Assault, rape, brutal domination, exquisite torture—such activities figure largely in what might be called the higher pornography (L’Histoire d’O, for instance), where they are the expected lot of the heroine-victim. But there is another kind of novel (perhaps not unrelated) in which the palpably aggressive component is directed not so much at a character as at the reader. Here the intention seems to be to enslave the reader’s imagination, to subdue it to every twist, extravagance, or ramification of the writer’s imagination. A number of brilliantly executed contemporary works—Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, Barth’s Giles Goat-Boy, Gaddis’s JR—come to mind. Wooing or seduction plays no part in the strategy of such novels; as Ogden Nash wrote somewhere, seduction is for sissies, a he-man likes his rape. The inflatio ad absurdum of the species is no doubt Ancient Evenings. Often there is a paranoid coloration to fiction of this kind, as if the impulse to total control reflects the fear of such control from outside—by a network of omniscient spies, perhaps, or some universal “system” from which there is no escape.

Robert Coover’s The Public Burning (1977) is a good example of a novel in the bullwhip-and-manacles mode. Prolix, dazzling in its reproduction of American speech patterns, wildly and often farcically inventive, it is also remorseless in its determination to hold the reader captive in a situation that includes not only the prolonged agony of Ethel Rosenberg but the sodomization of Richard Nixon by that raunchy, goat-bearded old windbag, Uncle Sam. Though Coover’s new novel lacks the political savagery of its predecessor, Gerald’s Party is equally relentless in its pursuit of outrage and its attempt to reduce the reader to a condition of helpless and exhausted voyeurism. It is also a work of considerable comic vitality, full of inspired mimicry and parody, gleeful in its unabashed sadism.

“None of us noticed the body at first”—so the novel begins. The party at Gerald’s house has been under way for hours, though only one guest has so far passed out. Gerald is busy refilling drinks and his wife (who is never given a name) is busy supplying food—activities which they will both conscientiously pursue throughout the ensuing chaos. The victim, Ros, has been lying on the living-room floor while the guests mill around her obliviously. The host has turned his attention to a lovely woman, Alison, who has challenged him by saying, “You know, I’ll bet you’re the sort of man who used to believe, once upon a time, that every cunt in the world was somehow miraculously different.”

The discovery of poor Ros is indeed sensational, but it by no means totally preoccupies either Gerald or his guests:

Ros’s front was bathed with blood—indeed it was still fountaining from a hole between her breasts, soaking her silvery frock, puddling the carpet. I could hardly believe my eyes. I had forgotten that blood was that red, a primary red like the red in children’s paintboxes, brilliant and alive, yet stagy, cosmetic. Her eyes were open, staring vacantly, and blood was trickling from the corners of her mouth….

Alison’s hip had slid into the hollow above my thigh, as though, having pushed past me for a moment to see, she was trying now to pull back and hide inside me. It felt good there, her hip, but I was wondering: How has it got so hot in here? Who turned up the lights?

The blood keeps coming; sooner or later, nearly everyone at the party is imbrued.

“Your whole house looks like it’s suffering from violent nosebleed, Ger.”

“Well it just goes to show,” I said vaguely.

Coover’s technique of constant distraction and interruption—ranging from broken-off conversations to fellatio interrupta—creates a jerky, strobe-lit effect that is augmented by the ceaseless coming and going of the huge cast of guests—Chuck, Naomi, Sally Ann, Soapie, Tania, Dickie, etc. The reader is bombarded with fragments of scenes, with snatches of disembodied talk, with dizzying non sequiturs. The police, led by the philosophical Inspector Pardew, arrive and proceed to commit various indignities on Ros’s body in the name of scientific investigation, but we are allowed to see this action only in sporadic glimpses—for meanwhile we have been crowded into an upstairs bathroom where Naomi, who has copiously beshat herself out of sheer terror, is having her bottom wiped first by Dickie and then by Gerald (who also applies baby oil), while Tania is attempting to rinse out her bloodstained dress in the bathtub (in which she later drowns). Or else we are in the kitchen, where Gerald’s wife produces an unending supply of turkeys, pizzas, moussaka, egg rolls, canapés, dips, etc., from her cornucopialike refrigerator and oven. Or else we are in the back yard, which multitudes of urinating guests have turned into a mud puddle. Or in the sewing room, crowded with couples copulating in the dark. Still later, we return to the wreckage-strewn living room, where an avant-garde director is improvising a play that attempts to blur the distinction between fantasy and reality—with Ros’s body, needless to say, as a crucial prop.

