Youth from the past. Un adolescent d’autrefois was the original title of Maltaverne which Mauriac published in 1969, when he was eighty-three, a year before his death. For the last thirty years of his life he had written very little fiction, preferring to concentrate on essays and perhaps ephemeral political commentaries. Finally, in Maltaverne, he recapitulated with authority the themes of his prewar novels, marrying the skill and experience of his great age with a fresh, youthful expectancy to produce a fitting conclusion to his life as a writer. If nothing else, it is a polished and powerful piece of storytelling. The energy and cunning of this old craftsman, so near to death, is an encouragement to the living.

Sartre once complained of Mauriac’s tendency to shift his viewpoint, to describe a character sometimes from the outside, as a third person to be observed, sometimes from within, as if identified with the author. “Fictional beings,” wrote Sartre, “have their laws, the most rigorous of which is the following: the novelist may be either their witness or their accomplice, but never both at the same time.” This law, as Conor Cruise O’Brien has suggested, is surely too rigorous; it is evaded, rather than broken, in Maltaverne.

The principal character and narrator, young Alain, is clearly a reflection of the author himself, in the years 1904-1907: the boy’s vivid presence may possibly owe something to the author’s consideration of his own youthful letters and journals, but Mauriac is selecting from the boy’s opinions and feelings those of most interest to himself, sixty years later. Alain says: “Old men are horrible, when they can’t keep away from young people, it makes you sick, aging writers who dare talk about it in their books, who’ve no shame.” By “it” here, Alain means youth and physical love. Sometimes he stares at a very old man, in 1904, and tells a story about him—which becomes more and more improbable, until he admits to the reader: “I made it up.” Then Alain imagines himself at the same age—“still the same person that I am now, while some child-poet in 1970 will watch me from a distance, as I sit motionless, in my doorway, turned to stone.”

His friend, Donzac, supposes that Alain may become a great writer but will never achieve what is most desirable, the religious understanding of “that secret point where the truth of life as we experience it joins revealed truth.” Donzac—for whom, Alain suggests, the story is written—makes no appearance, though he is often referred to as an austere guardian of standards so high that there is no great shame in failing to meet them. More deflating than Donzac is another of Alain’s young friends, a peasant-boy seminarist called Simon, who tells Alain: “You’ll still win the first prize for composition in 1970.”

Max Beerbohm drew some quite witty cartoons of writers like Browning and Wordsworth, with the older “self” confronted and criticized by the younger “self”—like a father challenged by his son or patronized by his grandson. (I read, in an obituary, that “Mauriac, although respected as a stylist, was barely tolerated by young French people of the Sixties.”) Mauriac’s vigorous old age and powerful memory lend credit to Alain’s contention that the older and younger selves are “the same person,” despite his fear that “people are divided by differences of age or social class to such an extent that there is no common language.” In English, age is something you are; in French it is something you have, rather as we talk of having class, having character, and, even, having sex—all misleading usages. Age, character, class, race, sex: the boy Alain learns to think of these not as things that we have, property, possessions, but as relationships, things that we do to and with each other—among whom, in Mauriac’s faith, God is included. Having involves being had: he is in danger of belonging to his belongings.

Alain comes from a landed family—in Mauriac’s familiar Landes, around Bordeaux—and this means that he will probably be married to a little heiress, whom he calls the Louse. Age twenty-one, he tells a girl friend that his mother

…has always been convinced that what I call physical love doesn’t exist for creatures of a certain race, to which she and I belong, that it’s a romantic fiction, that sex is a duty required of women by God for the propagation of the species and as a remedy for man’s bestial nature.

The girl friend says: “You’re the property of your property. You’ll marry the Louse.” Alain is frightened of this possibility, remembering Christ’s warning to the young man who had great possessions.

