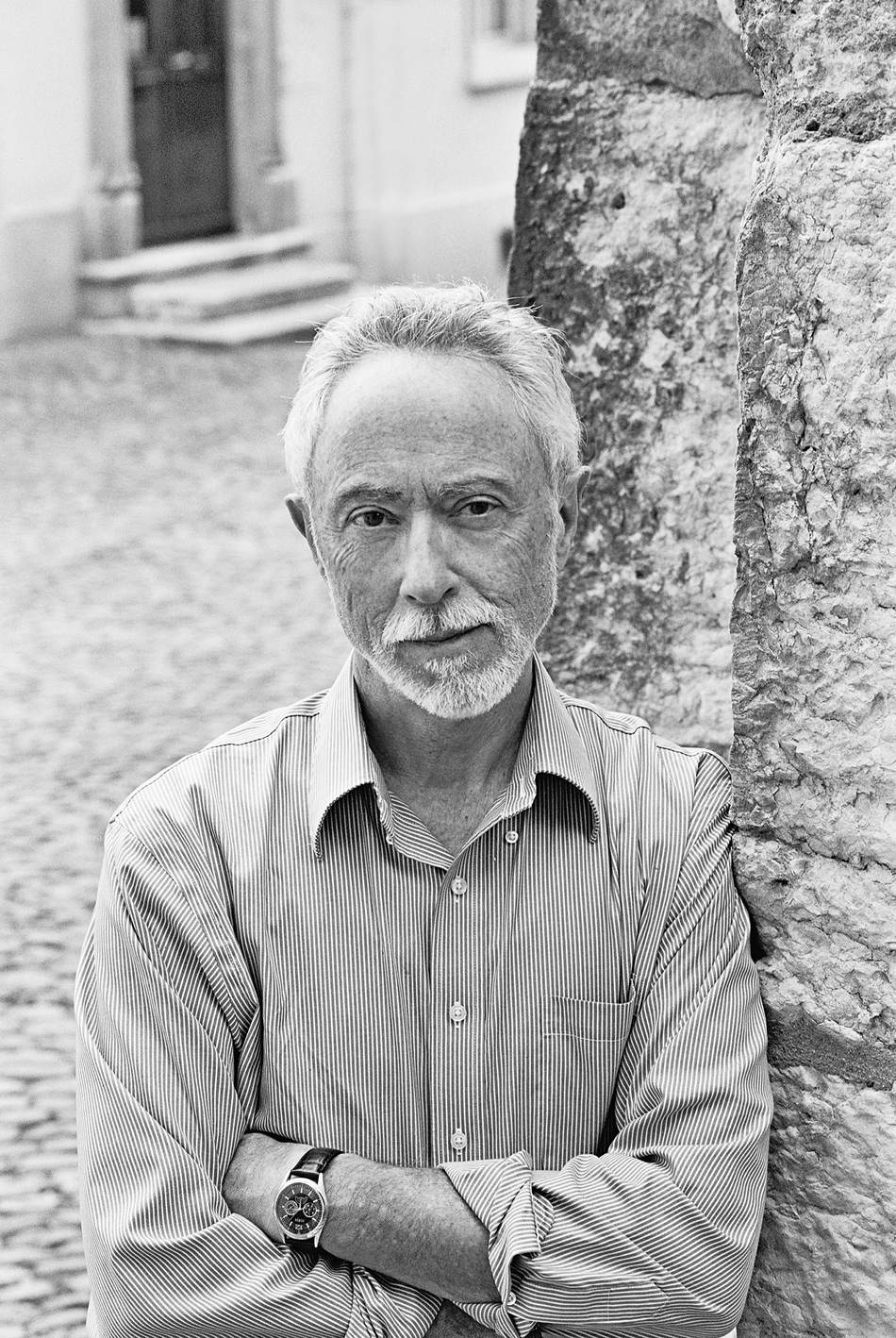

In two of his letters to Paul Auster, written in the fall of 2009 and recently published in Here and Now,* J.M. Coetzee considers the idea of “late style”:

It is not uncommon for writers, as they age, to get impatient with the so-called poetry of language and go for a more stripped-down style (“late style”). The most notorious instance, I suppose, is Tolstoy, who in later life expressed a moralistic disapproval of the seductive powers of art and confined himself to stories that would not be out of place in an elementary classroom…. One can think of a life in art, schematically, in two or perhaps three stages. In the first you find, or pose for yourself, a great question. In the second you labor away at answering it. And then, if you live long enough, you come to the third stage, when the aforesaid great question begins to bore you, and you need to look elsewhere.

