“Slut” and “whore” evince, like piped exhaust, the running engine of Mean Girls. Early in the original film, our protagonist and narrator and new girl, Cady Heron, is recruited by two classmates, Janis and Damian, into a revenge plot against “the Plastics,” a trio of popular girls perched, in four-inch pumps, at the tippy-top of the pecking order at North Shore High. Janis introduces Regina, the head hen, to Cady, and to us in turn, as follows: “Don’t be fooled, because she may seem like your typical selfish, back-stabbing, slut-faced ho-bag. But in reality, she is so much more than that.” And we’re off.

Permit me to recount a scene that is by now well known. Cady strikes out on her own one night, going solo in an act of “major plastic sabotage,” previously a three-person job. It goes down in split-screen. Over a seeming two-way phone call, Cady asks Regina if she’s mad at Gretchen, her second-in-command, for having been nominated for Spring Fling Queen, a title Regina has held since time immemorial (that is, two years of high school). “I’m not mad at her,” Regina tells Cady while eating a donut, “I’m worried about her,” namely about what will happen when nobody votes for her—though Regina swallows the “when” along with her pastry, leaving open the generous, though implausible, interpretation that the warning is instead conditional, an implied “if.”

“So you don’t think anyone will vote for her?” Cady asks, a request for clarification that doubles, as we’ll understand in hindsight, as an incitement—a knife-twist into an eavesdropping body offscreen. But what’s crazy, Regina goes on, taking another bite, is that the nominee “should be Karen, but people forget about her ’cause she’s such a slut.” On that note, she exits, off to bed—or so she tells Cady just before the partition between them slides leftward, pushing her offscreen. A new partition, a new girl, enters from the right: Gretchen, who’s been on the call all along.

Gretchen starts dialing. While she passes from room to room, the screen’s composition alters again: Karen enters in a frame of her own, and now Gretchen is the fulcrum in this game, a round of telephone in which the message is that your best friend thinks you’re a slut. But Regina won’t be left out. She wants to go out, hitting Karen’s line to that effect, reentering the fray as a fourth quadrant, though still deprived of the full picture. The game continues apace, an escalating round-robin of two-way exchanges: Regina and Karen to Karen and Gretchen (and Cady) to Karen and Gretchen (and Cady—again, as Karen flubs the switchover) to Karen and Regina to Karen and Gretchen (and Cady) to Gretchen and Cady to Karen and Regina. Regina, Regina, Regina, alpha and omega of a game she’s not even playing tonight. The scene’s most memorable line is her sign-off to Karen: Boo, you whore!

