In response to:

A Special Supplement: The Old School at The New School from the June 18, 1970 issue

To the Editors:

when on the eighteenth of this month [June] The New York Review of Books offered a report on Princeton’s reaction to the Cambodian crisis and a parallel one about events at the Graduate Faculty of the New School for Social Research, no reader could escape the conclusion that what worked well in Princeton turned into a rather deplorable event at Fifth Avenue. Both articles were written by faculty members involved in the happenings in their institutions; yet, what a difference from here on! Professor Stone had the advantage of being able to impart good news and to report on spontaneous events which nevertheless were structured in an orderly manner easier to survey than the somewhat chaotic ongoings in the building formerly known as Lane’s Department Store.

While Princeton succeeded in setting up a strike of the university, not one of the students against the university, the Diamond and Nell article leaves no doubt that, in the minds of its authors at least, this was in addition a strike of the New New School against the Old New School. Whenever the two authors keep to factual events, I am quite willing to take their word for what happened. They were there, I was not. However, the hypotheses advanced in explanation, the major one contained in the title of the article itself, appear to me rather dubious. By citing the inscription of the bronze plaque in the lobby of the Graduate Faculty, the authors set up the school’s image of itself. This takes some doing, but it is done following the old routine of “now you see it, now you don’t.” Now every reader of The New York Review of Books is the fortunate owner of the Graduate Faculty’s catalogue for 1969/70. Yet, to read the first columns of the article without recourse to that valuable booklet must lead the reader to strange conclusions. From 1933 on, 167 scholars were rescued from political persecution at home by calls issued by the New School. Some moved on, some stayed. This is followed by a roster of forty-eight names: the original faculty….

So far you can see it, and now you don’t: for the unsuspecting reader at this point is plunged into the hypothesis underlying all theorizing of this article. He is presented with the villain of the piece: the Old New School of “the Platonic mystique as opposed to Socratic engagement.” Apart from wondering what might have been on the authors’ minds when they coined so felicitously nonsensical a phrase, the reader may now begin to wonder in all seriousness. The year 1933 is an awfully long time ago. Should the “Old New School” have enjoyed disproportionate longevity when compared to the rest of mankind? But no, the reader recalls: some moved on, and five were added by way of footnote. He is also informed that right now 2,500 students are taught at the Graduate Center by a permanent faculty of thirty-eight.

Obviously, quite a few members of the “Old New School” are no longer around. And now the catalogue comes in handly in some simple arithmetic. It lists as regular faculty five names from among those branded as the “Old New School.” One of them, Hannah Arendt, is listed as on leave for 1969/70, which leaves four. In addition, there appear the names of two professors emeriti as still active as teachers, both included in the roster on the plaque: Professors Lowe and Kallen. Professor Horace M. Kallen received his Ph.D. at Harvard in 1908, hence he cannot be classed as an émigré. This leaves one teaching professor emeritus, and we come up with the grand total of five professors presumably forming the present “Old New School.” Five out of a total of thirty-eight. But these five, we are made to believe, not only formulate the self-image of the Graduate Faculty as it now stands, but they and their predecessors cultivated only a few students fitting into their rigorous German mold, a procedure acceptable only to “an unconventional student body.”

As for the rest of the gloomy past: there was estrangement among students and faculty, illusions about students on the part of those ex-Europeans, and a body of harried night students who were unable to practice “German rigor.” All these ex-Europeans, we are told, had one central event in their lives, namely a traumatic rift with their homeland. They did not serve their students as good American, professors should, they buckled under at the whip crack of authority without serious question—a European serfdom syndrome, no doubt?—they were status conscious, and they drew strength from a mythos of persecution. What is more, the Cambodian strike debacle was all their fault. Theirs and that of the administration. Unfortunately for the theory, all major administrative offices have been in the hands of non-immigrants for about a decade. But we all know what administrators are like anyway, don’t we?…

