1.

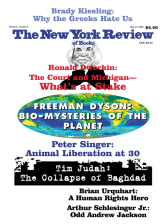

The phrase “Animal Liberation” appeared in the press for the first time on the April 5, 1973, cover of The New York Review of Books. Under that heading, I discussed Animals, Men and Morals, a collection of essays on our treatment of animals, which was edited by Stanley and Roslind Godlovitch and John Harris.1 The article began with these words:

We are familiar with Black Liberation, Gay Liberation, and a variety of other movements. With Women’s Liberation some thought we had come to the end of the road. Discrimination on the basis of sex, it has been said, is the last form of discrimination that is universally accepted and practiced without pretense, even in those liberal circles which have long prided themselves on their freedom from racial discrimination. But one should always be wary of talking of “the last remaining form of discrimination.”

In the text that followed, I urged that despite obvious differences between humans and nonhuman animals, we share with them a capacity to suffer, and this means that they, like us, have interests. If we ignore or discount their interests, simply on the grounds that they are not members of our species, the logic of our position is similar to that of the most blatant racists or sexists who think that those who belong to their race or sex have superior moral status, simply in virtue of their race or sex, and irrespective of other characteristics or qualities. Although most humans may be superior in reasoning or in other intellectual capacities to nonhuman animals, that is not enough to justify the line we draw between humans and animals. Some humans—infants and those with severe intellectual disabilities—have intellectual capacities inferior to some animals, but we would, rightly, be shocked by anyone who proposed that we inflict slow, painful deaths on these intellectually inferior humans in order to test the safety of household products. Nor, of course, would we tolerate confining them in small cages and then slaughtering them in order to eat them. The fact that we are prepared to do these things to nonhuman animals is therefore a sign of “speciesism”—a prejudice that survives because it is convenient for the dominant group—in this case not whites or males, but all humans.

That essay and the book that grew out of it, also published by The New York Review,2 are often credited with starting off what has become known as the “animal rights movement”—although the ethical position on which the movement rests needs no reference to rights. Hence the essay’s thirti-eth anniversary provides a convenient opportunity to take stock both of the current state of the debate over the moral status of animals and of how effective the movement has been in bringing about the practical changes it seeks in the way we treat animals.

2.

The most obvious difference between the current debate over the moral status of animals and that of thirty years ago is that in the early 1970s, to an extent barely credible today, scarcely anyone thought that the treatment of individual animals raised an ethical issue worth taking seriously. There were no animal rights or animal liberation organizations. Animal welfare was an issue for cat and dog lovers, best ignored by people with more important things to write about. (That’s why I wrote to the editors of The New York Review with the suggestion that they might review Animals, Men and Morals, whose publication the British press had greeted a year earlier with total silence.)

Today the situation is very different. Issues about our treatment of animals are often in the news. Animal rights organizations are active in all the industrialized nations. The US animal rights group called People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals has 750,000 members and supporters. A lively intellectual debate has sprung up. (The most comprehensive bibliography of writings on the moral status of animals lists only ninety-four works in the first 1970 years of the Christian era, and 240 works between 1970 and 1988, when the bibliography was completed.3 The tally now would probably be in the thousands.) Nor is this debate simply a Western phenomenon—leading works on animals and ethics have been translated into most of the world’s major languages, including Japanese, Chinese, and Korean.

To assess the debate, it helps to distinguish two questions. First, can speciesism itself—the idea that it is justifiable to give preference to beings simply on the grounds that they are members of the species Homo sapiens —be defended? And secondly, if speciesism cannot be defended, are there other characteristics about human beings that justify them in placing far greater moral significance on what happens to them than on what happens to nonhuman animals?

