During the past few years, no French poet has received more serious critical attention and praise than Edmond Jabès. Maurice Blanchot, Jacques Derrida, Jean Starobinski, and others have written extensively and enthusiastically about his work, and as time goes on the list continues to grow. Beginning with the first volume of Le Livre des Questions, which was published in 1963, and continuing on through the other seven volumes in the series,* Jabès has created a new and mysterious kind of literary work—as dazzling as it is difficult to define. Already his writings have been given such a central place in France that Derrida has been able to state, flatly and without self-consciousness, that “in the last ten years nothing has been written in France that does not have its precedent somewhere in the texts of Jabès.” Rosmarie Waldrop’s translation of The Book of Questions can therefore be taken as an event of considerable importance.

Nevertheless, there are inevitably certain difficulties. For The Book of Questions is bound to seem a strange and baffling work to Americans, and a reader who does not have a solid grounding in contemporary French poetry and criticism might find himself at a loss.

The very design of the book in English suggests the problem of cultural transference. The publisher has cleverly chosen to use a cover that imitates the classic Gallimard design: the author’s name in black, the title in red, bordered by one black and two red rectangles. One cannot look at the book without being reminded that its origins are French—as if this were an excuse for its strangeness. At the same time, the American printer has botched the imitation. It is all a question of millimeters, of course, but in the American paperback edition the black and red rectangles, which are always perfectly balanced on every Gallimard book, are askew. There is too much white showing on the left and not enough on the right, too little on the top and not enough on the bottom. This failure to respect the geometric precision of the French edition throws the design off, and the result is disconcerting.

Something similar happens to Jabès’s style in English. This is not through any fault of Mrs. Waldrop’s: her translation is careful and intelligent. In many passages, however, the elevated tone of Jabès’s French comes across as bombastic in translation, partly because the mode in which he writes has all but disappeared in English. We have become so accustomed to irony and understatement that the rhetorical flourishes and poetical excesses of The Book of Questions are occasionally off-putting. At times, Jabès comes out sounding like bad Whitman.

Yet the power of the book remains intact. Jabès is a bold writer, and his lapses into overstatement are more than compensated by his firm control over the structure of the book. Like René Char, the dominant French poet since the war, Jabès writes in an epigrammatic, metaphorical, and elusive manner—a stylistic tradition in France that goes back several hundred years—and, like Char, he runs the risk of sententiousness. Yet unlike much other contemporary French writing, which is so often pinched and cerebral, Jabès’s work has a robustness that is altogether refreshing. His originality—and here one need only think of the pedantry of the Tel Quel poets and some of the more obscure formulations of the Structuralists—lies in his ability to bring abstract ideas to life, to give them clear and palpable shape, and then to connect them to human concerns beyond the realm of mere literary theory. For all his sophistication and all the difficulties his work presents, Jabès is a poet with feelings so intense that they are bound to disturb.

The Book of Questions derives from two traditions. One is what can be roughly called the Mallarméan tradition in French poetry, which is above all characterized by a fundamental examination of writing itself. It is a reflexive, self-conscious mode in which questions of language, of the reality of “the book” (after Mallarmé’s famous dictum that the world exists to be in a book), and poetic utterance are treated as legitimate subjects and not simply as empty formal concerns. There has been no equivalent poetry written in America or England, and nothing in our literature can prepare us for the particular metaphysical and lyric intensity with which the French have approached these problems.

On the other hand, there is the impact of Jewishness, and the Holocaust, on Jabès’s work. To some extent, The Book of Questions can be read as a response to Theodor Adorno’s remark about the “barbarity” of writing poetry after Auschwitz. Adorno’s meaning was clear: in the face of total evil, the writing of poetry (which in normal times is taken to be the purest of activities) becomes an act of transgression. From this point of view, the Holocaust must be considered beyond the grasp of language, as something that can be answered only with silence.

Advertisement

Jabès speaks about the Holocaust, about Jews in concentration camps, but in such a way that he implicitly acknowledges the impossibility of speech. The result is a book that fits no convenient literary classification. Neither novel nor poem, neither essay nor play, The Book of Questions is a combination of all these forms, a mosaic of fragments, aphorisms, dialogues, songs, and commentaries that endlessly move around the central question of the book: how to speak what cannot be spoken. This is the fundamental question of Mallarmé, who insisted that “whatever is sacred, whatever is to remain sacred, must be clothed in mystery.” But for Jabès it is also the question of Jewish survival.

The son of wealthy Egyptian Jews, Jabès was born in 1912 and grew up in the French-speaking community of Cairo. His language and interests have always been French. His earliest literary friendships were with Max Jacob, Paul Eluard, and René Char, and in the Forties and Fifties he published several small books which were later collected in Je bâtis ma demeure (1958). Up to that point, his reputation as a poet was solid, but because he lived outside France, he was not very well known there.

The Suez Crisis of 1956 changed everything for Jabès, both in his life and his work. Forced by Nasser’s regime to leave Egypt and resettle in France—consequently losing his home and all his possessions—he experienced for the first time the burden of being Jewish. Until then, his Jewishness had been nothing more than a cultural fact, one element of his life. But now that he had been made to suffer for no other reason than that he was a Jew, this cultural fact was transformed and became all-important.

