Charles Murray has written another book about race. Much as The Bell Curve1 argued that many human beings of African heritage were genetically less intelligent than most whites, so Coming Apart addresses the deficiencies of Americans of European origin. He charges large swaths of “white America”—his designation—with indolence, self-indulgence, and failing to understand the nation’s “founding virtues” of honesty, industriousness, marriage, and religion. An air of despair pervades the book. Those whose forebears did so much to build this country lack the kind of resolution the coming century will need.

1.

Murray says he chose to focus on whites so he could conduct his analysis of changes in American society “independently of ethnic heritage.” He omits Asians and Hispanics because most are relatively recent arrivals, just as having African origins brings burdens of its own. This leaves some 200 million people—now 69 percent of the population, down from its 90 percent height in 1950—who told the most recent Census they consider themselves fully white in that they did not add another ethnic designation. As noted, he excludes everyone who identifies as Hispanic, even though half of them add that they are also white. (The 2010 Census form asked respondents both if they were of “Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin” and their race—white, black, etc.) Several generations in Chile apparently would weaken a claim to European ancestry. Nor does he subdivide his white grouping by national origins or religious ties. Here he recognizes that each year sees further assimilation among white Americans, with surnames a last reminder of where they came from.

But Coming Apart is also a book about class. Or more precisely, two contrasting classes of white Americans. One, a “new upper class,” includes not just the rich and powerful, since it takes in a generous 20 percent of the population. By my calculations, it starts with families earning $135,724. The other, a “new lower class,” is everyone in the bottom 30 percent. Its top income, also by my count, would be $52,057. Nor are these classes wholly economic; Murray adds educational and occupational status to give a more rounded portrayal. Thus everyone in his upper class must have completed college and hold a professional or managerial position. He explains what makes both these classes “new,” and why conventional rubrics no longer apply. No discussion is given to the remaining 50 percent, which is odd, since they are literally mid-America and cast most of the votes in presidential elections.

2.

Murray believes that a new designation is needed to characterize a large part of the white population. In the past, it was called a working or blue-collar class, which emphasized their mode of employment. It was a given that such people applied themselves at their jobs, whatever their level of skill, and took family responsibilities seriously. Union wages meant they could own modest homes and send a large proportion of their children to college.

Today, in Murray’s view, this ethos barely exists. As he sees it, “prime-age” whites in this class, particularly men in their thirties and forties, frequently refuse to take available jobs, and put in fewer hours when they do, often by feigning disabilities. By his count, most of them are divorced, separated, or reluctant to take the plunge into marriage. Men who do aren’t much better, at least in a Philadelphia neighborhood he writes about. (The women “almost got an extra son at home, better known as the husband,” as Murray quotes the head of a parochial school.) More than a few engage in activities that end them in prison. At times, Murray refers to them as “rednecks” and “rabble,” not entirely tongue-in-cheek.

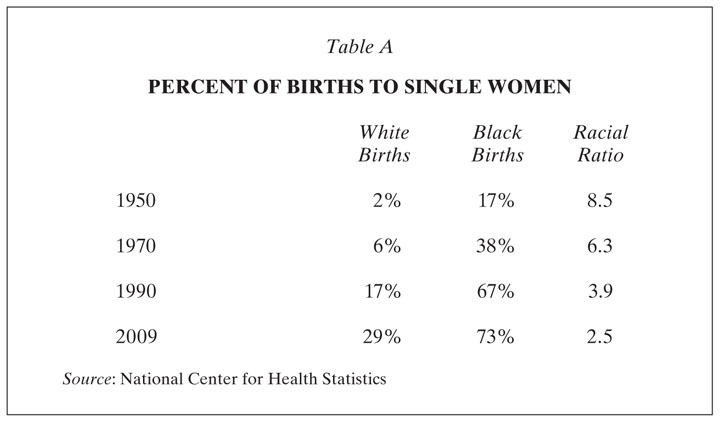

A generation ago, the term “underclass” was current, spurred by fears of urban violence, promiscuous procreation, and soaring welfare rolls.2 An unstated premise was that almost all in that class were black, since whites couldn’t fall that far. Murray holds that the Great Society’s benefits sent a something-for-nothing message to the larger society. Starting in the Sixties, whites began to become entwined in the “tangle of pathology” Daniel Patrick Moynihan had ascribed to black Americans. Thus as Table A shows, each year sees white extramarital births coming closer to the black rates. But this presents a challenge for Murray, which he sedulously sidesteps. As was made clear in The Bell Curve, he believes that racial gene pools for traits like intelligence are real, and “black” and “white” are not just rubrics. So does he take the moral deterioration he sees in whites as a sign that a major human race is losing its power to adapt and compete? Murray does no more than imply it is the case.

