An empty stretch of road hemmed in by high cement walls. The level tarmac shines with dew. A muezzin is heard over traffic. Signs point toward Rachel’s Tomb and Jerusalem.

Soon a whirring noise picks up. An old man enters the frame reloading his camera. For some two minutes he moves left and right, forward and backward, at times standing tall, at others bending. At last he halts, snaps, spins around beaming. The director cuts to a blank screen, then to the resulting still.

It shows the same view, but the effect is very different. Black and white has aged the cement slabs, which look more weathered. The wide-angle lens has stretched out the scene, paradoxically raising the barriers. A large aperture has let in fresh details: new patterns of dampness have emerged along the walls, the surveillance monitors hanging off them have lit up, a watchtower has resolved into focus in the distance. What seemed drab and slapdash has revealed itself to be planned and sophisticated.

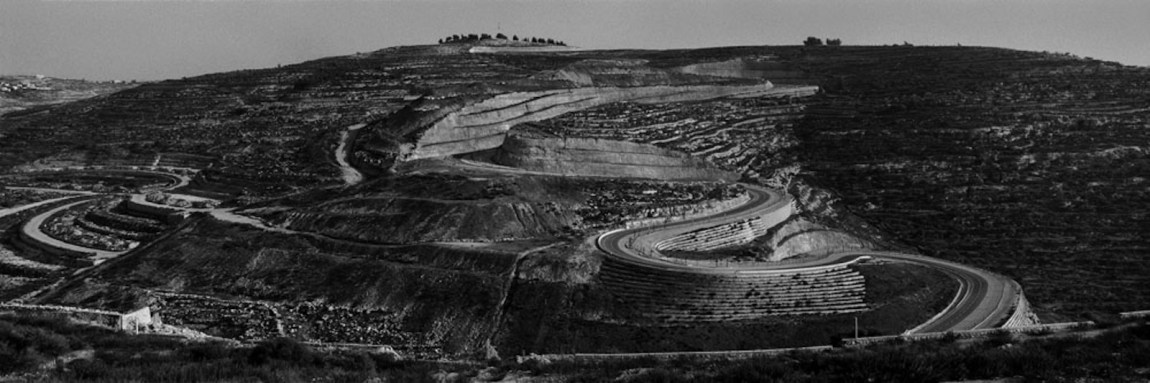

This is the opening sequence of Gilad Baram’s Koudelka: Shooting Holy Land (2019). The documentary observes Josef Koudelka between 2008 and 2012 as he travels across Israel–Palestine and takes pictures of the “separation barrier” that has spread like a web across the territory. It effectively paints a double portrait: of the photographer, who is by turns patient and decisive, serene and troubled; and of the infrastructure of the occupation, which warps the landscape. Many segments close on photographs made by Koudelka. He crawls under a barbed wire fence; the image shows a hilltop settlement through coiled steel. He walks through a field with cardboard cut-outs of soldiers; the image shows them rushing forth in formation. He is led to a wretched hamlet; the image shows huts around a clearing, with a donkey tethered nearby, as in a pastoral.

“I grew up behind the Wall,” Koudelka says at one point. “I wanted to go to the other side.” He was born in Moravia and came of age after the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic had been brought within the Soviet “sphere of influence.” The occupation reminded him of life behind the Iron Curtain. Baram drives the point home by cutting from a picture Koudelka shot in Israel–Palestine to ones he took during the 1968 invasion of Prague. Two images depict tanks: one parked at a memorial to a battalion that fought in the Yom Kippur War and the other abandoned to a protestor who has clambered on top with a Czech flag.

