The murder of Daniel Malakov took only a few seconds to unfold. Malakov, a thirty-four-year-old orthodontist, was shot three times at close range on October 28, 2007, as he stood with his four-year-old daughter Michelle near the entrance to a playground in Forest Hills, Queens. He was there to meet his estranged wife, Mazoltuv Borukhova, a physician, to hand over Michelle—of whom Malakov had been given custody three weeks earlier—for an all-day visit with her mother. The gunman fled. Malakov died in hospital after an unsuccessful attempt by his wife to administer CPR on the pavement in the wake of the shooting. Michelle, after some initial bureaucratic confusion, was entrusted to members of Malakov’s family.

In November the gunman was identified as Mikhail Mallayev, a fifty-year-old resident of Chamblee, Georgia, and a relative of Borukhova’s by marriage; in February Borukhova was arrested and charged with hiring Mallayev to kill her husband. The case attracted considerable attention, not least because Malakov, Borukhova, and Mallayev all belonged to the tightly knit and, to the public, little-known Bukharan Jewish community, originating in Uzbekistan and now clustered in Forest Hills.

Borukhova and Mallayev stood trial together in a proceeding that lasted six weeks; both were found guilty and were given sentences of life without parole. The most damning evidence of their conspiracy consisted of cell phone records of ninety-one calls exchanged between the two in the three weeks preceding the murder, along with bank records showing deposits of nearly $40,000 made by Mallayev (although not directly traceable to Borukhova) on separate occasions before and after the shooting.

Of this case, widely regarded as open-and-shut, Janet Malcolm, who attended the trial, has given an account rich in perplexities. She does not directly challenge the guilty verdicts handed down; but she does raise enough incidental questions of bias and suggest enough alternate ways of reading some of the evidence as to place the entire proceeding under the shadow of doubt. Iphigenia in Forest Hills is a garden of forking paths where at every turn new and contradictory narrative byways open up. It is a brief book but immense if measured by the implications that can be teased out of its sentences—not to mention the spaces between the sentences. By the time we are done the certainties of legal evidence and judicial decisions have given way to a fundamental and unappeasable ambiguity.

Those are articulated at the outset in a remark by the presiding judge at the trial (Robert Hanophy, of whom more later) appended by Malcolm as epigraph: “Somebody’s life was taken, somebody’s arrested, they’re indicted, they’re tried and they’re convicted. That’s all this is.” In opposition to this cut-and-dried dismissal of any residual impulse to probe deeper, she juxtaposes the words of a prospective, ultimately unselected juror: “Everything is ambiguous in life except in court”—an observation of a sort in which Malcolm’s books abound, posted like warning signs to the reader to beware of the astringent clarity of each separate element as it comes into view. We want the elements to add up to a satisfying and coherent story. But as Anton Chekhov wrote—in a letter quoted by Malcolm in Reading Chekhov: A Critical Journey (2001)—responding to a reader who had complained of the writer’s having evaded a proper explanation of his protagonist’s motives: “We shall not play the charlatan, and we will declare frankly that nothing is clear in this world. Only fools and charlatans know and understand everything.”

A law court is not a bad vantage point for taking note of folly and charlatanry, but Malcolm does not exempt anyone from bias: “We go through life mishearing and mis-seeing and misunderstanding so that the stories we tell ourselves will add up.” Stories want to resolve themselves despite all obstacles; Malcolm’s peculiar mission, here as elsewhere, is to point out the cost of such resolutions, to zero in on those details that don’t fit the main story and are thus discarded, and in the process to make manifest the unreconcilable gap between an acceptable master narrative—the version that everyone must agree on in order to keep moving forward—and the specific qualities of what actually happens.

She lingers on points that might seem moot in the light of subsequent events: for example, whether the fingerprint expert who verified Mallayev’s prints was biased by his having known that Mallayev had already been incriminated by the cell phone evidence. She is not imputing bias on the part of the expert, although she cites in detail an analogous case in which such bias played a destructive role; at the very least she makes it clear that if there had been bias we would have no way of knowing. We take on faith an expertise that may be just another illusion, relying on a forensic method that may (according to a National Research Council Report) be deeply flawed, with the jury’s verdict burying any misgivings. In like fashion she takes on, one after another, the building blocks with which an unassailable story may be constructed.