Advertisement

Through the nightmarish din and flickering lights of the novel certain characters emerge with a kind of Dickensian clarity of outline. One is Gerald’s wife, who moves imperturbably, if sometimes a bit wearily, through the novel, not only dishing out food but cleaning up the awful recurrent messes, introducing newcomers, and helping with the various crises as they occur. “I do wish people wouldn’t use guns in the house,” she complains mildly after a guest has been shot. “Somehow parties don’t seem as much fun as they used to,” says this model of platitudinous domesticity near the end of the book—just before she surprises the reader by engaging Gerald in a sex scene as pornographically vivid as any of the others depicted in this cheerfully lubricious novel.

Then there is Inspector Pardew, who mouths such pronouncements as

Murder, like laughter, is a muscular solution of conflict, biologically substantial and inevitable, a psychologically imperative and, in the case of murder, death-dealing act that must be related to the total ontological reality!

Just before the revelation (if it is that) of Ros’s murderer, the inspector ruminates, pipe in hand, on crime as a “form of life depreciation.” I shall quote him at length not only to illustrate his mode of discourse but to show the grotesque lengths to which Coover’s imagination can, when properly fired, impel him:

“I was reminded,” he said…, “of a curious case I had some years ago in which the murderer, as it turned out, was an unborn fetus. The victim was its putative father, who in a drunken rage had struck the pregnant woman several times in the stomach. The fetus used the only weapon at its command: false labor. It was a wintry night, the man was heavily inebriated, there was a terrible accident on the way to the hospital. The woman, who survived for a time, spoke of maddening pains en route, and it seems likely she grabbed the steering wheel in her delirium or lashed out with her foot against the accelerator. Was the fetus attacking its assailant or its host? This was perhaps a subtlety which, in its circumstances, escaped it. Certainly it achieved its ends, and though it could be argued that it had acted in self-defense, it seemed obvious to me that the true motive, as so often, was revenge.” He paused to let that sink in…. “The strawberries are starting to go soft,” my wife whispered. “In any event we’ll never know. Prosecution was impossible because the fetus—a hairlip—was stillborn. But the point—“

A kind of maniacal laughter rings through Gerald’s Party. Middle American rituals of conviviality, the pretensions of home-grown theatrical groups, the mangled ethos of the sexual revolution, the conventions of pornographic writing and of the detective novel—all are fed into Coover’s satanic mill. Coover, with his attuned ear for blather and eye for the unconscious buffoonery of our times, can be wonderfully funny. Yet Gerald’s Party is a punishing book. It never lets up. Like The Public Burning before it, the novel goes on too long, burdening the reader with a sensory overload from which there is no respite. If Gerald’s Party were half its length, it would be, I think, a small masterpiece of comic outrageousness. But as things stand, nothing depicted in the book is quite so perverse as Coover’s insistence on benumbing us—his reader-victim—with a plethora of repeated effects. I enjoyed much of Gerald’s Party, but well before the end I was ready to reach for the nearest Trollope.

By contrast, The Sportswriter, which is Richard Ford’s third novel, is a remarkably gentle and meditative book which belies the suggestion of hearty extroversion contained in its title. Rather the book steeps us, almost moment by moment, in the consciousness of its central character during three crowded days that mark a somewhat inconclusive shift in the direction of his life. What happens during that time is amplified by a series of extended flashbacks that have a direct bearing on Frank Bascombe’s present condition, which might be described as that of a man more badly wounded than he cares to admit.

Frank, who tells his own story, is a divorced man in his late thirties, a well-paid writer for a national sports magazine who was once a “real” writer of literary short stories and an aborted novel. “My life over these twelve years has not been and isn’t now a bad one at all,” he tells us at the start. “In most ways it’s been great.” Just how great it’s been—and is—forms a question that we are implicitly asked to consider as we track Frank over the course of the Easter weekend.