*

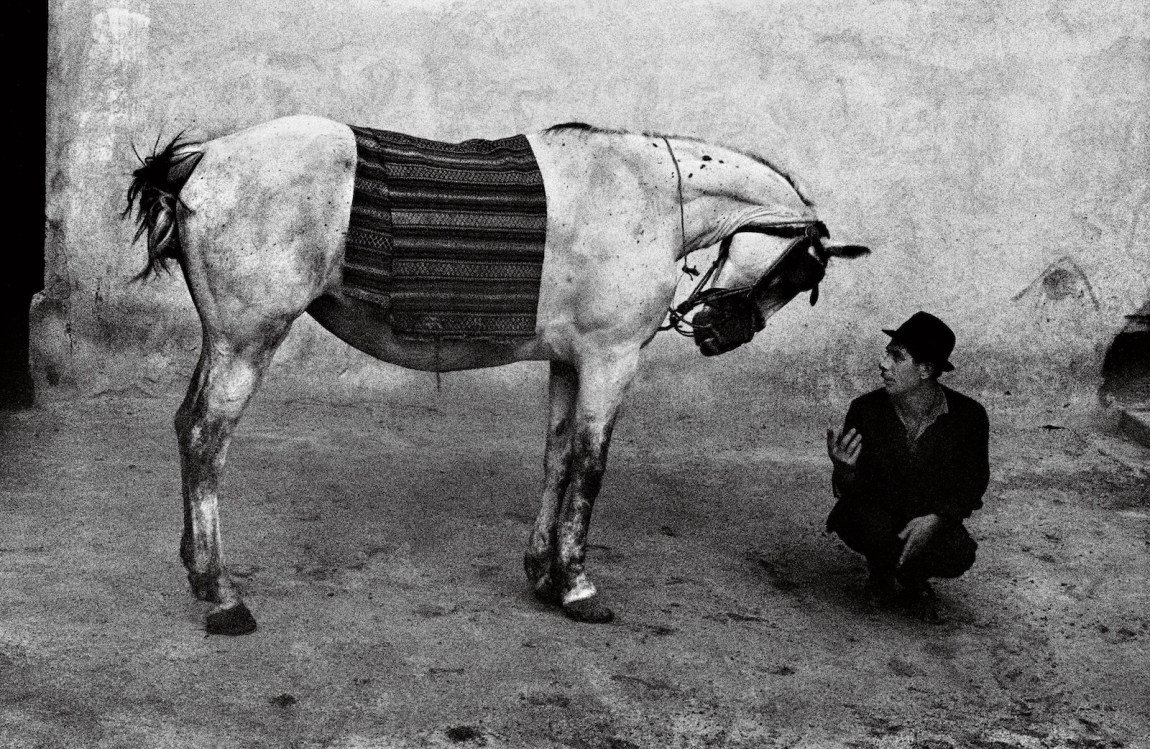

Koudelka has always been a historically minded artist. “I am interested in photographing what is going to finish soon…what is not going to exist anymore,” he has said. He made his first major series in the 1960s at Romani settlements, most of them in Czechoslovakia, which the historian Will Guy notes had “launched an ambitious crash campaign to settle and assimilate Gypsies.” Koudelka met these perpetual outsiders as they were forced inside. His images are forthright and elliptical, charmed and puzzled, pensive and commemorative. Above all, they are radiant with deference towards an unknown way of life. One shows a crouched man in a grubby hat and suit, turned to face a muddy white horse, which bows its head; the two are deep in a conversation from which the viewer is excluded.

Later projects took Koudelka further from home. In the 1970s and 1980s he assembled a pictorial chronicle of his vagabond travels across Europe. The critic Max Kozloff has drawn attention to his “exclusionary genius.” Koudelka kept out “the tourist scene, the life of the middle classes, plastics, the consumer market, signs, cars, modern diversions, blue collar existence, productive systems of any kind, in short the characteristic jamboree of the late twentieth century.” His subjects come from an earlier period: houses of God and pilgrimage sites, farms and country fairs. A tableau shows a young girl staring past an old nun, who smiles down at her; behind them a man looks into the shadows.