Murray begins by praising his new upper class. They are staying married and they say they attend religious services regularly. (No distinctions are made between, say, Episcopalians and evangelicals, even as the latter have their share of college graduates.) They are lauded for being “engaging, well mannered, good parents, and good neighbors.” He admires their social and professional skills, dubbing them a “cognitive elite,” educated for a fast-changing world. Yet their ascent has made them “increasingly isolated” from the rest of society, with “large areas of ignorance about how others live.” Murray supports his point by setting his upscale readers a quiz: When did they last watch Judge Judy or dine at a downmarket Applebee’s? This isolation and ignorance set his new upper class apart from its predecessors. Murray tells of the Iowa town of his youth, where the banker exchanged pleasantries with the local butcher on the street.

Advertisement

Then, without warning, Coming Apart turns harsh. We hear his top class described as “overeducated elitist snobs” who “believe that they and their peers are superior to the rest of the population.” At this point, the book relies heavily on David Brooks’s lampoon of “bourgeois bohemians.” So we hear anew about people who are drawn to spiced apple cider sorbet and spinach feta loaf, health clubs and marathons. The implication is that those at the top are frivolous and self-centered. But statistically this doesn’t fit. Murray chose to make his upper class large, encompassing one of every five Americans. While they may all be college graduates, they range from Yale art history majors to Iowa State engineers, and cider sorbet to burritos at Super Bowl parties. Still, Murray has mounted a grave indictment of his fellow white Americans, starting at the top. For all their cognitive cleverness, they are “an elite that is hollow at the core” and “as dysfunctional in its way as the new lower class is in its way.”

Coming Apart has little to say about the economic conditions that create Murray’s classes. He requires a college degree for membership in his new upper class, since symbols, words, and numbers are its basic products. I occasionally found myself wondering if this isn’t a grand illusion, a fantasy about modern mandarins who feel they can master the universe with spreadsheets and economic models in a world where financial and military decisions rest on differential equations and PowerPoint presentations. Nor am I persuaded that verbal sophistication (“critical thinking,” “moral reasoning”), as defined in academic assignments, necessarily improves productivity. Still, the economy has found funds to underwrite this assumed elite, largely by paying less for blue-collar work, whether performed at home or abroad.

What makes Murray’s new lower class “new” is its tenuous tie to the labor force. The country once had a substantial industrial base, which was predominantly white. While Murray grants that there are fewer Detroit-type jobs, he doesn’t mourn the eclipse of organized labor. (“Unions usually do not play a large role in generating social capital.”) The problem, in his view, is that all too many of his newly lower-class men are what the English once called “work-shy.” Murray tells us that office cleaners average $13.37 an hour, which adds up to an annual $26,740. What one takes home from that, he says, should be “enough to be able to live a decent existence,” adding, “even if you are married and your wife doesn’t work.” So Coming Apart calls for a serious change in attitude, from which will emerge a new post-union class, grateful for $26,740 offers. (The current poverty threshold for a family of four is $23,050.) This altered outlook, Murray says, should enhance interclass comity. Janitors thankful for their jobs will not begrudge $267,400 to recently minted MBAs whose offices they are cleaning.

3.

Murray has always been fascinated by genetic inheritance, whether within entire races or specific pairs of parents. Among his white “cognitive elite,” he says he sees a rise in “the interbreeding of individuals with like characteristics.” With women now receiving more than half of postsecondary degrees, credentialed couplings become common. “When individuals with similar cognitive ability have children,” Murray tells us, “the staying power of the elite across generations increases.” The traits passed on by the partners may be cultural, like diction and demeanor, or intrinsic, like a gift for mathematics or music. Unlike its predecessors, the new upper class will not be based altogether on privilege; it will be more like a hereditary meritocracy in place because of its greater share of society’s intelligence.

