In the days that followed Hamas’s heinous October 7 attack on military bases, kibbutzim, towns, and the Nova music festival, several high-ranking Israeli officials announced that they intended to deprive Gaza’s civilian population of its most basic needs. At the time, over 80 percent of the goods entering the Gaza Strip came from Israel, which has kept the area under strict blockade for seventeen years. On October 9, following two days of extensive aerial bombing, the country’s minister of energy and infrastructure, Israel Katz, announced that he had ordered water, electricity, and fuel to be cut off. “What was,” he said, “will not be.”

The same day, the defense minister, Yoav Gallant, demanded a “complete siege” of the enclave: “there will be no food, there will be no fuel.” (His reasoning has since become notorious: “we are fighting human animals.”) On October 17 the national security minister, Itamar Ben-Gvir, insisted that “as long as Hamas does not release the hostages in its hands…not an ounce of humanitarian aid” would enter Gaza—only “hundreds of tons of explosives from the Air Force.” The next day Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu put the matter in similarly stark terms: “We will not allow humanitarian assistance in the form of food and medicines from our territory to the Gaza Strip.”

These were all declarations of an intent to deprive the Palestinians in Gaza “of objects indispensable to their survival, including willfully impeding relief supplies”—the legal definition of “using starvation of civilians as a method of warfare,” a crime against international law under the Rome Statute. Israeli newspapers, television, and social media, meanwhile, were saturated with calls to destroy the population, in whole or in part: to “erase” Gaza, “flatten” it, turn it “into Dresden.” On October 13—the day that Israeli authorities ordered 1.1 million people in northern Gaza to evacuate their homes within twenty-four hours—the country’s president, Isaac Herzog, said publicly that there were “no innocent civilians” in the Strip.

Since then, the Israeli military has carpet-bombed entire neighborhoods, killing over 32,000 Palestinians, of whom more than 13,000 are children (these numbers do not include people lost under the rubble). More than 74,000 residents have been injured. Seventy percent of civilian infrastructure has been destroyed or damaged, leaving many areas uninhabitable. As of November, over 75 percent of Gaza’s population, some 1.7 million people, had already fled their homes; many have been forced to move repeatedly.

The army has systematically attacked dozens of health care facilities, leaving one in three hospitals in Gaza partially functioning and forcing doctors to operate under severely inadequate conditions on a constant stream of injured civilians, many of them children. This level of killing and destruction in such a short time is unprecedented in the twenty-first century. The UN special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian Territories, Francesca Albanese, concluded earlier this week that “there are reasonable grounds to believe” that Israel has crossed the threshold of genocide.

Meanwhile, far too many aid deliveries remain blocked. The aid that makes it into Gaza is, as UN agencies have warned, “a mere drop in the ocean of what is needed.” To date, Israel has allowed, on average, 112 trucks to enter a day, less than a quarter of the number that entered daily in the months before October 7, when needs were significantly less acute. In mid-January, after reports emerged that the Israeli military was obstructing aid shipments, especially to areas north of Wadi Gaza, a dry river valley that separates the northern and southern halves of the Strip, Netanyahu insisted that his government would allow only the “minimum” aid necessary to prevent a humanitarian crisis. In the six weeks before February 12, the authorities denied access to 51 percent of missions planned by humanitarian organizations to deliver aid to the north.

These restrictions have severely diminished the ability of humanitarian workers to distribute aid, as have threats to the safety of humanitarian personnel and sites themselves. Philippe Lazzarini, the commissioner-general of the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), recently noted that his organization, “the main lifeline for Palestine Refugees, is denied from providing lifesaving assistance to northern Gaza.” Since October 7 at least 171 UNRWA team members have been killed. On several occasions Israeli forces have fired on UN trucks carrying food supplies along routes the military itself had designated safe, destroying the aid and suspending the deliveries. At other times Israeli troops have killed Palestinians waiting to receive aid: in one instance, which has become known as the flour massacre, at least 112 people who had gathered to collect flour in Gaza City were killed. By late February UNRWA announced that it had been forced to pause aid deliveries to the north.