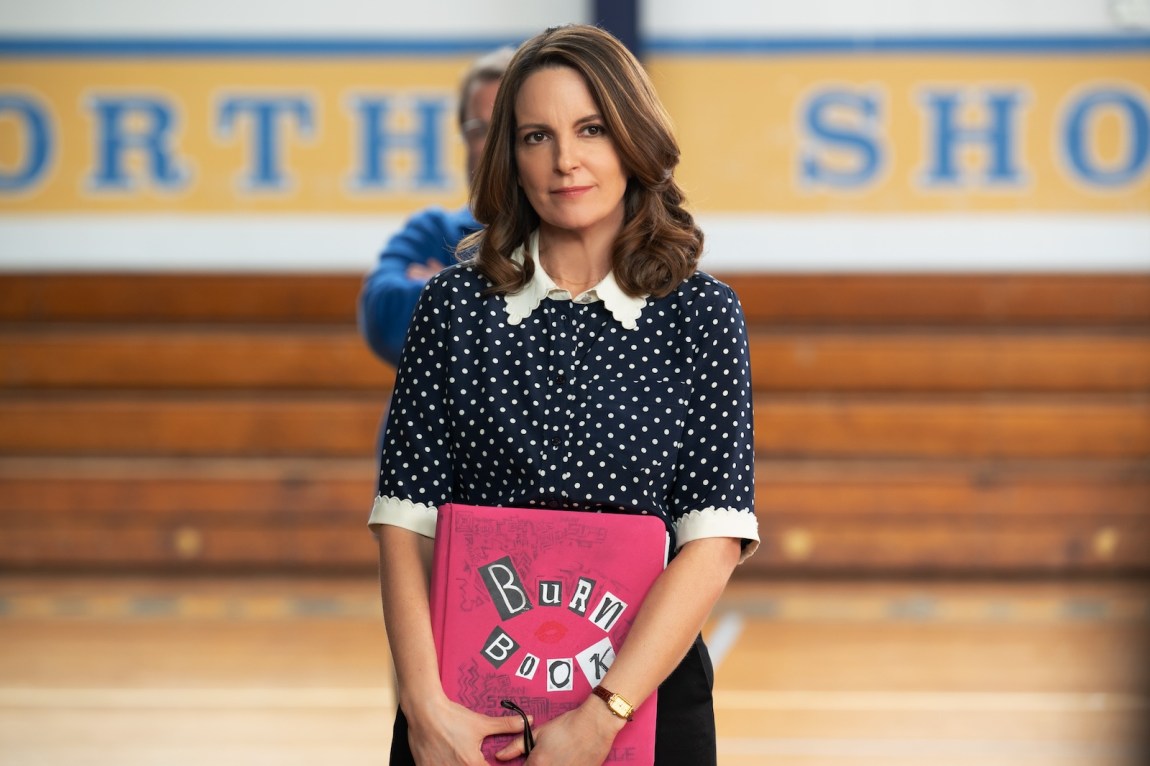

Apart from their local color, these “sluts” and “whores” have a message. At the film’s climax, photocopies of the Plastics’ private backbiting “Burn Book” are strewn throughout the school hallways. Cutting across the cliques that were introduced at the start of the movie, the conspiratorial putdowns gathered therein serve the purpose of all good gossip, “perhaps the most familiar and elementary form of disguised popular aggression,” as the political scientist James C. Scott has written. “Gossip,” he continues, “reinforces…normative standards by invoking them and by teaching anyone who gossips precisely what kinds of conduct are likely to be mocked or despised.” Kaitlyn Caussin is a fat whore. Dawn Schweitzer is a fat virgin. Trang Pak made out with Coach Carr. Amber D’Alessio made out with a hot dog. Janis Ian: dyke. Damian: too gay to function. Regina George is a fugly slut. Enough said, the junior girls resort to beating the shit out of one another. Ms. Norbury, played by the architect behind the film’s joke-making, Tina Fey, intervenes: “You all have got to stop calling each other sluts and whores. It just makes it okay for guys to call you sluts and whores.”

*

This is the point at which viewers might recall that it is 2004, in the thicket of Bush-era angst over the bilious homosociality demanded of a teenage girl, that bottomless well of sympathy and scorn. In the Nineties researchers in child development formalized the notion that girls could be as aggressive as boys, exploiting their social gifts with what Nicki R. Crick and Jennifer K. Grotpeter, in a 1995 study, called “relational aggression.” In contrast to boys’ “overt aggression,” Crick and Grotpeter found that girls were “significantly” more prone to express their hostilities “relationally,” that is, in

Advertisement

behaviors that are intended to significantly damage another child’s friendships or feelings of inclusion by the peer group (e.g. angrily retaliating against a child by excluding her from one’s play group; purposefully withdrawing friendship or acceptance in order to hurt or control the child; spreading rumors about the child so that peers will reject her).

The authors surmised that the “paucity” of research on girlside aggression could be due to its subterranean complexity. A punch is easier to trace back than a rumor. The uninitiated and uninformed will miss much.

By the early 2000s, concern over relational aggression as such had trickled into the Borders parenting shelves. Two nonfiction bestsellers on girlhood aggression appeared in 2002: Queen Bees and Wannabes: Helping Your Daughter Survive Cliques, Gossip, Boyfriends, and the New Realities of Girl World by Rosalind Wiseman and Odd Girl Out: The Hidden Culture of Aggression in Girls by Rachel Simmons. Wiseman was the subject of a New York Times Magazine profile in the runup to her book’s publication, fast-tracking her treatise on “Girl World” to the eyes of Tina Fey.