He returns to the subject, which is obviously on his mind: “Late style, to me, starts with an ideal of a simple, subdued, unornamented language and a concentration on questions of real import, even questions of life and death.”

These thoughts on “late style” were hardly, for Coetzee, abstract musings. He was then approaching his seventieth birthday, which presumably still counts as a biographical eleventh hour. (He is now seventy-three.) Perhaps more importantly, his need to “look elsewhere” is palpable. Coetzee’s last novel, the wonderfully playful but often self-lacerating autobiographical fiction Summertime, began and ended with the desire to escape, to free himself from the burden of responsibility to history and family. That book marked a literally final reckoning with his own career in and beyond his native South Africa: its conceit is that John Coetzee is dead and that those who knew him best are being interviewed by a sometimes obtuse biographer.

To complete the joke, we might say that his new novel, The Childhood of Jesus, is therefore not so much a late work as a posthumous publication. It is a writer’s afterlife, Coetzee after Coetzee. As the central character, Simón, explains to David, the young boy for whom he has become a surrogate father, “After death there is always another life…. We human beings are fortunate in that respect.”

In the mysterious place to which they have both come, “None of us has a past. We start anew here. We start with a blank slate, a virgin slate.” An important recurring phrase in The Childhood of Jesus is “washed clean”—clean of all attachments, clean of memories, clean of the past. The novel itself can be seen as Coetzee’s attempt at a blank slate, his excursion into a fictional universe from which all the things that have clung to his previous work, often in spite of itself—politics, history, sex, family—have been scrubbed away at last.

Its fascination is that it fails. It betrays a deep uncertainty about the project of a “late style” that weakens it as a novel but that will enthrall Coetzee’s admirers. It shows him in two minds: determined to begin again without entanglements or memories but worried that such a world may be an arid place. For perhaps the first time in his brilliant career, this most self-assured of stylists seems anxious that his new world may be a no-man’s-land in which he cannot locate significant landmarks. The tension is, in its own way, oddly gripping.

The publishers describe The Childhood of Jesus as an “allegorical tale,” but this is misleading. An allegory has a clear correlative outside itself, a parallel reality or narrative with which it resonates. Here, there is no such parallel. There is some vestigial relationship to the biblical story suggested by the book’s title. Simón, David, and Inés, the boy’s adoptive mother, form a kind of Holy Family. Simón has some very broad similarities to the uncomplaining, stoical Saint Joseph. Inés is a virgin “mother.” David is special in that he is astonishingly bright, but not in any supernatural sense. Told by his teacher to write the words “I must tell the truth,” he writes instead “I am the truth,” the novel’s most explicit evocation of Jesus.

Far from functioning as a key to the story, however, these parallels actually work in the opposite way. They are an exercise in authorial misdirection. They seem to promise the reader access to Coetzee’s meaning and instead create a deliberate sense of frustrated expectation. They really serve to emphasize how self-enclosed the narrative is, how illusory the search for any external significance. They are a warning to the reader: you know only what I tell you. Or as Simón instructs David, “For real reading you have to submit to what is written on the page.”

Advertisement

What is on the page, what Coetzee chooses to tell us, is severely limited. It does not include time or place. The action seems to unfold at some period in the second half of the twentieth century. On the docks, where Simón gets work as a stevedore, containerization has not yet arrived and loads are hauled by horse and cart. Elsewhere, there are cars and phones, television and Mickey Mouse. (One suspects that Mickey is chosen deliberately as one of the few modern points of cultural reference that elude specificity: his reign spans many decades.) There are not yet cell phones or computers.