Difficult years followed. Jabès took a job in Paris and was forced to do most of his writing on the metro to and from work. When, not long after his arrival, his collected poems were published by Gallimard, the book was not so much an announcement of things to come as a way of marking the boundaries between his new life and an irretrievable past. Jabès began studying Jewish texts—the Talmud, the Kabbala—and though this reading did not cause him to accept the religious precepts of Judaism, it did provide a way of affirming his ties with Jewish history and thought. More than the Torah, it was the writings and rabbinical commentaries of the Diaspora that moved Jabès, and he began to see in these books a strength particular to the Jews, one that translated itself into a mode of survival. In the long interval between exile and the coming of the Messiah, the people of God had become the people of the Book. For Jabès, this meant that the Book had taken on all the weight and importance of a homeland.

The Jewish world is based on written law, on a logic of words one cannot deny.

So the country of the Jews is on the scale of their world, because it is a book….

The Jew’s fatherland is a sacred text amid the commentaries it has given rise to….

At the core of The Book of Questions is a story—the separation of two young lovers, Sarah and Yukel, during the Nazi deportations. Yukel is a writer—described as the “witness”—who serves as Jabès’s alter ego, and whose words are often indistinguishable from his; Sarah is a young woman who is shipped to a concentration camp and returns insane. But the story is never really told in a traditional narrative way. Rather, it is alluded to, commented on, and now and then allowed to burst forth in the passionate and obsessive love letters exchanged between Sarah and Yukel, which seem to come from nowhere, like disembodied voices articulating what Jabès calls “the collective scream…the everlasting scream.”

Sarah: I wrote you. I write you. I wrote you. I write you. I take refuge in my words, the words my pen weeps. As long as I am speaking, as long as I am writing, my pain is less keen. I join with each syllable to the point of being but a body of consonants, a soul of vowels. Is it magic? I write his name, and it becomes the man I love….

And Yukel, toward the end of the book:

You could save me, Sarah.

Behind us, there was laughter still in a state of buds; before us, goodbyes which showed us the way. And suddenly, I saw you and felt that, helping you, I helped myself. Because you were too fragile to carry alone the weight of your yellow star. And I was too alone to stray from the herd.

You could save me, Sarah, resuscitate my childhood, give arms to my adolescence, make me a man….

I did not look for you, Sarah. I did look for you. You were going to save me. We had lost, you understand? I was going to save you. In you, everything testified that not all was lost.

And I read in you, through your dress and your skin, through your flesh and your blood. I read, Sarah, that you were mine through every word of our language, through all the wounds of our race. I read, as one reads the Bible, our history and the story which could only be yours and mine.

Advertisement

This story, which is the “central text” of the book, is submitted to extensive and elusive commentaries in Talmudic fashion. One of Jabès’s most original strokes is the invention of the imaginary rabbis who engage in these conversations and interpret the text with their sayings and poems. Their remarks, which most often refer to the problem of writing the book and the nature of the Word, are elliptical, metaphorical, and set in motion a beautiful and elaborate counterpoint with the rest of the work.’

“He is a Jew,” said Reb Tolba. “He is leaning against a wall, watching the clouds go by.”

“The Jew has no use for clouds,” replied Reb Jalé. “He is counting the steps between him and his life.”

Because the story of Sarah and Yukel is not fully told, because, as Jabès implies, it cannot be told, the commentaries are in some sense an investigation of a text that has not been written. Like the hidden God of classic Jewish theology, the text exists only by virtue of its absence.

“I know you, Lord, in the measure that I do not know you. For you are He who comes.”

—Reb Lod

The Book of Questions is a work composed entirely of fragments, of seemingly random pieces that Jabès manages to hold together by an uncanny sense of rhythm, proportion, and juxtaposition. Nothing really happens except the writing of the book itself—or rather, the attempt to write the book, a process that the reader is allowed to witness in all its hesitations and gropings. Like the narrator in Beckett’s The Unnamable, who is cursed by “the inability to speak [and] the inability to be silent,” Jabès’s narrative goes nowhere but around and around itself. As Maurice Blanchot has observed in his excellent essay on Jabès (in L’Amitié): “The writing…must be accomplished in the act of interrupting itself.” A typical page in The Book of Questions mirrors this sense of difficulty: isolated statements and paragraphs are separated by white spaces, then broken by parenthetical remarks, by italicized passages and italics within parentheses, so that the reader’s eye can never grow accustomed to a single, unbroken visual field. One reads the book by fits and starts—just as it was written.

At the same time, the book is carefully divided into four parts, “At the Threshold of the Book,” “And You Shall Be in the Book,” “The Book of the Absent,” and “The Book of the Living.” Jabès treats The Book of Questions as if it were a physical place, and once we cross its threshold we pass into a kind of enchanted realm, an imaginary world that has been held in suspended animation. As Sarah writes at one point: “I no longer know where I am. I know. I am nowhere. Here.” Mythical in its dimensions, the book for Jabès is a place where the past and the present meet and dissolve into each other. There seems nothing strange about the fact that ancient rabbis can converse with a contemporary writer, that images of stunning beauty can stand beside descriptions of the greatest devastation, or that the visionary and the commonplace can coexist on the same page. From the very beginning, when the reader encounters the writer at the threshold of the book, we know that we are entering a space unlike any other.