In her recent book So Fetch: The Making of Mean Girls (and Why We’re Still So Obsessed with It), Jennifer Keishin Armstrong reconstitutes the milieu that made Mean Girls a thing, both before and after the movie premiered. Teenaged cliques were by no means a new phenomenon, but popular thinking about them was changing. Those anywhere near the target market got that thinking served up to them in fiction series such as Gossip Girl (2002–2011), The A-List (2003–2010), and The Clique (2004–2011), titles telegraphing as subtly as a feature called Mean Girls.

Although the girlboss as we would come to know her had not yet received her book deal, the climate was being readied for her arrival. Relational aggression and its stratagems—including, say, playing dumb to attract attention—is as bad as it sounds, the literature relayed, but can we not, for a moment, hand it to these beautiful girls who’ve spun their limited autonomy into autocracy? “On the one hand, it is kind of satisfying to think that girls might be, after their own fashion, as aggressive as boys,” Margaret Talbot wrote in the Times Magazine article, headlined “Girls Just Want to Be Mean.” “It’s an idea that offers some relief from the specter of the meek and mopey, ‘silenced’ and self-loathing girl the popular psychology of girlhood has given us in recent years.”

Fictional and nonfictional appreciations of the girl seized upon a familiar feminine symbol, a color: pink. And not your mother’s or older sister’s pink—not the homespun femininity of Molly Ringwald—but the ditz theater of The Simple Life. It was pink like Paris, posed against a shimmering pink bedspread in a pink dress on the cover of Confessions of an Heiress: A Tongue-in-Chic Peek Behind the Pose (cowritten with Merle Ginsberg), published months after Mean Girls premiered, the year after someone leaked the twenty-two-year-old’s sex tape. “It’s all about taking charge and branding yourself,” Hilton told Reuters during her publicity tour for the book. “I think we’re living in a moment when having a career, especially a really glamorous one, is very sexy.”

Wiseman grew fluent in the ways of middle school girls, Talbot reports, by running workshops to help them be nicer to one another and collapse their local fiefdoms. Perhaps taking a cue from the primitivist idioms common to so much social science—Crick and Grotpeter cited the importance of observations conducted in “naturalistic settings”—her book reaches for taxonomy, identifying the patterns of “Wannabes” and “Alpha Girls” and “Gamma Girls.” In the profile she unveils Girl World’s stratagems, such as three-way calling: “O.K., so Alison and Kathy call up Mary, but only Kathy talks and Alison is just lurking there quietly so Mary doesn’t know she’s on the line. And Kathy says to Mary…” Wiseman also introduces Talbot to a teen named Jessica, “an amalgam of old-style Queen Bee-ism and new-style girl’s empowerment, brimming over with righteous self-esteem and cheerful cattiness,” who freely recites her clique’s lunch table policy:

O.K. … No 1: clothes. You cannot wear jeans any day but Friday, and you cannot wear a ponytail or sneakers more than once a week. Monday is fancy day—like black pants or maybe you bust out with a skirt. You want to remind people how cute you are in case they forgot over the weekend.

But Talbot, who recalls that her tween self was “neither a picked-on girl nor an Alpha Girl, just someone in the vast more-or-less dorky middle,” wonders if so much attention isn’t in fact reinscribing the categories experts like Wiseman purport to quash. Close study, after all, requires some degree of magnification.