In the 1990s Koudelka turned away from people and toward places scarred by human contact. “The wounded landscape…is marked by trouble, by suffering,” he has said. “It is the same as the face of people who have a difficult life.” He photographed factories, mines, and quarries; military occupations and war-torn cities; architectural ruins. His shots are vertiginously wide, with a sharp, dark palette—he has never taken color pictures—and balanced, stately compositions. “One cannot simply use the term beauty [for] these astounding panoramic photographs,” the French philosopher Gilles A. Tiberghien argues.1 Their “pleasure” is “alloyed with sadness, horror, and guilt.” An image from 1994 shows a giant statue of Lenin tied to a barge that floats down the Danube in Romania: Gulliver banished by the Lilliputians.

Advertisement

Today Koudelka is among the most respected living photographers. He has long been a full member of the Magnum Collective, has published many photobooks, and has had solo exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art and elsewhere. All the same he retains the aura of a maverick. “He regularly says no to interviews, teaching, panel talks, and speeches,” Melissa Harris writes in her new “visual biography,” Josef Koudelka: Next. “With one exception, he has never, since going into exile from his native Czechoslovakia in 1970, accepted a commercial or editorial assignment.”

For the most part he has lived peripatetically, travelling through the year, sleeping for weeks on the floor of Magnum’s Paris office. Elliott Erwitt told Harris that Koudelka’s colleagues there called him “Saint Josef”—a joke about his monastic lifestyle. Two images can be taken as self-portraits. The first, made in 1976, shows a meal spread out on a newspaper: pear, baguette, crackers, and cheese. A headline reads: “10 Said Slain in Soweto As Black Strike Holds.” The second was shot in 1987 in a deserted park in Paris, where a black dog races through the snow.

Harris’s book draws on interviews with Koudelka and his acquaintances. She has tracked down friends from his youth, earned the confidence of his romantic partners and children, and probed his Magnum colleagues and fellow photographers. All speak openly—and warmly—of him. Over a hundred small-format pictures are scattered across the text, giving it the feel of a scrapbook. Some are from his oeuvre, others are biographical. Harris refrains from painting a critical portrait of the man or offering an incisive commentary on his work. But she has gathered material that brings readers closer to one of the most intractable oeuvres in the history of photography.