Israel has not been content with preventing food from entering the Strip. Since the war began it has also destroyed more than one third of Gaza’s agricultural land, more than one fifth of its greenhouses, and one third of its irrigation infrastructure—all vital sources of food. Forensic Architecture claims that “the destruction of agricultural land and infrastructure in Gaza is a deliberate act of ecocide.” Large swathes of that land were razed by soldiers using D9 bulldozers and explosives to expand the “buffer zone” on Gaza’s side of the border from three hundred meters to an estimated eight hundred meters, reducing the Strip’s area by 16 percent. Israeli naval forces have also damaged or destroyed around 70 percent of Gaza’s fishing vessels. Driven by hunger, a few fishermen still go out to sea in small vessels, risking the wrath of naval forces; some of them, as the fishermen’s association in Gaza reports, have been attacked and killed.

Advertisement

*

The effect of these actions is clear. Since December aid agencies have warned that Palestinians in both halves of Gaza are at risk of famine, the most catastrophic form of food insecurity tracked by the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC). In a UN-backed report published on March 18, a committee of experts offered a dire prediction. “Famine,” they reported, “is now projected and imminent” for 70 percent of northern Gaza’s population—around 210,000 people—and “expected to become manifest” by May. Witnesses describe people there grinding grains used for animal feed into flour, and when animal feed ran out, residents fed grass to their emaciated children.

According to UNICEF, malnutrition among children is spreading fast and reaching unprecedented levels. As of March 15, in northern Gaza, one in three children under two are suffering from acute malnutrition; at least twenty-seven children have reportedly died from starvation. The previous month nutrition screenings conducted by UNICEF and other organizations found, in the organization’s words,

that 4.5 percent of the children in shelters and health centers [in northern Gaza] suffer from severe wasting, the most life-threatening form of malnutrition, which puts children at highest risk of medical complications and death unless they receive urgent therapeutic feeding and treatment.

Due to Israel’s attacks, however, this treatment is no longer available in Gaza. UNICEF added that in the month before the report appeared, “the prevalence of acute malnutrition among children under five years of age in the north [had] increased from 13 percent to as high as 25 percent.”

In March, screenings the organization conducted in the middle area of the Strip found that 28 percent of children under two have acute malnutrition; of that group, more than 10 percent have severe wasting. In Rafah, a designated safe zone on the southern border where workers have managed to deliver slightly more aid, screenings showed that the number of acutely malnourished children under two doubled from 5 percent in January to about 10 percent by the end of February. (Despite its nominal status as a safe zone, Rafah itself has been repeatedly bombed.) Among the same group severe wasting rose fourfold over the past month, to more than 4 percent.

Malnutrition among pregnant and breastfeeding women has also increased rapidly. As of February 2024, 95 percent of such women now face severe food poverty. Because mothers who suffer from malnutrition are unable to produce enough milk to breastfeed, more infants must depend on formula milk for survival. But formula requires safe and clean water, which is not available to most mothers—in turn increasing the risk of infection and malnutrition.

All this suffering is human-made, a direct outcome of Israel’s unrelenting barrage. Like most famines, it is also the product of a longer history. Since 1967, when Israel first occupied the Gaza Strip, it has controlled the Palestinian food basket, engineering the nutritional intake of its inhabitants and using food as a weapon to manage the population. For decades Israel has systematically damaged the Strip’s capacity to produce its own foodstuffs, decreasing its access to drinkable water and nutritional food. Understanding these longer-term policies is crucial for making sense of the famine unfolding in Gaza now.