Advertisement

Law in this light becomes the mechanism whereby certain lives, certain realities, are permanently buried in the interest of pragmatic social ends. Its truth is not an expression of reality but a symbolic plaque set up in place of reality, like the decorative mosaics adorning the Queens Supreme Statehouse, “a sort of mad allegory illustrating concepts…that relate to a court of law.” Malcolm spends several pages on these mosaics—leaving her story behind her almost as one would step out of a courtroom for a breath of air—in a digression that is not really a digression but the underscoring of an aesthetic principle. All that comes into view imposes, in the moment of its visibility, its own relevance. The random glimpses, here, of “figures, set in a sinister landscape crowded with waterwheels and mountains and roads and rainbows and blue bowls filled with gold”—the muralist’s barely decipherable and barely noticed allegory—make apparent the impossibility of stepping outside the domain of competing narratives that is the world.

Malcolm takes every opportunity to emphasize the unsettling quality of that competition. The atmosphere she establishes is quite different from the sealed-off environment that most jurors experience. To sit as a juror is to start with a tabula rasa: a juror is presumed to know nothing, and if a juror does know more than a very little he is likely to be disqualified. There is a “once upon a time” quality to the way the lawyers’ narratives fall on the ear in that tightly controlled setting. One is given not one but two tales, unfolding as if in a vacuum, and then given a choice of which one to believe. A juror finds himself unnaturally focused on the minutiae of the information he is being given—there are no distractions as in ordinary life—while being given no hint as to how much other information has perhaps been withheld, or the degree to which this apparently open forum is a performance stage-managed according to undeclared rules and prior understandings. The life of the courtroom is indeed a parallel life, sitting in detached judgment on the other one.

“The truth is messy, incoherent, aimless, boring, absurd,” Malcolm has written elsewhere. “The truth does not make a good story; that’s why we have art.”1 The paradox of Malcolm’s writing is that all her art is deployed to reveal the seams and interstices of the art-making process, to lay bare the details fudged or blurred or condensed, the inconvenient incongruities and confusions regularized or omitted, the bias by which certain details are foregrounded and others tossed aside. “Art” here would be the art of narration practiced by lawyers and journalists equally as much as novelists and screenwriters. Such ploys and devices are survival tactics, necessary acknowledgments of natural limits, and to focus relentlessly on them might at moments seem an exercise in relativism or equivocation. Judge Hanophy’s impatient “they’re indicted, they’re tried and they’re convicted” would sum up such a response neatly. Malcolm follows a trail of “what if”s that can lead away from the question of what is legally actionable into speculation on different kinds of guilt and how small actions may make the difference between vastly different outcomes.

The judge figures as a convenient spokesman for an approach diametrically antithetical to Malcolm’s. She makes no secret of her first and enduring impression of him: “Hanophy is a man of seventy-four with a small head and a large body and the faux-genial manner that American petty tyrants cultivate.” Neat minimalist caricature is linked to a broad implied landscape of social life, and she enriches the portrait with a devastating account of Hanophy’s intemperate and utterly irrelevant tirade against the English at a sentencing in 1997, an outburst that led to his being censured by the Commission on Judicial Conduct and that Malcolm characterizes as “a measure of what judges feel they can permit themselves in their courtrooms.”

The simmering hostility evoked by the judge’s first entrance in these pages persists as part of the book’s permanent atmosphere, flaring up from time to time, and taking on fresh importance when Hanophy, in the closing days of the trial, forces the defense to deliver its summation with very little preparation time in order not to delay his vacation: “This trial is going to be over on March 17th because I’m going to be sipping piña coladas on the beach in St. Martin.” (This and other such remarks have helped form the basis of an appeal to overturn the verdict currently being brought by the lawyer Alan Dershowitz.2) In a book dedicated to flushing out unsuspected strands of ambiguity, Judge Hanophy stands as a sort of strident emblem of the unambiguous.