The view that species is in itself a reason for treating some beings as morally more significant than others is often assumed but rarely defended. Some who write as if they are defending speciesism are in fact defending an affirmative answer to the second question, arguing that there are morally relevant differences between human beings and other animals that entitle us to give more weight to the interests of humans.4 The only argument I’ve come across that looks like a defense of speciesism itself is the claim that just as parents have a special obligation to care for their own children in preference to the children of strangers, so we have a special obligation to other members of our species in preference to members of other species.5

Advertisement

Advocates of this position usually pass in silence over the obvious case that lies between the family and the species. Lewis Petrinovich, professor emeritus at the University of California, Riverside, and an authority on ornithology and evolution, says that our biology turns certain boundaries into moral imperatives—and then lists “children, kin, neighbors, and species.”6 If the argument works for both the narrower circle of family and friends and the wider sphere of the species, it should also work for the middle case: race. But an argument that supported our preferring the interests of members of our own race over those of members of other races would be less persuasive than one that allowed priority only for kin, neighbors, and members of our species. Conversely, if the argument doesn’t show race to be a morally relevant boundary, how can it show that species is?

The late Harvard philosopher Robert Nozick argued that we can’t infer much from the fact that we do not yet have a theory of the moral importance of species membership. “No one,” he wrote, “has spent much time trying to formulate” such a theory, “because the issue hasn’t seemed pressing.”7 But now that nearly twenty years have passed since Nozick wrote those words, and many people have, during those years, spent quite a lot of time trying to defend the importance of species membership, Nozick’s comment takes on a different weight. The continuing failure of philosophers to produce a plausible theory of the moral importance of species membership indicates, with increasing probability, that there can be no such thing.

That takes us to the second question. If species is not morally important in itself, is there something else that happens to coincide with the human species, on the basis of which we can justify the inferior consideration we give to nonhuman animals?

Peter Carruthers argues that it is the lack of a capacity to reciprocate. Ethics, he says, arises out of an agreement that if I do not harm you, you will not harm me. Since animals cannot take part in this social contract we have no direct duties to them.8 The difficulty with this approach to ethics is that it also means we have no direct duties to small children, or to future generations yet unborn. If we produce radioactive waste that will be deadly for thousands of years, is it unethical to put it into a container that will last 150 years and drop it into a convenient lake? If it is, ethics cannot be based on reciprocity.

Many other ways of marking the special moral significance of human beings have been suggested: the ability to reason, self-awareness, possession of a sense of justice, language, autonomy, and so on. But the problem with all of these allegedly distinguishing marks is, as noted above, that some humans are entirely lacking in these characteristics and few want to consign them to the same moral category as nonhuman animals.

This argument has become known by the tactless label of “the argument from marginal cases,” and has spawned an extensive literature of its own.9 The attempt by the English philosopher and conservative columnist Roger Scruton to respond to it in Animal Rights and Wrongs illustrates both the strengths and weaknesses of the argument. Scruton is aware that if we accept the prevailing moral rhetoric that asserts that all human beings have the same set of basic rights, irrespective of their intellectual level, the fact that some nonhuman animals are at least as rational, self-aware, and autonomous as some human beings looks like a firm basis for asserting that all animals have these basic rights. He points out, however, that this prevailing moral rhetoric is not in accord with our real attitudes, because we often regard “the killing of a human vegetable” as excusable. If human beings with profound intellectual disabilities do not have the same right to life as normal human beings, then there is no inconsistency in denying that right to nonhuman animals as well.

In referring to a “human vegetable,” however, Scruton makes things too easy for himself, for that expression suggests a being that is not even conscious, and thus has no interests at all that need to be protected. He might be less comfortable making his point with respect to a human being who has as much awareness and ability to learn as the foxes he wants to continue being permitted to hunt. In any case, the argument from marginal cases is not limited to the question of what beings we can justifiably kill. In addition to killing animals, we inflict suffering on them, in a wide variety of ways. So the defenders of common practices involving animals owe us an explanation for their willingness to make animals suffer when they would not be willing to do the same to humans with similar intellectual capacities. (Scruton, to his credit, is opposed to the close confinement of modern animal raising, saying that “a true morality of animal welfare ought to begin from the premise that this way of treating animals is wrong.”)