*

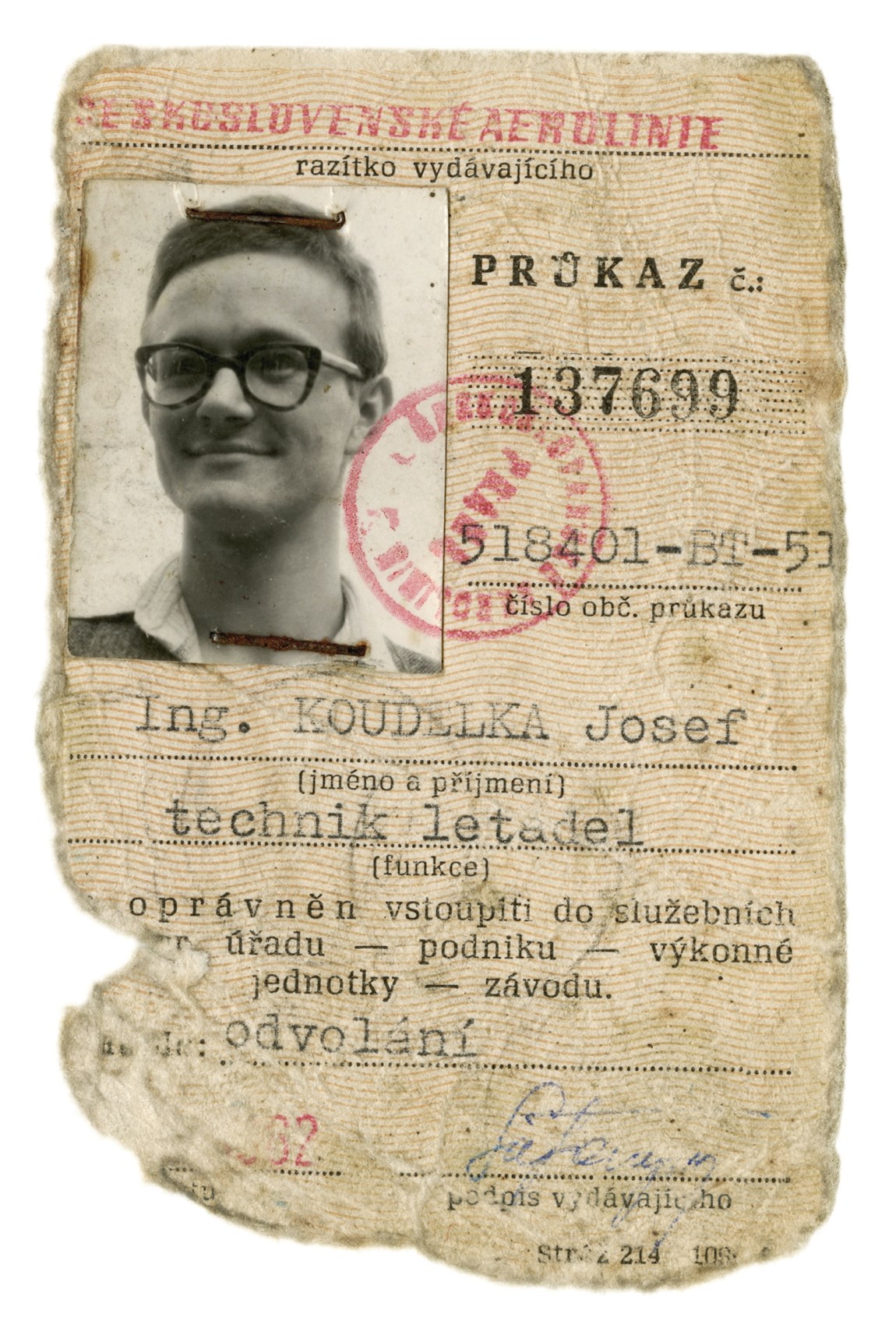

Koudelka was born in 1938 and grew up in a village named Valchov (today in eastern Czechia). His mother ran a grocery store and his father was a tailor. Politically independent-minded, they took food to Partisans who had camped out in the woods nearby during the German occupation, and in 1948 they opposed the Stalinists who then usurped power. Their son learned to think with his hands from a young age. Josef assembled model airplanes, rode a moped, played the violin and accordion. At fourteen he was sent to Prague to attend a school for aeronautical engineering, which he then studied at the Czech Technical University. He graduated in 1961 and was hired by the state airline company.

By this time he was taking photographs in earnest. Self-taught, headstrong, and indifferent to the medium’s history, he proceeded largely by intuition. The camera gave him an excuse to travel; he made pictures on trips to Slovakia, Poland, and Italy, as well as around Prague. “It is striking,” his French publisher Robert Delpire has observed, “that Koudelka’s penchant for a wide format formed as soon as he began photographing, before he could have developed an eye or memory of such unusual compositions.”2 His early work is marked by large empty spaces, with distant figures seen in outline or silhouette. An image made in 1958 on a beach in Poland shows a nun in robes near the right margin, looking down at sand that extends across the frame.

From 1962 to 1969 Koudelka freelanced for a theater monthly. His playhouse images are dreamy, grainy, often poorly lit, and always in the thick of things. He favored close-ups and portraits. In 1965 the avant-garde troupe Divaldo za branou (“Theater Beyond the Gates”) hired him; he quit his job at the airline two years later. Koudelka was allowed to walk among the performers and shoot as they rehearsed. An extreme close-up from a 1966 production of Chekhov’s Three Sisters shows a man and woman (presumably Andrei and Natasha) cheek to cheek, his eyes tenderly closed in love, hers deviously looking away.

It’s not clear what led Koudelka to make a project on the Romani. He was certainly drawn both to their footloose lifestyle and their folk music.3 Perhaps he also felt a kind of historical curiosity. “All but a few hundred” of the 6,500 Romani in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, Harris notes, were murdered in Nazi camps. The far larger population in Slovakia, however, mostly survived. This was where, in 1962, Koudelka first hiked out to a settlement. “There was this big plain and in the background were the High Tatra mountains covered with snow,” he told Harris. “In the distance I saw these wooden cottages and I heard a lot of noise. I summoned my courage and decided to go there.” Over six years he sought out Romani groups across eastern Slovakia as well as some in Bohemia, Moravia, Romania, Croatia, and Hungary. These trips formed the basis of his debut photobook.

