1.

Biblical style in English carries on it the palpable impress of the Protestant martyr William Tyndale (1494–1536). Strangled and then burned, with the approval of Henry VIII, for publishing an English version of the New Testament despite the opposition of the Church, Tyndale did not have time to complete his translation of the Christian Old Testament, as he had the New. All English Bibles after Tyndale manifest his continued presence, and not only because he was the crucial forerunner. It is not excessive to judge that, after Shakespeare and Chaucer, Tyndale may be the greatest writer in the language. We go about daily—many of us—unknowingly repeating sentences, phrases, and words invented as much by Tyndale as by Shakespeare. The Geneva Bible (1560) was Shakespeare’s resource from Shylock and Falstaff in 1596 onward, and continued to be favored by John Milton. For most of the English, it yielded to the Authorized Version or King James Bible (1611), which maintains its hold on the English-speaking world almost until this moment. Both the Geneva and King James Bibles follow Tyndale wherever they can, so that he remains, with Shakespeare, a comprehensive influence upon us.

David Daniell, Tyndale’s biographer,1 has written persuasively concerning the translator’s effect on Shakespeare’s various styles in the later tragedies. Tyndale is the master, when he chooses to be, of a style of plain speaking: short pronouncements held together by parataxis, with no subordinate clauses. “Parataxis” is a word I employ reluctantly (it makes my students unhappy) but there is no good substitute for it, whether in discussing Tyndale and Shakespeare, or Walt Whitman and Ezra Pound. The word is from the Greek for “placing side by side” and emphasizes a way of juxtaposing phrases that is central to the style of biblical Hebrew, with its syntactically parallel clauses, which tend also to possess a parallelism of meaning. Here is a well-known example by Ezra Pound:

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough.

—“In a Station of the Metro”

Shakespeare’s grand gift, for phrasing so memorably that we find the language inevitable, is very nearly matched by Tyndale’s outspoken directness of address, what Daniell calls his “everyday manner,” and his aversion to Latinity. Getting Tyndale out of my head seems to me impossible: “Let there be light, and there was light”; “In him we live and move and have our being”; “Am I my brother’s keeper?”; “The signs of the times”; “The spirit is willing but the flesh is weak”; “For you have wrestled with gods and men and have prevailed”; and scores of others. Whether I immerse myself in the Geneva or the King James Bible, Tyndale’s genius (though not his Protestant zeal) enriches me.

As a Jewish reader, I tend to be aware that these are Christian Bibles, and therefore alien to me spiritually though not as language and as imaginative experience. Whatever questionings about Robert Alter’s versions of Tanakh, the Hebrew Bible, I may venture in this essay-review, they take place within an aura of appreciation and gratitude, for quite uniquely his vast, ongoing project is giving us a Jewish Bible in American English. His Book of Psalms joins his Five Books of Moses2 and The David Story3 as a considerable achievement. I hope to live to read his Prophets and Writings, including Job, Koheleth, and the Song of Songs. For many years now I have fretted about the relative lack of an American Jewish cultural achievement, when compared to the wonderful body of work that came out of German-speaking Jewry before the Holocaust. Among indubitable labors of lasting value, Alter’s enterprise already occupies an eminent place. Like any strong creator, Alter competes with the King James Bible, which he knows finally means with William Tyndale, or where Tyndale was cut off by martyrdom, with other English Renaissance translators. For the Psalms, that is Anthony Gilbey, the best Hebraist among the translators of the Geneva Bible.

2.

The Book of Psalms, particularly in the King James version, is the best-known part of the Hebrew Bible (or Christian Old Testament, if you will). Psalm 23, in its King James text, indubitably is recognized even by people who have never read the Bible: “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.” Though ascribed to King David, whose historical existence is as uncertain as that of his supposed descendant Jesus, the Psalms are no more David’s than the Song of Songs is Solomon’s or the Five Books are by Moses. There is not much in the Bible, whether Hebrew or Christian, that can withstand historical skepticism. The Exodus is as mythical as the Creation or the Crucifixion. In the United States at this time, religion is politicized, and no one running for office dares to be other than outwardly pious. In this respect the abyss between the United States and Western Europe (barring Ireland) is now absolute.

