On February 5, 1916, Hugo Ball, a German avant-garde theater director, and Emmy Hennings, his mistress and a nightclub singer, opened for the first time the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich where they presented exhibitions of contemporary art and performances of experimental music, poetry, and dance. The cabaret had a small stage, room for forty to fifty people in the audience, and was located in a seedy neighborhood of bars, variety shows, and cheap hotels in an otherwise respectable city in which many expatriate artists, writers, journalists, actors, intellectuals, and professional revolutionaries were then living, as well as international war profiteers and spies. Lenin rented rooms on the same narrow alley. Joyce worked on Ulysses in a neighborhood not very far away.

Dada did not yet exist as a movement, nor did it have a name. What started as a series of evenings where poems of modern German and French poets were recited, art songs performed, and compositions by Franz Liszt, Alexander Scriabin, and Claude Debussy played on the café’s piano changed over the next few weeks into something quite different under the influence of new arrivals on the scene. They were the poet Richard Huelsenbeck, whom Ball had known in Berlin, the Alsatian-born artist Hans Arp, and the twenty-year-old Romanian poet Tristan Tzara and his not-much-older compatriot, the painter Marcel Janco. What brought them together was their hatred of the war and their belief that both art and politics needed a revolutionary change.

Already while living in Berlin in 1915, Ball and Hennings had organized a series of antiwar literary evenings with the intention, they said, to provoke, perturb, bewilder, tease, tickle to death, and confuse the audience. In Zurich, Janco made cardboard masks reminiscent of the ones used in African rituals and Japanese theater, but also strikingly original. As Ball wrote in his journal, “The masks simply demanded that their wearers start to move in a tragic-absurd dance.”1 Patrons of the cabaret who came expecting to hear selections from the works of Voltaire and Turgenev or another balalaika orchestra were subjected instead to skits enacted by masked figures dressed in colorful costumes made from cardboard and poster paint who accompanied themselves with drums, pot covers, and frying pans as they recited poems that sounded like this:

Gadji beri bimba

Glandridi lauli lonni cadori

Gadjama bim beri glassala

Glandridi glassala tuffm Izimbrabim

Blassa galassasa tuffm Izimbrabim.2

The noise from the stage was deafening. There was bedlam in the audience too. The performers behaved like new recruits simulating mental illness before a medical commission. In less than a month the cabaret, which at first had welcomed all modern tendencies in the arts and hoped to entertain and educate the customer, had turned into a theater of the absurd. That was the intention. “What we are celebrating,” Ball wrote in his diary, “is both buffoonery and a requiem mass.”3 The scandal spread.Lenin, who played chess with Tzara, wanted to know what Dada was all about.

There has never been an easy answer. As late as 1920, Marcel Duchamp said he didn’t know what Dada was. The accounts of the original participants in Zurich are conflicting; there is even uncertainty about where the name came from. The most plausible version is that Ball and Huelsenbeck found the French word for “hobbyhorse” accidentally in a French–German dictionary while looking for something else. Another possibility is that it came from the name of a popular hair-strengthening tonic. Whatever its origin, the word, which in several Slavic languages sounds like an emphatic declaration of agreement (“yes, yes”), quickly became as popular as a brand name: a one-word manifesto guaranteed either to amuse or to irritate. Hans Arp tells how he and his friends used to make rounds of the bars, opening the door of each and saying in a loud, clear voice: “Long live Dada!” The patrons would open their mouths in amazement, dropping their forks and their sausages.