Advertisement

Gypsies (1975) defies categorization. It is “neither documentary, ethnography, nor traditional reportage,” the book editor Stuart Alexander argues.4 “It was his personal vision.” Koudelka paid repeated visits to his subjects, stayed with them at length, won their trust if not quite their friendship. They had something to gain from him as well. Some had never been photographed and asked to pose for mementos. “It was theater too,” Koudelka recalled decades later. “The difference was that the play had not been written and there was no director—there were only actors…all I had to know was how to react.”

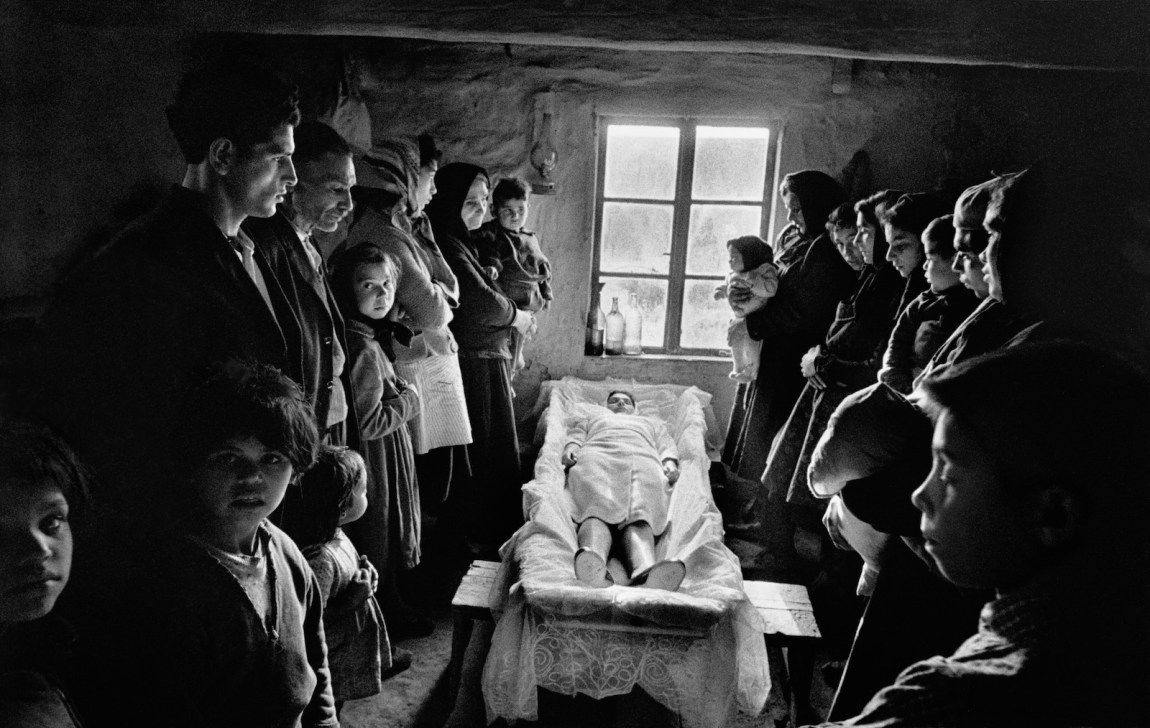

Most of the pictures are portraits or tableaux. Many are shot in unlit rooms, with high-speed film and a wide-angle lens. They waver between concealment and disclosure. In one sense they offer a great deal of information. The Romani live in ramshackle huts, wear filthy clothes, eat on the floor. Their quarters are both empty and cramped, with, at best, a portrait of Christ on the wall. An image made in 1963 in Kadaň (today in Czechia) looks out from the living room, where a weary patriarch turns toward the camera, and into a bedroom where nineteen children are gathered, some seated and others standing, in front of a man and woman who are presumably their parents. The settlements are extremely remote. A pair of images made in 1965 and 1968 in Vinodol (today in Croatia) show rudimentary outhouses against a backdrop of vast plains. Funerals recur. An image made in 1963 in Jarabina (today in Slovakia) shows an ornate casket carried by four men, who are followed by a small procession; they tramp in their Sunday finest through muck.