Advertisement

He hates the Louse and indicts his mother for her idolatrous worship of the land—which she thinks “the only legitimate pleasure granted in this world to a woman from one of our families.” He supposes that his own love of the land is quite different and perhaps justifiable, since it refines his appreciation of eternity. His old trees make him “aware of the ephemeral character of man’s condition. One wouldn’t mind being a thinking reed; but a thinking insect who during the few moments it has to live finds time to mate, that’s something dreadful.” While exposing his own pride, he arraigns his mother’s, arranging deadly sins in order.

For Mother, evil consists in those covetous desires from which in fact she is immune, which she calls concupiscence and for which she feels only repulsion. She never thinks of sin in connection with her own pride in possession and domination.

The reader’s sympathy with Alain, for all his casuistry, is cunningly moderated by the author, discreetly urging the mother’s case against the line of Alain’s argument and hinting that, if “sin” is under such close scrutiny, it is particularly sinful to call a little girl a louse.

The pattern of Alain’s thinking and behavior is set out. Then Mauriac shows the results, in a cruelly moving piece of narrative. The Louse is horribly killed, through Alain’s fault, and at twenty-two he thinks he has already “crossed the line beyond which one no longer seeks to be happy, but to gain control over one’s life.” His plan for self-subjection involves writing about his experience, even though “the outcome of all this agony will be a three-franc paperback.” He says: “I alone am capable of seeing that none of it is wasted…. What other young man had a mother like mine, and what other carries in his heart the image of a defiled and strangled child?” Yet the story of this defeated man ends, as it began, in a spirit of expectancy and youthful freshness.

Alain’s bookish girl friend says that certain elements in his character come from Christ but are “inseparably blended with those that come from Cybele.” Mauriac has written elsewhere that “Cybele has in France more worshippers than Christ.” Perhaps he identified the Great Mother with Mother Church—which, “with all its crimes and all its holiness,” says Alain, “is the most beautiful thing in the world.” Alain has learned from Donzac “that the Christians who have brought us up take, unconsciously, the opposite line to the Gospel in everything, turning each of the Beatitudes in the Sermon on the Mount into a curse; that they are not meek, they are not merely unjust but they execrate justice.” The priests and teachers are idiots. “All the same, what they believe is true. There you have the whole history of the Church.”

Although I happened to be rereading War and Peace when I took up Maltaverne, I did not feel, as would be expected of a modern novel, that something immeasurably inferior had interrupted; nor that time had erected a great barrier between Tolstoy’s 1812 and Mauriac in 1970. It is evident that Alain could talk unconstrainedly with Bezuhov and Prince Andrei, as most of us could not. (Tolstoy was still alive in Alain-Mauriac’s adolescence.) Alain is certain of his identity; an undivided self, he thinks he is a “soul,” committing sins. His sex and his class are forces to be reckoned with, to which he will often surrender, prompted by his pride, anger, and sloth. But his faith makes him feel free. Arguing the case for predestination, within “the unconscious, universal swarm-life of mankind,” Tolstoy still confidently asserted that each man has another side to his life—“his individual existence, which is free in proportion as his interests are abstract.” Alain has this kind of confidence, rare in more modern fiction—unless we count Beckett, and choose to find his work optimistic.

The circumstances in which we read a book are bound to influence our appreciation. I had been studying mental illness in Malta, seeing how Roman Catholicism can help to keep people feeling “sane” (if not “adjusted”) and Maltaverne illustrates this: the Beckett-like pessimism of the story acts as propaganda for the Church’s optimism. But that Church can also drive some people to distraction—as is illustrated in another account of a Catholic childhood, The Manuscripts of Pauline Archange, by the French-Canadian novelist, Marie-Claire Blais. Out of sight of land, I kept discussing this contrast with shipmates, as we sailed slowly toward fascist Greece—where respectful interest in organized religion is immediately dispelled by the ubiquitous presence of the colonels’ nauseating placards: “A Greece for Greek Christians.” Returning to agnostic England, I found that Mauriac was dead—and, for all I know, gone where he said Gide would go—and that I had another Catholic novel to review, Muriel Spark’s The Driver’s Seat, a bleak fable about insanity and what they call Evil. I must start writing again, in a cooler, British environment.