The attitude toward the arts that the Zurich Dada brought to light long precedes the movement. “Without knowing one another we worked towards the same goal,” Hans Arp later said.4 He found it sickening to feed art eternally with still lifes, landscapes, and nudes. All forms of imitation, the Italian Futurists had already announced, must be despised; all forms of originality glorified. The idea was to make something no one had ever seen or experienced before. The activities in Zurich gave a name to a loose confederation of artists and poets in New York, Berlin, Hannover, Cologne and Paris who exchanged letters and circulated little magazines and reproductions of their work without ever bothering to iron out their disagreements on aesthetic issues. They no longer believed in trying to understand things from a single point of view. Though they all pretty much did what they pleased, they shared an interest in abstraction, collage, photo- montage, and using chance as a tool. Even more important than any particular technique was their belief that the traditional division between art and non-art ought to be abolished. What they sought was the secret of making masterpieces while repudiating art.

Advertisement

The beginnings of Dada do not lie in art but in disgust, one of its leaders said. This was precisely the attitude of the Italian Futurists who just a few years earlier had demanded that we do away with museums, libraries, and other cultural landmarks for the sake of the Future. However, the war of 1914 divided the sympathies not only of intellectuals of various European countries, but of their avant-garde movements as well. “We will glorify war—the only true hygiene of the world—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of anarchist, the beautiful Ideas which kill, and the scorn of woman,” the Futurist Marinetti wrote.5 Quite the reverse, the poets and artists who were to call themselves Dadaists were pacifists and internationalists. Most of them were draft-dodgers on the run from military authorities in their respective countries. Their revulsion at the butchery of the Great War, in which about ten million men died, over twenty million were wounded, and several hundred thousand lost limbs and sight, had a lot to do with what Dada was to become.

Once the movement was launched, there were manifestos, of course, attempting to explain Dada to the uninitiated. The most famous early ones are by Tristan Tzara, Hugo Ball, and Richard Huelsenbeck. Their main purpose was not so much to enlighten but to outrage the public and create a scandal. Tzara wrote:

Every product of disgust capable of becoming a negation of the family is Dada; a protest with the fists of its whole being engaged in destructive action: Dada; knowledge of all the means rejected up until now by the shamefaced sex of comfortable compromise and good manners: Dada; abolition of logic, which is the dance of those impotent to create: Dada; of every social hierarchy and equation set up for the sake of values by our valets: Dada; every object, all objects, sentiments, obscurities, apparitions and the precise clash of parallel lines are weapons for the fight: Dada; abolition of memory: Dada; abolition of archaeology: Dada: abolition of prophets: Dada; abolition of the future: Dada; absolute and unquestionable faith in every god that is the immediate product of spontaneity: Dada; elegant and unprejudiced leap from a harmony to the other sphere: trajectory of a word tossed like a screeching phonograph record: to respect all individuals in their folly of the moment: whether it be serious, fearful, timid, ardent, vigorous, determined, enthusiastic; to divest one’s church of every useless cumbersome accessory; to spit out disagreeable or amorous ideas like a luminous waterfall, or coddle them—with the extreme satisfaction that it doesn’t matter in the least—with the same intensity in the thicket of one’s soul—pure of insects for blood well-born, and gilded with bodies of archangels. Freedom: Dada Dada Dada, a roaring of tense colors, and interlacing of opposites and of all contradictions, grotesques, inconsistencies: LIFE6

While Tzara’s manifesto conveyed the aggressive, polemical side of Dada, it didn’t really reflect the thinking of its more thoughtful members. Tzara had a genius for publicity, but he was no philosopher. Besides, the artists who came to be associated with the movement had no desire to follow a party line set down by any self-appointed leader. Oddly, there was always more agreement among Dada poets. “The elements of poetry are letters, syllables, words, sentences,” Kurt Schwitters wrote.7 Poetry, he insisted, arises from the playing off of these elements against one another. He also confessed to preferring nonsense to sense because it had always been neglected in the making of art. Tzara explained in a 1920 manifesto how such poems were to be made:

Take a newspaper.

Take a pair of scissors.

Choose an article as long as you are planning to make your poem.

Cut out the article.

Then cut out each of the words that make up this article and put them in a bag.

Shake it gently.

Then take out the scraps one after the other in the order in which they left the bag.