At the same time Koudelka makes visible how little he understands about the Romani. His unstaged pictures are rich in oblique drama. A young girl in a sparkling white dress poses with flowers in front of a crumbling wooden house with two grimy windows, through which two older women peer out, frowning. Do they disapprove of her impropriety, or would they like to be in her place? A child runs between brick houses carrying a wooden cross; why away from a matron who turns in concern and towards an uninterested younger woman? The village has assembled in the far distance to watch the police arrest a man, who stands alone in handcuffs in the near ground. Is he forever banished, or will they take him back?

Perhaps Koudelka’s most eloquent image of doubt was made at the funeral in Jarabina. In a dingy room with a low ceiling, mourners stand on either side of an open casket, in which a young woman has been laid to rest. Light streams in through a window on the far wall and picks out their downcast faces. They are at once together and apart, each grieving in their own way. At the corner of the frame, a child turns to the camera aghast.

*

Photographs from the Romani series were exhibited in Prague in 1967. The party had already taken notice, invited Koudelka to a private meeting, and advised dropping the subject, which was presumably too backward for a vanguard nation. He was soon facing more serious trouble. In the mid-1960s, taking a cue from Khrushchev, the Czech Communist Party began its own piecemeal liberalization process. Political prisoners were freed; business enterprises were given leeway; restrictions on travel were loosened. When Alexander Dubček was elected to lead the country in January 1968, he promised more significant reforms, including to lift press censorship and federate the republic into Czech and Slovak nations. Brezhnev warned Dubček that “socialism with a human face” was a counterrevolutionary enthusiasm, and “negotiations” between the two parties soon broke down. On August 20 Warsaw Pact forces—of the USSR, Poland, East Germany, Hungary, and Bulgaria—invaded a fraternal socialist nation.

Koudelka, like everyone else, was caught unawares. He was woken up at 4:00 AM by a friend’s terrified phone call and soon heard the military planes. By mid-morning he was out taking pictures. “I found myself facing something bigger than myself,” he remembered. “There wasn’t time to reason, but it was my life, my story, my country, my problem.”5 In a week he shot roughly ten thousand photographs. He prowled the streets, moved amid protestors, confronted soldiers, walked up to tanks, climbed on top. Today he plays down his courage, but the British photojournalist Ian Berry suggests otherwise. “I saw…an absolute maniac who had a couple of old-fashioned cameras on a string round his neck and a cardboard box over his shoulders,” he recalled. “He had the support of the crowd, who would move in and surround him whenever the Russians tried to take his film. I felt either this guy was the bravest man around or he is the biggest lunatic around.”

Invasion 68: Prague (2008)6 stands apart in Koudelka’s oeuvre. It is densely rather than sparsely peopled, conveys motion rather than stillness, features upright rather than slanted incident. Everywhere the focus is on expressions and gestures. An image shows an adolescent raising his fist provocatively close to infantrymen sitting on a tank. Another shows a man waving a flag in a soldier’s face. One looks from the front at a nighttime demonstration; a portrait on a raised banner of the student martyr Jan Palach glows in the darkness. “Koudelka’s photographs capture a trapped population coming to consciousness,” the Czech poet Petr Král argues. They deal “with individuals who emerge from imposed anonymity by discovering their own sense of revolt.”

