The architect, practicing the most intellectual of all the arts, prides himself on his ability to relate a bewildering number of variables and assemble them into a design which when you read it convinces you by its logicality. And yet there comes a point when the more brilliant the organization of these variables the less adaptable the building becomes. It fulfills its purpose for a season; but as time passes, social conditions change, and it finally resembles a whale washed up on the shores of history, unusable, a victim of the new environment. Between 1835 and 1889 five hundred country houses of unparalleled size were built in Great Britain, and these are the subject of Mark Girouard’s impressive book. Few of the houses remain untouched or are still inhabited by families. Most have been destroyed or largely pulled down or converted with varying success into schools, museums, asylums, or have suffered other indignities.

The Victorian country house was itself the product of cataclysmic social changes. The rich had become very rich and there were a lot of them: noblemen with bulging rent rolls, merchants, bankers, industrialists, all eager to set the seal of landowner on their wealth. They built houses from the profits of cotton, salt or coal mines, biscuits or ostrich feathers. It was just as well they were rich. Infant mortality among the upper classes had declined rapidly and families of eight to twelve children were common.

There was a limitless supply of cheap labor for domestic service. So every person or pastime or service could be supplied: an infant had its nurse, the nurse her nursemaid, the girls their governess, the boys their tutor, the wife her housekeeper and lady’s maid, the master his valet, gamekeeper, and butler; and the butler and housekeeper had a vast staff under them to serve the rest. The railway brought their friends to their house and they in turn arrived with lady’s maids, valets, and loaders. A great country house therefore was designed to accommodate some forty to fifty people regularly and over a weekend or for a shoot could take 150.

The art of the architect was to organize this mass of human beings into cubic capacities that reflected the social conventions of the times. This meant a series of precise divisions and subdivisions. The family had to be divided from the guests, the men who wanted cigars and to tell stories had to be given rooms for billiards and smoking, the ladies a conservatory and a drawing room. They had to be separated from the elder children who needed a schoolroom and the younger a nursery. The servants needed more rooms than their employers. The housekeeper a still room, store room, and china closet; the butler a pantry, silver room, and a bedroom for the footman to protect the silver; the lower servants a brushing room, knife room, lamp room, scullery, pantry, dairy, and three larders. As for the laundry, six rooms was a minimum for all the processes needed to turn dirty into spotless clothes.

The upper classes had to be separated from the servants to such a degree that houses were designed with quarters and staircases for the servants so decisively sealed off that no gentleman or lady need be at risk of a chance encounter with the lower orders. The lower orders’ bedrooms were arranged so that the bachelor servants had no access to the maids’ corridor. Meals were served in five different places: there would be a breakfast room and guests would never assemble for tea in the room where they had eaten luncheon. Of course, the institutionalization of the social conventions to such a degree was a challenge to the sprightlier spirits which they accepted with alacrity, and in the Prince of Wales’s set the art of the hostess lay in knowing whom to place next to whom in the maze of bedrooms so that night wanderings should reduce social embarrassment to a minimum. The younger servants similarly evaded restrictions when they could—though in that sphere pregnancy meant dismissal.

But encounters with the lower orders or with the other sex were not the only embarrassments which the Victorian country house was designed to exclude. Had the Duke of Devonshire’s Chatsworth been built in Victorian times the young Desmond Mac-Carthy might have been spared mortification. At that age a fervent Tolstoyan, he believed that the worst degradation you could inflict upon a fellow human being was to require him to dispose of your excrement. Accordingly, determined to spare the servants this vile duty, he stole out of his room before eight in the morning clasping a brimming chamber pot, which he intended to empty in a lavatory at the end of the corridor, only to encounter as he turned the corner the Duchess leading the entire house party of female guests to Holy Communion….

Advertisement

Plumbing made an uncertain entry. In 1870 Wykehurst Park was built with bathrooms attached to all family and guest bedrooms. In 1873 Carlton Towers was built without a single bath. The new technology of the industrial revolution produced its innovations—manual elevators, india rubber paving, iron billiard tables, internal telephones—but the most significant was in fact the invention of plate glass and hence of large sash and casement windows and conservatories, though the Gothic Revival houses, of course, reverted to diamond-leaded panes.

But practically no advance was made in central heating. People preferred the cozy open fire of cheap coal. No one solved the problem of ventilating the rooms that became overheated from the pre-incandescent mantle era of gas lighting. The ventilating systems created draughts instead of removing foul air. English country houses were notoriously cold and dank. My mother, a New Yorker, after her first years of married life before the First World War, made an inflexible rule never to visit country houses before Whitsun or after the beginning of October, and the only time she broke her rule and went at Easter, she was unable to digest anything for a fortnight.

