This statement appeared in the first issue of The New York Review, February 1, 1963.

To the Reader: The New York Review of Books presents reviews of some of the more interesting and important books published this winter. It does not, however, seek merely to fill the gap created by the printers’ strike in New York City but to take the opportunity which the strike has presented to publish the sort of literary journal which the editors and contributors feel is needed in America. This issue of The New York Review does not pretend to cover all the books of the season or even all the important ones. Neither time nor space, however, have been spent on books which are trivial in their intentions or venal in their effects, except occasionally to reduce a temporarily inflated reputation or to call attention to a fraud. The contributors have supplied their reviews to this issue on short notice and without the expectation of payment: the editors have volunteered their time and, since the project was undertaken entirely without capital, the publishers, through the purchase of advertising, have made it possible to pay the printer. The hope of the editors is to suggest, however imperfectly, some of the qualities which a responsible literary journal should have and to discover whether there is, in America, not only the need for such a review but the demand for one. Readers are invited to submit their comments to The New York Review of Books, 33 West 67th Street, New York City.

—The Editors

15 West 67th Street

New York, NY

January 23, [1963]

Dearest Elizabeth:

We’ve been in a great flurry lately. Lizzie [his wife, Elizabeth Hardwick] is on the board of a new book review about to be set floating during the lull of the newspaper strike here that has temporarily put the New York Times book section out of existence. Meetings, arguments, telephone calls, and now at the end of two weeks, a fairly dazzling first number has been promised and will come out in the middle of February. One of my side-line duties was to phone Randall [Jarrell], who said he promised himself never again to write anything he could use in a book of essays. There was nothing he wanted to review. Then he paused and said there was one book, yours. He has been following all your new poems in the New Yorker, and is choosing a good many for a new anthology.

I pass this on to cheer you and perhaps prod you. The wolf with its head on its paws lies looking at the desolate yellow wastes of our present civilization, ready when your book comes to howl its welcome. This makes a difference. I remember my second book seemed lost in the dust of carping and the mildest praise, when Randall wrote a long piece violently liking and disliking. In a preface to Emily Dickinson, John Brinnin asks if she isn’t the greatest woman poet, brushes away the past, and then says only Marianne Moore and Elizabeth Bishop (of the English poets of this century) reach her level.

I don’t suppose you need praise, but I find there are sinking times when everything I do looks about like what dozens of others are doing, or worse. It’s pleasant to have an art that can never make money or much sensation; then in dry times it hardly seems to exist. You have more to offer, I think, than anyone writing poetry in English. On, Dear, with those painful, very large unfinished poems!

I am at the end of something. Up till now I’ve felt I was all blue spots and blotches inside, more than I could bear really, if I looked at myself, and of course I wanted to do nothing else. So day after day, I wrote, sometimes too absorbed to even stop for lunch and often sitting with my family in a stupor, mulling over a phrase or a set of lines for almost hours, hypnotized, under a spell, often a bad spell. Now out of this, I have seven poems and seven translations, just about a book when added to what I had before. Now I say to myself, “Out of jail!” I look back on the last months with disgust and gratitude[.] Disgust because they seem so monstrous, gratitude, because I have lived through the unintelligible, have written against collapse and come out more or less healed. Oh dear, have you ever felt like a man in an unreal book?

I begin my Harvard teaching next week, and have been boning up on the standard old Americans, Emerson, Longfellow, Bryant etc. They are much farther away than they were when I was in school and college. Then they were almost something one shouldn’t read much of lest they led astray. Now the times have brought them back maybe,—hardly imitated still, they are like our own kind of revolt and competence. The beats have blown away, the professionals have returned. Sometimes they flash—Emerson is a funny case of the poet who was all flash in theory and desire and even gifts, and somehow his equipment and instincts wouldn’t let him. Then a lovely moment would come.[…]

Love,

Cal

15 West 67th Street

New York, NY

March 10, 1963

Dearest Elizabeth:

I think of you daily and feel anxious lest we lose our old backward and forward flow that always seems to open me up and bring color and peace.

Things are gayer now, but we indeed live in the current. Each Monday I fly to Boston, each Wednesday or Thursday morning I fly back. This gives me two short weeks, each with its own air and pace, instead of my old all of one cloth New York weeks. The teaching is enjoyable, not too much work really, unlocking in a mild way, except that of course one sees too many people and talks too much about poetry to too many embryonic poets. Here we are in the hectic whirl of putting out the new book review. I’m very much a bystander and admirer. But Lizzie is furiously engaged and in a way making inspired use of her abilities—for God knows we need a review that at least believes in standards and can intuit excellence. The bad side is a rush around us of the excoriated and excoriating—nerves and people. We live in the fire and burnt-outness of some political or religious movement.

I want to send you a few books or two at least. Hannah [Arendt]’s book on revolutions is somewhat diffuse and theoretical but is full of things that give me pause and I think we would both feel. She approves of the American Revolution but finds it somehow somewhat abstract and inspired no serious thought after Jefferson and the founders. The French Revolution however which she thinks doomed to violence and tyranny began with pity for the miserable, set up standards of violence and unlimited desire and has inspired generations of thinkers. She is wonderful on how sentiments of compassion get changed into blood power-lust and dictatorship. This is a very garbled way of expressing her dense thought, but she brings home to me frighteningly how certain redcapped liberal feelings can go with a sinister acceptance of the terrible.

The other book is quite different, a magical little essay on Herbert by Eliot.[…]

We are terribly interested in having you write a Brazilian letter for the Book Review—in your wonderful letter style and about anything that you want.

Love to you and Lota,

Cal

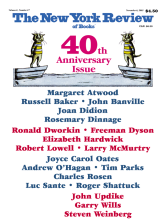

This Issue

November 6, 2003