On a June night in 1997, two full moons appeared over the German town of Münster. One was smaller but no less bright, a frosted glass orb lofted over a patch of trees on a tall steel pole that its creator, the artist Isa Genzken, had erected on the shore of Lake Aasee. For parkgoers it was as if they had stepped into the era of Romanticism, with its haunted lunar fixation, only the vision was doubled. It was a familiar gesture for an artist who tends to cultivate “a zone of uncertainty” around her sculpture, as Birgit Pelzer, one of her earliest critics, commented in 1979. Here, in Westphalia, the zone was deliberately soused, Hölderlin after a few pints. Drunkenness and madness have long been associated with the moon, Genzken wrote in a text published when the sculpture, Vollmond, debuted. Confronted with a woozy moon so close to earth, some parkgoers might have asked themselves, “Have I gone crazy?”—a fitting question considering that Genzken once declared herself “the only female fool.” Vollmond was at once a witty précis of her career and a daring self-portrait.

This summer a large survey of Genzken’s sculpture, “75/75,” opened at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, organized by the museum’s director, Klaus Biesenbach, with the curator Lisa Botti. It was occasioned by the artist’s seventy-fifth birthday and features seventy-five sculptures spanning her entire career, from her ingeniously designed Ellipsoids and Hyperbolos of the 1970s and early 1980s—attenuated, javelin-like works—to her later assemblages of textiles, mannequins, and found images and objects.

The towering, stainless steel Pink Rose (2016/2023) blooms over the museum courtyard. Destined for selfies, it is a crowd-pleasing opener to Genzken’s first ever large-scale institutional show in the city she has called home for decades. Pink Rose is part of her well-known series of hyperreal flowers—mostly roses, though she has created orchids, too, and in 1988 planned (but never realized) an arch of tulips for a highway outside Amsterdam—that introduce a note of provocative whimsy into their urban settings. Made from stainless steel, aluminum, and lacquer and reaching as high as thirty-six feet, they draw attention (and now your phone) to our smallness and prettify the inorganic material from which cities are built.

These monumental flowers consent a little too easily to the expectation that public art be idiot-proof, but they also hint at a discerning economic critique. The ludicrous tulip craze of the 1630s was a precursor to many financial bubbles to come, and Genzken’s reference would not have been lost on Dutch commuters in 1988, only a year after the Single European Act, which ensured the creation of a single market for European member states, went into effect. Her roses—among other things, symbols of doomed twentieth-century socialism—have been especially effective in New York, where they were installed on the façade of the New Museum (itself built two doors down from a homeless shelter), in Zuccotti Park on the tenth anniversary of the 2008 financial crash, and in the sculpture garden at the Museum of Modern Art—all sites where capital is exalted, where treasure and influence have accumulated, and where the social contract has eroded. Yet the sculptures’ popularity also suggests a politics at least partly disarmed by their beauty; museum board members and their critics adore the monumental flowers. We buy a rose for our beloved and we lay a rose for the dead.

Pink Rose is the only public work included in “75/75,” which is otherwise confined to the ground floor of the museum. Only seventy-five visitors are admitted at a time, ensuring that the show stays intimate. It is a welcome strategy for an artist whose more recent sculptures require time and space to walk around but depend on the smallest material detail: salvaged fabrics, bits of toys, newsweeklies, umbrellas, car parts, and a flight of snapshots of Manhattan fixed to a tower of patchy holographic and mirrored foil. Some of the sculptures are stationed close to the glass walls of the gallery so that skateboarders, who dominate the wide surrounding courtyard, can glimpse the exhibition from outside.

The skaters’ constant scurrying at the margins, especially near Genzken’s later, sportier pieces, which feature mannequins draped with bright articles of clothing, is a cute distraction the artist might appreciate; she once said her art was “rather cinematic” and should be viewed as “moving images.” Movement is both integral to the work, as in the spinning recliners of Zwei Regiesessel (2003), and incidental, almost atmospheric: a glossy poster of Michael Jackson dancing on the balls of his feet is fastened to the columnar Wind (B) (2009) and wavers gently when you pass by. Superficially, her work deals in the cinematic with the use of publicity shots of celebrities, especially beautiful men like Jackson and Leonardo DiCaprio. (“75/75” skirts a great deal of Genzken’s practice, from painting to photography to video. As a result, some crucial works are absent: DiCaprio is sorely missed.) But these infatuations are more haunted than fannish: she reveres male beauty while seeming to imply that there is something terminal and risky and maybe even oppressive about it. DiCaprio’s handsome young face is prominent in her picture-laden slot machine, Spielautomat, from 1999—one of her most famous sculptures—and in a 2000 art book about him, Mach dich hübsch! (Make yourself pretty!).