Central heating was, of course, regarded as a luxury, and luxury was something American, vulgar and dangerous, as it might give the middle classes wrong ideas about their betters. But, as with plumbing or fitted cupboards, there were wide variations and a good deal of money was slopped about ostentatiously. Mark Girouard has a theory that at the beginning of Victoria’s reign the Man of Taste who built a house to display his paintings, sculpture, and other acquisitions from the Grand Tour began to be replaced by the Christian Gentleman of whom the first Duke of Westminster was so conspicuously an example (and the second equally conspicuously not). You no longer put your house on view, you built a home to enshrine the domestic virtues; and precisely because you abandoned any amateur pretensions to pronounce upon works of art (another outward sign of luxury), you abandoned, as a client, the imperious Georgian habit of instructing your architect and landscape gardener to achieve certain effects.

The age of the architect-dictator had dawned: the Institute of Architects was set up in 1834 and was allowed to add to its title the precious word Royal in 1866. Burn, Blore and Salvin, and later Devey, Webb and Nesfield, and Giles Gilbert Scott were so discreet and gentlemanly that they never exhibited their designs—their names were whispered by one client to another. Blore and Salvin built exclusively for Tory families. Barry built for the Whigs and was a publicist—as were Norman Shaw and Wyatt who condescended to build for the new rich. These were the men who banished stucco as an abominable fraud, who exposed bricks using polychromatic patterns, who were prepared to build in six or seven different styles, and who more often than not could remain indifferent to any miscalculation of the cost of these immense mansions because the client was able and willing to pay the difference.

Toward the end of the century tastes began to change. The last home recorded in this book was built in Sussex for a solicitor by Philip Webb, the socialist architect. Historic styles, ornament, and grandeur were out. The new model for a country house was not to be a “seat” but a farmhouse. Gables, rough cast tower, weather boarding, leaded lights, simple moldings, and painted paneling were now to be the vogue. Nothing was to be pretentious, all was to be light and friendly, and a Puritan abstemiousness restrained any temptation to frivolity or exuberance. There is something symbolic about the choice of a farmhouse as the model. British agriculture had collapsed, rents had fallen, landowning was no longer profitable. The earlier fantasies of the rich, for instance to build a castle and pretend to be a medieval baron, were now to yield to a new dream world of living as a prosperous farmer. There is a good deal to be said for the theory that unbridled capitalism makes men mad.

I am not sure that Mr. Girouard convinces me that the taming of the aristocracy and upper classes by Christianity affected their relations with their architects to a great extent. The architect had his way because the sheer problem of organizing all the variables in the building was beyond the competence of an amateur. But he has written a masterly book. Not only does he discuss the social and technological conditions which shaped these buildings. He also adds the detailed history of twenty-nine of them together with a host of photographs and plates. The book is as handsome as the houses themselves are purported to be.

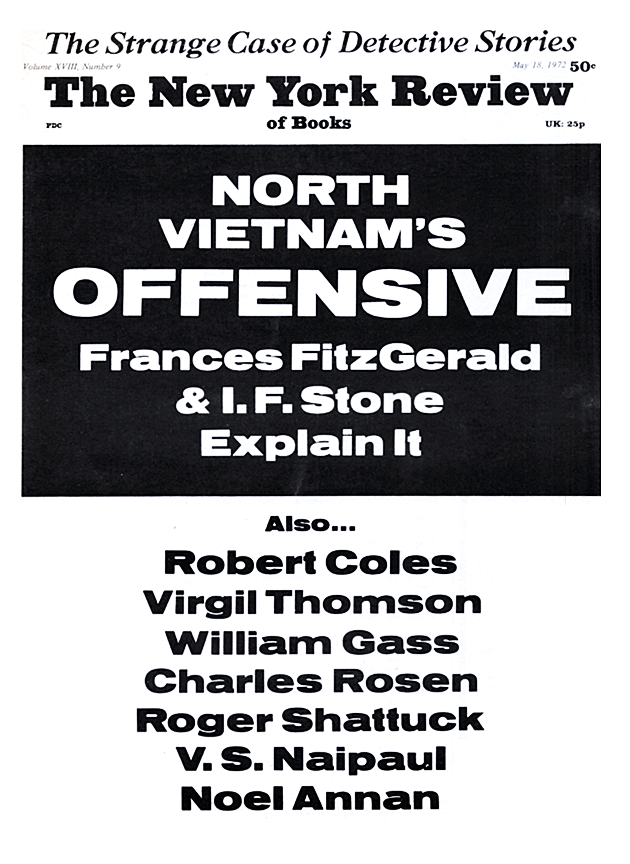

This Issue

May 18, 1972