Advertisement

Meanness not quashed but nurtured, rehabilitated. Fey was a mean girl herself, as she’s told it, her adolescent judgments—which did not confer popularity—braided with a killer wit. But shortly after her promotion to head writer at Saturday Night Live, she surmised that it took more than wit to be popular. In So Fetch, Armstrong reminds us that the transforming figure of the mean girl ran concurrently with the reinvention of Tina Fey, live from New York. She shed her Midwest fluff, went shopping at French Connection, and wore the frames that would win her appellations like “specs symbol” and an entry in Urban Dictionary (“Tina Fey Glasses”). The makeover “would later be mythologized as a calculated, and successful, attempt to make the jump from writer to on-screen talent,” writes Armstrong. It was pink in spirit, a self-styled blushy feminism. Armstrong admits, with chagrin, that she was caught up in this turn, cofounding a website called Sexy Feminist and later coauthoring the book Sexy Feminism. “Pink, as you can imagine, was very much embraced and celebrated,” she writes.

Mean Girls both leveraged this fixation and catapulted it to new heights. It also brought Fey to Hollywood. She read Talbot’s piece on Wiseman and conceived of a comedy about Girl World, initially something dark. “When I first started working, I watched a whole bunch of teen movies, mostly to make sure I didn’t bump into them too hard and inadvertently rip them off by not remembering what was in them,” Fey said in a 2004 interview. “And when I first watched Heathers, I was, like, ‘Oh, right. Somebody made this movie already.’” She course-corrected her pitch to “a more hopeful Heathers,” ultimately truer to the source material of Wiseman’s book. Lorne Michaels—head hen at SNL and, for the show’s talent, gatekeeper to funding for extracurricular projects—gave it the go-ahead on one preliminary condition: “Okay, but can they also still have cool cars and cool clothes?” Check and check.

*

It’s a parable of socialization. A naïve girl from—but not of—Africa returns to the US equipped with mere jungle sense, having been homeschooled by her American zoologist parents, and must acclimate to the unfamiliar wilds of high school in Evanston, Illinois. She falls prey first to Janis and Damian, then to Regina, and then, quite liking her ascension to Queen Bee status, to her own id. (Her name, spelled C-A-D-Y and said like “Katie,” is several times read aloud as “catty.”) Everything blows up in her face, of course, but the consolation prize is a lesson about playing demonic mind-tricks and speaking ill of other girls. Girl World repairs into something humane, though the next generation haunts the periphery.

Heathers purges its monarch, killing her off in the movie’s first third. A handful of queeny one-liners, one bad party, and it’s off with her head. But Regina is everything. “Regina George’s image towered over the production of Mean Girls like a giant, supercilious Barbie doll, glaring down at her kingdom and casting judgmental looks over all who were working to make her Girl World come to life,” Armstrong reports. “Cady may have been the main character, but the aesthetic was dictated entirely by Regina. She demanded to be honored with the right sets, clothing, hair, makeup, lines, and scenes.”

Lindsay Lohan wanted to play her. She had already played the offbeat heroine in Freaky Friday and Confessions of a Teenage Drama Queen: “I was still seventeen years old and I wanted to be cool girl on set.” (She would still be the cool girl on set.) But Rachel McAdams, older with theater training, had a daunting effect on her reads with Lohan that locked their roles into place: Lohan would play the ingenue, the wide-eyed Cady to McAdams’s Regina. McAdams would still need a nudge to go full bitch—the film’s director, Mark Waters, had her rehearse her lines with an original version of the script, laden with “fucks” that were removed in the interest of a PG-13 rating.

So Fetch is a book about the persistence of Mean Girls, a film as of its time as anything else, but which—unlike contemporaries with comparable palettes (Legally Blonde, 13 Going on 30) that survive primarily as nostalgic set pieces—has a vibrant afterlife in idiom. Out of Armstrong’s extensive research come a number of ways to understand its staying power, from the launch of a certain proto-girlboss ideology to Lohan’s burgeoning star appeal to the financial needs of Paramount Pictures to BuzzFeed editorial workarounds to sheer good luck. The book unfortunately lands upon its least convincing explanation: that Mean Girls persists because of the universality of its message, a matter of “generations feeling connected to the story, seeing themselves in it, and making it their own.” Every generation is owed its Mean Girls.