Advertisement

In what pertains to the crime itself, there is relatively little here of what would be at the center stage of a typical journalistic account: the violence and chaos of the murder scene, the grief and shock of loved ones, the unraveling of the roots of the conspiracy. Malcolm avoids anything that would conjure the film noir atmosphere of Double Indemnity, and in fact devotes remarkably little space to Mallayev, the man who actually fired the shots. He becomes almost an accidental appendage of the case, a functionary of dubious connections (the court was told of an inexplicable multimillion-dollar bank loan he was granted despite being heavily in debt). He becomes visible only in his final statement—“rambling, confusing, entirely unpersuasive, but strangely dignified”—before sentencing: “What they try to accomplish is to satisfy the people of New York hey we got the killer. Don’t worry. You can go to the playground. Nothing is gonna happen.” Malcolm is always interested in any turn of phrase that seems like an inappropriate intrusion into what she describes as “the artificial and, you might even say, inhuman character of courtroom discourse.”

As for Borukhova, she is everywhere and nowhere. Every page is permeated by her aura, but seen close up—even on the witness stand—she breaks apart into a succession of versions mediated through slightly different narratives. Malcolm goes so far as to put her own impressions in question by admitting at the outset to a “sisterly bias” toward Borukhova, and acknowledging that had she been a prospective juror she would not, had she been candid, have survived the voir dire. Reporting a conversation with the court-appointed Russian interpreter, she describes the two as sharing the sense that Borukhova “couldn’t have done it and she must have done it.” Others perceived her as “manipulative” or “cold” or “obsessed.” Some jurors later said that her appearance on the stand had sunk the defense’s case because of her unnaturally aloof demeanor. In general, it would appear, “Borukhova’s otherness was her defining characteristic.”

Malcolm is less concerned with imagining the unknowable “real” Borukhova than in demonstrating the many ways in which others’ perception of her was skewed by small points of language and behavior. A major piece of evidence—a conversation with Mallayev that Borukhova secretly recorded five months before the killing—hinged on the proper translation of a Russian phrase of which wildly different interpretations were offered. Borukhova’s testimony went awry from the start, in Malcolm’s estimation, by her relentless quibbling with the prosecutor over whether her husband had “sued” for divorce or (in Borukhova’s preferred phrasing) “applied” for a divorce. Her failure to look at the jury while she testified made her invisible to them: “I watched them not watching her.”

The trial is haunted by the earlier proceeding—“the navel of the case”—in which Borukhova lost custody of her daughter. In tracing how that event came about Malcolm comes to the heart of her book. The Iphigenia of the title is the child Michelle, with Borukhova figuring as the Clytemnestra committing violence for having been deprived of her; and Daniel Malakov, according to some of the evidence, seems to have been as little eager to remove Michelle from her mother as Agamemnon was to sacrifice his daughter. The murder itself, we are permitted to wonder, may never have happened if what had been a private story of a failed marriage had not become a public one involving a large ancillary cast of characters: social workers, psychologists, lawyers, judges.

