The death of the old Hollywood studio system can be traced back to a short, single-column advertisement that appeared in The Hollywood Reporter and Daily Variety on September 8, 1965:

Madness!!

Auditions

Folk & Roll Musicians-Singers

For acting roles in new TV series.

Running parts for 4 insane boys, age 17–21.

Want spirited Ben Frank’s-types.

Have courage to work.

Must come down for interview.

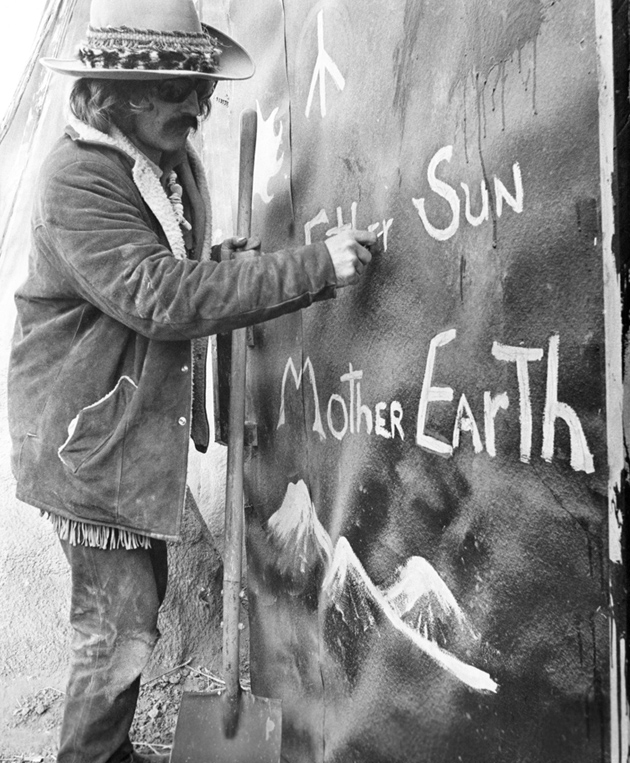

Embedded in these lines were code phrases designed to appeal to young men with certain countercultural tendencies. “Insane boys,” for instance, meant “boys who like doing drugs.” “Ben Frank’s” was an all-night diner on the Sunset Strip where musicians would hang out after the clubs had closed and wait for the drugs to wear off. “Have courage to work” meant “Have courage to abstain from drugs while we film the series.” Finally, “Must come down for interview” was not instructing applicants to appear in person; it meant “When you come for the interview, try not to be on drugs.”

The ad was placed by two young television executives: Bert Schneider, whose father Abe was the chairman of Columbia Pictures, and Bob Rafelson. Their idea was to make a television version of the Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night. It would be a goofball sitcom about the misadventures of four mop-headed teens who play in a rock band called the Monkees, which was created for the show. The series ran for two years and was an enormous ratings success. The Monkees sold twenty-three million records in a year, outselling the Rolling Stones and the Beatles during that period. (The songs performed by the “Prefab Four” were in fact written by Carole King, Neil Diamond, and the duo of Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart.) Rafelson and Schneider, now millionaires, started Raybert, a film production company. Drawing from the Monkees fortune, Raybert financed two films: the first, directed by Rafelson, was a psychedelic movie about the Monkees, called Head. The second was a much lower-budget biker movie, tentatively called The Loners, pitched by two actors, Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda.

The Monkees were soon mocked for not having played on their own recordings; Head closed in five days. The biker movie, which was ultimately released as Easy Rider, was shown at the Cannes Film Festival, where Hopper won the award for best film by a new director. It opened at the Beekman Theater in New York on July 14, 1969, and went on to make more than $19 million at the box office—roughly forty times its budget. The studios had experienced a steady, ten-year decline in revenue, and they were, as Joan Didion wrote in these pages at the time, “narcotized” by Easy Rider’s success.* Peter Fonda joked that when the film became a hit, Columbia executives stopped shaking their heads in incomprehension, and began nodding their heads in incomprehension. Peter Biskind, in his gossipy, absorbing history of the period, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls (1998), draws this conclusion:

The most concrete result of Easy Rider’s success was the legitimation of the Raybert idea, and the transformation of the company into a significant cultural force. It not only made a big movie, it defined a sensibility, opened Hollywood to the counterculture.