But wouldn’t it make better historical sense, by that reasoning, to say that each generation gets its own Heathers? (Not only did Fey take copious inspiration from Heathers, Waters, who directed Lohan in Freaky Friday prior to Mean Girls, is the younger brother of Daniel Waters, who wrote the earlier film’s screenplay.) Let’s be honest: the message of Mean Girls yields to the comedy, effected by jokes as executed off the page. As Richard Brody wrote on the ten-year anniversary of the film’s release, in an essay quoted by Armstrong, Mean Girls quotables are inextricable from “the inflections and the distinctive voices of the superb actors who deliver them…and give them an imposing, three-dimensional authority, like mobile language-sculptures.” Comedy is the thing; it always has been for Fey.

*

Armstrong is interested in why we keep returning to Mean Girls, why we keep bringing it back, and I’m as yet undecided on whether these are distinct questions. After Fey learned that college students were performing their own adaptations of the film onstage and heard rumors that professional dramatists were interested in doing the same, she made her own pitch that, with approval and backing again from Michaels, became Mean Girls the musical, with music by her husband, Jeff Richmond, and lyrics by Nell Benjamin (who, with Laurence O’Keefe, was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Original Score for the 2007 musical adaptation of Legally Blonde). Fey, naturally, wrote the book. Wiseman, despite corresponding with Fey, seems to have never invited into the fold in a real way. Hoping to use her antibullying advocacy to reanimate the message behind the memes, she designed an educational program with the production’s blessing and consulted on the script, but with the approach of opening night she was, she has said, ghosted. Later, she detailed in a 2021 blog post, “one of the producers admitted that his role was to work with me so ‘I wouldn’t upset the apple cart.’”

Mean Girls opened on Broadway in 2018, and though the pandemic forced it to close after twelve Tony nominations and 833 performances, it has been touring ever since and is scheduled to open in the West End this summer. The consensus among reviewers—plus a close friend—seems to be that the production ably adapts its cinematic source material, adding in the social Internet and excising the “r”-word (and another, statutory rape). I haven’t yet had the pleasure, and so my first experience of a musical Mean Girls arrived with the film Mean Girls (2024), adapted from the stage adaptation of the film Mean Girls (2004).

A clique is only as plausible as its faith in cool. “You just need to find your clique and commit to it,” new Damian tells Cady early in the movie as they survey the cafeteria, and it was around here that I had the feeling this Mean Girls wasn’t going to work. Cady’s options are “jocks,” “corny horny band freaks,” “burnouts,” “grade grubbers,” “theater mess.” And the Plastics, of course—not an option so much as a summons, membership pending Regina’s noblesse oblige.

But what here distinguishes the Plastics, really? Are they richer, better coifed, better dressed than their cast-offs? Not really. Everyone in this version of a high school ecosystem is a little cool, in command of the sort of curatorial style enabled by the fast, infinite fashions on SHEIN.com or any other online retailer. Mall culture has gone and so, apparently, have acne, segregation, and frizz. During preproduction of the original movie, Lizzy Caplan gave herself an antimakeover before the table read for her role as the art loser Janis Ian, from “uncommonly beautiful,” as the casting director Marci Liroff put it, to goth—two descriptors placed in opposition by the film’s aesthetic regime. Her onscreen successor, Auli‘i Cravalho, is a magnetic presence as Janis ‘Imi’ike. With her septum piercing, wide-legged jeans, makeup evocative of Maddy Perez (the about-it Queen Bee on Euphoria), and fluency in a social justice idiom, forgive me for supposing she was the cool one. The role has grown—in the absence of Cady’s narration, Janis and Damian (Jaquel Spivey) move us along as troubadours. Their chemistry is alive but the terms of their ostracism unclear. Have they banded together as outcasts, or as a found community? What do I, a junior millennial, know—but if borders are being drawn, a map would do nicely.