Koudelka’s treatment of the soldiers is more complicated. He casts them less as trained killers than as truant schoolboys making fools of themselves under the steely gaze of civilians. Many images show tanks brought to a halt by protestors. In one a behatted general comes out from the porthole and looks on sheepishly as a young woman admonishes him. “They were completely confused,” Koudelka told Harris. “They were surprised that the Czechoslovaks didn’t want them there.” In another an older woman leans against a flatbed truck and seems to reprimand the infantrymen sitting on top. “It is not important in [the pictures] who is a Russian and who is a Czech,” Koudelka clarified. “What is important is who is holding a weapon and who isn’t. The one who isn’t…is actually the stronger.”

The 261 film rolls had to be kept hidden. In September Koudelka made a batch of prints and smuggled them out to London, where The Daily Telegraph Magazine turned them down. Another set of negatives had been lost. Finally, in August 1969, to mark the one-year anniversary of the invasion, the Sunday Times Magazine published a handsome spread, attributed to “a Prague Photographer.” By this point Erwitt had spotted a potential Magnum recruit and was helping Koudelka get out. In October the collective awarded him a fellowship, which in turn got him an eighty-day exit visa. In 1970 he was granted asylum in the UK. Harris quotes an interview in which he recalled making the decision: “I had no desire to go to jail. So I decided to accept what had happened, not to return, and do what I was unable to do in Czechoslovakia: see the world.” He stayed away for twenty years.

Koudelka took well to statelessness. “Never stay for a long time in one place,” he wrote in his diary. “When you go from one place to another place, you are cleaning yourself.” Throughout the 1970s he lived with a rotating cast of Magnum affiliates in London, where David Hurn was his main host, after which he relocated to Paris, where Henri Cartier-Bresson became a champion and benefactor. Mostly, however, he travelled around Europe. Averse to cities, he wandered the countryside in search of surviving folk customs. “He arranged his life…around the dates of important Roma festivals and religious events,” the art historian Amanda Knox notes: Semana Santa in Spain, Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer in France, Traveler horse fairs in England, Reek Sunday in Ireland.7 Many nights he slept outdoors: “There is nothing more beautiful than to sleep under the stars,” he told Harris. “To look at the sky and wait until you see Vega.”

Delpire gave Koudelka’s next photobook a somewhat misleading title. Exiles (1988) includes pictures shot over two decades across the continent: England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales; France and Switzerland; Spain, Italy, and Portugal; Greece and Turkey; Romania, Serbia, and Croatia; and a couple from Czechoslovakia. The photographs fall in two categories. The first are stylized and ambiguous tableaux that pick up where Gypsies left off. An image made in 1971 at a small-town square in Spain shows suited men with handicraft rockets. One has just released the firecracker; its smoke blurs his figure, as if hinting that this pastime will soon fade away. Another made in 1973 in France shows three Romani youth playing pétanque: one tosses the ball in the air, the second is about to roll, and the third lies on the grass. Deliberation, practice, and action.

The second category is more vexing. These pictures are expressionistic in form with idiosyncratic and often unsettling subjects.8 They come in different types. Portraits of animals in distress: a tortoise tipped on its shell, a chained monkey scratching itself, a cat running down a brick wall. Portraits of outcasts: a homeless man asleep on a park bench, a disabled man walking down a cobblestone path, a hunchbacked maidservant wiping down a door. Dour still lives: canvas falling off a packing crate, a bundle of damp timber, newspapers strewn down the stairs. Vacant scenes: afternoon shadows on a deserted by-lane, a rearview mirror against sandy fields, an empty café. “The same mastery over the transient exists throughout,” the Lebanese novelist Dominique Eddé writes.9 “The same invasion of absence, the same blow of the bludgeon, the same solitude, the same muteness.” The book’s black humor can leave a bitter taste in the mouth. A tableau made in 1976 in Ireland shows men in overcoats peeing in formation along a cement wall. It’s not clear who the joke is on.

*

Cartier-Bresson did not quite approve of the landscape photographs Koudelka turned to making in the late 1980s. “But where are the people?” he asked. That question trailed Koudelka as he withdrew ever further from “the characteristic jamboree of the late twentieth century.” His work moved in two directions. On the one hand he sized up massive infrastructure projects: dockyards in Wales, the Sollac steel plant and Lhoist limestone quarry in France, coal mines in the “Black Triangle” region bordering Germany, Poland, and Czechia. On the other hand he pictured ruins: mainly those from antiquity in the Mediterranean basin but also buildings destroyed in the Lebanese and Yugoslav Civil Wars.