*

The Gaza Strip is a flat, narrow, arid region extending some twenty-five miles along the Mediterranean coast. When Israel occupied it, at least 385,000 Palestinians lived there, of whom around 70 percent were refugees, having fled or been expelled from their homes during the Nakba (catastrophe) of 1948. Israel immediately, as one of us, Neve Gordon, wrote in a 2008 study of the occupation, “assumed control over all major utilities, such as water and electricity, and took over the welfare, health care, judiciary, and educational systems.”1

It also introduced a variety of surveillance mechanisms to manage the newly occupied population. Israeli authorities counted televisions, refrigerators, gas stoves, livestock, orchards, and tractors; inspected and often censored school textbooks, novels, and newspapers; made detailed inventories of factories for furniture, soap, textiles, olive products, and sweets; used satellite and aerial images to monitor the construction of homes, public buildings, and private businesses; and gathered demographic data across the region, including of urban versus rural and refugees versus permanent residents. They scrutinized the infant mortality rate, the population’s growth rate, poverty levels, per capita income, and the size and makeup of the labor force: age, gender, and field of occupation. They also paid close attention to the scale and type of industry in the territories, as well as the amount of arable land, the kinds of crops planted, and the number of cattle and poultry. To entrench its control Israel also tracked the rate of private consumption and the nutritional value of the Palestinian food basket.

Advertisement

The resulting official reports illustrate the speed and degree of surveillance to which Israel subjected Palestinian society. Strikingly, they show that in the late 1960s and 1970s the military government tried to increase the per capita nutritional intake of Gaza’s residents. In one study the Israeli Agriculture Ministry boasted that a series of interventions, including vocational training programs for farmers, had raised the per capita consumption of the average Palestinian in Gaza from 2,430 calories per day in 1966 to 2,719 calories in 1973. A different report notes that in 1968 Israel helped Palestinians in the Strip plant some 618,000 trees and provided farmers with improved varieties of seeds for vegetables and field crops. Contrary to the Agriculture Ministry’s report, however, the major catalyst for the improvement in the population’s standard of living was not the benevolent allowances of an occupying force but, rather, the remittances that flowed into Gaza’s economy from the early 1970s, after Israel incorporated over 30 percent of the enclave’s laborers into its construction and agricultural sectors in the interest of extracting cheap labor.

Israel’s State Archives make clear that these initiatives were designed to normalize the occupation and appease the population. In 1973 many of the refugees in Gaza were still living in camps under squalid conditions. That year Moshe Dayan, then Israel’s defense minister, proposed moving them into “new towns, in apartments with water in the faucets, education and services for the children.” The rationale was less humanitarian than strategic. “As long as the refugees remain in their camps,” he explained, “their children will say they come from Jaffa or Haifa; if they move out of the camps, the hope is that they will feel an attachment to their new land.”

*

Israel began reversing these policies after the outbreak of the first Palestinian intifada in December 1987. In the years that followed, limiting nutritional value and creating food insecurity among Palestinians in Gaza became central to the state’s counterinsurgency strategy.

Changes on the ground were incremental. In 1989 Israel enforced stricter control over the flow of laborers from Gaza by issuing magnetic cards with coded information about the worker’s “security background,” taxes, and electric and water bills. Shortly afterward, during the first Gulf War, it imposed what the UN and human rights organizations call a “hermetic” closure on the Strip, further limiting the movement of people and goods. In 1994, between the signing of the first and second Oslo Accords, it began building a thirty-two-mile-long fence and patrol road around the territory.

Ever since, just five passageways have connected the two regions, two of which only operate in one direction, allowing goods and people from Israel into Gaza. A sixth—the Rafah crossing—connects Gaza with Egypt. Throughout the 1990s restrictions were imposed on the number of laborers who could enter Israel and the amount and type of goods that could enter Gaza. This was also when the Green Line, the internationally recognized border between Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories, was converted from a “normally open” border into a “normally closed” one.

In the aftermath of the second Palestinian intifada in September 2000, Israel made a complete volte face from the policies it had implemented in the late 1960s and 1970s. As part of its efforts to clamp down on resistance, the military destroyed farms, razed more than 10 percent of Gaza’s agricultural land, and uprooted more than 226,000 trees. Around this time it also consolidated its control of Gaza’s air and sea, bombing the airport built in 1998 as part of the Oslo Accords and, in 2002, destroying a seaport that a Dutch–French consortium had been building as part of the agreements reached in the 1999 Sharm El-Sheikh Memorandum. Israel also restricted the areas in which Palestinians could fish to a very small swathe of sea off the coastline, dealing a terrible blow to one of the pillars of Gaza’s food system. Such practices, combined with ever more severe restrictions on the movement of people and goods, led to substantial food insecurity. In 2002 Clare Dyer, writing for the British Medical Journal, reported that the number of children in Gaza suffering from malnutrition had doubled within two years.