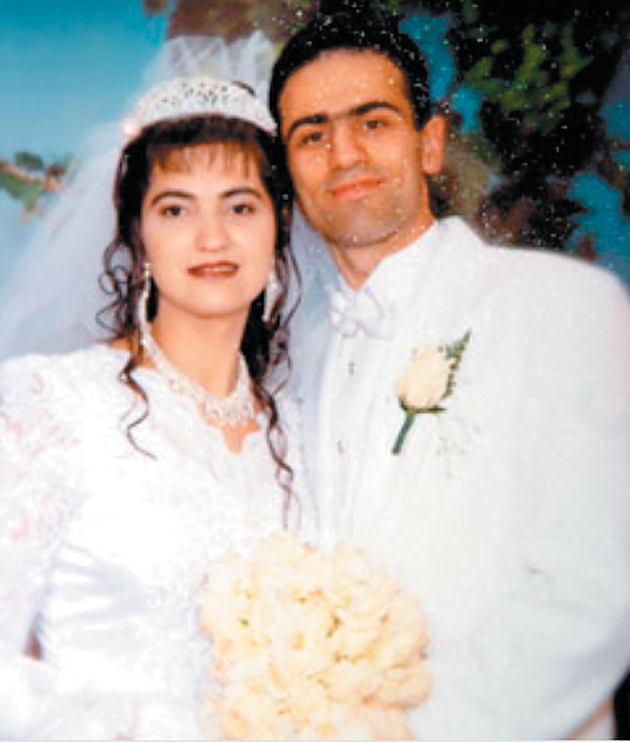

Daniel and Mazoltuv had married in 2002, against his family’s wishes (according to her testimony); they had enjoyed a relationship that from different perspectives sounds passionate, obsessive, stormy. His family told Malcolm that Borukhova had affronted the chaste norms of the Bukharan community with her provocative displays of affection to her husband. After their daughter’s birth things degenerated rapidly. There were quarrels over proper feeding and over the role Borukhova’s mother should play in raising the child. The couple separated, with Borukhova retaining custody; over a year later Malakov sued for divorce. Borukhova thereupon launched allegations in family court that her husband had sexually molested Michelle, charges dismissed when the witnesses she produced—a neighbor and a building worker—recanted their statements and said they had been “bullied” into testifying by Borukhova’s sister Natella.

At this point the Queens family court appointed a lawyer, David Schnall, as law guardian to represent the interests of Michelle. Schnall, who eventually testified for the prosecution at the murder trial, never actually met Michelle: in the Lewis Carroll–ish world of the law, it turns out that “not speaking to their clients is almost a badge of honor among law guardians.” Schnall emerges as a pivotal figure, a subsidiary presence whose influence is made to seem determining, and driven by motives difficult to determine. Between November 2005, when the case came under the supervision of the family court, and October 2007, when Judge Sidney Strauss made his custody ruling, Daniel was allowed to visit his daughter only at supervised visits at a private social agency with Borukhova present. The description of one such visit, offered in evidence before the judge, occupies Malcolm’s close attention:

Mr. Malakov constantly greets Michelle with upbeat tone and voice, a smile, and is attempting to hug her. Michelle is not responding…. Michelle does not speak to Mr. Malakov or make eye contact…. Michelle will cling to her mother…. Michelle often buries her head in the mother’s shoulder and will turn her body away from Mr. Malakov as he attempts to engage her.

The visits would end in the child crying hysterically and unconsolably.

The judgment of Strauss—couched in language of extreme personal condemnation—was that Borukhova had actively prevented Michelle from bonding with her father and that therefore the child should be immediately given in custody to Malakov. “In other words,” Malcolm writes indignantly, “the solution to the problem of a child who cries hysterically when threatened with separation from her mother while in the presence of her absent father—is to take the child away from the mother and send her to live with the father!” Malakov had not sought custody; he didn’t even want to go before the judge that day, and neither did Borukhova. It was David Schnall who pushed the matter energetically forward, serving at this point, in Malcolm’s reading, as “a powerful second lawyer for Daniel Malakov” who “fed and fanned Strauss’s fury at Borukhova.”

Schnall takes center stage in a telephone interview with Malcolm, reluctantly agreed to, in which after a brief discussion of the case he veers, for reasons known only to himself, into a more general presentation of his ideas, declaring (in a portentous credo that seems like a crude echo of some of Malcolm’s more paradoxical aphorisms): “Everything we know to be true isn’t true.” He launches into a lengthy monologue whose tone is conveyed in Malcolm’s notes:

Banks do not lend money. They have no money….

We need enemies. There will be genocidal austerity….

We’ve been living under the ten planks of the Communist Manifesto. We’re a Communist country….

Polio vaccine doesn’t cure polio. The male sperm gene is down seventy-five percent. We’re almost completely sterile….

Everything I’ve said is not opinion, it’s fact. THEY control the world.