The “Raybert idea” was, in effect, that young creative types should be given money and full artistic freedom to make whatever films they wanted. Rafelson and Schneider, who had changed their company’s name to BBS with the addition of Schneider’s childhood friend Steve Blauner, were rewarded by Columbia Pictures with a six-film contract. The most remarkable fact about the deal was that BBS was granted final cut—it would be allowed to make all six films without any interference from the studio, as long as it stayed within budget.

BBS’s example helped bring about a transformation in the way Hollywood made films. For much of the next decade, the studios ceded an unprecedented level of artistic control to a new generation of filmmakers. A partial list would include Robert Altman, Hal Ashby, Francis Ford Coppola, Terrence Malick, Stanley Kubrick, Mike Nichols, Martin Scorsese, William Friedkin, Steven Spielberg, Brian De Palma, Paul Schrader, and George Lucas. The hagiography of the period has focused on its many triumphs, and rightfully so. But much of the period’s most challenging work has remained relatively unavailable. Only recently has the growing nostalgia for the era—driven, to no small degree, by Easy Riders, Raging Bulls—led to the tentative canonization of some of these lesser-known works, through art house film series and digitally remastered DVD releases. The historical narrative, as a result, is becoming messier.

Biskind makes a persuasive argument that the New Hollywood era was undone by its profligacy—substance abuse and financial overreaching. But his main subject was the lives of the period’s principal figures and the business of Hollywood. The Criterion Collection’s nine-DVD collection of BBS films, America Lost and Found: The BBS Story, returns the focus to the pictures themselves. For the most part this is to their disadvantage. Watching these films four decades after they were made is to be reminded that unbridled artistic freedom, like any power, can corrupt. The evidence, in retrospect, was there from the start.

Advertisement

It’s not surprising that the senescent Columbia Pictures executives were befuddled by the cultural values promoted by Easy Rider: the characters preach the liberating properties of marijuana and LSD, visit an agrarian hippie commune, and snub their noses at small-town sheriffs and other authority figures. They say things like “It’s real hard to be free when you are bought and sold in the marketplace.”

But it is surprising that the executives didn’t recognize the film’s basic design. As Hopper, who directed it, says in commentary recorded for this new edition, “I thought of this as a classic kind of western: two loners, two gunfighters, two outlaws. Billy the Kid and Wyatt Earp.” Hopper’s character is named Billy; Fonda, whose leather jacket, helmet, and motorcycle are embossed with the stars and stripes, is Wyatt. Instead of holding up a bank they make a fortune smuggling cocaine across the Mexican border, and then set out across the country. They sleep at night around campfires in the desert. Motorcycles have replaced horses, but the iconic American countryside—the golden valleys, endless skyways, and diamond deserts of Arizona and New Mexico—is shot in awed glory by Laszlo Kovacs, the Hungarian émigré director of photography.

Hopper almost exclusively chose landscapes that were unchanged from the westerns of John Ford, John Huston, and Howard Hawks—three directors that Hopper cites as influences. Even the few towns the bikers pass through seem to have been chosen on the basis of their anachronistic qualities. Outside of Morganza, Louisiana, for instance, they drive past a rural community where poor black people live in Reconstruction-era wood shacks and cart around their possessions on a mule. Throughout the film the motorcycles are always driving 25 mph, a speed chosen, as Peter Fonda explains in the commentary, “so that we could see the background.” Twenty-five mph is also the average speed of a galloping horse.

At its core the film asks what it means to be an American in 1969. The answer is ambivalent, almost equal parts celebration and disillusionment. We don’t know what to make, for instance, of Wyatt’s patriotic wardrobe. At first it seems an ironic gesture, a hippie draped in the stars and stripes. But his sense of wonder when confronted with the majesty of the heartland dispels this. For all the bikers’ criticisms of small-town mores and conventional ways of life, an obstinate strain of patriotism runs through the film—in the way the landscapes are shot, the glorification of the fast metal machines, and the celebration of the idea that such an adventure could only be possible in America. Near the end of the film, at the bikers’ final campfire, the duality is made explicit. “We’re rich!” says Billy. “We did it! We’re retired in Florida now, mister. That’s what it’s all about. You go for the big money, and then you’re free.” Wyatt, impassive, stares into the fire. “We blew it,” he says.