To sum things up: it may be entertaining to build up a straw man and knock him down. But it does not advance the cause of truth nor does it shed any light on anything at all except on the authors predilections in journalism. The second strike week at the Graduate Faculty clearly was “a bad scene.” But this cannot be laid at the door of the “Old New School” since as of this academic year there were only five persons eligible in this illusory club over against thirty-three full-time faculty members who weren’t. To put it more colloquially: are you kidding? What is more, the description of the Graduate Faculty’s past simply does not square with the facts. Once upon a time, hard to imagine perhaps but nevertheless quite true, there were no 2,500 students who had to make do with only thirty-eight regularly appointed faculty members. Classes of twelve people or less were the rule, and if German rigor prevailed in them those students welcomed it. Admittedly, they were an unconventional bunch, not like those nowadays who “resemble others in the country,” Incidentally, if I were a graduate student at another respectable institution right now, I would resent the implication contained in this particular passage. As far as estrangement in those far-off days, let me say this much: neither Professor Diamond nor Professor Nell seems to have been around the New School then, i.e., up to about ten years ago. They may have been busy then earning their respective Columbia and Oxford degrees, and here I have an advantage. You see, I was there from the early 1950s to 1961 as one of those “harried night students,” getting my BA there (they did have a BA program then, you know) and later an MA. Estrangement, bullshit! Hardly anywhere else in the US did you get the personal attention in graduate school as at the Graduate Faculty. It simply won’t do to project present impressions back into history while at the same time berating a phantom faculty which could not possibly have dominated faculty meetings in the period from May 30, 1970, to the end of the spring semester.

That those 2,500 students, and incidentally the thirty-eight faculty members as well, should feel estranged from each other now I do not doubt for a moment. But that was not the main point of the article.

As a conclusion, let me offer a few suggestions as to the more probable causes of the New School’s difficulties during the strike. First, as Professor Stone pointed out in his Princeton article, mass movements at educational institutions in big cities are harder to coordinate and keep within defined bounds than in isolated college towns.

Secondly, misgivings as to the propriety of university involvement in politics need not be of foreign origin or arise from the trauma of an immigrant. It is a matter of checkable record that such misgivings were voiced at any and all colleges and universities where the question of the strike was debated in any seriousness. It is an eloquent and moving testimony to the overriding urgency felt by many in this matter that peaceful demonstrations did take place in so many places and compromises between diverging views could be established. Those uttering those misgivings were just as concerned about the world and the role of the university as the other side. What is more, neither side can be proven right or wrong in this once and for all. The chaotic events, the blunders committed at the New School should not be blamed on thirty-eight faculty members plus administration nor on the “reactionary forces” within that group during those two eventful weeks.

What is deplorable and what finally did contribute to the course of events is that the New School in its otherwise distinguished history never managed to set up a representative student government. This was a fault in the past but understandable then. When most of the teachers and the School’s president were Europeans, they were unfamiliar with student government procedure since they had had none in their day. Since at the same time, the setting was intimate, the School, both graduate and undergraduate divisions, managed to muddle through without that. During the last decade, this omission has become inexcusable and, as events have shown, ultimately harmful to the School itself. For one thing became clear during those crucial weeks: any school with an organized and well-coordinated student government was infinitely better off in coping with unusual demands and decisions than schools with badly run organizations.

When it came to a crisis, everybody at the Graduate Faculty must have come to the realization that one could not be sure that those feeble student clubs were really speaking for the students at large. You cannot be politically effective, keep the good will of the faculty and administration and thereby have access to rooms and facilities by running impromptu meetings of people who afterward cannot speak about anything but their individual wishes, dreams, desires, and demands. Nor can any halfway reasonable person blame the faculty or members of the administration when they feel irritated, frustrated, and genuinely unable to come to amiable agreements—with whom? These meetings may have been exhilarating for most participants, but the purpose of the nationwide strike was not to provide “ego trips” but to lead to effective, long-range political action. The encouragement and aid of the School to the formation of a proper student government should be of overriding concern to any and all at the New School—never mind the particular difficulties inherent in this task at this particular institution. By now, it should have become clear that this has become a matter of survival. Also, administrations may take great satisfaction in an enormous increase in student enrollment. But if this means that a faculty-student ratio of about 1:12 deteriorates to one of 1:65 in a decade, then matters may be profitable, but nobody should be really surprised if they become also explosive in a crisis. This, to my mind, is the obvious construction to be put on those events….

Sabine D. Jordan

Department of German

Connecticut College

New London, Connecticut

Stanley Diamond & Edward Nell replies:

The bulk of this letter is irrelevant; refuting it point by point would be a tiresome and sectarian exercise. The presentation of our views is a parody, e.g., the arithmetic is beside the point; we are talking about an ethos. We do not imply that the New School was not intellectually exciting. On the contrary we think that it was and is. But the issue concerns authority and style, not intellect.

