aspires to feel nothing. But nothing is farther from the truth. For the ascetic position is one of the highest fear, the gravest immobility. The severe abstinence of the ascetic becomes the ruling obsession. And it is one not of self-discipline but of self-abnegation.

Lorde gave me better language for the primal bedrock of artmaking: permission to embrace abundance, instruction on how to be open and present enough to receive the signal and recognize when there is interference. My best teachers have made me alert to this intentionality, a way of meaning it without the immediate necessity of knowing what I mean, which for me comes much later, when the draft is finished and I haven’t touched it for a while. Meaning it is fealty to the feeling, to making yourself available to embarrassment and the untidiness of discovery. Meaning it is joy, rage, spite. Meaning it is dangerous, because it is disharmonious with the costume many of us, for good reason, have developed to survive.

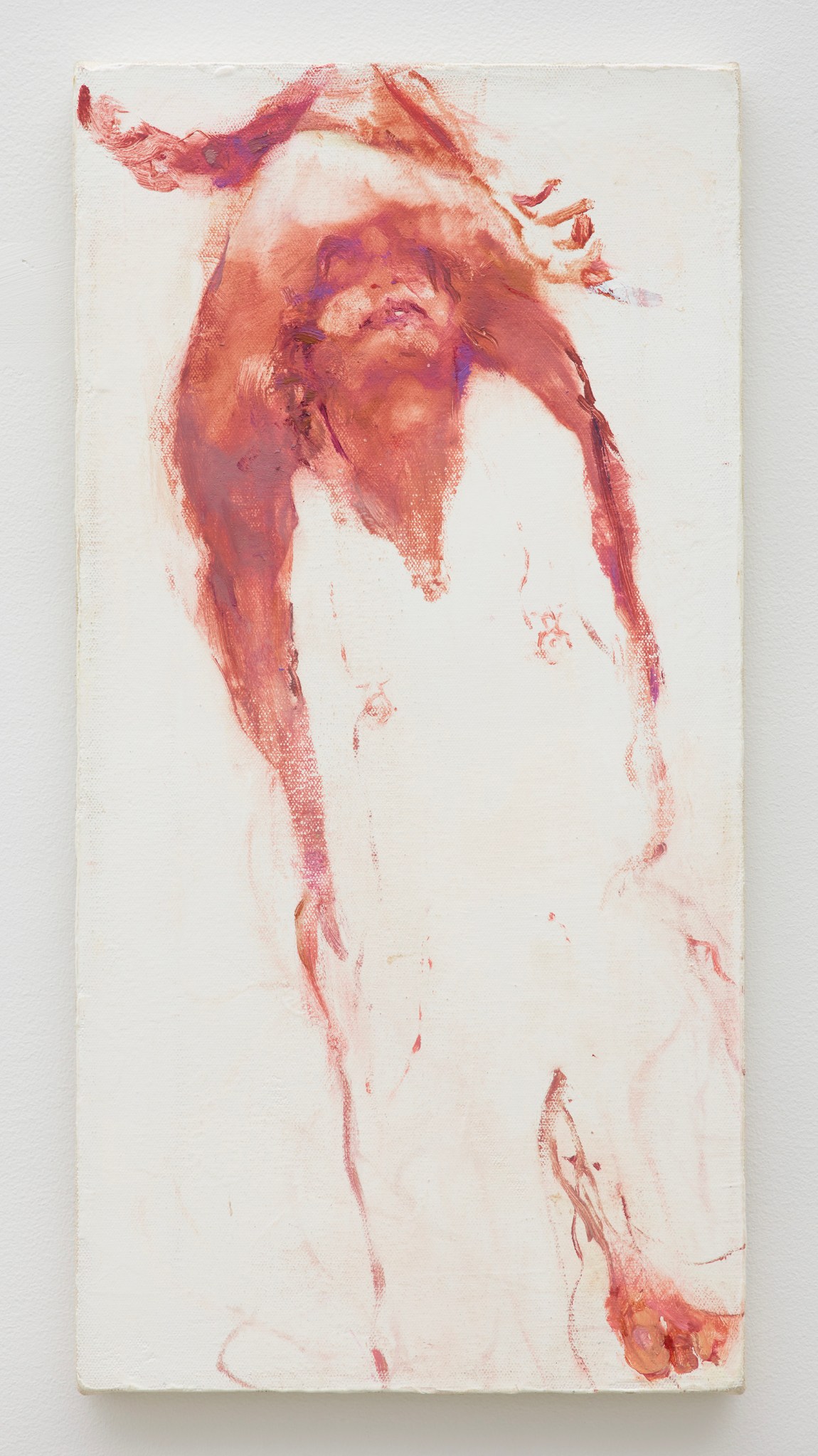

Meaning it is a matter of being clear without eschewing beauty or style or the honest nonsense that, as in good sex writing, reflects the primal misfires of the brain. I look for the feelings, where they’re concentrated and where they’re obfuscated. My writing process is above all about pleasure seeking. I read with a similar objective—to be overwhelmed by the specificity of an author’s private dogma, to feel their pleasure, to experience the hang-ups and perversions that inevitably, and sometimes accidentally, make it to the page. I read because I am a voyeur, because the novel traffics in the stealthy invasion of privacy better than our best machines. I return to Lorde’s directive to recenter the intuitive, and I seek out writers who demonstrate libidinal intelligence and a commitment to unhiding themselves.

*

The novelist Garth Greenwell has described writing as a willingness to inhabit bewilderment, and art as “the realm in which we can give full rein to the ambiguity, uncertainty, and doubt that we often feel we have to suppress in other kinds of expression.” His novel Cleanness (2020) is a careful taxonomy of doubt. In a chapter called “Gospodar” an unnamed narrator, a teacher and American expat in Bulgaria, details his submission to a dominant man he meets online. We experience the encounter in first person, as the narrator revels in and sometimes merely tolerates an escalating