*

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon was starting to recognize that it was no longer feasible to deploy hundreds of Israeli soldiers to secure the eight thousand Jewish settlers in the Strip. He also thought that by implementing a unilateral “disengagement plan” Israel could present itself as having deoccupied Gaza. That in turn would help separate Gaza from the West Bank in the public imagination and allow Israel to fortify its West Bank settlements.

In 2005 the Israeli government dismantled the illegal settlements in Gaza and redeployed its troops to the border. At the same time, it intensified its control of the enclave from a distance, building military bases just outside the Strip, setting up remotely controlled machine guns on watchtowers, increasing the use of drones, and establishing a buffer zone 150 to 500 meters wide that eats up agricultural land and mandates that farmers limit themselves to short leafy crops like spinach, radish, and lettuce, presumably to avoid blocking the soldiers’ views.

Around this time, Israel began drawing up lists of products that could not be imported into Gaza, imposing severe restrictions on commercial and humanitarian goods. In 2006, when the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights and other organizations from Gaza highlighted how Israel’s regulations had created shortages of flour, baby formula, and medicine, Dov Weisglass, an adviser to Israel’s prime minister, explained the government’s policy: “The idea,” he said, “is to put the Palestinians on a diet, but not to make them die of hunger.” Even as these restrictions increased poverty and engendered food insecurity, the government in Jerusalem absolved itself of all responsibility. In line with the wording of Israel’s unilateral “disengagement plan”—which avers that following the withdrawal of its troops “there will be no basis for claiming that the Gaza Strip is occupied territory”—the country’s state attorney has maintained that Israel no longer bears any duties as an occupying power.

In reality, Israel continued to exercise its prerogatives by controlling the borders. Following Hamas’s takeover of the Gaza Strip in September 2007, the state formally imposed a blockade, locking 1.5 million residents into a region that was already among the most densely populated on earth. As part of its guidelines on implementing the blockade, the Israeli Security Cabinet instructed the military and other agencies “to reduce the supply of fuel and electricity.” Only goods essential for survival would be allowed to enter.

Israel hardly hid its efforts to engineer malnutrition in Gaza. Writing in these pages last December, Sara Roy quotes a cable sent from the US embassy in Tel Aviv to the secretary of state on November 3, 2008: “As part of their overall embargo plan against Gaza,” it notes, “Israeli officials have confirmed to [embassy officials] on multiple occasions that they intend to keep the Gazan economy on the brink of collapse without quite pushing it over the edge.” Only basic types of goods were allowed entry, mainly medical equipment, medicine, and essential hygienic and food products. Banned foods included chocolate, coriander, olive oil, honey, and certain fruits—all of which Israel characterized as “luxury items.” The quota of fresh meat for the entire population was set at three hundred calves per week.

In 2008 an agribusiness company in Gaza filed a petition in the Israeli supreme court challenging this last restriction. The state attorney responded that the government had calculated that Gaza’s residents needed precisely three hundred calves a week to satisfy their humanitarian needs. In keeping with its long-standing tradition on questions of basic Palestinian human rights, the court declined to intervene.2