Copy conscientiously.

The poem will be like you.

And here you are a writer, infinitely original and endowed with a sensibility that is charming though beyond the understanding of the vulgar.8

This is the sort of thing the patrons of Cabaret Voltaire heard. One night Tzara, Janko, and Huelsenbeck took the stage to deliver what they called a “simultaneous poem” made up of separate texts spoken in French, German, and English at the same time. One of the participants compared it to the sound of the Balkan Express crossing a bridge and of a pig squealing in a butcher’s cellar. This was followed the same evening by the presentation of two chants nègres, bursts of nonsense language meant to evoke the rhythms of African songs. Ball even invented a “poem without words,” which consisted entirely of abstract sounds (such as the line “Gadji beri bimba” quoted above). The subject of such poems, Ball said, was the human voice standing for the individual soul as it battles against the noise of the world. As performance art, such poetry can be spellbinding. It was an attempt to strip poetic language of meaning, imagery, and even lyricism. Luckily, they were not wholly successful. Dada did not produce great literature, though there are many poems by Tzara, Arp, and Schwitters that are great fun to read.

Advertisement

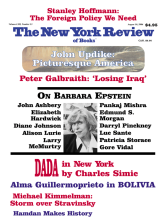

That’s not how the artists did it. What one encounters at the current Dada exhibition at MoMA is a proliferation of mutually exclusive styles. The show is the first major museum survey in the United States that deals exclusively with the Dada movement. That was news to me since the work of Marcel Duchamp, Hans Arp, Max Ernst, Man Ray, Kurt Schwitters, Francis Picabia, and George Grosz has long been familiar to museum visitors in this country. What may be less known is how brief their connection to the movement was. Dada lasted roughly from 1916 to 1924, but the actual involvement of many of its participants was not even that long. One of the surprises of the MoMA show is that most of the paintings, sculptures, photographs, collages, photomontages, prints, assemblages, and films were done in such a short time. (Of course the readymades—commonplace manufactured objects—simply had to be put on display.) When one recalls the huge influence Dada has had and continues to have among avant-garde artists and poets, one is likely to leave the museum convinced that there hasn’t been a single new idea in the last eighty years.

There are nearly 450 works by fifty artists in the MoMA show. The large catalog to the exhibition, which originated at the Pompidou Center in Paris and traveled to the National Gallery in Washington before New York, comes with an introduction, six scholarly essays, hundreds of color and black-and-white reproductions, biographies of the individual artists, and a detailed chronology, making it one of the most comprehensive histories of the movement ever published. It’s worth having because a number of notable works reproduced in it are not in the show. The exhibition is organized around six interconnected spaces, each devoted to one of the cities in which Dada flourished. There should have been more room in New York, as there was at the National Gallery. Too many art objects are on display in too small a space and the boundaries between Dada cities are not always clear. Nevertheless, seeing the show is an exhilarating experience. Only those who never had the slightest temptation to break any rules could possibly take fright here.

In the space devoted to Dada in Zurich, one finds Janco’s astonishing masks, Arp’s collages and painted wood reliefs, abstract needlepoint by the Swiss artist Sophie Taeuber, sculptures made of turned wood and marionettes for a puppet theater play, Hans Richter’s expressionist-looking portraits, Picabia’s tongue-in-cheek technical drawings, and Christian Schad’s abstract photographs. Taeuber, who designed textiles and taught at the Zurich School of Applied Arts, brought the tradition of abstraction from decorative arts over into sculpture and painting. Her pieces are among the greatest delights of this exhibition. They have about them the authority and elegance of folk art. Arp also rejected mimesis. He tore paper into squares of various sizes which he then dropped onto a sheet of paper and pasted into place where they fell. He did the same with his abstract wood reliefs, generating forms from automatic drawings which he then had a carpenter cut into shapes. It’s hard to believe that Arp let the pieces of paper remain where they fell, that he was never tempted to shift them a bit because they looked better that way, or that he didn’t choose some sheets of paper and discard others. Whatever he did, he succeeded in both making his collages formally coherent and giving the appearance of randomness.