“What is going on behind this door?”

“A book is shedding its leaves.”

“What is the story of the book?”

“‘Becoming aware of a scream.”

“I saw rabbis go in.”

“They are privileged readers. They come in small groups to give us their comments.”

“Have they read the book?”

“They are reading it.”

“Did they happen by for the fun of it?”

“They foresaw the book. They are prepared to encounter it.”

“Do they know the characters?”

“They know our martyrs.”

“Where is the book set?”

“In the book.”

“Who are you?”

“I am the keeper of the house.”

“Where do you come from?”

“I have wandered….”

Although Jabès’s imagery and sources are for the most part derived from Judaism, The Book of Questions is not a Jewish work in the same way that one can speak of Paradise Lost as a Christian work. While Jabès is, to my knowledge, the first modern poet consciously to assimilate the forms and idiosyncracies of Jewish thought, his relationship to Jewish teachings is emotional and metaphorical rather than one of adherence. Jabès remains, above all else, a French poet. The Book of Questions came into being because Jabès found himself as a writer in the act of discovering himself as a Jew. By a startling leap of the imagination, he equates these two elements of himself and treats them as identical. Yukel says: “I talked to you about the difficulty of being Jewish, which is the same as the difficulty of writing. For Judaism and writing are but the same waiting, the same hope, the same wearing out.”

Similar in spirit to an idea expressed by Marina Tsvetaeva—“In this most Christian of worlds / all poets are Jews”—this is the central observation in Jabès’s work, the kernel from which everything else springs. To Jabès, nothing can be written about the Holocaust unless writing itself is first put into question. If language is to be pushed to the limit, then the writer must condemn himself to an exile of doubt, to a desert of uncertainty. What he must do, in effect, is create a poetics of absence.

When the yellow star was shining in the sky of the accursed, he wore the sky on his chest. The sky of youth with its wasp’s sting, and the sky with the armband of mourning.

He was seventeen. An age with wide margins.

And then one night, a little before day. And then one day, and then one night, and then nights, and days which were nights, the confrontation with death, the confrontation with the dawn and dusk of death, the confrontation with himself, with no one.

Although Wesleyan University Press is to be commended for making Jabès available to American readers, they have made an unfortunate mistake in publishing The Book of Questions as a work of “fiction.” It is no more a piece of fiction than Piers the Plowman or Blake’s Jerusalem. Difficult to classify, The Book of Questions would seem closer to the category of “poetry.” The distinction is important. For while Jabès writes for the most part in prose, both his sources and his tone are poetic, and his work must be seen in the light of its mythopoeic origins. The Book of Questions is not a novel; it is a visionary poem.

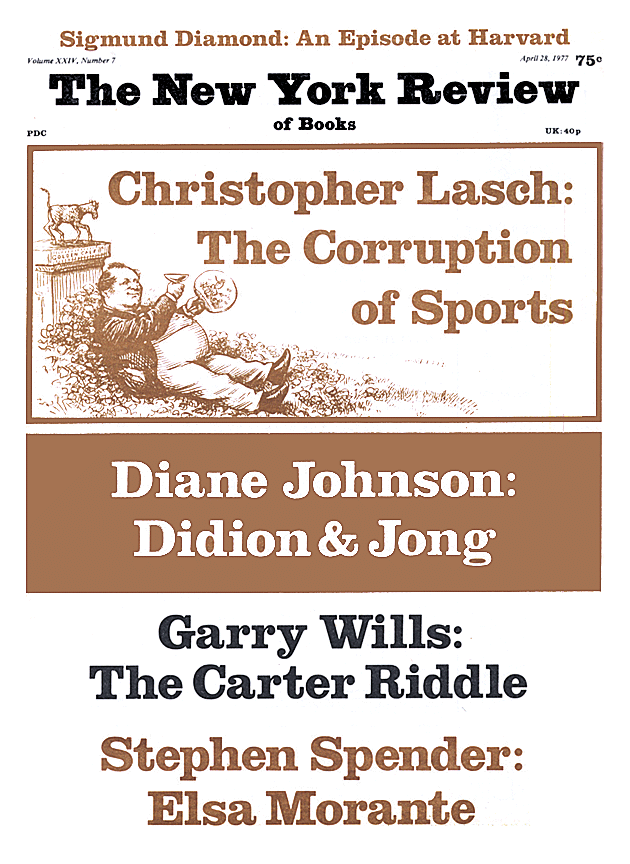

This Issue

April 28, 1977

-

*

Le Livre de Yukel (1964), Le Retour au Livre (1965), Yaël (1967), Elya (1969)—which has also appeared in a translation by Rosmarie Waldrop published by Tree Books—Aely (1972), (Et, ou le dernier livre) (1973), and Le Livre des Ressemblances (1976). ↩