catalog of debasement. His private thoughts are untidy, unencumbered by a clear verdict. As he is compelled to strip, kneel, and suck, pleasure and fear coalesce with his feelings of silliness, uncertainty, extreme embodiment and also with the extreme disembodiment of processing his own personal history and the logistics of translating English to Bulgarian while he is, amazingly, engaged in the business of being on a leash.

Advertisement

Everything is happening at once, and the scene is effective in part because it urges its reader to hold that multiplicity. “No one is a type inside themselves,” Melissa Febos writes in one of my favorite essays about sex writing, in her book Body Work (2022),

and no performance is bereft of the actor’s own private consciousness. However deeply suppressed, the true story of our experience always plays out simultaneously. Unless the writer of these sexual experiences aspires to pornography, this truer story is usually the one more worth telling.

What makes pornography pornography, Febos suggests, is its emotional deadness and inherent phoniness—its flat appeal to archetype. It’s an author’s right to aspire to pornography. Greenwell himself has said that his goal was to write a scene that was “one hundred percent pornographic and one hundred percent high art.” But his fiction is all about the feelings, about their diversity and natural volatility, and we are meant to hold that reality even when, in “Gospodar,” a violation upends the erotic contract and the narrator has to fight to escape.

Over the course of the chapter, Greenwell explores the alchemy between epiphany and the state of in-betweenness from which we draw thought, art, and carnal paradox. “Sex is communication,” the novelist Alexander Chee has written, referring to another passage in Cleanness, and the minutiae of communication—its failures, its subtext, its permeability to one’s cultural and psychological leanings—are integrated organically into this sex scene, in part because the narrator of Cleanness is constantly negotiating the problems of translation. The narrator arrives at his new master’s apartment:

It would have made me laugh in English, I think, the word he used for himself and that he insisted I use for him—not that he had to insist, of course, I would call him whatever he wanted. It was the word for master or lord, but in his language it had a resonance it would have lacked in my own.

