Orville Schell’s deft reporting catches a Chinese yearning for American things and ways that many Americans will encounter in times to come. It is an aspect of Chinese life, however, that needs to be kept in a well-informed perspective, lest we mistake it for a wave of the future.

China’s speed of change puts a premium on the observer’s mental agility and historical memory. Thus the pragmatism espoused by Deng Xiaoping in recent years harks back not to Mao but to the two-year visit of John Dewey to lecture in China in 1919-1921 and to the reformist approach (“bit by bit, drop by drop”) then espoused by the Hu Shih wing of the May 4 movement. Hu Shih, Dewey’s student, translated for him and inveighed against ideological “isms” and the violent means they sanctioned. The Marxist-Leninist Ch’en Tu-hsiu wing of the May 4 movement did not succeed in founding the Chinese Communist Party until June 1921, just as Dewey was returning to America. By the 1940s violent revolution of course seemed essential to inaugurate the new order, but when Mao called for it again in his Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s things went too far. The reaction against it now in favor of gradual pragmatic reform happily puts China in better tune with the United States. The problems of modern growth that have us by the throat are threatening to strangle China too. We exchange delegations to consult about it. Consultation is possible because, at least so far as US-Chinese relations are concerned, neither the Chinese nor the Americans suffer at the moment from the fevers of ideological righteousness that have so fitfully accompanied our modernizations.

Fifteen years ago in 1966 we Americans were on our last ideological binge, typically as far off as possible in Vietnam, while the Chinese were having theirs more cheaply at home in Mao’s Cultural Revolution. These two fevers burned simultaneously (and damn near wrecked us both) for most of a decade, 1965-1973 for our crusade in Vietnam, 1966-1976 for Mao’s crusade in China. Were they connected? Undoubtedly.

Note first the intellectual limitations of our patriotic leaders on both sides. After the bitter and open Sino-Soviet split of 1960, American leaders who still believed in 1965 that the Soviets and Chinese were a monolithic juggernaut needed a mental examination. They can be forgiven for not knowing the record of Vietnam’s ancient hostility to Chinese control since none of us had ever heard of Vietnam until World War II. After the example of Japan’s, Russia’s, and even Korea’s modernization by foreign borrowing, Chinese leaders who proudly believed China could meet its modern problems in an antiforeign, anti-intellectual isolation, by rapidly reinventing the wheel and the steam engine while changing class structure through repeating Mao’s thoughts, also deserved to be tested for their grasp of reality. Mao had found his greatest conviction of reality, of course, in the hillside cavehouses of Yenan.

These intellectual limitations had greater effect because the leaders on both sides were prisoners of ideology. Both had found cohesion at home in the 1950s by teaching themselves to fear the menace of foreign “communism” and of foreign “imperialism,” respectively. They were cognate evils, each seen on the other side as a pervasive menace that must be met by a new birth of righteousness. American GIs bombing villages in Vietnam, Red Guards pillorying intellectuals in China, each nastiness sanctioned the other. Only practical common sense and our mutual disasters in Korea restrained each side from sending troops to meet on the ground in North Vietnam.

After Mao and LBJ had committed themselves to their respective crusades in the late 1960s and met frustration, the parallelism in China’s and the United States’s experience grew less distinct. No doubt the fall of President Nixon in 1975 and of the Gang of Four in 1976 shared some overtones. At any rate today in 1981 we seem for the moment less fevered on both sides, more at sea, only craving a return from somewhere of that ennobling and reassuring sense of righteousness that makes a national crusade possible.

Orville Schell reports on China’s transition from Maoist fervor gone astray under the Gang of Four to Deng’s pragmatism of the Four Modernizations. He was one of a small group of American student radicals privileged in 1975 to work in the fields at Mao’s national shrine to collective agriculture, the Dazhai (Ta-chai) Brigade in the loess country of Shansi province west of Peking. (Dazhai is now a Lourdes manqué, condemned as having been a fraud.) After Mao’s death in 1976 Schell has been back to Peking and Shanghai three times, running into disaffected Chinese who have talked more and more freely. Their talk makes him wonder, “What ever happened to Mao’s revolution?”