Advertisement

Some of Genzken’s critics have been hostile to her changing artistic identity and her “frantic, angry urban vision fuelled by nihilistic inertia,” as Ariella Budick put it for the Financial Times in 2013, on the occasion of a retrospective at MoMA. The Nationalgalerie’s tight selection, installed on a grid that leads visitors chronologically around the open floor plan, makes the development of her recurring motifs clear for the baffled or uninitiated: we see her spirited, playful use of materials, from concrete to plastic, as well as her open approach to how junk might be dressed up or down into novel aesthetic forms.

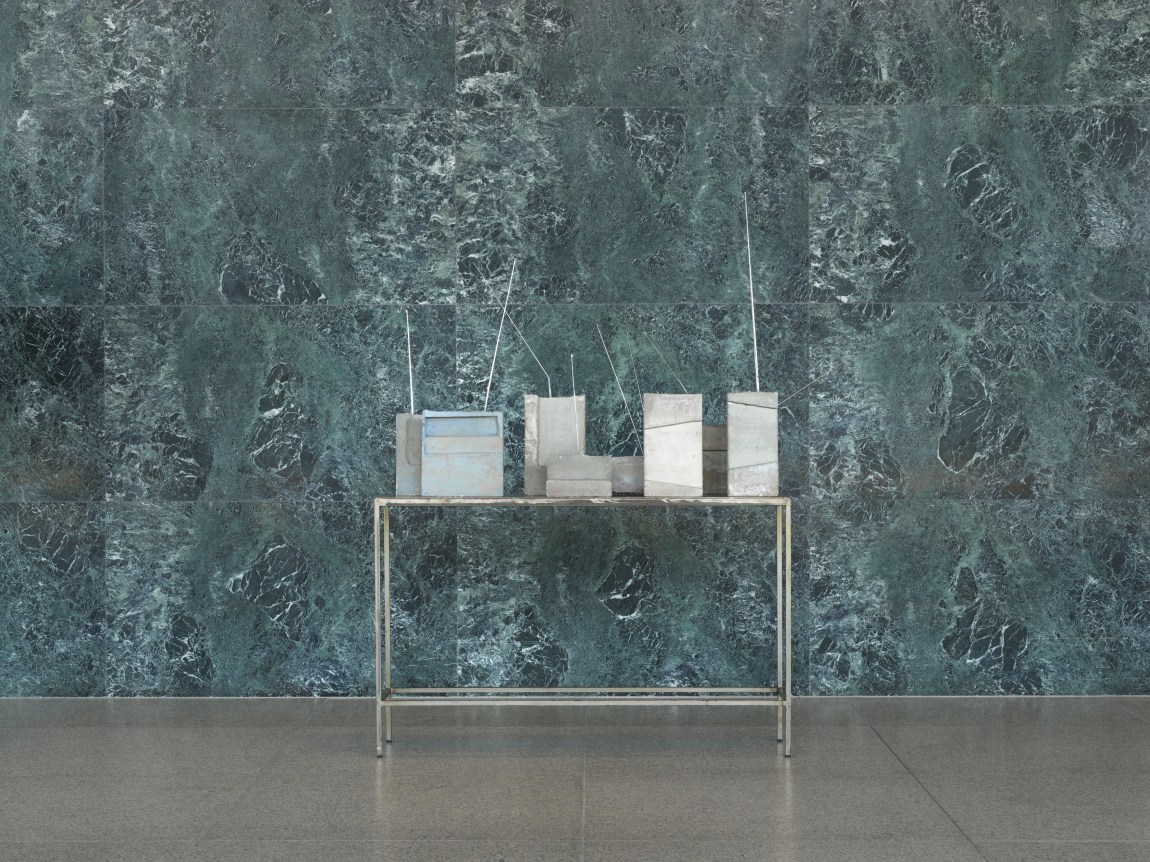

Among the early works are the Weltempfänger (World Receiver) series—squat chunks of concrete with radio antennae sticking up from their tops—and the Fenster (Window) series of the early to mid-1990s. The Weltempfänger were first shown in 1987 in the windows of MUSIX, an electronics store in Düsseldorf. As the art historian Lisa Lee writes in Isa Genzken: Sculpture as World Receiver (2017), the first English-language monograph on Genzken, the series announced her “receptivity—to art history, to social, political, and economic currents—as a defining characteristic of her oeuvre. Intractable substance, the stuff of sculpture, reverberates with and is made responsive to life itself.” That the world receivers appeared in a West German shop window rather than a gallery emphasized how embedded her practice was in the fabric of daily life. The radio was central to cold war politics in the two Germanys. Genzken came of age in a period of ideological combat on the airwaves, and she was fascinated by the midcentury electronics revolution, from transistor radios to the cutting-edge computers that helped her create the precision-engineered Ellipsoids and Hyperbolos that open “75/75.”