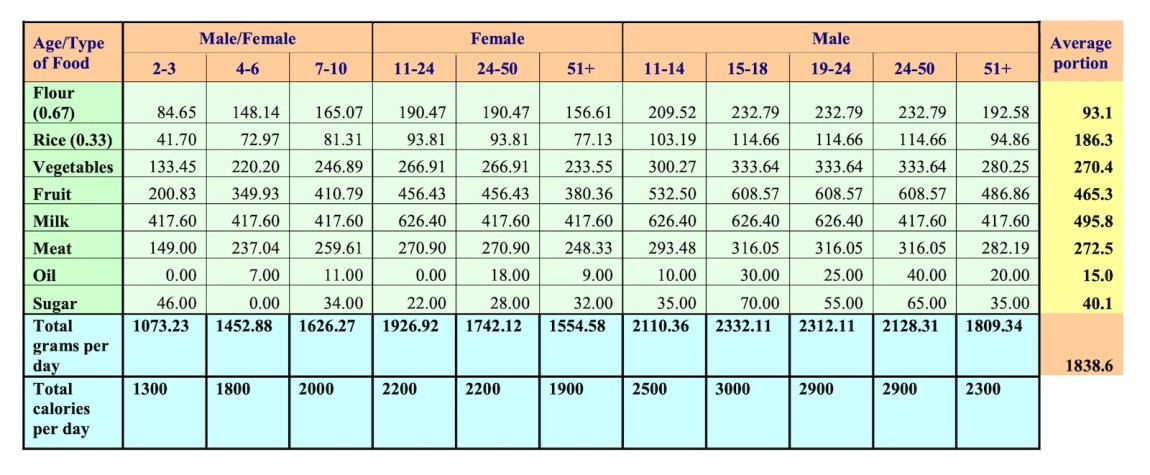

Soon after, the human rights organization Gisha—for whom one of us, Muna Haddad, has worked as a lawyer—began what became a three-and-a-half-year-long legal fight to declassify records showing that Israel had devised a range of mathematical formulas to determine the quantity and types of food that it would allow into Gaza. In 2012 the group won the release of a Ministry of Defense document, based on a model produced by staff in the Ministry of Health, called “Food Consumption in the Gaza Strip—Red Lines.” It includes tables and charts breaking down daily food consumption by sex and age and calculating the minimum caloric intake that would allow “nutrition that is sufficient for subsistence without the development of malnutrition.”

The document assumed that Palestinians in Gaza would be able to import only limited quantities of “basic food items,” such as flour, rice, oil, fruit, vegetables, meat, fish, powdered milk, and baby formula, which Israel calculated could be delivered with seventy-seven trucks a day. Adding medicine, medical equipment, and hygiene and agricultural products, the number of trucks allowed entry daily, five days a week, reached 106—plus sixty truckloads’ worth of wheat per week via a conveyor belt at Karni Crossing, bringing the total number of truckloads allowed to 118 daily. Such calculations took for granted that the food entering Gaza would be distributed equally among the population, an assumption with no precedent in any historical or geographical setting. Israel assumed, too, that only 10 percent of the population’s dietary needs would be met by fruits and vegetables produced in Gaza—an implicit admission of how thoroughly the state had come to control Palestinians’ lifelines.

*

These calculations were based on “regular times.” Yet in every major cycle of violence—of which there have been five since 2008—Israel has dropped the “minimum” dramatically, leading to spikes in malnutrition. More than two weeks into the 2008–2009 war, Human Rights Watch reported that “bakeries had not received wheat flour since the beginning of Israel’s ground operation, and only nine out of forty-seven bakeries in Gaza were operating.” That August, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) documented that roughly 75 percent of Gaza’s population was considered food insecure. The main causes, it noted, were “the increase in poverty, the destruction of agricultural assets and the inflation in prices of key food items.” This war, compounded by Israel’s blockade, precipitated “a gradual shift” in the diets of Gaza’s residents, from protein-rich foods to low-cost and carbohydrate-rich foods, “which can lead to micro-nutrient deficiencies, particularly among children and pregnant women.”

In 2010 the Mavi Marmara—the flagship of a flotilla, piloted by Pro-Palestinain activists, carrying 10,000 tons of aid—made an attempt to challenge the blockade and deliver humanitarian aid into Gaza. On May 31 Israeli forces attacked the ship and killed ten of the activists on board, inspiring widespread outrage. Several weeks later, hoping to improve the country’s image, the security cabinet issued a plan to ease the strictures on what civilian goods could enter Gaza. Now items like ketchup, chocolate, and children’s toys were allowed, but the authorities still prohibited thousands of “dual-use” items that could be used for both civilian and military purposes. The dual-use list is broad and vague, encompassing cement mixers, materials required for repairing fishing boats, fertilizers, plastic containers for plants, and pumps for watering them.