The place is a city called Novilla and its hinterland: the name may or not be a pun on the word “novel.” We know that it is Spanish-speaking but also that it is not in Spain because Simón has to explain to David, who is reading a children’s version of Don Quixote, that “La Mancha is in Spain, where the Spanish language originally came from.” It has a bureaucracy, professions, a police force, and some kind of class system (while most of the inhabitants seem to live on bread and bean paste in austere housing projects, some live in mansions where they drink sherry and play tennis) but no apparent history or politics.

It is possible, of course, that Novilla is a literal afterlife. At one point, when David is upset about the death of a horse he had befriended, Simón tells him that the horse is crossing the sea to a place where he can “start anew, washed clean,” the same words that are applied to their own journey. Later, we learn that the harbormaster (like Charon, who ferries the dead across the Styx) “won’t let anyone take the boat back to the old life…. No return.” But like the vestiges of the Gospel story, these hints of a mythic setting yield very little in the way of enlightenment.

Simón, who is middle-aged, and David, who is five, arrive in Novilla at the start of the book, having been in a transit camp for six weeks. Of their previous lives we know almost nothing. They are not Spanish or English or German, since they do not initially know (or recognize) those languages. (It is possible that Simón is Jewish or Muslim, since he has a strong aversion to pork, but this amounts to nothing more than a passing suggestion.) They were not originally called Simón or David—these are new names given to them at the transit center as part of the washing clean of the past. They are not related. They met on the boat that brought them to this new place.

David lost the letter that identified his mother in Novilla, and Simón, for reasons that are not clear to us, has taken full responsibility for the child. He has also, again for reasons that remain elusive, convinced himself that he will recognize David’s mother as soon as he sees her. In the end, and again for no apparent reason, he settles on the virginal Inés, who, for similarly obscure motives, claims the boy with an obsessional possessiveness. Nothing much happens until David is sent to school, gets into trouble with his teacher for insisting on his own private versions of literacy and numeracy, and is then exiled to an institution for troubled children. From there, he escapes and the odd little family, now with a scarcely explained last-minute addition, goes off in search of yet another “new life.”

In all of this, readers get just enough information to make us continually conscious of how little information we have. Shards of apparent fact are dangled before us, not to give us a sense of external reality but to remind us of its absence. It is never quite clear what is at stake in the novel. “Who, in this story, owes what to whom? I can’t say, and I am sure you can’t either,” the kindly foreman Álvaro at the docks tells Simón.

None of this is in itself especially troubling for anyone who loves Coetzee’s previous work. He is a consummate withholder, one of the great masters of the unsaid and the inexplicit. Coetzee, even under the enormous pressure of writing in apartheid South Africa, always insisted that his novels would not document or bear witness to reality—they would rival it. His aim, as he put it in 1987, was to produce

a novel that operates in terms of its own procedures and issues in its own conclusions, not one that operates in terms of the procedures of history and eventuates in conclusions that are checkable by history.

If he was willing and able to slip free of reality at a moment of extreme historical urgency, it is hardly surprising that he chooses to do so when he is under no such pressure. Few of those who read The Childhood of Jesus are likely to be surprised to find that, when we enter a place called Laguna Verde, it will have no lagoon, never mind a green one. Between words and things there is always, in Coetzee, a distance.

Advertisement

Nor is it surprising that the characters appear as figments of the narrative rather than as fleshed-out individuals. Their flatness, their lack of psychological depth or telling detail, does not necessarily matter in a story that makes no claims to realism. The Childhood of Jesus is a fable. (“What is a fable?” asks David. “A story from the old days that isn’t true any more,” answers Inés.) Such stories generate their own rules. But a successful fable meets two demands. It must be internally consistent. And the author must keep faith with it, must retain an air of utter conviction about the “reality” he creates. This is the author’s side of the bargain if the reader, in turn, is to “submit to what is written on the page.”