*

Many of Genzken’s contemporaries were concerned with national guilt and the horrors of history buried under the thin topsoil of the present. Her vision was less solemn but no less political, even if those politics have been hidden in plain sight. In a photograph of the 1987 show, the World Receivers blend into the MUSIX window display alongside actual radios that were for sale, suggesting an art within reach, even if their lack of functionality meant that anyone hoping to tune into WDR would be wasting their deutsche marks. More generally, the series showed her fascination with how common goods might be made weird. “There is nothing worse in art than ‘You see it and you know it,’” Genzken once told the photographer Wolfgang Tillmans, a longtime friend and collaborator. “After all, art is often on the edge in the sense that in one moment it seems really very close, and the next moment you find it doesn’t.”

Born in Bad Oldesloe in 1948, Genzken studied art in Hamburg and Berlin before transferring to the prestigious Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 1973, where she was taught by Joseph Beuys. A decade later she married the painter Gerhard Richter. (The period after their divorce in 1993 was one of immense personal struggle for her—she blew money drinking with gay hustlers at Blue Boy in Berlin and was eventually hospitalized after a breakdown.) Toward the end of her marriage she produced two series of abstract paintings, “Basic Research” and “More Light Research”: ghostly, photogram-like depictions of geographic topographies, suggestive of eerie surveillance imagery, and gymnasts’ rings.

She continued experimenting with minimalist forms in her sculpture, but her work in other media grew more expansive and less austere. In the mid-1990s she produced three artist’s books later collected as I Love New York, Crazy City, an exultant homage that collages her own photographs with found images. Two films from 1992 take the measure of daily life in the US and Europe: in Chicago Drive, she shot the city for the Renaissance Society, touring a cemetery and local architecture, and in Meine Grosseltern im Bayrischen Wald, she showed the quiet lives of her grandparents in the Bavarian forest shortly before their deaths. That decade she also installed a number of public sculptures. Camera (1990), a giant tilted steel frame atop a building in Brussels, looks like it might fall on your head, which Genzken acknowledged was partly the point. She strung a nylon cable between three buildings in Toronto (Two Lines, 1991) and designed a nonfunctioning wind turbine for Hanover (Proposal for Art and Wind Energy, 1998). Her first Rose appeared in Baden-Baden in 1993.

Advertisement

Around 2000 she mostly moved away from minimalist sculpture, and her work became playful. She explained to Tillmans that the change was sudden: “Just go ahead.” Her sculpture seemed as rigorous as ever but increasingly makeshift and tentative, trading more robust building materials, like concrete, for cheap plastics. Many of these works can seem to be little more than rubbish ready-mades: detritus constructed into towers and maquettes and layered onto mannequins. But in her winking subversion of everyday objects, she continues to play a dire Dadaist game in which the familiar is not only defamiliarized but pushed toward collapse.

The critic Hal Foster has pointed to Genzken’s affinity with Dada, which aestheticized the crises of the 1920s as subjective experiences: “She, too, practices a mimetic exacerbation of the emergency conditions around her.” This is especially obvious in the work inspired by her stints living in New York in the 1990s and early 2000s, in particular by her experience of the September 11 attacks (she happened to be visiting when the towers fell). In a collection of sculptures that amounted to an informal proposal for how to rebuild Ground Zero, she offered a stunning, if impractical, vision for the World Trade Center site, a run-down riposte to Daniel Libeskind’s slick master plan of 2002: seven skyscrapers improvised out of colored plastics, metal carts, artificial flowers, and more. It was a delightfully Party City proposal in its choice of materials for a site meant to memorialize and somehow overcome national grief. Only one, Hospital (Ground Zero), appears at Neue Nationalgalerie, though the inclusion of Empire/Vampire III, 12 (2004)—a miniature war scene of toy soldiers mired in a pile of sunflower seeds, created a year after the invasion of Iraq, that portends the disastrous course of the war—nods to her more critical engagement with the politics of the Bush era.