This monologue spurs the most unexpected moment of Malcolm’s narrative—when, in her words, “I did something I have never done before as a journalist. I meddled with the story I was reporting.” She relays her notes on the conversation with Schnall to the defense attorney, who files a motion to recall Schnall for questioning regarding his mental health—a motion unceremoniously quashed by the judge.

Malcolm’s intervention was not an action that would be universally regarded as appropriate for a trial reporter. What is fascinating is that, having vividly sketched the circumstances that led to her taking this initiative, she says nothing further about her motives, and makes no comment on any afterthoughts she may have had—whether of regret or self- justification—when the motion was denied. Having for a moment turned herself into another actor in the story, she dutifully records that actor’s contribution, providing enough evidence for the reader to make a judgment, and then changes the subject when the action is of no further relevance.

There is scarcely a piece of evidence, no matter how concrete, that cannot be given contrary readings. On the day Borukhova delivered Michelle into Malakov’s custody, she arranged for a filmmaker to videotape the whole process, a tape, evidently devastating, that was shown in court:

For almost an hour, we heard the child scream until she was hoarse, as she was carried for several blocks down a street and, finally, pulled out of her mother’s arms by Daniel and taken into Khaika Malakov’s house.

This was intended to raise questions about why Michelle was so unwilling to be given over to her father’s care. But the prosecution turned it into an indictment of Borukhova’s heartlessness in subjecting her child to being filmed in that fashion.

Iphigenia in Forest Hills is not a legal brief. It goes beyond what would be regarded as relevant to the legal arguments in the case—even beyond the specific questions of guilt that the trial was about. A reader might well conclude that despite any number of possible unfairnesses in the way the trial was conducted—and despite any misjudgments and unjustifiable actions surrounding Borukhova’s loss of custody—she was indeed guilty as charged. But the ultimate legal judgment is only the beginning, not the end, of questions. In the pages that follow the verdict, as Malcolm talks with members of Malakov’s family, deeper levels of background and further shades of mystery emerge. Old stories come to the surface, about Daniel making over-the-top public pronouncements about how Borukhova was “the woman of his dreams,” about Borukhova dancing provocatively with him to the shock of the family, about Daniel’s own obsessions about the proper nutrition for his daughter, about how, back in the old country, Borukhova’s uncle had murdered his mother-in-law with an ax.

We are being led into yet another story, a story whose roots may indeed be elsewhere, in a place remote from Forest Hills and suggested by the folklorish atmosphere of the narrative elicited from Malakov’s uncle Ezra—“She wanted to stay in control like the sisters…. The husbands are like dogs for them. The husbands are afraid of them”—an exoticism akin to the Shash maqam music recorded by Ezra, music fusing Jewish liturgy and Central Asian classical modes, of which Malcolm writes:

The songs on Ezra’s recording were like no songs I had ever heard. Over instrumentation that, in its circular, teasing rhythms and vibrant twangings, evoked harem dancers, the words baruch atah adonai rang out in Ezra’s vigorous, harsh voice.

In the music another pathway opens, leading far from the matter at hand, but perhaps deeper into the world out of which these events emerged. No narrative actually ends: it is merely endlessly transformed.

Is Ezra’s music intended to hint that the book’s structure is finally musical? It is a music in which silences and the spaces between the notes count for as much as what is sounded. Every resolution is tentative and leads to a further statement that subtly displaces what preceded it by moving to a slightly different angle, establishing a slightly different frame. However much any given statement may be a model of balance and lucidity, the transitions from one to another can be brutal in their sense of disjunction. The chord that would resolve all and tell us the performance is over and we can stop listening never comes: we close the book in a state of alertness and expectancy, as if more evidence were forthcoming. A solitary, fugitive snapshot of Michelle, the daughter set adrift by this tragedy, whom Malcolm sees only for a moment in passing—“my glimpse of her face distorted by mirthless laughter”—is the closest there can be to an ending: an anticipation of future suffering. The disturbing process that has been set in motion continues after the last word. Closure is for courtrooms, not for literature.

This Issue

April 28, 2011