Advertisement

Scruton is in fact only half-willing to acknowledge that a “human vegetable” may be treated differently from other human beings. He muddies the waters by claiming that it is “part of human virtue to acknowledge human life as sacrosanct.” In addition, he argues that because in normal conditions human beings are members of a moral community protected by rights, even deeply serious abnormality does not cancel membership of this community. Thus even though humans with profound intellectual disability do not really have the same claims on us as normal humans, we would do well, Scruton says, to treat them as if they did. But is this defensible? Certainly if any sentient being, human or nonhuman, can feel pain or distress, or conversely can enjoy life, we ought to give the interests of that being the same consideration as we give to the similar interests of normal human beings with unimpaired capacities. To say, however, that species alone is both necessary and sufficient for being a member of our moral community, and for having the basic rights granted to all members of that community, requires further justification. We return to the core question: Should all and only human beings be protected by rights, when some nonhuman animals are superior in their intellectual capacities, and have richer emotional lives, than some human beings?

One well-known argument for an affirmative answer to this question asserts that unless we can draw a clear boundary around the moral community, we will find ourselves on a slippery slope.10 We may start by denying rights to Scruton’s “human vegetable,” that is, to those who can be shown to be irreversibly unconscious, but then we may gradually extend the category of those without rights to others, perhaps to the intellectually disabled, or to the demented, or just to those whose care is a burden on their family and the community, until in the end we have reached a situation that none of us would have accepted if we had known we were heading there when we denied the irreversibly unconscious a right to life. This is one of several arguments critically examined by the Italian animal activist Paola Cavalieri in The Animal Question: Why Nonhuman Animals Deserve Human Rights, a rare contribution to the English-language debate by a writer from continental Europe. Cavalieri points to the ease with which slave-owning societies were able to draw lines between humans with rights and humans without rights.

That slaves were human beings was acknowledged both in ancient Greece and in the slaveholding states of the US—Aristotle explicitly says that barbarians are human beings who exist to serve the good of the more rational Greeks,11 and Southern whites sought to save the souls of the Africans they enslaved by making them Christians. Yet the line between slaves and free people did not slip significantly, even when some barbarians and some Africans became free, or when slaves produced children of mixed race. So, Cavalieri suggests, there is no reason to doubt our ability to deny that some humans have rights, while keeping the rights of other humans as secure as ever. But she is certainly not advocating that we do this. Her concern is rather to undermine the argument for drawing the boundaries of the sphere of rights so as to include all and only humans.

Cavalieri also responds to the argument that all humans, including the irreversibly unconscious, are to be elevated above other animals because of the characteristics they “normally” possess, rather than those they actually have. This argument seems to appeal to a kind of unfairness in excluding those who “fortuitously” fail to have the required characteristics. Cavalieri replies that if the “fortuitousness” is merely statistical, it carries no moral relevance, and if it is intended to suggest that the lack of the required characteristics is not the fault of those with profound intellectual disability, then that is not a basis for separating such humans from nonhuman animals.

Cavalieri states her own position in terms of rights, and in particular the basic rights that constitute what, following Ronald Dworkin, she calls the “egalitarian plateau.” We want, Cavalieri insists, to secure a basic form of equality for all human beings, including the “non-paradigmatic” ones (her term for “marginal cases.”) If the egalitarian plateau is to have a defensible, nonarbitrary boundary that safeguards all humans from being pushed off the edge, we must select as a criterion for that boundary a standard that allows a large number of nonhuman animals inside the boundary as well. Hence we must allow onto the egalitarian plateau beings whose intellect and emotions are at a level that is shared by, at least, all birds and mammals.