The pictures in Chaos (1999) are made in a panoramic format, often in a three-to-one width-to-height ratio, of the kind generally reserved for high-altitude vistas. As the physical world recedes, viewers are invited to contemplate rather than enter the frame. An image made in 1999 in the Black Triangle surveys a power plant. Furnaces arrayed in a line on the far horizon spew out smoke, sagging electrical lines run down the right frame, a freight train edges in from the left, and the bulk of the near ground is covered by stony wasteland, out of which a severely bent lamppost rises. The scorched earth looks bereft of all vitality, no longer able to sustain life, in arresting contrast to the industrial facility, which hums along inexorably, in a state of disrepair. Even the simpler pictures can be perplexingly absorbing. An image made in 1989 in Nord Pas-de-Calais shows hulking, polyhedral wave breakers against a sky heavy with rain clouds. The play of textures and pervading traces of water throw the stones’ density into relief.

Tiberghien has described the terrains Koudelka chose as “entropic.” Here order gives way to disorder. That idea applies best to his studies of war. In 1991 in Beirut an old couple pull at hookahs in a room with a missing front wall; the other half of the building has been blown apart. In 1992 in a cemetery (presumably Orthodox) in Vukovar, the lopped-off marble head of Mary is placed on a broken cross.

Koudelka reprises the theme in a different key in Wall (2013). Its somber, restrained, unflinching pictures reveal how Israel’s barrier has desecrated one of the holiest regions on earth. An image shows cars winding along a sandy hillside; the road runs along a fence that demarcates Sawahira ash Sharqiya from Sur Bahir. The territories were, a caption informs us, separated in the Nakba, “‘reunited’ following Israel’s conquest of East Jerusalem” in the Six Day War, and divided again after the second intifada. An image near Bethlehem shows agricultural land scratched up across the near ground; villages lie behind fences on slopes that ascend on either side. Hardhatted construction workers can be spotted through the felled vegetation. The base of a chopped tree rises in the middle of the frame.

*

Koudelka stands at an angle to the documentary tradition. He got his start when Cartier-Bresson’s concept of “the decisive moment” was the disciplinary common sense, at least in western Europe and the US. The idea was to sum up the present, catch society in motion. Artists as different as Helen Levitt, Robert Frank, and Garry Winogrand set sail under this flag. From behind the Iron Curtain, Koudelka charted a different course. Turning away from novelty and taking the longer view, he composed deliberative and mysterious images that nudge the viewer to acknowledge, or to imagine, what lies beyond the frame, in time and in space.

He tends to speak about his work in formal terms. “Cartier-Bresson, through painting, got to photography,” he has said. “And I got, through photography, to painting.” But the viewer might be tempted to see his pictures in a historical light, indeed to see them as casting light on history. Throughout his career he has charted forms of social upheaval, while pausing to memorialize, with respect but without nostalgia, people who resist the notions of progress imposed upon them. A line can be drawn between the image he made in 1958 of the nun on the Polish beach in her black robes and veil, and another, which he shot over half a century later in the West Bank, where an old man in a gown and keffiyeh stands atop the ruins of a building, presumably his house, which has been demolished for lacking the right “permit.”

Is it ironic that Koudelka is best remembered for a photograph that includes a time stamp? At noon on August 22, 1968, two days after Warsaw Pact forces entered Prague, he and another man, Milan Jîlek, climbed a building overlooking Wenceslas Square, which was deserted: the party had called a general strike. To mark the occasion, Jîlek stretched out his arm, sporting a bulky wristwatch, which Koudelka shot against the empty backdrop. The image is jarring and poker-faced. Two timelines coexist within it: that of an individual life, governed by the watch, and that of the nation, which plays out in the square. As is often the case in Koudelka’s photographs, private memory and public history have momentarily converged.