The beginnings of the Dada movement in Berlin are tied to the return of Richard Huelsenbeck from Zurich in early 1917. He spread the news of what had happened there during the preceding year and soon joined the artists George Grosz, John Heartfield, Wieland Herzfelde, and Franz Jung in founding Club Dada, which was soon to include Johannes Baader, Raoul Hausmann, and Hannah Höch among its members. On April 12, 1918, they staged an evening of lectures, poetry readings, and performances. “The threat of violence hung in the air,” one newspaper wrote. While Hausmann was reading a pugnacious manifesto, the manager of the gallery turned out the lights. This was the beginning of Berlin activities which culminated two years later in the First International Dada Fair, where nearly two hundred works of art were exhibited.

What set apart the Berlin Dadaists from the ones in Zurich was their clear political message. A number of them were members of the recently founded German Communist Party and were used to passing flyers and selling seditious broadsheets in the street. Some of the Dadaists were jailed; Dada publications were banned and their publishers sued for blasphemy and for having slandered the German military. It is unthinkable that such savage political satire would be published in the United States today. What caused it to be even more effective than traditional caricature was the use of photomontage, which made it possible to paste the face of the Kaiser on a bathing beauty or on a mechanical puppet. Other figures of the German political and military elite were similarly dissected and reassembled using body parts cut out of news photos, fashion plates, and commercial advertisements.

Who invented photomontage? Again, there are conflicting recollections. This is Hausmann’s:

In nearly every house there was to be found hanging on the wall a color lithograph depicting an infantryman in front of military barracks. In order to render this memento of the military service of a male member of the family more personal, a portrait photograph of the owner of the martial image had been glued in place of the head in the lithograph. It was like a thunderbolt: one could—I saw it instantaneously—make pictures, assembled entirely from cut-up photographs. Back in Berlin that September, I began to realize this new vision, and I made use of photographs from the press and the cinema.

Hannah Höch, who was with Hausmann when the discovery was made, confirms his story. However, the idea may also have come from the practice during the war of pasting subversive photographs and advertisements from newspapers on the postcards sent to soldiers at the front. “Collisions are necessary: things are still not cruel enough,” Huelsenbeck said.9 Germany was on the verge of civil war with strikes, uprisings of workers, street fighting, and a catastrophic economic situation and the art reflects the mood of the times. “Blood is the best sauce,” says a caption to one of George Grosz’s lithographs depicting two men dining elegantly while soldiers bayonet each other outside the restaurant terrace. Politically charged drawings, collages, photomontages, and paintings by George Grosz, Raoul Hausmann, John Heartfield, Johannes Baader, Hannah Höch, and the wonderfully irreverent Georg Scholz, Otto Dix, and Rudolf Schlichter make the Berlin part of the exhibition especially memorable.

Hannover was not a Dada center in the way that Zurich and Berlin were. It was really a one-man enterprise. Kurt Schwitters, who was to become one of the major and most original figures in modern art, was an expressionist painter until 1917. He then adopted collage as his preferred medium, eventually extending its principles to sculpture, architecture, graphic design, music, poetry, and criticism. He gave his art the general name “Merz,” which meant openness to any and all materials in making art. In her fine essay on Schwitters in the catalog, Dorothea Dietrich cites his manifesto:

Merzbilder (Merz pictures) are abstract works of art. The word Merz denotes essentially the combination of all conceivable materials for artistic purposes, and technically the principle of equal evaluation of the individual materials. Merzmalerei [Merz painting] makes use not only of paint and canvas, brush and palette, but of all materials perceptible to the eye and of all required implements. Moreover, it is unimportant whether the material used was already formed for some purpose or other. A perambulator wheel, wire-netting, string and cotton wool are factors having equal rights with paint. The artist creates through choice, distribution and dematerialization of the materials.