Advertisement

Muriel Spark’s novel is about a respectable woman from “the North” (probably Britain) who flies to “the South” (Italy? Greece?) to commit her chosen sin. This is not uncommon: the churchmen of the South are inclined to avert their eyes from tourists’ sins. But Miss Spark’s heroine—an office-worker called Lise—has an unusual craving: she wants to be the victim of a “sex-crime,” a perverse murder. We are given no explanation. We are not told from what cool town she comes, nor in which hot town she dies. She is a thin woman, aged between twenty-nine and thirty-six, who has deliberately made herself conspicuous with clashing, gaudy, holiday clothes, carefully selected for their lack of stain-resistance. She is observed, overheard, by no means understood. She seems ordinary, if eccentric, to other characters—except to a fellow passenger on the aircraft, who moves his seat, horrified by the temptation she presents to his sadistic nature. She comments:

He must be nutty. He wasn’t my type at all and I wasn’t his type. Just as a matter of interest, I mean, because I didn’t take the slightest notice of him and I’m not looking to pick up strangers. But you mentioned that he wasn’t my type and of course, let me tell you, if he thought I was going to make up to him he made a mistake.

The banality of her style seems unnatural to her, like a parody of colloquial speech. She keeps looking for her “type,” someone to match her fantasies. When she finds him, she gives precise instructions: “I don’t want any sex. You can have it afterwards. Tie my feet and kill, that’s all.”

In Muriel Spark’s fiction, the word “sex” often sounds unnatural—as if physical love were some primitive rite, to be observed by an anthropologist: one of Miss Brodie’s girls was said to be “famous for sex.” Or imagine a very old lady who has picked up ugly slang from the television and uses it shamelessly, unshocked and uninvolved. Muriel Spark’s tone is comparably prim, chilly, and alarming. Expressions of human sympathy are resolutely excluded from the narrative, until the final sentence—when the sex-killer, Lise’s “type,” glimpses the policemen with their “holsters and epaulettes and all those trappings devised to protect them from the indecent exposure of fear and pity, pity and fear.”

The left-wing and libertarian press of the “underground” is full of photographs of long-haired youngsters brutalized by policemen. Sometimes we meanly suspect that the martyrs were asking for it, more concerned with living out their fantasies than dying for the cause. Muriel Spark isolates this element. Lise submits to maltreatment not, like Mauriac’s mother, as “a duty required by God” nor, like Jesus or the Unknown Warrior, as a supreme sacrifice. She submits because she wants to. As Lord Melbourne said of the Order of the Garter, “There’s no damned merit about it.” Lise’s quest recalls a poem by Thom Gunn, about sadists and masochists:

I see them careful, choosing limita- tion,

And careful still to break their loneliness

Only for one who, perfect coun- terpart,

Welcomes the tools of their per- versity.

Unexplained, as if inexplicable, The Driver’s Seat gives us the kind of frisson which ghost stories give to children. It is perhaps Muriel Spark’s most successful attempt to represent Evil personified. She told us too much about Mrs. Hogg in The Comforters, and for Miss Jean Brodie we felt a positive liking; but we are told so little about Lise that she becomes frightening through her mystery, like some incomprehensible patient in a mental hospital who seems activated by nothing but malice. Muriel Spark’s success may be compared with that of Angus Wilson: in his first novel he tried unsuccessfully to personify Evil in the solid characterization of Mrs. Curry; but in The Old Men at the Zoo he succeeded—with a mere vignette, a thumbnail sketch, of Mr. Blanchard-White, the unexplained fascist. “Evil” is perhaps a word for bad behavior which we do not understand.

