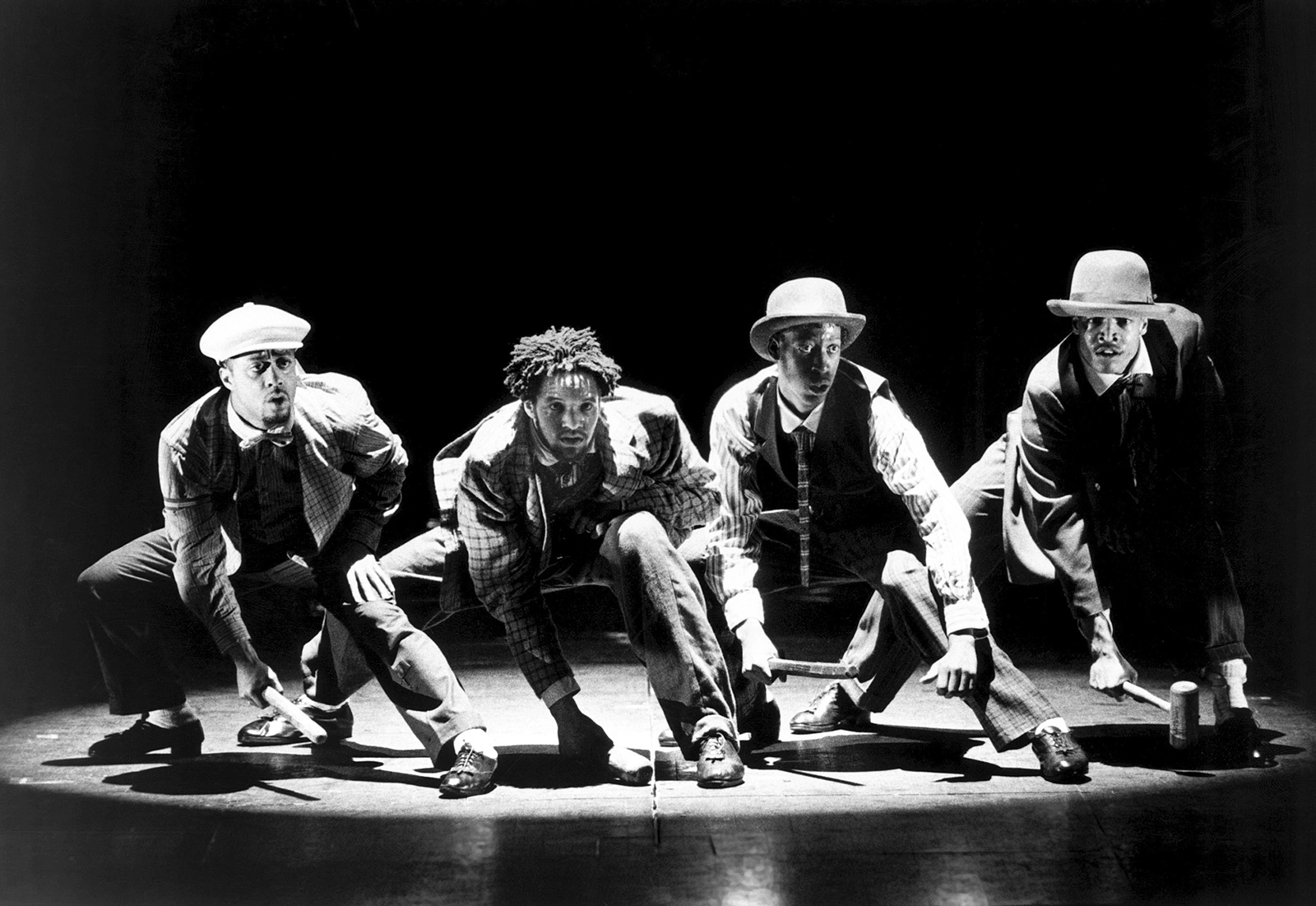

Probably the first dance anyone ever did was a tap dance. Beating the feet on the ground was elementary communication; doing it in time was a pleasure. The tribal dances of sub-Saharan Africa amazed Europeans with their rhythmic exactness as long ago as the eleventh century. The dancing was monitored by the beating of drums, a practice that survives in modern-day performances in which dancer and drummer exchange signals and rhythms. In these purely percussive conversations the art has its most refined, most radical expression. I once watched Baby Laurence for nearly twenty minutes dance deeper and deeper into literally radical territory. Between the dancer and the drummer, the human root of jazz lay exposed.