Advertisement

Scholars agree that the Psalms are an anthology, or a bundle of anthologies, composed over six centuries. Many of the songs were written for use in the Jerusalem Temple, though later Psalms clearly have been created for other purposes. We are likely to characterize all 150 Psalms as “religious poetry,” but that is disputable. Six centuries of a poetic tradition, analogous to English poetry from Chaucer through Yeats, necessarily develop what we could now regard as aesthetic competition. Even with the much later esoteric tradition of Kabbalah, it helps to consider the literary motives of kabbalistic authors, who frequently have a combative relation to one another.

Alter notes the debts of some Psalms to Canaanite mythology, which was polytheistic. Between 996 and 457 BCE and beyond—the approximate period in which most of them were composed—is an ocean of time, taking one from the Judges past the return from Babylon, and ideas of God underwent many metamorphoses. The Authorized Version smooths out differences, but the God the Psalms address has varied guises that Alter’s closeness to the Hebrew text is better able to reveal. Theologically, Tyndale and his progeny were Calvinists, and Yahweh is not a Presbyterian. Though Alter’s audacity in aesthetically challenging Tyndale, the Geneva Bible, and the King James version is admirable, it leads to a kind of honorable defeat. But how refreshing it is to read the Psalms in their abrupt rhythms, cleared of irrelevant Protestant “salvation history.” There is no Jewish theology before the Hellenistic Philo of Alexandria (20 BCE–50 CE). Theology, a Greek idea and term, is alien to the Hebrew Bible. When I encounter discussions of “the theology of the Old Testament” I wander off, but Alter holds me to his darkly economical texts.

Hebrew tradition always refers to the Book of Psalms by a noun meaning “praises.” On their surface, the Psalms praise Yahweh (under various names) and even the frequent appeals for his help abound with overtones of gratitude. From childhood through old age I have been made uncomfortable by a God who demands sacrifices that are also thanksgivings. Post-Holocaust, this will not work for many among us, and I frequently retreat from the Psalms to the poetry of Paul Celan, which has a difficult rightness, and does not seek to praise what no longer can be praised. Alter, highly aware of Celan, sometimes is able to suggest modulations in the perpetual hail of praise that rains down in the Psalms.

3.

The Psalms give us a Yahweh (Alter avoids the numinous name) who himself is a living labyrinth of parallelisms and parataxis. Tradition affirms that Yahweh gave us Hebrew; did Hebrew syntax give us Yahweh? The Hebrew language, Yahweh, and his book, Tanakh, in effect are the same. Alter’s The Book of Psalms, like his Five Books of Moses and his David Story, shows this more plainly than do Tyndale and his Calvinist brethren and successors.

Alter, indomitable in his quest, is the Captain Ahab of biblical translation. His white whale, unslayable, would be a Hebrew Bible in American English free of Protestant colorings. One of Alter’s virtues is to make me wonder whether ancient Hebrew thinking is at all still available to us. Perhaps only Shakespeare rethought everything through for himself; the Psalms do not, though we scarcely can pick out what may once have been original in them. Was it a making of praise, gratitude, supplication, even despair into modes of thinking? Angus Fletcher and the late A.D. Nuttall, both in Wittgenstein’s wake, have given us useful conjectures about how Shakespeare thought. Biblical thinking is mostly opaque to our understanding, and the Psalms particularly puzzle me, since many of them are and yet are not prayers. Human analogues may aid in apprehending the Psalms. Anyone called upon too frequently to endorse books and students learns that praise can be both a subtle kind of thinking or rethinking and also a treacherous one.

The God of the Psalms has comforted multitudes, whether in the valley of decision or in the valley of the shadow of death. He does not comfort me, because I do not know how to think in a realm of gratitude. When I returned to life this late August, after nine days in a hospital recovering from a syncope, I went back to reading Shakespeare instead of the Bible. There is no separation between life and literature in Shakespeare. Because of American politics and our crusading zeal abroad, one needs to keep the Bible apart from the way we live now.

4.

