It is a publishing phenomenon, for which some of us who are authors have cause to be grateful, that seventy years after the conclusion of World War II, works about the conflict enjoy a popularity second only to cookbooks. This is unsurprising, because it was the greatest event in human history, a saga that offers narratives about a collision between the forces of good and evil much less nuanced—apparently so, at least, to unsophisticated readers—than the modern struggle between militant Islam and the West.

New publications fall into disparate categories. The first is that of sentimental, shamelessly nationalistic titles such as The Greatest Generation (2004) and Flags of Our Fathers (2000), which achieve huge sales but contribute little to historiography. I recall a US Army veteran saying about Stephen Ambrose’s books—superior contributions of this kind—“They make people like me feel real good about themselves.” The late Russell Weigley, author of Eisenhower’s Lieutenants, the excellent 1981 study of the northwest Europe campaign, once observed: “Steve took to raising monuments rather than writing history.” There seems nothing wrong with flag-waving books, so long as we recognize them for what they are.

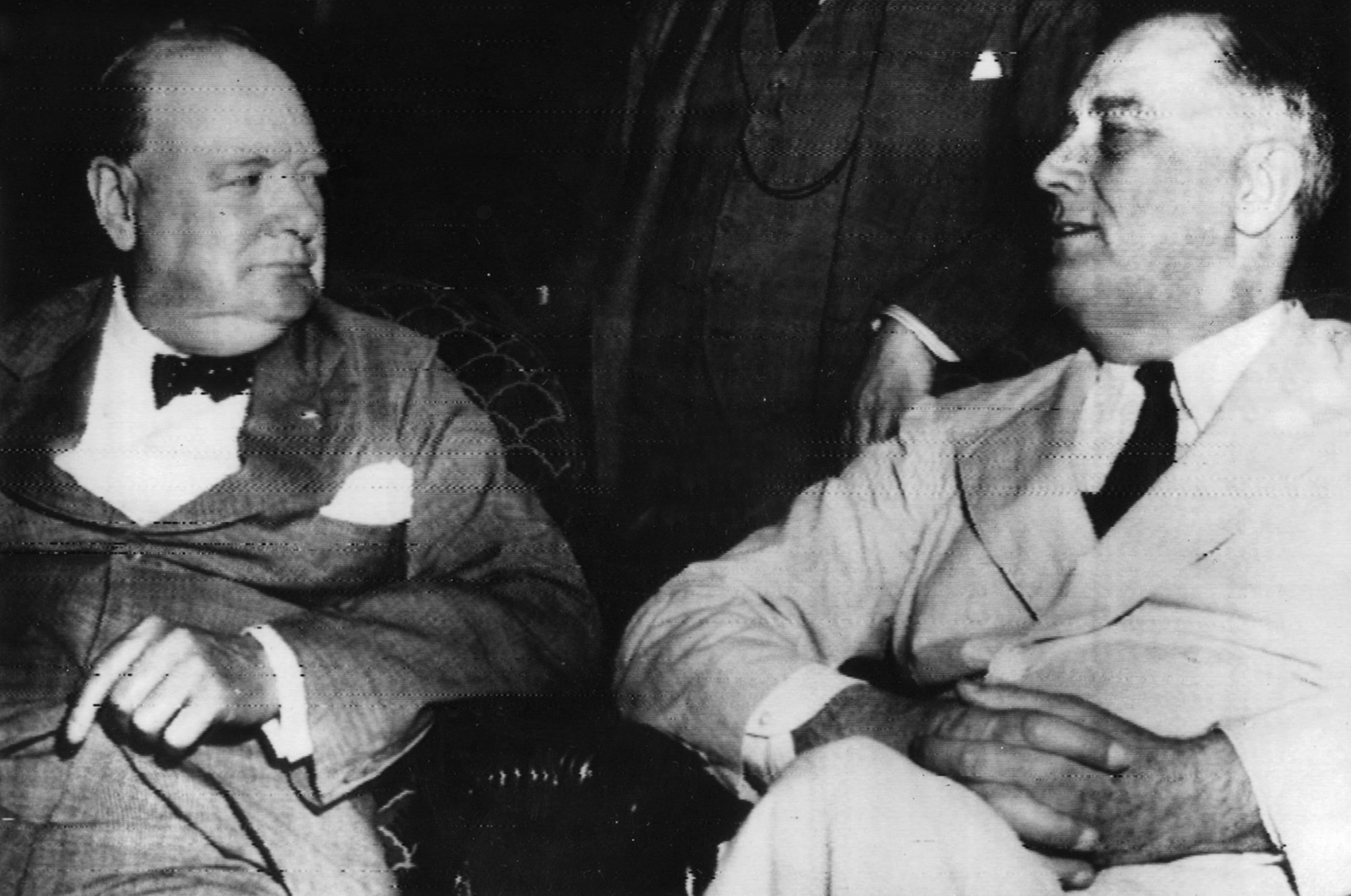

It is a perennially fascinating question for authors, publishers, and readers, how often the same story can be retold. My first London agent, Graham Watson, in his day the doyen of his trade, said to me back in 1969: “Every biography and history can be reprised every ten years.” Nowadays, the cycle is much shorter than that. Robin Prior’s When Britain Saved the West is a stirring retelling of the saga of 1940, emphasizing the centrality of Winston Churchill, without whom it is likely that any alternative British leader would have parleyed with Hitler. The author is fiercely critical of Franklin Roosevelt, arguing that the US president was “resolute for inaction”; he emphasizes the harsh cash-and-carry terms on which America supplied arms to Britain. Prior is an academic based at Flinders University in South Australia who writes vividly and well.

So does Niall Barr, author of Eisenhower’s Armies, a study of the Anglo-American military relationship in World War II. The author, who teaches war studies at King’s College London, devotes his early chapters to the historic relationship of the British and American armies, first in the Revolutionary War, then in World War I. The central theme of his book, however, is the manner in which a synergy evolved between the two Allied military establishments between 1942 and 1945. Inter-Allied relationships were remarkably good at the operational level, among soldiers and staff officers. Barr argues that historians have focused too much attention on the notorious quarrels between generals, and not enough on the towering fact that the Allies won.

He is surely right about this, and right to say that no other wartime alliance has worked half as well. But it seems hard to ignore some realities about the relationship, unpalatable to Atlanticist romantics. The three major powers in the Grand Alliance fought World War II for diverse reasons, with profoundly different visions of the postwar world to which they aspired.

As the struggle progressed, and when victory became assured, the US asserted its dominance over Britain in an ever more ruthless fashion. This caused distress to Churchill’s people, high and low, which at the time it was expedient to conceal. At the bottom of the system, it was manifested by the British private soldier occupying a slit trench in Normandy who shouted bitterly to a column of GIs, newly arrived from England: “How’s my wife?”