There is no one tap dance style. Idiom feeds on idiosyncrasy. In live tap dance performances the sonic experience is more various and discursive and often more alluring than the optical one. This is the theme of Brian Seibert’s What the Eye Hears, the first authoritative book on the subject since Marshall and Jean Stearns published their classic study Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance in 1968. Seibert is far less concerned with the legitimacy of the art than the Stearnses, far more disposed to interrogate it. He doesn’t take up the story where they left off; he begins where they began, in Africa. It is a remarkable story no matter how often it is told, and it is an American story.

American tap dance had another point of origin besides Africa. In the British Isles, wooden clogs could make gratifying noises. According to the oral history quoted by Seibert, during the industrial revolution millworkers rattled their feet to the beat of machinery “and were pleased by the sound. During breaks, they held competitions on the cobblestones, folding in jigs and morris dances.” The African drum dance began to merge with the hornpipe, the Irish jig, and the Lancashire clog on the way to America.

The passage was through the lowest social strata; Irish POWs were deported by the British in the tens of thousands to the Caribbean or to Virginia, and on the slave ships, Seibert writes, “on those cursed vessels, on those wooden decks, English and Irish ways of dancing met African ones.” British slave owners outnumbered other nationalities in the colonies, and inevitably slaves and slave masters mingled, compared traditions, and shared steps. Though the question of who borrowed what from whom can still start arguments, it doesn’t interest Seibert as much as the way the borrowings were changed. But this, too, is impossible to trace with certainty when whites were imitating blacks who were imitating, or satirizing, whites. The white imitations—of black music and dance, black behavior, black humor—coalesced in the blackface minstrel show.

The institution of blackface minstrelsy lasted more than a hundred years, with thousands of troupes playing all over the country and touring abroad. Another level of ambiguity was added with black blackface minstrelsy. Negro performers painted their faces blacker and added the full red lips and wool wigs of the standard minstrel mask. And a mask may have been all it was. After seeing a performance by black minstrels in 1849, Frederick Douglass wrote that they “had recourse to the burnt cork and lamp black, the better to express their characters, and to produce uniformity of complexion.”

If minstrelsy was, as James Weldon Johnson declared, the “only completely original contribution America has made to the theater,” how much more original was black minstrelsy? Authenticity was its great selling point, and the public, white as well as black, was eager to buy, because the black minstrels were not only the real thing but, it was generally agreed, much better than the whites. That aside, questions remain. Although Seibert is not primarily a social historian, he is bound to consider the convolutions beneath the surface:

That the [white] imitators altered the dances can be presumed, but with what mix of mimicry and mockery, distortion and invention? The questions are important, because it was through minstrelsy that the dances called jigs, juba, shuffles, and breakdowns became theater. It was through minstrelsy that they became tap.

The dance called “cakewalk” was a step dance, not tap; its showoffy signature step—prancing with the legs kicking up and out—made it a perfect vehicle for social attitudinizing both satirical and straight by partygoers both black and white. Danced in groups traveling in a circle, it was a kind of American counterpart to the European polonaise—a picture of society enjoying itself. Megan Pugh analyzes the cakewalk fantasy as she does all of the subjects of America Dancing, in depth and detail. What she says about cakewalking typifies her own approach to dance history: “In the puffed-up chest of the imagined dandy, the circular path of society on parade, layers of admiration and satire pile on top of one another like sediments from geological eras.”