Advertisement

Instead of a consul general’s report balancing all the factors, he offers a series of impressions from personal contact: peasant children at Dazhai suddenly seduced into consumerism by a Polaroid camera; disco life and the most feasible of all consumerism, prostitution, at a Peking café; would-be Americanized youths riding mopeds in Shanghai; the charming daughter of an offical, who spent six years farming in Mongolia and four in a factory before getting into college; an old gentleman in Shanghai who once worked for a foreign firm and was jailed for it; and the new free market in Dairen. The question is how far such Chinese on the alienated urban fringe represent an infection among their countrymen whose consumerist hopes may lead to explosive frustration.

Among these vignettes from the PRC Schell interlards his journalist’s impressions of Deng’s visit to Washington, DC, Atlanta, Houston, and Los Angeles, where the American media showed our material gimmicks and crass consumerism for beaming back to China’s new TV network. Schell pictures a modernizing America, so free as to lack self-discipline, offering its cultural chaos to a proud but envious modernizing China that can’t afford to buy it and doesn’t want more than selected parts of it in any case.

Schell’s vignettes abound in symbolism. Deng’s patting a new yellow LTD as it comes off the Ford assembly line in Hapville, Georgia, signals his watching countrymen that it is “again permissible to aspire toward Western luxuries; again proper to exalt technocrats.” Schell sees a breakthrough at the rodeo in Simonton, Texas: as celebrities, Deng and his entourage have been besieged by Americans wanting things from them. But the Texans at the rodeo, “instead of trying to ingratiate themselves like everyone else,” are simply their “normal boisterous and hospitable selves” with no designs at all. It makes for mutual acceptance which can include the obvious point that our two countries face a host of common problems on which we may be able to help each other.

The acceptance of ever more extensive American contact is, however, a dream that seems to have already faded in China. The gross incongruities in styles of life point up the need to go slow in our getting together. Neither Orville Schell nor any of his Chinese friends can see how the Americanization of China can go on unchecked. His friends prefer to escape China and come to America. Personal automobiles cannot become a necessary tool of life among a billion Chinese. Nor can they afford the conceits that some of us cherish, for example that a fetus under five months is already a person, or that handguns are commodities to buy and sell in the marketplace like any other. American profligacy is beyond their material capacity. Meanwhile our type of modern legality and litigation have not yet got very far in taking precedence over China’s traditional morality.

Deng and his successors must try to keep the post-revolutionary growth damped down to the level of a controlled reaction. Sociological research, for example, is part of the modernization of science but that does not mean that American sociologists can have the run of the Chinese countryside. Everything about America has side effects likely to raise the level of hope and frustration for individual Chinese. Since the PRC’s billion people is the world’s greatest pool of talent, too many American stimuli can touch off strains that may lead to explosions. We are too easily aggressive. Rather than let the Harlem Globetrotters recruit in China, we must wait for the Chinese basketball administration to field its own team of eight-foot ball-handlers.

Let us not forget that China has been until very recently a dominant, majority civilization in its own region. It has therefore been slow to take on the task of being a developing minority society in today’s international world. America as a society of immigrants and developers may keep on trying to expand its relations with China. But China’s leaders are constantly tempted, as Mao was, to keep the outside world at arm’s length. This idea is enforced upon them by the combined pride and poverty of a billion people with a powerful sense of identity and of material needs.

The alienation from Mao’s post-1957 thought which Schell finds in his marginal people seems also widespread among Chinese intellectuals, beginning with the many victims of the Cultural Revolution—that hysterical process by which the later revolutionaries tried to destroy the earlier revolutionaries. Mao’s leadership in thus bombarding the party headquarters and destroying the party itself casts him in the role of tyrant. But this creates a major dilemma of legitimacy for the new team under Deng. When Stalin was exposed as a tyrant, the Soviets could still bow to Lenin as the founding father. But Mao is for China’s revolution both founding father and, as now exposed, tyrant. The horror stories of destruction of things, people, and values during the Cultural Revolution accumulate day by day. The Deng regime now confronts the problem of how to avoid throwing out Mao’s entire legacy along with the Gang of Four.

Advertisement

This they will not do nor would it be justified. But their need to limit the Americanizing aspects of China’s modernization is plainly necessary not only for simple reasons of cost but also because of that more subtle xenophobic heritage expressed in Schell’s title “Watch Out for the Foreign Guests!” In short, pragmatism has its limits. It cannot be an all-out approach to the US.

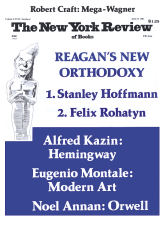

This Issue

April 16, 1981