Advertisement

The action begins at dawn on Good Friday when Frank meets his ex-wife (referred to throughout merely as X) for a little ceremony of remembrance at the grave of their son, Ralph, who had died four years earlier of Reye’s syndrome. It is Ralph’s birthday—the boy would now be thirteen if he had lived. A muted, intermittently painful scene takes place between the two; they question each other about their present lives and intentions and they express, in various ways, their grief over Ralph. Both have stayed on since their divorce in the town of Haddam, New Jersey, where the younger children live with X. Just as the bells of St. Leo the Great are chiming six o’clock, they part. X

begins making her way quickly out through the tombstones, her head up toward the white sky, her hands deep in her pockets like any midwestern girl who’s run out of luck for the moment but will soon be back as good as new.

Frank has the feeling that he won’t see her again for a long time—“that something is over and something begun, though I cannot tell you for the life of me what those somethings might be.” (He in fact sees her several more times during the weekend.)

What follows is not in any sense a plotted novel with a rising action and a buildup of suspense. Instead we are given a series of detailed, vividly written episodes that succeed one another casually, almost haphazardly. One of these takes place outside of Detroit, where Frank (accompanied by his current girlfriend, Vicki) goes in order to interview a famous pro football player now crippled and confined to a wheelchair. Another occurs on Saturday night, when Frank, returning late to Haddam, finds an acquaintance named Walter waiting for him at his house. Walter, whom Frank has met through the Divorced Men’s Club, is distraught over an unexpected homosexual incident with a married man and seeks Frank’s acceptance and reassurance. Still another—an extended set piece really—involves a trip to the Jersey shore, where Frank and Vicki have Easter dinner with Vicki’s family.

These and other episodes are expertly rendered, but our chief interest throughout is in Frank’s response to them. Ford has achieved, I think, a triumph in his characterization of Frank Bascombe, a decent man, kindly and always eager to see the hopeful side of things. As he moves from encounter to encounter, he wants to proclaim the goodness of life but is often bewildered or hurt by what he actually experiences. He is immensely accepting of people and the myriad ways in which they live. Walter’s confession doesn’t faze Frank, though in general he dreads confessions; when Walter, misconstruing Frank’s tolerance, suddenly kisses him on the cheek, Frank is upset (“I would kiss a camel rather than have Walter kiss me on the cheek again”) but has no wish to react in a two-fisted way—he merely tells Walter to go home.

Frank is subject to prolonged states of dreaminess—a condition that became acute before his marriage ended and prevented him from taking steps to forestall a divorce that neither he nor X really wanted. “My son had died,” he says, “but I am unwilling to say that was the cause, or that anything is ever the sole cause of anything else. I know that you can dream your way through an otherwise fine life, and never wake up, which is what I almost did. I believe I have…nearly put dreaminess behind me, though there is a resolute sadness between X and me that our marriage is over, a sadness that does not feel sad.” That last phrase sums up what we come to perceive as Frank’s estrangement from his true feelings, of which the dreaminess is a symptom. He pretends to himself that he has “faced down” his grief over Ralph and his regret over his divorce. But of course these are the two very things that cause him to bleed—quietly and internally—throughout the book.

There are plenty of sad lives all around Frank. Walter is an example. So is the crippled football player, Herb Wallagher, about whom Frank hoped to write an “inspirational” article but who turns out to be not only embittered but more than a little crazy. Yet the emotional tone of The Sportswriter is anything but depressive. One of the chief pleasures of reading the novel comes from its sense of lively absorption in the varied details of contemporary American life that it conveys. Frank’s embrace of these details—including the most banal—reaches beyond acceptance to something approaching active celebration. Drive-ins, bars, airports, a glitzy hotel room in Detroit, New Jersey housing developments, even the hodgepodge landscape of New Jersey itself—all of these receive Frank’s enraptured attention. He relishes the lives of lower-middle-class people without even a hint of condescension; not only Vicki Arcenault, the feisty, literal-minded hospital nurse who is his girl-friend, but her father Wade, who collects tolls on the New Jersey Turnpike, and her stepmother Lynette, and her brother Cade are all recipients of his sympathetic and enlivening interest. The household of the Arcenaults on a man-made peninsula called Sherri-Lyn Woods is lovingly evoked, right down to the meaty smell of overcooked lamb from the kitchen (“Hope you like your lamb well, well, well done, Franky,” says Lynette. “That’s the way Wade Arcenault likes his.”) The fact that Wade has restored a huge, black tailfinned 1950s Chrysler in the basement of his house fills Frank with delight.