Our third Catholic novel, The Manuscripts of Pauline Archange, begins by characterizing some Canadian nuns as “the chorus of my distant miseries, ancient ironies clothed by time with a smile of pity, though a pity that faintly stinks of death.” At once we recognize a translation from the French. The first three sentences slowly unroll, almost filling two pages, like parodies of Proust. The length of the sentences is extended by the repetition of similes—each nun has “slim brown boots glimmering like furtive breaches of propriety” and a forehead “betraying like some secret frivolity its dark lock of thick hair”—by unnecessary adjectives and adverbs, and by rambling parentheses. Here is part of a later sentence:

…on the contrary, the consoling energy these women deployed—rigorously masculine in their flat-heeled shoes, in their narrowly cut suits beneath which pointed buttocks provided further expression of their will and daring, yet rigorously maternal too, even though they cloaked that vulnerable quality beneath a soldierly appearance itself extremely fragile—on the contrary, their energy, their restless vigor seemed to contain for us the very element of sturdy tenderness of which we had hitherto been deprived.

She is talking of Girl Scout leaders. Lady Baden-Powell herself, “the grande dame of the Girl Guide movement,” makes a personal appearance, under the pseudonym “Lady Baron Topwell.” The narrator, with other little girls, prefers these “frankly mannish” leaders to the fearsome nuns.

The idea of death, of our childhood sacrificed in the light of a noble setting sun, our bodies pierced with arrows, our heads falling under the ax, should Lady Baron ask it of us some day not far hence, a myriad such images fluttered mechanically against our fevered temples. Ah! We are yours, do with us what you will, you have such a lovely uniform, such pretty leather boots…. We want to go away with you on your ship. Mother Saint-Théophile will beat us again.

The extravagance of the language may be partly the responsibility of the translator—who certainly offers some extraordinary dialogue. (“Hey there, sly puss, what are you up to? Trying to get a peek at the courting couple? Come in and see me instead, I’m as dull as a toad all alone.” “He often falls into the abyss of drink. A real pig, your uncle, there is no gainsaying it, he drinks all day long.”) But the extravagance of the incidents must be intended. In this Canadian town, torture is the main preoccupation: cats are skinned alive and children beaten until their eyes bleed. Meanwhile, a Genetesque priest makes love to a boy murderer with a vague, cruel smile. As a criticism of a Catholic upbringing, it is too nightmarish to carry weight. It reads like a child’s crude fantasies, worked up by an over-literary adult. Its sensuous appreciation of pain, cruelty, and guilt is so unrestrained as to be finally ludicrous.

Two able American novels deal with the lives and fantasies of workers in the movie industry. There is a modern tendency to represent the force of destiny not as God or Progress or the “History” of Marx and Tolstoy but in the person of a film director or producer, making people play roles and observe themselves. In Play It As It Lays, the moviemakers don’t know what they are doing or where they are going. But Gottschalk, in The Stunt Man, is made to seem all-wise and all-powerful. This director offers protection to a college-educated Army deserter, on condition that he will perform dangerous stunts in his new movie: it sounds like the kind of film Joseph Losey might make, an imaginative action story with ferris wheels superimposed on sunglasses, cars hurtling over cliffs, frogmen pursued by helicopters.

Meanwhile Gottschalk’s cameraman, Bruno, is independently making a rather sadistic pornographic movie which, he claims, offers performers “the chance of exposure without risk. In my films one can live every fantasy without risk.” As for “self-respect,” that is merely “a barrier people erect against the possibility of having to recognize the true self.” The college-boy stunt man discovers that his own real life amours have been sneakily filmed by Bruno, so he beats him up and complains to Gottschalk: “Bruno’s film. I’m in it.” The godlike director wearily replies: “Which you? Each time the shutter clicks, there’s another image of you superimposed on the one that was before.” He does not believe in Bruno’s exposure of “the real self”: he is interested in “double-exposure.”