The letter, however, does attempt an alternative interpretation of the events at the New School which we believe to be entirely false, and that deserves a few words. Essentially Mrs. Jordan argues that the problem is primarily administrative, a matter of the ratio of faculty to students, compounded by the lack of a formal student representative government. Political issues, if not wholly irrelevant, appear, in her judgment, to be inconsequential.

This is simply not the case. No doubt a student union, student participation in administrative bodies, and other means of student representation and self-government, for which we have been arguing during the past year, are necessary. The student departmental club system at the New School is not adequate. Nor have the mechanisms for student participation in administrative decisions been worked out in a formal and responsible way. A number of alternatives are now being examined and, one hopes, that problem will be solved during the course of the coming year. But the events of May were part of a larger national, indeed, international movement, and find root causes in the character of our culture, including the academy, and a proximate cause in American adventurism in Southeast Asia. We undertook a serious analysis of the crisis in one particular microcosm, and systematically explained the reasons for our local variation on the national case, e.g., the territorial conflict over limited facilities.

According to the summary report in The New York Times of July 4, 1970, Dr. Alexander Heard, the Chancellor of Vanderbilt University and Special Adviser to the President on student unrest, offered the following views:

The student revolt may seem baffling and chaotic to outsiders but underneath it is a deep moral commitment, a seriousness of purpose, to eliminate what the students genuinely believe to be the weaknesses of American society…. Given the integrity, idealism and passion of the students, the Administration would be well-advised to listen to them and ill-advised to attempt to make political capital of the disturbances they cause…. [T]he perceptions of the men who run the country as to what is important, and the priorities of the next generation are radically different…. [T]he concept of an ‘honorable’ settlement in Vietnam, important to the President, strikes the student generation as insane because, in its view, American participation in Vietnam is itself dishonorable.

This report indicates the depth of student commitment; a previous report in The New York Times (May 29, 1970) gave some indication of its extent: Charles H. Hitch, President of the University of California, addressing the Commonwealth Club of San Francisco, stated that for the first time student protest on University of California campuses encompasses a majority of the academic community.

The Cambodian operation and the shock of Kent State and Jackson State have galvanized the campus population…. [I]n contrast with past years, when outsiders outnumbered student protesters, today’s protests involved engineers as well as humanities students, athletes as well as student government officers [italics added], sorority and fraternity members and many other student groups that have not until now been activists.

We commend the views of Drs. Heard and Hitch to Mrs. Jordan.

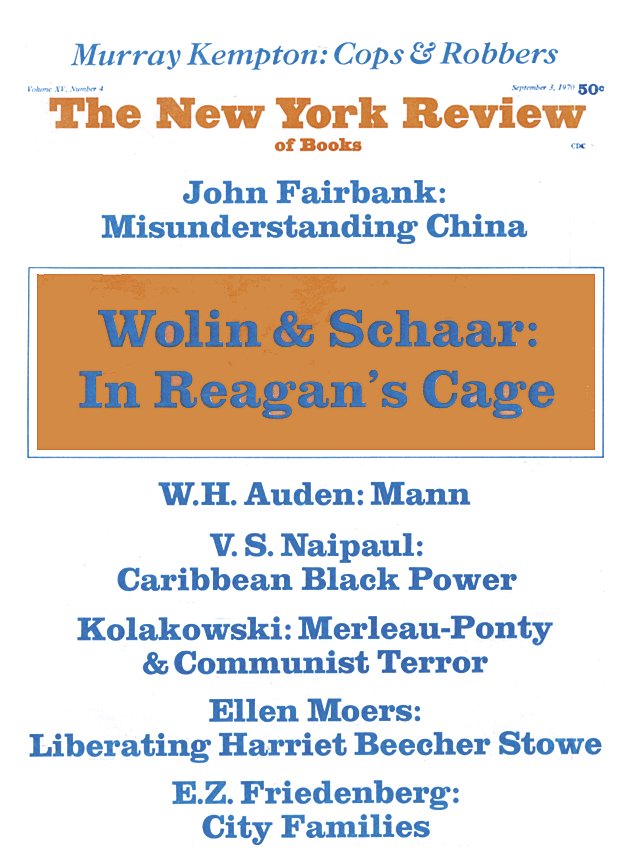

This Issue

September 3, 1970