To reinforce this point, Murray says research shows that “graduates from elite colleges are likely to marry other graduates from elite colleges.” At first glance, this seems to make sense. Dartmouth and Duke are congenial milieus for young people to meet, even if nowadays a decade may go by before they marry. However, the source he cites doesn’t support this supposition. For one thing, it dealt not with recent graduates, but with men and women who were aged fifty-eight through seventy-two when the article appeared.3 Moreover, less than a quarter in this sample chose spouses “from colleges with the same institutional characteristics.”

Advertisement

For an updated test, I undertook an informal inquiry of my own, which suggests that Murray is only half right. In marriages listed in The New York Times during the first three months of this year, among the couples where at least one spouse had an Ivy-tier degree, in almost half the other did as well. Among the rest, Yale and Stanford graduates chose mates from schools like Baylor and Michigan State.

We know that well-off and otherwise accomplished parents can give their children a good start, or at least try. So the next question is how these presumably favored offspring fare as adults. Such studies as we have suggest that early advantages don’t always last. Tom Hertz, an economist at American University, found that of children raised in families in the top income quintile, only 38 percent were still there as adults. Ron Haskins at the Brookings Institution, also following top-quintile youngsters, was surprised to find that only a little over half (53 percent) obtained college degrees.

Claudia Dreifus and I conducted a similar study for a book we published two years ago.4 We chose a full Princeton class, giving its 883 graduates time to have offspring of college age. We estimated, on the conservative side, that together they had 1,500 children. As it turns out, only 120 of them applied to and were accepted by Princeton—with or without legacy preferences—while about 180 applied but were rejected, which is itself a commentary on elite inheritance.

Of course, not all young people wish to attend their parents’ school, even if they could get in. In our Princeton case, the book produced for the class’s reunion reported where many of them went. In fact, only two ended at Princeton-tier schools: one each at Harvard and Cornell. Some of the rest landed at Lehigh, Wake Forest, Denison, Penn State, Carleton, UCLA, Tulsa, Northwestern, NYU, Virginia Tech, and the University of Scranton. We leave to others whether we’re seeing downward mobility or simply regression to the mean. In any case, excellent educations can be had at these and similar colleges. The larger point is that most seats at elite institutions now go to applicants—many born abroad—whose parents attended less highly ranked schools or none at all. Murray will have to do more research if he is to prove that America’s elite is becoming more hereditary.

4.

Honesty is one of Murray’s four “founding virtues”—along with industriousness, marriage, and religion—which he sees imperiled. As a measure of that quality among Americans—or its lack—he cites incarceration rates for white adults, which have been steadily rising. While most prison inmates are black and Hispanic, a not negligible 850,000 white men and women are also behind bars. He provides detailed data on arrests and sentencing, as well as probation and parole. “Whites in state and federal prisons,” Murray adds, “are overwhelmingly drawn from working-class and lower-class neighborhoods.” It’s probably true that most people who are convicted did something illegal. But looking only at who ends up in prison serves to make dishonesty largely a lower-class failing.

On honesty among his upper class, Murray concedes the “damning evidence of systematic wrongdoing” in the financial world. Even so, he says he is “not clear” on how far “a decline in personal integrity” has spread among the better-off. For so broad an assessment, prison statistics aren’t much help. If Martha Stewart, Bernard Madoff, and Raj Rajaratnam come to mind, not many more can be readily named. In white lower-class circles, almost everyone can point to a friend or relative or neighbor who’s been convicted. This is seldom the case among the middle class. Indeed, its members prefer not even to suspect there could be felonious conduct by people they know.

As it happens, information is available. In 2006, the most recent year for figures, the IRS estimated that it failed to receive at least $450 billion, because of failures to file, underreporting, underpayments, and bogus deductions, most of these conscious attempts to evade taxes. There is reason to suspect that tax evaders come largely from Murray’s top 20 percent. Certainly, this fifth contains corporate executives and their counselors, some of whom are periodically caught violating laws. Almost every week, the invaluable Corporate Crime Reporter tells of yet another bank or brokerage house conceding that its employees committed security fraud; the same source tells of pharmaceutical firms admitting that people on their payrolls fixed prices or marketed products illegally. Usually, however, only the corporate entities are charged, not the executives who planned or tolerated the felonies. The firms are almost always allowed to pay fines and settle silently, without admitting wrongdoing. Prosecutors argue that this is the best they can do, since it’s hard to prove malicious motives to a unanimous jury. (Insider trading cases are easier, since they’re often built on whistleblowing or tapped information.)