It’s telling that this line was a subject of fierce debate for contemporary audiences and critics. Today the meaning is clear: Wyatt has become skeptical of the egoism of their journey—selling drugs to finance a life of lethargy and hedonism. He has been shaken by a rough acid trip and the brutal murder of George Hanson (Jack Nicholson), an ACLU lawyer they’ve befriended, by Southern bigots. They may have gained financial freedom, but they’ve lost their pride along the way. That this expression of disillusionment was baffling to viewers at the time is a measure of how spiritedly the film embraced the opposite point of view—the exhilaration of shirking the responsibilities of straight life and romping through the American paradise with drug money hidden in your motorcycle. Easy Rider flattered its audience’s values. The audience had changed, as had their values, but the technique was classical Hollywood.

BBS had two other critical and box office successes: Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show and, to a lesser extent, Bob Rafelson’s Five Easy Pieces. The Last Picture Show, adapted from Larry McMurtry’s novel, is in many ways a paean to old Hollywood, the title a parting salute to the end of an era. Bogdanovich first became aware of the novel while writing a profile of John Ford for Esquire. On the set of Ford’s Cheyenne Autumn, the actor Sal Mineo gave Bogdanovich’s wife a copy of the novel; Bogdanovich, who consulted with Ford during the making of the film and cast one of Ford’s favorite actors, Ben Johnson, in a central role, would later refer to The Last Picture Show as his “Ford picture.”

Advertisement

Set during the Korean War, and shot in black and white with plenty of pictorial long shots, the film is a quiet rumination on loss and despair in Anarene, a small, isolated Texas town. Cloris Leachman’s portrayal of a middle-aged woman whose loneliness leads her to seduce a high school boy is haunting and at times painful to watch; Cybill Shepherd and Ellen Burstyn play a mother and daughter who are respectively entering, and exiting, their sexual primes, with the same man. Yet the dutiful homage to a distant Hollywood era, which may have seemed radical in 1971, gives the film a leaden, enervated quality, as arid as the desert that surrounds Anarene.

Five Easy Pieces is the most consistently surprising of these films. Jack Nicholson plays Bobby Eroica Dupea, a man who has rebelled against his well-heeled, classical music–obsessed family on the Washington state coast and moved to Bakersfield, California. In the desert he works on an oil rig and takes up with Rayette (Karen Black), a ditzy diner waitress who, it is mentioned once, in passing, is pregnant with his child. But the low life is not all it’s cracked up to be. When, halfway through the film, Bobby learns that his father is dying, he returns to his family home. The film divides into two discrete sections. It’s not only that the two halves are shot in different locations, with starkly distinct color palettes (Bakersfield is pale blue, yellow, and iron rust, while the Pacific Northwest is forest green and Puget blue). They also use a completely different set of secondary characters and were cut by different film editors, who never saw each other’s work until the film was released.

But the two sections are held together by the evolving drama of Bobby Dupea. Though Bobby boasts of possessing “no inner feeling,” his emotions bristle in every gesture, every glance; Nicholson gives one of the most nuanced performances of his career. Rafelson deserves some credit for this. Often the camera lingers on Nicholson after a scene ends, especially in moments when he is left alone, and his preternatural charisma dissolves to reveal a darker emotional truth. An early example comes at the end of a scene at a bowling alley. Bobby and Rayette have gone on a double date with Bobby’s chuckleheaded coworker, Elton, and Elton’s girlfriend.

After an argument between Bobby and Rayette, the two girls storm off to the parking lot; Elton stays behind to cheer up his friend, but then he leaves too. For fifteen seconds Rafelson holds on Nicholson, sitting in the plastic booth. Nothing happens, particularly—his smile fades, he exhales, he stares forward, he looks down, he looks back up, and finally his reverie is disrupted by the waitress bringing him the bill. But in these moments Bobby’s false bravado breaks down and we see in his face the realization that he has made a terrible decision with his life, that despite breaking free from his family, he’s blundered into a new kind of prison.