As for relations at the top, some of Churchill’s biographers, including Roy Jenkins and me, believe that the prime minister’s absence from Roosevelt’s funeral was dictated not by duties of state, as he himself claimed in April 1945, but instead by anger about the perceived slights and injuries inflicted by the president during his last years in the White House.

Neither Barr nor Prior tell us much that we did not know already. A good case can be made that The Struggle for Europe—the Australian Chester Wilmot’s 1952 account of the conflict—was so authoritative, not least in its harsh judgments on the limitations of the Allied armies, that every subsequent author has merely followed in his footprints. But each generation likes to chronicle the old story anew: Barr and Prior do this well enough, with plentiful contemporary anecdotage.

There has been only one important factual revelation about the war since Wilmot’s work appeared: the brilliant Allied codebreaking operations, the so-called Ultra Secret. It was acknowledged in 1946 that the US had broken the Japanese Purple diplomatic cipher, but only in 1974 was the scale of British penetration of Germany’s Enigma coding system revealed. This disclosure made necessary a review of the entire narrative of the struggle, especially those elements concerning the war at sea.

Advertisement

The outcome, however, was that over the ensuing decades many books exaggerated the role of Ultra, treating it as if it had been a war-winner in its own right. I argue instead in my own new book about 1939–1945 intelligence, The Secret War, that it is critical to recognize that knowing the enemy’s hand did not diminish its strength. Moreover, far from Ultra providing the Allies with comprehensive access to German and Japanese signal traffic, the picture was always patchy and decryption of many enemy keys was subject to delays.

As late as September 1944 Bletchley Park read only 18 percent of German army traffic. What was done by the codebreakers was indeed miraculous, but they could not walk upon all the water all the time. A nuanced interpretation suggests that even such excellent intelligence as was secured by the Western Allies did little to diminish the operational difficulties of defeating the Wehrmacht, although it played a critical part in overcoming the U-boat.

Even though game-changing novelties have been lacking for many years, there is almost infinite scope for new interpretations and perspectives. Two recent studies seem especially worthy of attention, one for the general reader and the other for specialists. The former is the work of Antony Beevor, who has become one of the most respected, as well as globally popular, chroniclers of the struggle.

He made his reputation with Stalingrad (1998), which used previously inaccessible Russian sources to lay bare the unspeakable brutality of the Eastern war. There is a delusion, widely held in Europe and the US, that World War I was qualitatively the most ghastly military experience to which soldiers have ever been exposed. In truth, while numerically the losses were the most grievous in the French and British experience, what was done to men at the Somme and Passchendaele was no more ghastly than the fate of victims of the Thirty Years’ War, Napoleon’s campaign in Russia, the US Civil War—or the 1941–1945 Eastern Front. No recent writer has done more than Beevor to focus attention on the magnitude of the Russo-German struggle, which must properly dominate the military narrative of World War II.