Advertisement

Pugh’s layers pile dance on top of literary, social, and cultural criticism. This works in some cases to illuminate a dance that is already concerned with things outside its own life, but it is less effectively used on self-referential choreography created between the 1950s and 1980s, the most intensively hermetic period in dance history. Pugh’s “outing” of Paul Taylor’s Esplanade (1975) is based on his presumed antipathy to ballet, but her suggestion that Taylor is “picking a fight” with the opening sequence of George Balanchine’s Serenade hasn’t far to go when one considers Taylor’s choice of music, which includes Bach’s Double Violin Concerto, the same music Balanchine used for another masterwork. If Taylor is picking a fight, surely it’s with Concerto Barocco. As for the cakewalk, Pugh again leaves off the topmost layer of her critique in her readiness to provide novel, not to say preposterous, interpretations. Her view of the cakewalk is of a dance literally haunted by the use to which it was put in a fictional newspaper story of 1907 about skeleton ghosts rising out of their graves and dancing. For Pugh, the historic cakewalk, conditioned by the graveyard cakewalk, is thus “tied inextricably to [the Civil War’s] national traumas,” whereas for any other fanciful dance historian it is tied to the second act of Giselle.

Like all researchers in popular dance, Seibert and Pugh have had to face a major historiographical block, namely the lack of connections with music. While some of the steps and figures of various dances and dance genres made it into the archives, until the advent of sound recording almost no documentation existed for the changes in rhythm that drove them. A crucial change was the moment of syncopation. By the 1890s, when ragtime made the cakewalk a national fad, the place of jazz in American life was made, but when and how the ragged rhythm affected tap dancing can only be guessed. We have the word of a prosperous white dancer, James McIntyre, who claimed to have introduced the syncopated buck-and-wing to New York in 1876, but who when queried admitted that he had watched southern Negroes “soon after the Civil War.”

The dearth of musical evidence may be the reason that, although African-American dance artistry and musicianship have long been celebrated, the precise evolution of tap dancing as an art form and of tap dancers as distinctive artists is not often attempted by historians. Seibert’s achievement in What the Eye Hears is to sustain intense concentration on the purity and beauty of tap dancing without falling into preciousness, obscurity, or pedanticism, or scanting tap’s social and political setting.

The aesthetics existed within a total picture of degradation. The fact that our most derisive and long-standing racial epithets stemmed from songs and dances—“Jump Jim Crow,” “Zip Coon,” “Nigger Jig”—is only one facet of a complex, perversely paradoxical epoch. Take the conundrum of blacks in blackface, which to Seibert “transcends irony”: Was it self-caricature or the means by which to compete with white performers? If to audiences the selling point of black minstrelsy was authenticity, to the performers it may have been competition. Seibert looks for a link between the gradual relinquishing of what seems an odious custom and the growing self-esteem of black dancers as theater artists. From being a sport—seeing who could dance longest without spilling a drop from the glass of beer on his head—dance became a high-toned exhibition of technique. Competition became the keynote of an art.

Seeing who could produce the most novel, most difficult, most musically adroit step or combination of steps was good; hearing a unique sound was great. It was all by way of attaining the ultimate goal, individuality. Why was this so important? My guess is that asserting one’s personal identity in an elegant manner was the best defense against racism, the best rebuke to the insult of racism, which is an insult of generalization. “Make it yours” was the challenge put by dancemaster to disciple. Be yourself, make your own sound.

It was the mandate of a tradition. In the old “dancing cellars,” judges sat under the stage, listening. The medium gained a consciousness around the time that manufactured metal taps replaced pennies stuck into boots. There were no classes, no schools of tap dance. For generations, hoofers gathered in cafés, barrooms, wherever there was a back room with a piano, or just on the sidewalk, to trade, teach, and top each other’s steps. The famous Harlem dance fraternities—the Hoofers, the Copasetics—were formed to preserve a tradition. Being in the line of succession meant developing a recognizable personal sound; otherwise there would be no tradition worth preserving.