Is there a tacit agreement to spare executives from hard time? The Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, based at Syracuse University, has the only count I’ve seen of financial prosecutions that ended with sentences. In the twelve months ending in November 2011, the ninety-four US Attorney Offices nationwide recorded a total of 719 cases where the defendants were sent to prison.5 Murray seems to see low numbers like these as evidence of upper-class honesty. Hence he cites a 2005 IRS figure that of 31 million tax filings by corporations, proprietors, and partnerships, only 217 penalties were assessed for civil tax fraud. He does not seem aware of the Corporate Crime Reporter findings. Moreover, he does not ask how many of those filed returns were carefully reviewed for fraud; nor does he ask how often prosecutors, presented with evidence that suggests fraud, choose to press charges. (The statistics on the proportions of returns actually reviewed and the numbers of these that showed inadequate payment could be revealing but aren’t provided here.)

5.

For his own part, Murray himself shows every sign of being what white connotes. He was raised in Newton, Iowa (1960 Census: 99.6 percent white, 98.4 percent native-born). He laments that citizens of his stock have lost their moral compass. Apart from blaming Lyndon Johnson, he seeks no deeper explanation behind his race’s fall from grace. Is it wholly implausible to suggest that white America’s time of power and preferment is coming to a close, both at home and abroad, and that such vigor as remains is being devoted to personal acquisitions and enjoyments? Hence a desperate air among Republican aspirants—after all, we know the race of the party’s base—hoping for a last hurrah as their era ends. Even if demography isn’t always destiny, it should never be discounted. To start, white Americans aren’t having enough children to maintain themselves. The nonwhite population is certain to keep growing, from immigration and reproduction. Jonathan Chait forecasts that in only thirty years they will be the majority of the electorate.6

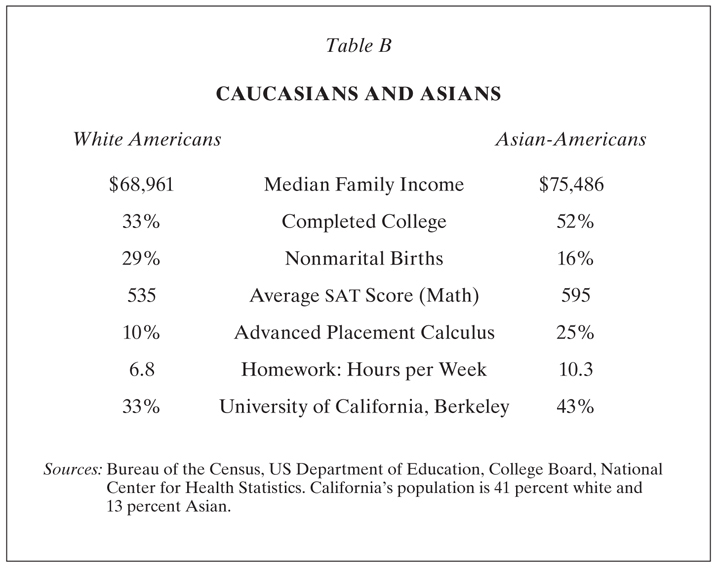

Evidence of white eclipse is actually close at hand. Murray says little about Asian-Americans, other than that he sees their basic traits as “similar to those of whites.” Here he’s very wrong. In vital respects, they differ markedly, as the entries in Table B show. That Americans of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Indian descent work harder and more effectively is widely recognized, not least their excelling in competitions whites created. Nor from the many accounts I have seen does this drive center on the self. Bringing honor to one’s family is the major goal; a traditional impetus fosters mastering the modern world.

From Princeton to Berkeley, each year sees more places going to Asians on merit, with fewer white faces evident on competitive campuses. I wonder whether Murray would want to argue that if his whites were to truly apply themselves, they could match Asians on the SAT. (Currently, Asian women outscore white men.) Since he makes so much of genetics, does he think we are seeing signs of deterioration in the white strain?