His latest book, an account of “Hitler’s last gamble” in the Ardennes in December 1944—when German forces mounted a large-scale and unforseen attack on Allied forces in northern France—combines in his usual masterly fashion the big picture with shellhole-level anecdote. Beevor’s books have hitherto gained less celebrity and sales success in the US than they deserve, but Ardennes 1944 may be the one to change that. So much mediocre work is still produced about the war, and especially about the Western Front, that a book that tells in vivid prose the story of a great battle, accompanied by impeccable judgments, deserves celebration.

The author offers a droll postscript observation to his account of the American triumph that followed American humiliation: “The Ardennes campaign produced a political defeat for the British.” Montgomery’s arrogance in publicly demanding credit for saving Eisenhower’s armies “stoked a rampant Anglophobia in the United States and especially among senior American officers in Europe…. The country’s influence in Allied councils was at an end.” Beevor suggests that Eisenhower’s fury about British conduct, though veiled at the time, influenced his brutal response to perceived British perfidy in 1956, when as US president he pulled the plug on the Suez invasion.

Alan Allport’s Browned Off and Bloody-Minded is a sociological dissection of wartime attitudes within the British army, which demonstrates that a diligent and imaginative historian can still make an original contribution to our understanding of the period. The army was the least impressive of Britain’s three services (as indeed was also the case with the US Army). Even on a good day Churchill’s generals rarely surpassed adequacy.

Soldiers on the battlefield sometimes displayed stolid courage and fortitude, but seldom much professional flair. They were uniformed citizens, performing an unwelcome duty in the name of king and country. Many were embittered to find Britain’s class system institutionalized in khaki: the disparity between the respective rations and living conditions of officers and men behind the front was unworthy of a modern democracy.

Some of their own commanders were privately nasty about the troops. General Noel Irwin wrote from Burma in 1943 that his men “practically without exception are not worth 50 percent of Jap infantrymen in jungle country.” Meanwhile, many rankers had no higher opinion of their leaders. The book by Allport, a British-born assistant professor at Syracuse, reflects impressively wide reading, and commands respect for its shrewd judgments and lack of sentimentality. In 1944–1945 the British army became just, but only just, good enough to have an effective part in the Allied march to victory.

Advertisement

Another genre of books seeks to highlight hitherto unrecognized individuals, units, or theaters of war, almost always spuriously. There should be a statutory ban on use of the word “hero” in titles and most texts, because it is so often abused. Linda Hervieux seeks to elevate to unknown hero status an African-American US Army barrage balloon unit that landed on Omaha Beach on D-Day. Yet few serious historians confer such an accolade on support troops, who generally incurred risks and casualties far smaller than those of rifle companies. There is a good argument for acknowledging that African-Americans, and for that matter women, had much more prominent parts in the war, often as victims, than most writers gave them credit for in the past; their subordination was deplorable and should be fully described. Historians, however, should beware of inflating their contributions in order to serve twenty-first-century purposes.

The cartoon and picture book Omaha Beach on D-Day is an example of the toys-for-boys approach to commemorating the war, in this case by retelling the story of Magnum photographer Robert Capa in comic strip format, together with reproductions of his famous photographs depicting the American agony on June 6, 1944. This is a French production, well done in its fashion and offering vividly entertaining viewing to an audience juvenile in heart if not in years.

By contrast, it is welcome that there should be reevaluations of the French wartime experience, by the likes of Julian Jackson, Mark Mazower, and now Philip Nord, a professor of modern history at Princeton and author of several works on France. Nord thinks that the 1940 collapse of the French army was by no means inevitable, and urges that the British and Americans should bear a larger share of blame for standing passive amid the rise of Nazism.

He suggests, in his France 1940, that if France’s politicians and generals had possessed the will to launch a major offensive on the Western Front in September and October 1939, when the Germans were preoccupied in Poland, the Allies could have won the war. He rejects the theory of French national moral exhaustion in 1940—what he calls “the decadence story”—instead placing a heavy burden of responsibility on the generals: “Post-revolutionary France was saddled with a military establishment that had not made its peace with democratic institutions and would not so until the 1960s.” This seems a good and important point.

He believes that if the French high command had not deployed its strength overwhelmingly in the north, in anticipation of a rerun of the 1914 Schlieffen Plan, it could have held sufficient reserves in the center to repel the German invasion. He writes: “France’s defeat in 1940 was a military phenomenon, not the inevitable expression of some generalized national malaise or moral deficiency.”