Then there is the awkward business that has become the specter of Africa in this story. In the new film it is not abolished so much as smudged, with 2010s liberal politics plastered on top. In the original, race humor amalgamates the cheap laugh of a white girl from the dark continent with equally cheap laughs at the expense of American blackness. (Learning of a new student “from Africa,” Ms. Norbury greets the nearest black student who is, as the student snaps back, “from Michigan.” In a nearby scene, Cady greets a table of black students in Swahili and they glare back.) In 2024 the jungle motif remains, vivid as ever, yet skitters from its antecedent. Cady (Angourie Rice) is from a country now, Kenya, but her first crush isn’t Nfume, a small black child shown against the backdrop of the Savannah, but “this Peace Corps guy.” The Kälteen bars, dangled to Regina under the cloak of diet food, aren’t intended for underweight “kids in Africa” but for unspecified “elderly people.” Cady’s quirky fandom has been redirected from the South African choir Ladysmith Black Mambazo to Neil deGrasse Tyson. The plot needs Africa, yet runs from its own appetites. Cady otherwise might as well have been from Estonia, or Alberta.

Gender also takes an oddly congenial form. Bet that in 2024 we do not call each other sluts and whores except as affirmation of an individualized bodily autonomy: “Cady, if you don’t dress slutty, that is slut-shaming us,” Gretchen says (is that wink?). As a twofold trace of the old, Regina does mock Karen for letting her bra show as “a look”: “Is it ‘girl who slept with eleven people’? ’Cause you’re nailing it.” But otherwise, normative standards, to be observed by their enforcement, are hard to locate. Perhaps all that normalizing worked. Perhaps everyone is nicer, no longer working so blue. Regina, to Janis, is now a “scum-sucking life ruiner” and Janis, in turn, a “pyro-lez,” but the “pyro” exacts more reputational damage, it seems, than the “lez.” “Fire-crotch,” a pejorative incidentally affixed to Lohan’s tabloid saga, returns as a compliment. (Spoken by Megan Thee Stallion, whom I have to imagine meant nothing but love.) The film supposes that deviance went extinct, that we already got the message. Explicating a film by what it lacks bores everyone, but lacking norms, even norms to be critiqued, the new Mean Girls lacks a positive identity. The OG is all we have. (And the new Aaron Samuels isn’t even hot!)

The new Mean Girls is also, it should be said, a musical. The songs are not great, it should also be said, though they fit the bill. The film’s directors, Samantha Jayne and Arturo Perez Jr., working with the cinematographer Bill Kirstein, who has directed music videos for Beyoncé, Justin Timberlake, and Orville Peck, know that song and dance numbers require their own visual mechanics. The production is phantasmagoric yet grounded in space, turning a locker-girded hallway or a kegger into a dynamic scene where everyone and everything, down to an aerial stunt or elephantine gesture on the periphery of the frame, does its part. In “I’d Rather Be Me,” a number that sprouts from the middle-finger salute Janis delivers after revealing her revenge plot against Regina, the camera chases behind and around Janis as she runs in and out of rooms where students loaf, exercise, play music—an expertly produced undertaking, and for a character whose epiphany is meant to steer us to the part with the crashing bus.

Thank God for Regina George. Alpha and omega. The irony, though, is that she’s never been less relevant. The girl is low these days. In 2019, after Donald Trump mocked Hillary Clinton’s decision not to run for president again on Twitter, she replied with a gif of Regina George—“Why are you so obsessed with me?”—in what can only be called “loser behavior.” The bosses are, thankfully, down bad. Better, then, to say thank God for Renee Rapp, who as Regina packs enough animal magnetism for everybody. Hopefully she’ll be leveraging this franchise, which has been with her since her Broadway debut at nineteen, into roles worth her salt. She has said that she’s a bit “tired of wearing pink.”

There is one “slut” in the new film. As the Mathletes championship comes down to a final, sudden-death tiebreaker, two beautiful, clear-skinned white girls approach the podium. “Nice to meet you,” says Cady. The other girl sneers, “Whatever, slut.” Cady is taken aback. It is the meanest line of the film, a poison pill slipped via a rando from another school about whom we know nothing. At least the math hasn’t changed.