Cavalieri does not argue that the rights of birds and mammals can be derived from self-evidently true moral premises. Her starting point, rather, is our prevailing belief in human rights. She seeks to show that all who accept this belief must also accept that similar rights apply to other animals. Following Dworkin, she sees human rights as part of the basic political framework of a decent society. They set limits to what the state may justifiably do to others. In particular, institutions like slavery or other invidious forms of racial discrimination that are based on violating the human rights of some of those over whom the state rules are, for that reason alone, illegitimate. Our acceptance of the idea of human rights therefore requires the abolition of all practices that routinely overlook the basic interests of rights-holders. Hence, if Cavalieri’s argument is sound, our belief in rights commits us to an extension of rights beyond humans, and that in turn requires us to abolish all practices, like factory farming and the use of animals as subjects of painful and lethal research, that routinely overlook the basic interests of nonhuman rights-holders.

On the other hand, the rights for which Cavalieri argues are not supposed to resolve every situation in which there is a conflict of interests or of rights. Her notion of rights as part of the basic political framework of a decent society is compatible with specific restrictions of rights, as occurred for example when “Typhoid Mary” was compulsorily quarantined because she carried a lethal disease. A government may be entitled to restrict the movements of humans or animals who are a danger to the public, but it must still show them the concern and respect due to them as possessors of basic rights.12

My own opposition to speciesism is based, as I have already mentioned, not on rights, but on the thought that a difference of species is not an ethically defensible ground for giving less consideration to the interests of a sentient being than we give to similar interests of a member of our own species. David DeGrazia skillfully defends equal consideration for all sentient beings in Taking Animals Seriously. Such a position need not rely on prior acceptance of our current view of human rights—a view that, though widespread, can be rejected, especially once its implications in regard to animals are drawn out as Cavalieri draws them out. While the principle of equal consideration of interests is therefore more solidly based than Cavalieri’s argument, however, it must face the difficulties that follow from the fact that interests, not rights, are now the focus of attention. That requires us to estimate what the interests are in an endless variety of different circumstances.

To take one case of particular ethical significance: the interest a being has in continued life—and hence, on the interests view, the wrongness of taking that being’s life—will depend in part on whether the being is aware of itself as existing over time, and is capable of forming future-directed desires that give it a particular kind of interest in continuing to live. To that extent Roger Scruton is right about our attitudes to the deaths of members of our own species who lack these characteristics. We see it as less of a tragedy than the death of a being who is future-oriented, and whose desires to do things in the medium- and long-term future will therefore be thwarted if he or she dies.13 But this is not a defense of speciesism, for it implies that killing a self-aware being like a chimpanzee causes a greater loss to the being killed than does killing a human being with an intellectual disability so severe as to preclude the capacity to form desires for the future.

We then need to ask what other beings may have this kind of interest in living into the future. DeGrazia combines philosophical insights and scientific research to help us answer such questions about specific species of animals, but there is often room for doubt, and the calculations required for applying the principle of equal consideration of interests can only be rough approximations, if they can be done at all. Perhaps, though, that is just the nature of our ethical situation, and rights-based views avoid such calculations at the cost of leaving out something relevant to what we ought to do.

The most recent addition to the literature of the animal movement has come from a surprising quarter, one deeply hostile to any discussion of the possibility of justifying the killing of human beings, no matter how severely disabled they may be. In Dominion: The Power of Man, the Suffering of Animals, and the Call to Mercy Matthew Scully, a conservative Christian, past literary editor of National Review and now speechwriter to President George W. Bush, has written an eloquent polemic against human abuse of animals, culminating with a devastating description of factory farming.

Since the animal movement has, for the past thirty years, generally been associated with the left, it is curious now to see Scully make a case for many of the same goals within the perspective of the Christian right, replete with references to God, interpretation of the scripture, and attacks on “moral relativism, self-centered materialism, license passing itself off as freedom, and the culture of death”14—but this time aimed at condemning not vic-timless crimes like homosexuality or physician-assisted suicide, but the needless suffering inflicted by factory farming and the modern slaughterhouse. Scully calls on all of us to show mercy toward animals and abandon ways of treating them that fail to respect their nature as animals. The result is a work that, although not philosophically rigorous, has had a remarkable amount of sympathetic publicity in the conservative press, which usually sneers at animal advocates.