The Psalms are a bolder and more challenging field for Alter’s literary energies and knowledge to explore than either the Five Books or the David saga, because ancient Hebrew poetry seems untranslatable into contemporary American English. At the least, Alter surpasses anyone else in this hazardous experiment. His central burden is that he himself is a better narrative writer than a poet or prose poet, and here his contest is largely with the King James Psalms. They are familiar, comforting or daunting, and almost continuously eloquent. Yet there is little that is Hebraic about them; they have become marvelous Christian prose poems. I am more than sympathetic to the unspoken aspect of Alter’s quest: How are America’s Jews to take back what should be their own?

Advertisement

Alter, a critic of great sophistication, does not allow himself to express any uneasiness with the Christian appropriation of the Bible. I prefer to be rougher about this two-thousand-year-old theft. The Old Testament is a captive work dragged along in the triumphal wake of Christianity. Tanakh, the Jewish Bible, is the Original Testament; the New Testament actually is the Belated Testament. I wince when my Jewish students speak of the Old Testament. Yet, there are perhaps 13 million self-identified Jews now alive, and (I believe) some 1.6 billion ostensible Christians. The arithmetic is beyond me, but if God is with the big battalions, then he would seem to have forsaken his People of the Book. All honor yet again to Alter for his ambition in giving us back the Book.

Yet in literary terms, Alter’s contest in this translation is even more difficult than it was in his Five Books of Moses or his David Story. Tyndale was a far stronger writer than Anthony Gilbey and his Geneva Bible colleagues, or than Gilbey’s revisionists in the King James. Gilbey too was an extraordinary prose poet; but however good his Hebrew may have been, his intentions were doctrinal rather than aesthetic. The art of biblical poetry has long been one of Alter’s concerns, and he is determined to bring the syntax and rhythms of the Psalms into English. He brilliantly succeeds but nothing is got for nothing, and reading through the 150 Psalms first in Alter and then in the King James will not show that he is a victor in the contest with Gilbey and the King James revisionists. The abruptness of the Hebrew, its powerful economy, is transferred to us, but the results sometimes are jagged.

Here I intend to allow other readers to decide for themselves; and start now with Tyndale, who rendered Psalm 18, embedded in 2 Samuel 22, and parts of Psalms 105, 96, and 106, included in 1 Chronicles 16. Here is the opening of Tyndale’s Psalm 18:

And he said: The Lord is my rock, my castle and my deliverer. God is my strength, and in him will I trust: my shield and the horn that defendeth me: mine high hold and refuge: O my Saviour, save me from wrong.

I will praise and call on the Lord, and so shall be saved from mine enemies. For the waves of death have closed me about, and the floods of Belial have feared me. The cords of hell have compassed me about, and the snares of death have overtaken me. In my tribulation I called to the Lord, and cried to my God. And he heard my voice out of his temple, and my cry entered into his ears. And the earth trembled and quoke, and the foundations of heaven moved and shook, because he was angry.

Smoke went up out of his nostrils, and consuming fire out of his mouth, that coals were kindled of him. And he bowed heaven and came down, and darkness underneath his feet. And he rode upon Cherub and flew: and appeared upon the wings of the wind. And he made darkness a tabernacle round about him, with water gathered together in thick clouds. Of the brightness, that was before him, coals were set on fire.

The Lord thundered from heaven, and the Most High put out his voice. And he shot arrows and scattered them, and hurled lightning and turmoiled them. And the bottom of the sea appeared, and the foundations of the world were seen, by the reason of the rebuking of the Lord, and through the blasting of the breath of his nostrils. He sent from on high and fetched me, and plucked me out of mighty waters.

Here is Alter:

And he said:

I am impassioned of

You, LORD, my

strength!

The LORD is my crag and my

bastion,

and my deliverer, my

God, my rock where

I shelter, my shield

and the horn of my rescue, my fortress.

Praised I called the LORD

and from my enemies

I was rescued.

The cords of death wrapped

round me,

and the torrents of

perdition dismayed

me.

The cords of Sheol encircled me,

the traps of death

sprung upon me.

In my strait I called to the LORD,

to my God I cried out.