It is intended that an allegorical significance should be read into the film maker’s metaphors. The stunt man is in limbo, between the dangerous world and the safe screen, where excitement and adventure may be enjoyed without risk. He gets the disadvantages of both worlds, the risks as well as the unreality. Under Gottschalk’s protection, he is disguised in a protective suit intended (in Gottschalk’s movie) not to protect, but to signal to audiences “the theme of hostile environments and the imminence of disaster”—disaster which might really happen to the stunt man as he plays the part of a player enacting his own real situation, disguised as a man in disguise. The relationship between his real situation and his role is played out in his mind’s “private theatre where the windshield before his face became a screen upon which he found himself watching a series of disconnected shots.” The tale needs perhaps clearer definition: the rather stagy dialogue, suggesting mystification rather than a coherent philosophy, has a fuzzy, blurring effect.

More sharply defined is Play It As It Lays. This is the story of an actress, Maria, who has made two movies with her director husband: she likes one of them, in which she plays a girl raped by a motorcycle gang, since the victim on the screen seems to have “a knack for controlling her own destiny”; she dislikes the other, since the character seems to have “no knack for anything.” Yet this picture, called Maria, ought to be a faithful portrait of herself: her husband, Carter, made it by following her around New York while she was shopping, crying, sleeping, or straining marijuana. Though never distributed, Maria won a prize at a European festival. Ambitious students talk about “using” Maria in their own avant-grade movies; her husband’s friend, BZ, a producer, keeps a print of Maria and looks at it in the way he looks at Maria herself, as if he too wanted to “use” the actress in some way.

Maria separates from Carter and becomes uncertain of her role. One day she sits in a park, watching motorcyclists rifling cars. She walks towards them and admires the “choreography” as they fan back into a half-circle: she drives away, feeling that they have shared “an instant of total complicity” which she will play back in her head, changing the scenario. There is also a nursemaid in the park, whom Maria imagines coming toward her with a hypodermic needle. Sometimes she drives aimlessly along the freeway, until that “flawless burning concrete” peters out, stopping at a scrap metal yard or turning into common road, flanked by rusting, abandoned construction sheds. Carefully then she turns around and gets back into the mainstream with its luminous signs. Joan Didion’s cold eye for Californian landscape lends elegance to desolation.

When Maria goes to parties, she is accompanied by “a third-string faggot, never a famous faggot, never one of those committed months in advance to escorting the estranged wives of important directors.” She lists other habits of such wives, and resolves to be different: she would never, for instance, “ball at a party” or “do S-M unless she wanted to.” When she breaks the first resolution, she lands in a Nevada jail. It is implied that she breaks the second: after drinking heavily with BZ and his wife, Helene, she has “a flash image of BZ holding a belt and Helene laughing and she tried not to look at the bruise on Helene’s face.

BZ begins to talk to her: “Tell me what matters…. Nothing.” “You’re getting there…. Where I am.” Finally, in bed with her, BZ commits suicide, after telling her: “You and I, we know something. Because we’ve been out there where nothing is.” Maria goes to a mental hospital, where she says things like: “What makes Iago evil? Some people ask. I never ask…. I am what I am. To look for reasons is beside the point…. Carter and Helene still believe in cause-effect. Carter and Helene also believe that people are either sane or insane.”

We are told more about this credibly deranged woman than about Muriel Spark’s unlikely Lise, and therefore Maria is of more “human interest,” the subject of a novel rather than a parable. Although she seems to be in hell, and although every event is charged with misery, Play It As It Lays will extract no tears and cannot be honestly called depressing. The neat, cinematic construction, the economy and precision of the narrative, and the harsh wit of the mean, soulless dialogue stimulate a certain exhilaration, as when we appreciate a harmonious and well-proportioned painting of some cruelly martyred saint in whom we do not believe.

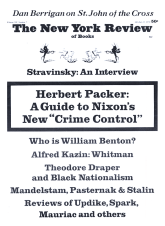

This Issue

October 22, 1970