3.

The history of the modern animal movement makes a nice counterexample to skepticism about the impact of moral argument on real life.15 As James Jasper and Dorothy Nelkin observed in The Animal Rights Crusade: The Growth of a Moral Protest, “Philosophers served as midwives of the animal rights movement in the late 1970s.”16 The first successful protest against animal experiments in the United States was the 1976–1977 campaign against experiments conducted at the American Museum of Natural History on the sexual behavior of mutilated cats. Henry Spira, who conceived and ran the campaign, had a background of working in the union and civil rights movements, and had not considered, until he read the 1973 New York Review article, that animals are also worth the attention of those concerned about the exploitation of the weak. Spira went on to take on larger targets, such as the testing of cosmetics on animals. His technique was to target a prominent corporation that used animals—in the cosmetics campaign, he started with Revlon—and ask them to take reasonable steps to find alternatives to the use of animals. Always willing to engage in dialogue, and never one to paint the abusers of animals as evil sadists, he was remarkably successful in stimulating interest in developing ways of testing products without using animals, or with using fewer animals in less painful ways.17

Partly as a result of his work, there has also been a sizable drop in the number of animals used in research. In Britain official statistics show that roughly half as many animals are now experimented upon as were used in 1970. Estimates for the United States—where no official statistics are kept—suggest a similar story. From the standpoint of a nonspeciesist ethic there is still a long way to go for animals used in research, but the changes the animal movement has brought about mean that every year millions fewer animals are forced to undergo painful procedures and slow deaths.

The animal movement has had other successes too. Despite “fur is back” claims by the industry, fur sales have still not recovered to their level in the 1980s, when the animal movement began to target it. Since 1973, while the number of dogs and cats owned has nearly doubled, the number of stray and unwanted animals killed in pounds and shelters has been cut by more than half.18

These modest gains are dwarfed, however, by the huge increase in animals kept confined, some so tightly that they are unable to stretch their limbs or walk even a step or two, on America’s factory farms. This is by far the greatest source of human-inflicted suffering on animals, simply because the numbers are so great. Animals used in experiments are numbered in the tens of millions annually, but last year ten billion birds and mammals were raised and killed for food in the United States alone. The increase over the previous year is, at around 400 million animals, more than the total number of animals killed in the US by pounds and shelters, for research, and for fur combined. The overwhelming majority of these factory-reared animals now live their lives entirely indoors, never knowing fresh air, sunshine, or grass until they are trucked away to be slaughtered.

Against the confinement and slaughter of farm animals in America, the animal movement has, until quite recently, been impotent. Gail Eisnitz’s 1997 book Slaughterhouse contains shocking, well-authenticated accounts of animals in major American slaughterhouses being skinned and dismembered while still conscious.19 If such incidents had been documented in Britain they would have led to major news stories and the national government would have been forced to do something about it. Here the book passed virtually unnoticed outside the animal movement.

The situation is very different in Europe. Americans have often looked down on some European nations, especially the Mediterranean countries, for tolerating cruelty to animals. Now the accusing glance goes in the opposite direction. Even in Spain, with its culture of bull-fighting, most animals are better cared for than in America. By 2012, European egg producers will be required to give their hens access to a perch and a nesting box to lay their eggs in, and to allow at least 750 square centimeters, or 120 square inches, per bird—dramatic changes that will transform the living conditions of more than two hundred million hens. United States egg producers haven’t even started thinking about perches or nesting boxes, and typically give their fully grown hens just forty-eight square inches, or about half the area of a sheet of 81/2-x-11-inch letter paper per bird.20

In the US veal calves are deliberately kept anemic, deprived of straw for bedding, and confined in individual crates so narrow that they cannot even turn around. That system of keeping calves has been illegal in Britain for many years, and will become illegal throughout the European Union by 2007. Keeping pregnant sows in individual crates for their entire pregnancy, also the standard American practice, was banned in Britain in 1998, and is being phased out in Europe. These changes have wide support throughout the European Union, and the backing of leading European experts on the welfare of farm animals. They are a vindication of much that animal advocates have been saying for the past thirty years.