Advertisement

There is no indication in the books by Seibert, Pugh, or the Stearnses that these unrelentingly scrupulous dancers were aware of the political implications of selfhood. It may not be irrelevant that the authors of these books are all white. James Baldwin’s words are to the point: “I was not born to be what someone said I was. I was not born to be defined by someone else, but by myself, and myself only.” If there was in fact a transition from antiracism to straight self-expression, it must have been entirely natural, as natural as tap dancing itself. By the 1920s, the Golden Age of tap, the great dancers had become headliners in vaudeville with the means to a secure living and a direct route to Broadway. Show business was still segregated, but by the time Jazz Dance was written in the midst of the civil rights gains of the 1960s, there may not have been such a pressing need to defy racism—at least not for tap-dancing poets. As a political imperative individualism was fading. Tap dancing was becoming purefied modern art.

Brian Seibert is a dance critic known for the penetration and nimble wit of his reviews, mostly for The New York Times. A tap dancer since the age of six, he writes history for the nonspecialist reader in the kind of casual, hip language one would wish and might logically expect to encounter today in a work of this kind. Nearly half a century ago, when jazz enthusiasts were still evident in our culture, Marshall Stearns wrote about the art he loved, but he did so in the impersonal prose of the trained academic. A medievalist who taught English at Hunter College, he played tenor sax and was a founder of the Newport Jazz Festival and the Institute of Jazz Studies. He wrote in celebration, implicitly challenging the inability of white liberals to think of black artists in any but political terms, and the inability of whites in general to think of tap dancing as an art.

Seibert is more personally engaged, more sensuously involved with performers and their special skills, and his writing, not I think coincidentally, has a rhythm and a voice. Into this book, his first, he pours enough information for six others, and in dazzling displays of erudition sometimes seems more professorial than Stearns. Half a dozen definitions each are given for juba and buck, as in buck dancing. (Juba, the more amorphous term, can mean a type of dance, a dance performance, a dancer or dancers known as Master Juba, or the entire black tap dance tradition, especially in minstrelsy.) Etymologies are traced for the name Bojangles; a genealogical link is found between the pioneer T.D. Rice, “the best white black man in existence,” who danced as Jim Crow, and Fred Astaire entertaining the ship’s black crew a whole century later in Shall We Dance.

Seibert writes about Jazz Dance, without which his own book “would be immeasurably diminished.” The legacy of Marshall Stearns is evident in What the Eye Hears, not only in Seibert’s commitment but in his subject, taking in the subsequent revival of tap by a generation possessed by the revelations of Jazz Dance. Stearns never wrote a sequel; he died as his book was going to press, and it was finished by his wife Jean, a jazz authority in her own right.

Jazz Dance is still very well worth reading.* Based on dozens of interviews, it deals mostly with the lives and careers of Harland Dixon, John Bubbles, Willie Covan, Eddie Rector, Fayard and Harold Nicholas, Honi Coles, Cholly Atkins, Pete Nugent, Chuck Green, and Bunny Briggs. In the 1950s and 1960s, they were aging and partially forgotten men, yet most were still vigorous performers. And they had good memories (though with a tendency, Seibert notes ruefully, to forget dates). Stearns rescued them from obscurity, first in a historic presentation in 1962 at the Newport Jazz Festival, then in his book.

As one reads these two indispensable books, they come to seem like father-and-son works, rooted in their respective eras. Seibert notes Stearns’s insistence on masculinity in tap vs. effeminacy in ballet, his nostalgia for big-band swing, and lack of interest in bebop (it wasn’t undanceable; you just had to be Baby Laurence), in female dancers, and in all Hollywood musicals except Astaire’s. Seibert is schooled in movie and TV history, multiculturalism, internationalism, postmodernism and post-postmodernism, and gender equality. His dance idol, Jimmy Slyde, and his first tap mentor, Buster Brown, aren’t in Jazz Dance; in What the Eye Hears Slyde is a patriarch, and Brown is tutoring post-postmodernists.

Tap is traditionally a soloist’s art, with duos to stiffen the challenge of competition and to give one dancer a rest while the other performs. It is not spatially assertive; it doesn’t require sets. In the 1940s, tap dance vanished from Broadway and Hollywood only to reemerge on television, which ought to have been its ideal medium. But the networks could not produce it. Guest-star slots on variety shows were all they could provide, and technical problems—the floors, the sound—were never solved. Competitive dancing was out because it depended on improvisation; fixed formats placated the studio technicians and misrepresented the art.