In just these first few sentences we feel the contradiction in the narrator’s emotional response to the regulations of their roleplay, his amusement with this bit of sexual theater right alongside the impulse to submit completely to it, the power differential between the two men and its divine implications, the presence of two languages—English and Bulgarian—that remove the narrator from his immediate situation to think about what is meant, the danger and eroticism of misinterpreting those meanings, and the hitch of “I think” that recurs throughout the novel and recreates the staggered quality of thought, affirming the collision of the cognitive and carnal but also the narrator’s doubt, which can make a sex scene feel alive.

The narrator doesn’t know how he feels about his own need, or whose need is the priority. Good sex writing embraces the moral difficulty of not knowing, of a person’s sexual trial and error and the array of bad or unsexy sex that might come from it. Brontez Purnell, author of the excellent 100 Boyfriends (2021), writes about that frankness as a necessity: “I use sex as a vehicle to lure people in and then trap them with the very human aspects of what the other side of sex is—it can be funny, unflattering, a bummer, a vehicle for friendship.”

In real time, the narrator is discerning the contours of his desire. After he is put on a leash he feels indifferent, awake to its pageantry. Greenwell allows him to experience moments of coolness and even boredom, and the scene is no less taut. Pleasure feels both more credible and integrated into the stakes, as fickle on the page as it is in life. Some things feel good, and other things are completely unerotic—an ambivalence that Susan Sontag, citing the Marquis de Sade, once argued cannot be found in pornography, where distinctions are obliterated and “revulsions are absurdities.”

Allowing for sexual complexity is especially important when writing marginalized characters. “Those of us fucking in the margins are often policed by our own communities to represent our sex in an idealized way,” Febos writes:

There are so few representations of our sex out there that we who find any kind of spotlight must speak well for the whole community. The idealization and marketing of our marginalized sex experiences as wholesome and perfect is a great argument against the argument for our depravity. But it also erases so much of our humanity. Queerness does not have to be healthy to be human.

Greenwell also resists the trap of respectability. He names desire earnestly, both by refusing to abbreviate it with irony and by giving his characters anatomy. They have bodily functions and genitals, and no curtain is dropped to obscure their splendor and grotesquerie. Sexual trauma and intercommunity violence exist alongside pleasure, and room is made for where they all join.

Advertisement

For Saidiya Hartman, writing honestly about the erotic lives of Black women is a necessary way to acknowledge our capacity for and right to pleasure, a rebuttal to the matrices of misogynoir that oversex and desex us and make us more violable. Part of her project is to render a Black girl who is sexually free—in her words, to “think about sensory experience and inhabiting the body in a way that is not exhausted by the condition of vulnerability and abuse…so definitive in the lives of Black femmes.”1

In Cleanness brutality is a neighbor to joy. As he is beginning to submit to his new master, the narrator says that “I found myself resorting again to habits I thought I had escaped, though that’s the wrong word for it, escaped, given the eagerness with which I returned to them.” Later he corrects with a different conviction:

I forced myself upon him with a violence greater than his own, wanting to please him, I suppose, but that isn’t true; I wanted to satisfy myself more than him, or rather to assuage that force or compulsion that drew me to him.

The halting cadences of thinking are felt in the repetition of words—maybe, almost, although, or—that leave the narrator room to revise. For example: “He took my hair in his hand and lifted me up onto my knees, not roughly, maybe just as a means of communication more efficient than speech.” Or: “He had said, don’t worry, and maybe it was just to ensure this understanding that he had taken me in hand.” Or: “He struck me five or six times in this way, or maybe seven or eight.” Later, as the encounter is going awry, those same words not only preface the internal digressions in which the narrator processes what’s happening and why or if he likes it, they also accelerate the action and telegraph that the narrator, hyperstudious, coiled deeply within his own consciousness, has become inarticulate flesh. He yearns to be released from the tyranny of his higher faculties, from the inclination of his mind to tunnel inward toward memory and analysis. He wants something: submission, pleasure, ego death. There are obstacles to getting those things but also new problems once he does.