Neither of these conditions is fully complied with in The Childhood of Jesus. Early on, Simón is told by the foreman Álvaro that he should not despair in his struggle to learn Spanish: “Don’t worry, persist. One day it will cease to feel like a language, it will become the way things are.” This is an excellent description of what it feels like to read a successful fable: we begin by feeling lost and disoriented but the author’s own certainty makes us accept that what is on the page is the way things are—in this parallel universe at least. Here, that transition does not happen.

One of the difficulties is that the novel’s inner world does not quite cohere. In Here and Now, Coetzee accepts what he calls “the weak Nabokovian thesis” about the construction of fictional realities: “that the novelist should not provide internally contradictory data (a carpet that is red on one page and blue on another).” Sometimes, The Childhood of Jesus crosses the line between the passive withholding of basic data from the reader and the active provision of contradictory data. For example, in chapter 2, Simón does not seem to know what age he is: “He does not feel of any particular age. He feels ageless, if that is possible.” But in chapter 24, he looks back to this same time and recalls that, far from feeling ageless, he was piqued because his new identity card recorded him as being forty-five: “he had felt himself to be younger.” How could he have simultaneously felt himself to be ageless and felt himself to be younger than forty-five?

The inhabitants of Novilla seem to have a complete belief in the afterlife and therefore a relaxed attitude toward death. “If he died,” explains Inés of a sailor who has been in an accident at the docks, “he will go on to the next life. So there is no need to be worried about him.” Why, then, does Álvaro make frantic efforts to save the same sailor? The loss of David’s letter to his mother is referred to often as an important point in the narrative. But why should it matter in a world where all memories and past entanglements have been excised? We have learned early in the novel that there is, in any case, no mechanism in Novilla for reuniting sundered family members.

Simón is said to be struggling with the new language he has to learn and gives vent to his deep frustration at his inability to express himself:

What do you think I am doing in this country where I know no one, where I cannot express my heart’s feelings because all human relations have to be conducted in beginner’s Spanish?

Yet both before and after this outburst we find him discussing very complex things in this supposedly rudimentary Spanish. We have just heard him use, in properly formed sentences, abstract words like “animosity,” “prejudice,” “materialize,” “destiny,” “intuition,” “intimidated.” Within three pages we are told that he engages in regular “philosophical disputation” with his workmates. This includes daily lunchtime discussion of “truth and appearance, right and wrong.” (No baseball arguments or blue jokes for these stout proletarians.) A few pages later, one of those workmen is referring to him (without irony—the Novillans don’t do irony) as “our eloquent friend.”

These problems of internal consistency are made more disconcerting by the feeling that Coetzee lacks confidence in the universe he has created. In order to accept what is on the page, the reader must feel that the author does likewise. But a sense of authorial anxiety hangs over The Childhood of Jesus like a rain cloud dark with second guesses. The fabulist’s proper answer to the question “Why is this like this?” is that given by Simón to David: “Because that is the way the world is.” The fabulist should never apologize and never explain. Here, Coetzee worries at his invented world. He seems at times to be caught between the bold assertion of its fictive reality and a guilty urge to provide mental footnotes.

The reader will wonder, for example, why all the grain that arrives at the Novilla docks is unloaded by hand, sack by sack, even though we are in an era of mechanization. But the reader will get over this doubt—if the author does. Coetzee, however, chews doggedly on the problem, to the extent of having the stevedores conduct a formal debate on whether or not they should use cranes. They don’t seem to realize that the reason they do not use cranes is because Coetzee decided that they shouldn’t.

Improbabilities are boldly presented, then nervously apologized for. Álvaro, when we first meet him, is the most astonishingly sweet boss of a laboring crew in literary history. He even takes care of David while Simón is working and gives his new, unknown employee money from his own pocket. Then authorial anxiety creeps in and Coetzee whispers: “not what you would expect from a foreman.” Yet the other stevedores don’t ask Simón anything about himself or the boy. Coetzee feels it necessary to tell us that this is because they are “strangely incurious.” (Why should this be strange in a purely invented reality, where people do not behave as we expect them to?)

