Just when we think that we have seen enough works on paper to have some sense of the possibilities and the limits of what paper can do, the poet Mark Strand’s beautiful collages—made in Madrid, where he lives—make us realize how profoundly we’ve underestimated the remarkable feats of magic that can be performed by some wood pulp, or rags, water, a few chemicals—and the hand and eye of an artist.

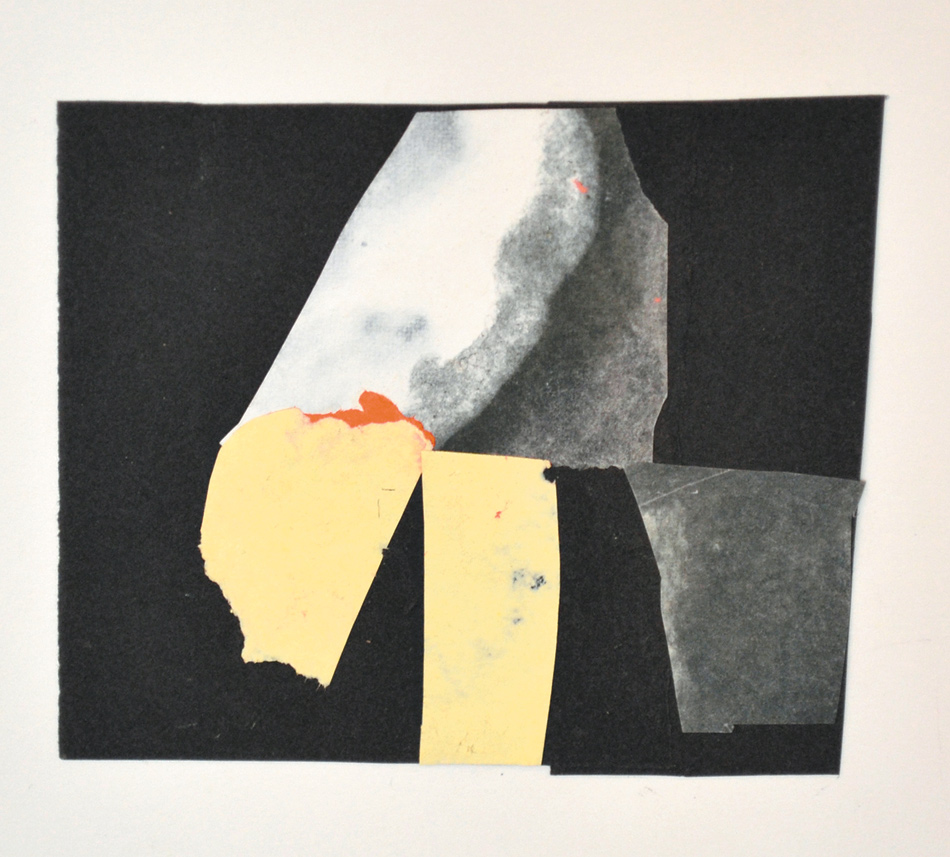

Made from pieces of handmade paper, sometimes painted, Strand’s work is very different from that of Picasso, Matisse, and Kurt Schwitters, whose papiers collés, cut-outs, and collages often seem intended to make us aware of the origins and previous functions of their component parts, cut from sheets of wallpaper, colored paper, and newsprint, or, in the case of Schwitters, sometimes assembled from detritus found in the street. Who would have dreamed that torn scraps could speak to one another, exchanging playful, private jokes? Who could have predicted that fragments of paper could appear to glide and migrate across the page, to attract and repel one another, even when we know (or think we know) that they are firmly fixed in place? Who knew that abstract paper shapes would have so much to tell us about the fortuitous cooperation of chance, accident, intention, and aesthetics, about the complex partnership between the artist and the paper itself? Who would have imagined that a colored sliver of paper could deepen and enrich the color of its neighbors, or how surprised a color could seem to find itself beside a very different hue, or how obligingly these colors could change in response to their environment, like a newly identified species of ragged, two-dimensional chameleons?

The paradox and the marvel of these works is that they are immensely sophisticated and at the same time have the power to remind us of our own earliest encounters and experiences with color and form. Though they are unlike any other work, unlike anything but themselves, they reach back into art history and evoke faint echoes of Klee, Miró, Mondrian, early Guston, early de Kooning, Clyfford Still, Conrad Marca-Relli. Knowing, conscious, thoughtful, they still manage to retain, and remind us of, the innocence of those moments when we, as children, were first astonished by the color wheel, by transparencies, by the rainbow, by the amazing discovery (which each of us secretly believed that we were the first to make) that blue plus yellow equals green.

Strand chooses to say nothing about the connection between his poems and these collages. But the writing and the visual art are clearly the work of the same person, marked by qualities as unique and recognizable as a fingerprint. They share a very particular elegance, a mysteriousness, a melancholy leavened by grace notes of humor, and the ability to make the precise and artful look effortless and fluent. Above all, these collages, like Mark Strand’s poems, show us how much beauty can be discovered by an artist using simple implements—a pen, a brush, a pair of scissors—like navigational tools to guide him across the daunting wilderness of the blank paper, the empty page.