*

“Gospodar” is a sex scene built around submission, ambiguity, the low hum of ceaseless self-interrogation that ambiguity creates, and an engagement with a knowing beyond your own faculties. For all intents and purposes it is an engagement with a kind of God, which comes with all of the normal pros and cons of zealotry and ferries you through languagelessness, humiliation, bodily transcendence, and the frayed boundary between pleasure and punishment. In Cleanness, languagelessness in particular is invoked to render the epiphanic and obliterative possibilities of sex. In this chapter, language is used to simulate processing, to establish and recalibrate power hierarchies between characters, to assert the concrete presence of the body, and to demonstrate how one’s linguistic faculties are blunted in the face of extremity. Greenwell’s syntactical choices are also, of course, in the service of beauty.

In her essay “Why We Get Off: Moving Towards a Black Feminist Politics of Pleasure” (2015), Joan Morgan writes about the limits placed on eroticism by cultural silences. She cites the scholar Evelynn M. Hammonds, who argued, in Morgan’s words, “that black feminism’s long-standing focus on the politics of respectability, cultural dissemblance and similar discourses of resistance…succeeded in identifying Black women’s sexuality as a site of intersecting oppressions” but in the process “inadvertently reified black female sexuality as pathologized, alternately invisible and hypervisible.” To resist those pathologies requires a “politics of articulation” and a rigorous attention to the mind. “Black female interiority,” Morgan writes, “is the codicil” to those silences.

Greenwell’s depiction of a person who is at once thinking and fucking liberates the sexual narrative from the flat exteriority common to standard pornography. Sex is just one way to establish character across time and isolate its unique ingredients. The encounter creates an opportunity to experience the narrator’s erotic continuum. He isn’t alone in a room with a man but with all his lovers, who come up worse or better in comparison. When Gospodar calls the narrator “she” it is both the humiliating sexual demotion he intends it to be and an invocation of the narrator’s homophobic father, who would not let him show any sign of femininity.

We understand when the narrator is instructed to strip before he enters Gospodar’s apartment, exposed to the locals of Sofia and the possibility of their bigotry, that his sense of peril is concrete. We understand the necessity of separating oneself from the relentless intrusion of the mind. Greenwell ushers us explicitly through the narrator’s reacquaintance with his lizard brain. He is described as a “difficult dog” and a “startled horse” edging closer to the languageless object he longs to be:

I leaned my head into him, resting it on his palm as he spoke again in that tone of tenderness or solicitude, Tell me, kuchko, tell me what you want. And I did tell him, at first slowly and with the usual words, reciting the script that both does and does not express my desires; and then I spoke more quickly and more searchingly, drawn forward by the tone of his voice, what seemed like tenderness although it was not tenderness, until I found myself suddenly in some recess or depth where I had never been. There were things I could say in his language, because I spoke it poorly, without self-consciousness or shame, as if there were something in me unreachable in my own language, something I could reach only with that blunter instrument by which I too was made a blunter instrument, and I found myself at last at the end of my strange litany saying again and again I want to be nothing, I want to be nothing.

This scene operates as a thesis for the section and delineates the narrator’s motivation, but it also captures a friction inherent to sex: the body’s brutal materiality and the sublime, boundaryless terrain beyond it. It echoes, again, that preliminary stage of artmaking that requires you to sit down with your real body to write sentences while rigorously engaging with your own oblivion. There is more precise psychological language for this phenomenon: regression in the service of the ego, which refers to the momentary, at least partially controlled use of primitive, nonlogical, and drive-dominated modes of thinking.

In a 2020 interview, Greenwell described both the libidinal drive and artmaking as border-crossing impulses:

The desire to exceed the body is always, or so it seems to me, a desire to destroy or unmake the self, to empty out the body…maybe with the hope—as for the mystics—that something else will fill us…. A desire for cleanness is necessarily a destructive desire, a desire for unmaking that would return us to some original state before contamination. Nothing in the world is more dangerous than that desire.

He writes sensitively about the human conditions that can make one long to be conditionless, about the wish for pure exteriority that returns us to the problem of interiority. The desire to be nothing, to be an object, has the filthy resonance of the pornographic vocabulary we know, but it is also a product of the soul. It’s one-hundred-percent pornographic and one-hundred-percent high art.