When Álvaro uses the phrase “the urgings of the heart,” Coetzee is again struck by the incongruity of the words he has just written: “Who would have thought Álvaro had it in him to talk like that?” It is not enough that Simón should ask himself questions about the meaning of it all, he has to ask himself questions about why he is indulging in this self-interrogation:

Why is he continually asking himself questions instead of just living, like everyone else? Is it all part of a far too tardy transition from the old and comfortable (the personal) to the new and unsettling (the universal)?

This lack of conviction puts rare pressure on Coetzee’s style. Most of the book is written in the clean, spare prose that makes him such a pleasure to read. But there are some oddly clumsy sentences here: “Dressed in boots and overcoat, he has never seen her behave so imperiously before.” Odd eighteenth-century exclamations pop in from nowhere: “pray tell me”; “what a pity!”; “behold!”; “my boy.” And the exaggerated flatness of the dialogue verges at times on the parodic. Ana, a young woman with whom Simón wants to sleep, is as much puzzled as repelled by the idea. She sounds, in her robotic incomprehension of human foibles, like the half-Vulcan Mr. Spock in an early episode of Star Trek: “You want to grip me tight and push part of your body into me. As a tribute, you claim. I am baffled.” This is hardly what Coetzee had in mind when he wrote to Auster of an austere late style, stripped of the “poetry of language.” Or, if it is, that poetry would not seem so contemptible after all.

Yet the lack of faith in his invented world that leaves The Childhood of Jesus so underpowered is actually good news. For if the novel fails to function as a fable of any great potency, it does have its own drama: the playing-out of a great novelist’s argument with himself about where he wants to go next. In its general form, the novel can be seen as a kind of fantasy of artistic escape—from poetry, from the seductions of storytelling, from memory, from place, from the past. It is a blank slate gradually filled with whatever marks Coetzee feels like making. But the anxiety that hovers over the book also serves as an attack on this very fantasy. It suggests that Coetzee, in spite of himself, is not content to sail off into a late style of fiction filled with figments of pure imagination who debate abstract “questions of life and death.”

Novilla, in a sense, is what Coetzee’s fiction would have been like had he written in zero gravity, had he in fact been free of human, political, and historical entanglements. It is a pale, amnesiac utopia. Its people have left messy existence behind and sailed into a new life of stripped-down simplicity. They are free of the deadliest sins: lust (sex seems purely functional); greed (everything is cheap and there is nothing much to buy anyway); gluttony (food in Novilla is dull, basic, and paltry); anger (they are for the most part remarkably placid); ambition (the dockers are content with their back-breaking labor); shame (there are no memories to haunt the conscience). There is no history: one of the philosophical stevedores says that “history is not real…history is just a made-up story.” There are no politics—even the radio has no news bulletins. And there is no subtext—everything seems to operate on the surface; people say what they think.

It is rather good to know that Coetzee can’t give himself entirely to such a story, that he is not at all convinced by the anodyne utopia he has created. Simón perhaps speaks for him when he asks, in a moment of anguish, “What is the good of a new life if we are not transformed by it, transfigured, as I certainly am not?” He is an astute critic of the world Coetzee has invented for him, noting that “things do not have their due weight here”—the precise definition of the difficulty with a novel in which anything can happen and, therefore, nothing that happens can mean very much.

Perhaps the truth is that Coetzee can’t really have a late style, for the simple reason that he developed his late style quite early. The stripped-down, unornamented prose, the impatience with narrative seduction, the desire to evoke big questions of human existence, the move from the particular to the universal—these are surely attributes not of books that Coetzee might write in the future but of those he has already written. Those books do not turn their back on the world—in his own words, they rival it, in all its personal and public entanglements. The anxiety that haunts The Childhood of Jesus suggests that Coetzee cannot escape comfortably into aridity, that he is too alive for posthumous writing, that he is doomed to go on being one of reality’s greatest rivals.

This Issue

September 26, 2013

The American Jewish Cocoon

They’re Taking Over!

Stranglehold on Washington

-

*

Paul Auster and J.M. Coetzee, Here and Now: Letters, 2008–2011 (Viking, 2013). ↩