Schwitters wanted to efface the boundaries between all arts. He built his collages and assemblages of materials using anything he could get his hands on: newspapers, labels, leaflets, pieces of wood, and other trash, which he then pasted in layers to a wooden board or canvas, the new layers partly obscuring what was underneath, thickening the texture and transforming the whole into an object never seen before. Dorothea Dietrich points out the tension between the visual and textual in Schwitters’s collages. The eyes shift between attempting to decipher the minutiae and trying to take in the whole. This, of course, was even truer of the photomontages Berlin Dadaists produced, where all the fun for the viewer is in the details. Even more than Hannah Höch or Raoul Hausmann, Schwitters wanted to make something that belongs to no literary or visual category. There’s an oval hand mirror in the show on which he pasted colored paper, cardboard, wood, metal leaf, porcelain, and a few other odd scraps (see illustration on page 10). It is no longer an ordinary mirror; it is a mirror in which our thoughts are reflected as we gaze into it.

The story of Dada in Cologne in the years between 1918 and 1920 is inseparable from the occupation of the city by the British army following the armistice. The foreign military presence, as well as censorship, hunger, misery, and the failure of most civil institutions, created an atmosphere in which the movement prospered. The leader of the group was Max Ernst, an artist first influenced by Picasso’s collages and by de Chirico’s “metaphysical paintings,” who came into his own after encountering in Munich in the summer of 1919 the magazine Dada edited by Tristan Tzara and the abstract and near-abstract works by Klee, Kandinsky, Hausmann, and Marcel Janko. The Dada years were the most interesting in Ernst’s long career and he is well represented in the show. He made collages, worked with photographs, and used pages of illustrated catalogs displaying various kinds of utensils and apparatuses which he then partly covered over with gouache, pencil, and ink until these items were transformed into fantastic imagery we now immediately associate with Surrealism, although both the movement and André Breton’s theories about dreams and the unconscious were still to come.

In addition to Ernst, the show includes the works of two minor Cologne artists, Johannes Baargeld and Heinrich Hoerle. They published journals, Bulletin D and Stupid, and made themselves notorious by organizing an exhibition, “Dada Early Spring,” which the police closed on grounds of obscenity. Those who wanted to view the art had to walk through a men’s toilet in a pub to reach the room in the back where it was hung. Once they got past the urinals, they were met by a young girl dressed for her first communion, reciting lewd poems. Among the works shown, there was a sculpture of hard wood by Ernst to which a hatchet was attached along with the invitation to the visitor to destroy it. The Cologne group broke up soon after when some of its members began to demand a more accessible art and others refused to use art in the service of political ideas.

The New York Dada faction made little news locally. Two bits of scandal occurred, first when when Marcel Duchamp submitted a white porcelain urinal, signed R. Mutt and entitled Fountain, to the first exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, and then when the pugilist and poet Arthur Cravan decided to disrobe on the lecture platform from which he was about to initiate the ladies of Park Avenue into the mysteries of abstract painting. Otherwise, Dadists were hardly visible. The small group of artists who were paying close attention and already had links with avant-garde movements in Europe were either foreign-born or recent arrivals who had come to escape the war. They met at the informal parties at the West 67th Street apartment of the rich patron and collector Walter Arensberg, which housed at that time one of the most advanced collections of modern art ever assembled in the United States, and at Alfred Stieglitz’s photo gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue.

Some of the most famous pieces of Dada’s art came out of that alliance. They include Marcel Duchamp’s readymades and assemblages, Man Ray’s mixed-media assemblages and found objects, Picabia’s “object portraits,” and some intriguing paintings by the little-known artists John Covert, Morton Livingston Schamberg, and Jean Crotti. There are also two sculptures in the show by the legendary Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Lorighoven, who walked around New York with a wastebasket on her head, postage stamps stuck to her face, and her dress ornamented with children’s toys, tea balls, and other trinkets she swiped from Woolworth’s or found in the streets.