That was also the problem with the movies. Bill Robinson got the exposure he deserved in the movies; John Bubbles didn’t. Part of the reason was that Bubbles had to improvise, and he and his partner were comics. In film appearances Buck and Bubbles are barely getting going before their number ends. According to Seibert, the only dancer to have improvised in a Hollywood film was Steve Condos in a 1949 short, trading phrases with the drummer Buddy Rich.

On Hollywood, Seibert is a fine companion in the screening room, seeing what you see and more. He reviews, probably for the first time, the dancing of Hal LeRoy, James Cagney, Ruby Keeler, Mickey Rooney, Donald O’Connor, and a few dozen others. But the story of tap dancing in the movies will always, it seems, be shared between Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly. I tend to think, no doubt simplistically, of Astaire as descending from the black jazz tradition and Kelly from the Irish one. For Seibert the integrity of filmed tap dance is the real issue. As a tap dancer, Gene Kelly was “the lightweight.” He “didn’t advance the art of tap on film so much as preside over its eclipse.”

Unlike Astaire, Kelly didn’t always dub his own taps. But is using Kelly’s solo in “Singin’ in the Rain” as an example of movie fakery—“what the ear hears isn’t always what the eye sees”—really fair? Is truth in tapping such a virtue when most of the taps are splashes? Seibert points out the irony in the fact that the plot of Singin’ in the Rain is about dubbing. He makes a much better point about the logic of Sun Valley Serenade. Hollywood’s racial policies in 1941 allowed African-Americans to perform numbers but denied them roles in the story, and they made up excuses for doing it. In Sun Valley Seranade, Dorothy Dandridge and the Nicholas Brothers appear out of nowhere and perform the film’s big number, “Chattanooga Choo Choo.” Then, Seibert writes,

once their number’s finished, they vanish. That was their role, you might say—tap dancers and singers, not actors. But [the star] Sonja Henie was no actor, and the brothers provide the best three minutes in the film.

I might add that the presence of the beautiful Dandridge leads you to want more of her, both in the story and in the dance—and not just because, in real life, she married Harold Nicholas.

The 1940s though the 1970s, the years Seibert calls “The Great Recession,” ended with a shakeup emanating from the tornado of the sexual revolution. Tap had always been a predominately male profession. Stearns’s rediscovery of the Harlem virtuosos brought a phalanx of women to Off Broadway showcases, launching what some saw as an overdue bid for equality and others as little more than a ladies’ auxiliary of tap—what Seibert calls a “sorority Copasetics.” The women attached themselves to the old masters as sponsors and trainees, and brought them downtown for what one of them, the irrepressible Sandman Sims, called “a last hooray.” They built up an audience for their teachers and models. They succeeded less well in attracting an audience for themselves.

At times it was hard to know which cause was being advanced, tap dance or feminism. Women came to dominate the world of tap as they did modern dance. But very few were able to reinvent themselves in the idiom of tap; in Seibert’s opinion, the women of the 1980s danced like men or tried too hard not to. Brenda Bufalino, Jane Goldberg, and others performed a service as advocates and promoters, and they were encouraged in Harlem because they were earnest, hardworking, and smart. Their dancing didn’t please the majority of the elders, not because they were women but because they were white and gravitated more naturally to modern dance traditions than to jazz. They taught their companies to perform syncopated complex ensemble choreography but, in Seibert’s words, “it would be hard to say that seeing [Gregory] Hines’s steps done in unison by five women of middling stage presence constituted an advance in the art.”