It also includes items necessary for ensuring the quality of water and sanitation infrastructure, which needs to be repaired after each round of attacks. In October 2021 the Global Institute for Water, Environment and Health and the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor warned the UN’s Human Rights Council that the Strip’s residents hardly had any access to clean water:

It’s now well established that 97 percent of Gaza’s water has become contaminated; a situation made substantially worse by an acute electricity crisis that stifles the operation of water wells and sewage treatment plants, leading about 80 percent of Gaza’s untreated sewage to be discharged into the sea while 20 percent seeps into underground water.

Palestinian civilians, they continued, are “caged in a toxic slum from birth to death…forced to witness the slow poisoning of their children and loved ones by the water they drink and likely the soil in which they harvest.”

In other words, well before the current war, Israel had rendered the majority of Gaza’s inhabitants destitute and undernourished. Newborn children were seven times likelier to die than if they had been born an hour’s drive away in Beersheba or Tel Aviv. In 2021 Gaza’s per capita GDP reached around $1,050, compared with Israel’s $52,130. It is hardly surprising, then, that in 2022 UNRWA supplied food to over 1,139,000 refugees in Gaza—fourteen times more than it had in 2000. That December UNRWA reported that 81 percent of the refugees in the Strip lived below the national poverty line. It also noted that 85 percent of households purchased leftovers from the market and 59 percent sought assistance or had to borrow food from relatives. More than three quarters of families were reducing both the number of meals they ate each day and the quantity of food in each meal.

*

Since the start of the current war, Israel might have had an interest in getting aid to Palestinians, if only to conceal the violence its military is committing. Instead, as the food crisis in Gaza accelerated, the government launched a concerted campaign to eliminate UNRWA. Already in January, as Amjad Iraqi recently reported in these pages, the Knesset’s subcommittee on foreign policy and public diplomacy had been debating how to deal with the agency. He cites a Kohelet Policy Forum researcher named Noga Arbell: “It will be impossible to win the war if we do not destroy UNRWA, and this destruction must begin immediately.”

Accusing twelve UNRWA staffers of direct involvement in the October 7 attacks and more than a thousand of vaguely defined involvement with Hamas or Palestinian Islamic Jihad, Israel promptly asked all foreign governments to defund the agency. With 13,000 workers in Gaza, UNRWA is the Strip’s second-largest employer, after the Hamas government. Not only does it provide services to over 1.78 million registered refugees, it “pumps $600 million annually into the Strip’s $2 billion economy via salaries, vendor payments, food aid, construction and other activities,” the International Crisis Group wrote in a report published a month before the war broke out:

If both UNRWA services and those jobs disappear, and along with them the purchasing power they bring, the impact would radiate throughout Gazan society. Many would lose their livelihoods, precipitating the collapse of small businesses and curtailing new construction. Refugees would be left without primary health care and their children without an education. These are just the most obvious effects.

The current situation is far more dire. Since October, large segments of Gaza’s population have been living in UNRWA schools, clinics, and other buildings, relying on the agency no longer just to make a living but for food and shelter to stay alive. The European Union recently said that it had not received concrete evidence from Israel to back its accusations against UNRWA staff, but the new US budget nonetheless defunds the agency into next year.

Meanwhile, on March 24 Lazzarini reported that Israeli authorities had informed the agency “they will no longer approve any UNRWA food convoys to the north.” In an interview with Al Jazeera, Sam Rose, the agency’s director of planning, stressed that the decision would have “dramatic” implications: “simply more people will die.” As if this were not enough, for the past three months Israeli protestors led by settlers from the West Bank, evidently unsatisfied by the devastation Israel has already wrought, have taken it upon themselves to block aid deliveries at the Kerem Shalom crossing. With each new development, one can only wonder what more Israel intends to do to annihilate Gaza’s population and render the region’s recovery impossible.