Because they have become so familiar, Duchamp’s famous readymades no longer shock. What keeps our interest is the titles. It must have been his sense of humor rather than his much-praised intellect that caused Duchamp to exhibit an ordinary snow shovel and name it In Advance of Broken Arm. When Picabia drew a sparkplug and called it Portrait of a Young American Girl in a State of Nudity, he knew there is no better way to draw attention to the aesthetic side of a mass-produced object than to connect it to sex. Advertisers of everything from cars to toothpaste have always understood that much. This is the homegrown aspect of New York Dada. They hoped to make a hardware store window, with its pots and pans, screwdrivers, hammers, knives, electric fans, paint buckets, plungers, dustpans, and brooms, more interesting than a visit to a museum, not least by renaming each object.

Dada came to an end as a movement in Paris in 1921 despite its furious public activity and the presence in the city of Tzara, Arp, Ernst, Duchamp, and Man Ray. Just in the first five months of 1920, there were six group performances, two art exhibitions, more than a dozen publications, and a great deal of attention in the press. Notwithstanding their success, there were squabbles from the moment Tzara arrived from Zurich. In place of a community of exiles, he found in Paris an avant-garde with strong native roots and not a little xenophobia. The French Dada was led by the poets André Breton, Louis Aragon, and Philippe Soupault, who saw themselves as heirs to Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Lautréamont, Jarry, and other French rebels of the past and whose chief ambition was to revolutionize French poetry. The calculated provocations and the hysteria of the hostile public all became predictable. Ridiculing bourgeois cultural tastes can be amusing but is not as dangerous as mocking militarism in a time of war.

In the end, the poets and the painters went their separate ways. Or rather, the artists continued doing what they had been doing all along. A distinct Paris Dada style never emerged. Man Ray’s flat iron with a row of tacks glued on the bottom, his metronome with a cutout photograph of an eye on a pendulum, Duchamp’s Mona Lisa with a mustache and a goatee, or Ernst’s oil-on-wood construction Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale could have been done anywhere. Dada’s genius was that it refused to define itself and become an art movement in an era of proliferating avant-gardes. All that its artists had in common were a few ideas about going beyond pictorial conventions, freeing art of its history in order to discover it elsewhere, as well as a sense of humor. That made all the difference—what Harold Rosenberg called “comical questioning of appearances.”10 One only has to watch films like René Clair and Francis Picabia’s Entr’acte, which are part of the MoMA show, to realize that their patron saint was that other mad twentieth-century inventor of visual gags, Buster Keaton. The joy of seeing this exhibition is the discovery of little-known works of art, which once were not supposed to be art, but which now look marvelously ingenious, well-made, and even beautiful.

This Issue

August 10, 2006

-

1

Hugo Ball, Flight Out of Time(University of California Press, 1996), p. 64. ↩

-

2

Ball, Flight Out of Time, p. 70. ↩

-

3

Ball, Flight Out of Time, p. 56. ↩

-

4

Herschel B. Chipp, Theories of Modern Art: A Sourcebook by Artists and Critics, with contributions by Peter Selz and Joshua C. Taylor (University of California Press, 1973), p. 391. ↩

-

5

Chipp, Theories of Modern Art, p. 286. ↩

-

6

The Dada Painters and Poets, edited by Robert Motherwell (Harvard University Press, 2005), pp. 81–82. ↩

-

7

Kurt Schwitters, PPPPPP (Exact Change, 2002), p. 215. ↩

-

8

The Dada Painters and Poets, p. 92. ↩

-

9

Brandon Taylor, Collage: The Making of Modern Art (Thames and Hudson, 2004), p. 39. ↩

-

10

Harold Rosenberg, Art on the Edge(University of Chicago Press, 1983), p. 180. ↩