Murray’s coda returns to his title: “our nation is coming apart at the seams.” The cause, as he sees it, is a preoccupation with self at every social level. Suburbanization segregates the highly verbal from those who do most of the nation’s work. In Murray’s vision, we were to be not only a union of states, but a unified society. Thus the conservative mantra that any discussion of inequalities of income or privilege will set citizens against one another, indeed foment class warfare. While Murray doesn’t begrudge his cognitive elite its often lavish pay, he expresses concern over the “unseemliness” of much corporate conduct. A responsible ruling class doesn’t flaunt megamansions.

Murray wants a modern noblesse oblige: not just checks sent to charity but actual mingling, perhaps at Applebee’s. And, like Edmund Burke, he would have his lower class accept “their appointed place,” embracing honest labor and respect for authority. Nor is this entirely a pipe dream. When the Republicans muster majorities, they do it by rousing white voters below the median, lauding them as the nation’s bulwark. But such a strategy calls for casting other citizens as disloyal, undeserving, or immoral, not exactly a recipe for binding the nation together.

6.

Murray’s reconfigured classes have emerged as if out of the air; they are not the product of organized interests or deliberate policies. Here Timothy Noah’s The Great Divergence is a welcome antidote. He does not simply show the glaring increase in inequality since the 1960s. Almost every year has seen more of the nation’s income ascending to its higher layers, whether the top quintile, one percent, or the four hundred wealthiest families. He also shows how top tiers in management and finance devised ways to arrogate more money for themselves, at the same time using their political power to decimate unions. Noah observes that jobs aren’t sent offshore just for lower wages. Using foreign labor also offers relief from assertive American workers. I particularly recommend Noah’s list of solutions. He’s all for enlarging public payrolls, with WPA-style projects, rather than enriching private contractors. He would hire more IRS auditors to bring back revenue from Swiss banks. I especially second his call to “impose price controls on colleges and universities.” The increasing dependence of students on loans is creating a new indentured class.

Since his book is both much needed and a delight to read, the one caveat I have is offered in good spirit. On immigrants, I fear Noah relies too heavily on models purporting to show how wages have dropped because “undocumented” workers were more and more employed. Across the workforce, it may well be 2.3 percent or 3.7 percent, depending on your source. But those who feel the harshest impact are forty-year-olds who can’t see themselves in those $13.37 per hour jobs, which Murray turns into a commentary on their character. Such wages are accepted by—indeed, geared to—immigrants, who in their early years here are willing to sleep five to a room. Their prominence in meatpacking plants, kitchens, and twelve-hour taxi shifts not only attests to the function they perform in the workforce, but undercuts any consensus on a coherent immigration policy. Their presence is deplored by politicians while their services are sought by business managers. At all events, fewer businesses, including subcontractors for the largest ones, are willing to pay what were once viewed as “white wages.”

Noah knows, however, that as things stand, he cannot expect much when he calls for reregulating Wall Street, giving unions greater support, and making the rich contribute more in taxes. But he believes that his demonstration of growing inequality and his proposal to remedy it are worth a book. In contrast, it isn’t clear what’s the point of Coming Apart. Without much conviction, Murray calls for a quasi-religious “awakening.” Apart from this, he doesn’t feel that much can be done about the self-indulgence and indolence of his archetypal lower and upper classes. In fact, his world-weariness isn’t just about two classes and one race, but an entire nation facing a daunting century.

-

1

Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray, The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (Free Press, 1994); see the review by Alan Ryan, The New York Review, November 17, 1994. ↩

-

2

See “The Lower Depths,” The New York Review, August 12, 1982. ↩

-

3

Richard Arum, Josipa Roksa, and Michelle J. Budig, “The Romance of College Attendance,” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, Vol. 26 (2008). ↩

-

4

Higher Education?: How Colleges Are Wasting Our Money and Failing Our Kids—and What We Can Do About It (Times Books, 2010), pp. 71–76. ↩

-

5

“Fraud-Financial Institution Prison Sentences,” TRAC Reports, March 5, 2012. ↩

-

6

Jonathan Chait, “2012 or Never,” New York magazine, February 26, 2012. ↩