*

The last third of “75/75,” featuring sculptures made during the past two decades, projects the glitzy materiality of nightclubs and gay bars, graffiti, pop culture, and contemporary fashion, with gestures to recent art history and architecture—Fuck the Bauhaus (2000), New Buildings for Berlin (2001–2014), and Mies (2008)—as well as antiquity (Nefertiti busts are a common feature in her work) and the Renaissance (two sculptures here from 2017, both titled Leonardo). The Actor series in particular, fashion mannequins in various rigid poses, can seem thrown together, but the formal power of her work in this period relies on a balance between the effluvia of metropolitan life—some of it direct from the artist’s closest—and subtle nods to classical sculpture and architecture. One female mannequin is dressed in jeans and a white bonnet, with one breast spray-painted blue. It leans on its side, a mirror propped against a nearby wall reflecting the torque in its crossed legs, striking a pose that has defined representations of women from the Sleeping Ariadne in the Vatican Museums to Barneys today.

The work is also funny. Another mannequin, of a little girl, is draped in a shower curtain and red satiny coat. Its face is covered by a Jason Voorhees mask, with two scalp massagers stuck like antennae into an overturned fruit bowl (is it Alessi?) that sits on its head. Untitled (2012), a gruesome Halloween mask impaled on the leg of an upturned plastic chair and glamorized by a pink-and-blonde wig and silvery paper visor, is a sight gag that suffers from description. Throughout the last third of the exhibition, art made when she was “just going ahead,” you can practically hear Genzken’s laughter at “the vulgarity of the revered,” to borrow a line from an Edmund Wilson essay on Charles Dickens. “It represents, like the laughter of Aristophanes, a real escape from institutions.”

Genzken retired shortly before the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. Many critics have clumsily tried to connect the sculpture of her later years to her personal life, especially to her alcoholism and bipolar disorder. Even Benjamin Buchloh, one of her most generous and thoughtful champions, argued in Artforum that the disintegrated physical state of the art reflected the disintegrated mental state of the artist:

To have the self succumb to the totalitarian order of objects brings the sculptor to the brink of psychosis, and Genzken’s new work [from 2004] seems to inhabit that position. However, since total submission to the terror of consumption is indeed the governing stratum of collective object-relations, that psychotic state may well become the only position and practice the sculptor of the future can articulate.

When The New York Times profiled her in 2013, after she had initially rejected an interview, the journalist was consumed by questions about her sanity. This would be totally unthinkable for a male artist on the eve of a major MoMA show.

Genzken herself has only ever been indirectly autobiographical in her sculpture. Photographs of her appear occasionally, affixed to the sculptures, as does her name—more than just a signature. (She spraypainted “Isa” on a car hood for Untitled (2018), which hangs from the ceiling in “75/75.”) Her face appears three times in the work on display at Neue Nationalgalerie. In a picture clipped to the head of a child mannequin in an Actor from 2012, she sits on a windowsill in midtown Manhattan, Central Park visible behind her. She appears twice in Untitled (2015), four towers and three columns adorned with mirrored foil, plastic flowers, a cigarette, newspapers, magazines, and various other materials. Inside one tower a recent picture shows her face contorted in agony.

On the other side of the sculpture is an earlier photograph of her and Richter. They don’t look like they’ve slept much, nor do they seem especially happy. They were an uneasily matched pair—a subdued painter who loved the countryside, an exuberant sculptor who loved the city. For Genzken history has seemed less burdensome, while the German past has weighed heavily on Richter, who is sixteen years her senior and whose memories of the war were firsthand. Genzken’s influence on contemporary art has been somewhat quieter; she is considered an “artist’s artist,” while Richter is a giant of postwar art. But today, you need only ask young artists to name their top three: Genzken often makes the list, while Richter is for the dads.

The final sculpture on the show’s grid is a deceptively ad hoc, spray-painted pile of newspapers and magazines, plastic bags, and a DVD with Genzken’s name printed on it. This is the subtlest of her late works, a literal collapse. Dreary headlines are heaped into an image of our present “emergency condition” that is both urgent (“Zero Hour,” a Der Spiegel headline) and depressing (a giant emoticon on a copy of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung frowns under the line “Have a laugh,” not far from an issue of Berliner Zeitung that declares “This Is Why We Need Sexism”). The piece reads like a Dadaist self-portrait, a way of executing Tristan Tzara’s “To Make a Dadaist Poem” from 1920, in which he encourages writers to cut out each word from a newspaper article, shake them in a bag, then make a new text by drawing out one word at a time. “The poem will resemble you,” he declares. “And there you are—an infinitely original author of charming sensibility, even though unappreciated by the vulgar herd.”