Yet this acceptance is not sentimentalized. Here is Frank’s account of Cade Arcenault:

Cade comes pushing through the front door. He has been out back tying down a tarp on his Boston Whaler, and when I shake his hand it is rock-fleshed and chilled. Cade is twenty-five, a boat mechanic in nearby Toms River, and a mauler of a fellow in a white T-shirt and jeans. He is, Vicki has told me, on the “wait list” for the State Police Academy and has already developed a flat-eyed, officer’s uninterest for the peculiarities of his fellow man.

And here, from the final pages of the novel, is his description of some newly discovered relatives in Florida:

Buster Bascombe is a retired railroad brakeman with a serious heart problem that could take him any hour of the day or night. And Empress, his wife, is a pixyish little right-winger who reads books like Masters of Deceit and believes we need to re-establish the gold standard, quit paying our taxes, abandon Yalta and the UN, and who smokes Camels a mile a minute and sells a little real estate on the side (though she is not as bad as those people often seem). Both are ex-alcoholics, and still manage to believe in most of the principles I do.

As these quotations suggest, Ford has fashioned a relaxed, colloquial style for Frank’s revelation of himself and the world around him, a style with much of the breeziness but few of the clichés that we associate with sports writing. It moves easily from description to commentary and merges seamlessly with passages of dialogue that characterize the speakers in all their variety of social and regional background.

One wonders however about the thematic significance of the Easter weekend. Despite the recurrent ringing of church bells, the possible allusion to Judas in Walter’s kiss, and the presence of a near-life-sized figure of the crucified Jesus on the Arcenaults’ lawn, I doubt that Ford intends us to seek anything allegorical in the Christian symbols. Frank, though a man of sorrows in certain respects, is hardly a Christ figure himself. Rather, he is distinctly a post-Christian man of good will trying to find his way in a world bereft of the certainties of its religious past. He hears, but cannot respond to, the summoning of distant bells.

The Sportswriter is not a “big” novel. It is slow-paced and, like its protagonist, lacks a clear sense of direction; it arrives nowhere, so to speak. The book is, instead, a reflective work that invites reflection, a novel that charms us with the freshness of its vision and touches us with the perplexities of a “lost” narrator who for once is neither a drunkard nor a nihilist but a wistful, hopeful man adrift in his own humanity.

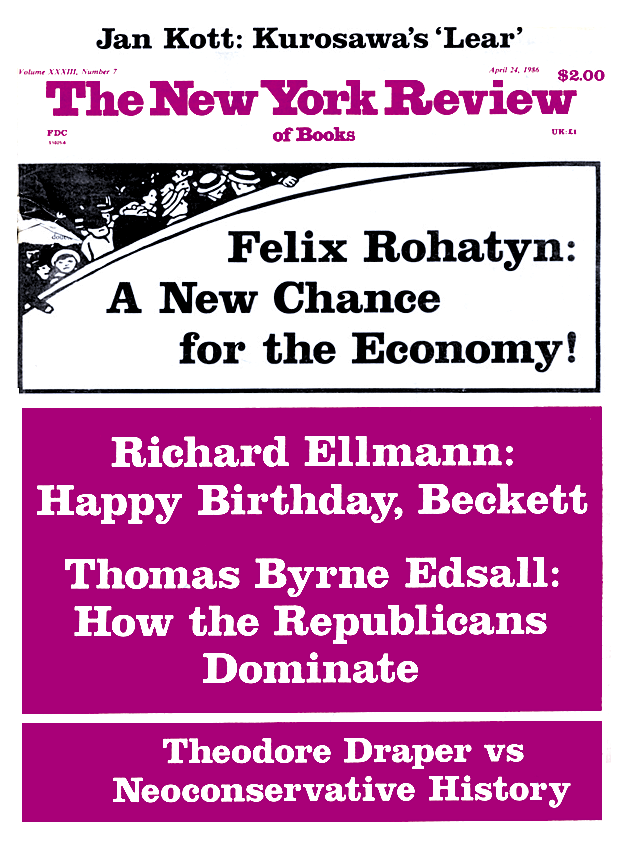

This Issue

April 24, 1986