Are Americans simply less concerned with animal suffering than their European counterparts? Perhaps, but in Political Animals: Animal Protection Policies in Britain and the United States, Robert Garner explores several other possible explanations for the widening gap in animal welfare standards between the two nations.21 By comparison with Britain, the US political process is more corrupt. Elections are many times more costly—the entire 2001 British general election cost less than John Corzine spent to win a single Senate seat in 2000. With money playing a greater role, American candidates are more beholden to their donors. Moreover, fund raising in Europe is largely done by the political parties, not by individual candidates, which makes it more open to public scrutiny and more likely to produce an electoral backlash for the entire party if it is seen to be in the pocket of a particular industry. These differences allow the agribusiness industry far greater control over Congress than it can hope to have over the political processes in Europe.

Consistent with that explanation, the most successful American campaigns—like Spira’s campaign against the use of animals to test cosmetics—have concentrated on corporations rather than on the legislature or the government. Recently a ray of hope has come from an unlikely vehicle for change. After protracted discussions with animal advocates, started by Henry Spira before his death and then taken up by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, McDonald’s agreed to set and enforce higher standards for the slaughterhouses that supply it with meat, and then announced that it would require its egg suppliers to provide each hen with a minimum of seventy-two square inches of living space—a 50 percent improvement for most American hens, but still only enough to bring these producers up to a level that is already on its way out in Europe. Burger King and Wendy’s followed suit. These steps were the first hopeful signs for American farm animals since the modern animal movement began.

An even greater triumph was achieved last November by using another route around the legislative roadblock: the citizen-initiated referendum. With support from a number of national animal organizations, a group of animal activists in Florida succeeded in gathering 690,000 signatures to put on the ballot a proposal to change the constitution of Florida so as to ban the keeping of pregnant sows in crates so narrow that they cannot even turn around. Changing the constitution is the only way citizens can get a direct vote on a measure in Florida. Opponents of the measure, obviously unwilling to argue that pigs don’t need to be able to turn around or walk, instead tried to persuade Florida voters that the confinement of pigs was not an appropriate subject for the state constitution. But by a margin of 55 to 45 percent, voters said no to sow crates, thus making Florida the first jurisdiction in the United States to ban a major form of farm-animal confinement. Though Florida has only a small number of intensive piggeries, the vote supports the idea that it is not hard hearts or lack of sympathy for animals but a failure of democracy that causes America to lag so far behind Europe in abolishing the worst features of factory farming.

4.

My original article in The New York Review ended with a paragraph that saw the challenge of the animal movement as a test of human nature:

Can a purely moral demand of this kind succeed? The odds are certainly against it. The book [Animals, Men and Morals] holds out no inducements. It does not tell us that we will become healthier, or enjoy life more, if we cease exploiting animals. Animal Liberation will require greater altruism on the part of mankind than any other liberation movement, since animals are incapable of demanding it for themselves, or of protesting against their exploitation by votes, demonstrations, or bombs. Is man capable of such genuine altruism? Who knows? If this book does have a significant effect, however, it will be a vindication of all those who have believed that man has within himself the potential for more than cruelty and selfishness.

So how have we done? Both the optimists and the cynics about human nature could see the results as confirming their views. Significant changes have occurred, in animal testing and other forms of animal abuse. In Europe, entire industries are being transformed because of the concern of the public for the welfare of farm animals. Perhaps most encouraging for the optimists is the fact that millions of activists have freely given up their time and money to support the animal movement, many of them changing their diet and lifestyle to avoid supporting the abuse of animals. Vegetarianism and even veganism (avoiding all animal products) are far more widespread in North America and Europe than they were thirty years ago, and although it is difficult to know how much of this relates to concern for animals, undoubtedly some of it does.