Tap dancing returned to Broadway in the commodified but pleasant form it had customarily enjoyed there before the ballet boom erased it. Shows like No, No, Nanette (“the new 1925 musical”), 42nd Street, and Tommy Tune’s My One and Only were hits. The other world of tap appeared in a handsomely mounted revue called Black and Blue: it had Jimmy Slyde, Bunny Briggs, and an amazing sixteen-year-old, Savion Glover. Glover’s rise, as voluminously described by Seibert, made me wonder why it wasn’t preceded by at least a mention of the evolution of rock. Maybe rock did nothing for tap, but the rock culture bears some responsibility for the bad-boy image Glover went on to cultivate after he wowed Broadway with his own show, Bring in ’da Noise, Bring in ’da Funk. The dance counterpart of rock, though, is not Glover but Michael Flatley, lord of Riverdance, Inc., whose companies dance jigs in a style as physically and rhythmically straitjacketed as it must have been on the slave ships. Seibert abhors it. It is now being taught in some public schools.

Rock and Motown are addressed by Pugh in her essay on Michael Jackson. In scope and emphasis Seibert’s and Pugh’s books are almost mirror opposites. He seems uncomfortable with anything that isn’t tap; she seems determined to rule out anything that isn’t profoundly American. With Bill Robinson, the Astaire–Rogers movies, Agnes de Mille, Paul Taylor, and Jackson as focal points “celebrated for embodying the country in movement,” she presents an array of genres and eras apparently designed to bring dance into the discussion started seventy-five years ago by the cultural historian Constance Rourke, which may be a fitting objective now that dance scholarship is attracting the attention of the academy.

Although Pugh has held academic posts, her metier is really writing. What saved her book for me was the obvious pleasure she got out of writing it. It is full of genuine insights that must contend with a tendency to get carried away, to let imagination overwhelm disciplined narration. Data as well as interpretations are overdone. Perhaps the problem is that so much of her book is written from video. After multiple viewings, a performance becomes rigid and the viewer may overinterpret. Seibert in his summing-up observes that for the young now becoming dancers and (I presume also) dance scholars, “what history mostly means…is footage: the compilations of video clips from movies, TV variety shows, documentaries, and concerts…. This is their repertory. This is their usable past.” In other words, YouTube is unavoidable.

Seibert risks turning the final quarter of his book into a virtual encyclopedia of trivia. So far as tap was concerned, the twentieth century—the century of dance—went out with a bang, and Seibert ends with the current wave of international tap stars too many of us have never seen. But not before his chronicle of the declining years, when an art form in its dotage proved that it could suddenly be redirected toward innovation and experimentation.

The wholesale revision of the art and spectacle of tap dancing in recent decades has been attributed to Glover’s leadership, and some observers have seen in it the transformative rebirth that the world of tap was waiting for. Glover is now forty-two years old and about due for a Kennedy Center honor. Seibert sees him as an ambivalent figure, a rebel with a conscience, drawn to mixed musical modes like “reggae-inflected hip-hop, rap-injected R&B,” but also as a richly talented dancer whose connection to tradition can’t be denied. When I go to look him up on YouTube, I’m invariably also moved to run the film of his ancestor Bill Robinson doing his stair dance, “the most famous single act in tap-dance history.”

In Bring in ’da Noise, Robinson was caricatured as “Uncle Huck-a-Buck,” a black lackey catering to a giant Shirley Temple doll. That was the way the African-American press portrayed Robinson in his lifetime, and it may be how he is still seen in some parts of the black community. But for the theater sophisticates who produced Glover’s show in 1995 it was all there was to know about Robinson; as Seibert writes, “the show’s satire was far too snide and self-righteous.”

On YouTube, Robinson is seen in two slightly different clips from the early 1930s. Sound is deliberately belied by sight. Robinson’s erect posture does not so much exploit gravity as defy reason. How can he remain so still, how can so many different delicate sounds be made by a pair of wooden soles that stay close together and spring apart, letting in a burst of silence before the music resumes. At certain moments only the shuddering of his pants leg betrays the source of those bewitching sounds.

This Issue

February 25, 2016

The Psychologists Take Power

A New Deal for Europe

TV: The Shame of Wisconsin

-

*

Jazz Dance was reissued in 1994 by Da Capo, with a foreword and afterword by Brenda Bufalino. ↩