Nicholson was the unofficial fourth member of BBS, involved in every production except The Last Picture Show. After ten years of appearing in westerns and Roger Corman films, Nicholson had given up acting and resigned himself to a career as a screenwriter. He was becoming a kind of specialist. In 1967 he wrote the screenplay for Corman’s The Trip, starring Fonda and Hopper, which is structured in the form of an acid trip; the next year, while holed up in a basement writing the Head screenplay, Rafelson says Nicholson had a breakthrough: “Jack saw the movie in his mind as being structured like an acid trip.” They were on acid at the time.

But as they wrote the screenplay, Rafelson became aware that Nicholson’s talents were being wasted:

I couldn’t take my eyes off him…it was the way he acted out all the Monkees’ parts. If there was an animal, he could act out the animal. A bird? He could tweet like a bird. A snake? He could slither like a snake. I could not stop looking at him. I cannot stop looking at him today.

Rafelson vowed that if he ever directed another film, Nicholson would star.

That film would be Five Easy Pieces. But it was Easy Rider, made one year earlier, that brought Nicholson his first Academy Award nomination and convinced him to put aside his screenwriting career. He doesn’t appear in the film until the forty-sixth minute, but it is at a crucial juncture—all pretenses of plot have withered and the viewer starts to fear that the two bikers will never get anywhere, that they will continue to ride through the desert, accompanied by rock music, forever. Finally they’re arrested for disrupting a parade. The following morning they wake up in a jail cell. Nicholson is asleep on the next cot. He awakes and, for the next thirty minutes, the camera never leaves him. Like Rafelson, Hopper and Fonda can only stare at him, his crazed energy causing them at several points to break character. Nicholson’s face is always working, a pantomime of bared teeth, perverse yawns, snide grins, despairing glares, and eyebrows pointing like circumflexes. “He saved the movie,” says Steve Blauner in a recent interview, still grateful after forty years. He’s right, as is his larger implication: if Nicholson saved Easy Rider, that means he saved BBS.

Nicholson is also the best thing about A Safe Place, an incoherent collage that may not be structured like an acid trip but induces the same effects as one. (Orson Welles appears, inexplicably, as a street magician who levitates a large silver ball.) In the only memorable scene, Nicholson, who plays an ex-boyfriend of Tuesday Weld, shows up at four AM in the small apartment she shares with her nebbishy boyfriend; Nicholson and Weld begin having sex in the living room, and the boyfriend runs out in tears. Nicholson directed Drive, He Said, a campus drama that is poorly acted and relies heavily on the clichés of the period—grandstanding student revolutionaries, free love, and paranoid conversations about theater, war, and the “theater of war.”

In The King of Marvin Gardens, Rafelson cast Nicholson against type, as the sedate, introverted intellectual to Bruce Dern’s manic grifter. It was a bold artistic decision; a bad one, too. Although there are mesmerizing shots of off-season Atlantic City—vacant ballrooms, deteriorating grand hotels, bonfires on the beach—the drama is too outlandish to be convincing. If the roles were reversed, Nicholson might have been a good enough salesman to put it across.

Still, it’s worth noting that these three films, along with Head, were the most innovative that BBS produced. They represented new approaches—directors were allowed to pursue their most radical ideas about filmmaking, basic storytelling principles were flouted, and familiar conventions were held up to ridicule. This is especially true of Head, an extended riff on the phoniness of Hollywood and the Monkees themselves. But the films were failures and, with the exception of Marvin Gardens, embarrassing ones at that: tedious and pretentious, with alternating currents of silliness and melodrama. For the most part they fail because the characters are dull, unlikable, or not credible, so the dramatic stakes are never very high.

Marvin Gardens was the final BBS release, and the contract with Columbia wasn’t renewed. In the years that followed, the studios discovered the mega-blockbuster (Jaws and Star Wars) and returned to their old business formula: the star vehicle. Nicholson was perfectly positioned; BBS, with the auteur model it championed, was not. Nothing like BBS has emerged in the four decades since. The blockbuster franchise is still alive, but teetering. As for the bankable movie star—the actor so popular that his appearance in a film guarantees it will turn a profit—we are down to one: Will Smith. The only players in Hollywood who are granted real freedom to experiment are the technicians. They’ve been making great strides, as anyone who has seen Avatar can attest. The images are becoming three-dimensional, the special effects are more staggering than ever, and the sound is uncannily crisp. Something is missing.

This Issue

May 26, 2011

-

*

See “Hollywood: Having Fun,” The New York Review, March 22, 1973. ↩