On the other hand, despite the generally favorable course of the philosophical debate about the moral status of animals, popular views on that topic are still very far from adopting the basic idea that the interests of all beings should be given equal consideration irrespective of their species. Most people still eat meat, and buy what is cheapest, oblivious to the suffering of the animal from which the meat comes. The number of animals being consumed is much greater today than it was thirty years ago, and increasing prosperity in East Asia is creating a demand for meat that threatens to boost that number far higher still. Meanwhile the rules of the World Trade Organization threaten advances in animal welfare by making it doubtful that Europe will be able to keep out imports from countries with lower standards. In short, the outcome so far indicates that as a species we are capable of altruistic concern for other beings; but imperfect information, powerful interests, and a desire not to know disturbing facts have limited the gains made by the animal movement.

This Issue

May 15, 2003

-

1

Taplinger, 1972. ↩

-

2

Peter Singer, Animal Liberation (New York Review/Random House, 1975; revised edition, New York Review/ Random House, 1990; reissued with a new preface, Ecco, 2001). ↩

-

3

Charles Magel, Keyguide to Information Sources in Animal Rights (McFarland, 1989). ↩

-

4

See, for example, Carl Cohen, “The Case for the Use of Animals in Biomedical Research,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 315 (1986), pp. 865–870; and Michael Leahy, Against Liberation: Putting Animals in Perspective (London: Routledge, 1991). ↩

-

5

See Mary Midgley, Animals and Why They Matter (University of Georgia Press, 1984); Jeffrey Gray, “On the Morality of Speciesism,” Psychologist, Vol. 4, No. 5 (May 1991), pp. 196–198, and “On Speciesism and Racism: Reply to Singer and Ryder,” Psychologist, Vol. 4, No. 5 (May 1991), pp. 202–203; and Lewis Petrinovich, Darwinian Dominion: Animal Welfare and Human Interests (MIT Press, 1999). ↩

-

6

Petrinovich, Darwinian Dominion, p. 29. ↩

-

7

Robert Nozick, “About Mammals and People,” The New York Times Book Review, November 27, 1983, p. 11; I draw here on Richard I. Arneson, “What, If Anything, Renders All Humans Morally Equal?” in Singer and His Critics, edited by Dale Jamieson (Blackwell, 1999), p. 123. ↩

-

8

Peter Carruthers, The Animals Issue: Moral Theory in Practice (Cambridge University Press, 1992). ↩

-

9

Daniel Dombrowski, Babies and Beasts: The Argument from Marginal Cases (University of Illinois Press, 1997). ↩

-

10

See, for example, Peter Carruthers, The Animals Issue. ↩

-

11

Aristotle, Politics (London: J.M. Dent and Sons, 1916), p. 16. ↩

-

12

As Dworkin himself argued in regard to the detention of suspected terrorists; see “The Threat to Patriotism,” The New York Review, February 28, 2002. ↩

-

13

See my Practical Ethics (Cambridge University Press, 1993), especially Chapter 4. ↩

-

14

Quoted from Kathryn Jean Lopez, “Exploring ‘Dominion’: Matthew Scully on Animals,” National Review Online, December 3, 2002. ↩

-

15

See, for example, See Richard A. Posner, The Problematics of Moral and Legal Theory (Belnap Press/Harvard University Press, 1999). ↩

-

16

Free Press, 1992, p. 90. ↩

-

17

See Peter Singer, Ethics into Action: Henry Spira and the Animal Rights Movement (Rowman and Littlefield, 1998). ↩

-

18

The State of the Animals 2001, edited by Deborah Salem and Andrew Rowan (Humane Society Press, 2001). ↩

-

19

Prometheus, 1997. ↩

-

20

See Karen Davis, Prisoned Chickens, Poisoned Eggs: An Inside Look at the Modern Poultry Industry (Book Publishing Company, 1996). ↩

-

21

St. Martin’s, 1998. ↩