He heard from His palace my

voice,

and my outcry before

Him came to His

ears.

The earth heaved and shuddered,

the mountains’

foundations were

shaken.

They heaved, for smoke rose from

His nostrils

and fire from His

mouth consumed,

coals blazed up

around Him.

He tilted the heavens, came down,

dense mist beneath His

feet.

He mounted a cherub and flew,

and he soared on the

wings of the wind.

He set darkness His hiding-place

round Him,

His abode water-

massing, the clouds

of the skies.

From the brilliance before Him

His clouds moved ahead—

hail and fiery coals.

The LORD thundered from on high.

Elyon sent forth His

voice—hail and fiery coals.

He let loose His arrows,

and scattered them,

lightning bolts shot,

and He panicked

them.

The channels of water were

exposed,

and the world’s

foundations laid bare

From the LORD’s roaring,

from the blast of Your

nostril’s breath.

He reached from on high and took

me,

pulled me out of the

many waters.

Traditionally regarded as David’s victory ode, this is powerful in both versions, yet Tyndale takes the palm, not of course for accuracy but for preternatural force and eloquence. This may or may not be Yahweh, but certainly he is John Calvin’s ferocious God. Alter, highly conscious of the archaic, Canaanite elements, is careful to preserve them, but Tyndale writes like a possessed man, overcome by Jehovah’s power (I change God’s name because Jehovah was Tyndale’s own coinage, founded upon a spelling error). The King James softens Tyndale’s intensity in Psalm 18, wary of his burning Calvinism.

In an odd paradox, Alter’s book has no competitors, for no one else works so close to the Hebrew, and because the Psalms have drawn so many verse translations, his rivals include poets as gifted as Thomas Campion, Richard Crashaw, Thomas Carew, and John Milton (whom Alter commends). But only scholars now read them, so I here juxtapose the King James Authorized Version of Psalm 137 with Alter’s translation:

By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion.

We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof.

For there they that carried us away captive required of us a song; and they that wasted us required of us mirth, saying, Sing us one of the songs of Zion.

How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?

If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning.

If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth; if I prefer not Jerusalem above my chief joy.

Alter writes:

By Babylon’s streams,

there we sat, oh we wept,

when we recalled Zion.

On the poplars there

we hung up our lyres.

For there our captors had asked of us

words of song,

and our plunderers—rejoicing:

“Sing us from Zion’s songs.”

How can we sing a song of the LORD

on foreign soil?

Should I forget you, Jerusalem,

may my right hand wither.

May my tongue cleave to my palate

if I do not recall you,

if I do not set Jerusalem

above my chief joy.

Here Alter is gallantly defeated, but then so were Campion, Crashaw, and the others. Alter’s commentary validly defends his diction, but the cadences of the Authorized Version are beyond argument. Who would not choose: “How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land? If I forget thee, O Jerusalem”? Alter offers: “How can we sing a song of the LORD/on foreign soil?” The phrasing of 1611 is a miracle of style, testifying to the Age of Shakespeare. Alter, four centuries belated, is an authentic scholarly translator, but touches his limits here. I give the last word to the poet-critic John Hollander:

The verse of the Hebrew Bible is strange; the meter in Psalms and Proverbs perplexes.

It is not a matter of number, no counting of beats or syllables.

Its song is a music of matching, its rhythm a kind of paralleling.

One half-line makes an assertion; the other part paraphrases it; sometimes a third part will vary it.

An abstract statement meets with its example, yes, the way a wind runs through the tree’s moving leaves.

One river’s water is heard on another’s shore; so did this Hebrew verse form carry across into English.4

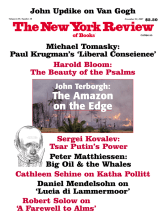

This Issue

November 22, 2007

-

1

David Daniell, William Tyndale: A Biography (Yale University Press, 1994). ↩

-

2

Norton, 2004; reviewed in these pages by Frank Kermode, October 20, 2005. ↩

-

3

Norton, 1999. ↩

-

4

John Hollander, Rhyme’s Reason: A Guide to English Verse (Yale University Press, third edition, 2001), p. 26. ↩