He further asserts that during the subsequent years of German occupation, France experienced a “moral reawakening”: that historians are wrong to emphasize the tiny percentage of Frenchmen who took up arms against the Nazis, but should instead notice the much larger proportion who quietly supported the Resistance, if only by listening to the BBC and not assisting the enemy. I am skeptical about this view. There seems every reason to sympathize with the French people’s acquiescence in the face of military humiliation and occupation, but it is hard to discern evidence of moral regeneration.

There was, instead, a surge of post-war myth-making about resistance, vividly described by Oxford’s Robert Gildea in his impressive recent book Fighters in the Shadows.1 To this day, French scholars are reluctant to explore this period of their national history, leaving much of the important work to American and British researchers, perhaps because both they and their fellow countrymen find the issues so distressing.

Nord’s book reads like an extended lecture or essay. He emphasizes speculation about might-have-beens, rather than offering searching analysis of what did happen, and Ernest May has demolished several of his arguments in his own work Strange Victory (2000). Some of us will continue to believe that the professional superiority of the German army was likely to triumph in 1940, whatever alternative deployments France’s generals had adopted. The overarching reality about Europe in that era is that most propertied people, including generals, were more frightened of Communists than of fascists, and it required a world war to change their minds, for a brief season at least.

Benjamin Jones’s Eisenhower’s Guerrillas is admirably frank in acknowledging the insignificance of the ninety-three joint US–British–French paramilitary teams—called “Jedburghs”—parachuted into France just before and after D-Day. He describes their picaresque experiences, but recognizes that both they and the Resistance groups that they assisted achieved most in regions of least strategic value, notably the wildernesses of the center and south. Many of the German troops used to suppress the July 1944 uprising in the Vercors mountains in southeast France, for instance, would never have been used against the main Anglo-American armies.

Resistance activities in Brittany gave marginal support to the Normandy battle. But Allied leaders, especially Winston Churchill, failed to grasp the difficulties of generating a successful civilian insurgency against a ruthless and heavily armed enemy. The author laments the US failure in Indochina a generation later to understand and learn from the Jedburghs’ shortcomings when seeking to promote special forces and Vietnamese insurgencies. Jones’s sober narrative makes disappointing reading for romantics, but his conclusions are impressively clear-headed.

Yet another branch of Nazi-era literature is formed by Holocaust studies, which in recent years have produced some remarkably original and important works, for instance Timothy Snyder’s Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning2 and Saul Friedländer’s The Years of Extermination: Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1939–1945 (2007). My own reservation is not about such books, but about the manner in which they are often read, without a sense of the larger setting. We know that the Nazis singled out the Jewish people for extermination. But properly to interpret what took place, and especially to understand the responses of Allied political and military leaders to what they learned about the death camps, it seems necessary also to recognize, as Snyder does, the enormity of non-Jewish killings, especially of Russians and Poles, and not least in Auschwitz.

A much less important category of World War II books, though immensely popular, addresses technical aspects of the conflict—aircraft, tanks, small arms, and the like. Unfortunately such accounts usually fail to reflect on both the technical advances that made improved weapons possible and their effects on the outcome of the war, both subjects that are neglected by mainstream historians.

There is now a widespread understanding of the significance of the Allies’ inability to match German tank armament until the last phase of the war, and of the US Navy’s disastrous failures in 1942 and 1943 to use torpedoes effectively, but other important issues are often neglected. For instance, modern US and British readers are so captivated by the brilliance of our forefathers’ codebreaking activities that most are oblivious of the Germans’ successes in the field.

Even in 1945, the Allied armies’ equipment qualitatively outclassed that of the Germans only in their artillery and transport. Elsewhere, the weakness of the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm importantly influenced the war at sea. Inadequate escape facilities from RAF bombers, first highlighted in 1943 by Freeman Dyson, then an operational research scientist at Britain’s Bomber Command, cost the lives of thousands of aircrew.

Posterity takes for granted the gun turret armament of US Army Air Force and Royal Air Force heavy bombers, but both nations might have been better served by using unarmed bombers, which could have flown higher and faster, carrying more fuel and ordnance, without the enormous deadweight of turret guns, which seldom did much harm to the enemy. The British twin-engined Mosquito bomber demonstrated what fast unarmed aircraft could achieve.

Such matters as these exemplify the range of technical issues that deserve further attention from historians. Paul Kennedy had a shot at addressing them in his Engineers of Victory (2013), but this was not among his more impressive books. It is welcome that James Holland, in this first installment of an intended multivolume narrative of the conflict, declares a commitment to explore the tactical and technological minutiae of the battlefields, as well as to provide extensive testimonies about the human experience, and he makes a fair start in The Rise of Germany, 1939–1941.

The most heartening aspect of serious modern World War II studies is that they have become less nationalistic. My British father and his contemporaries grew up believing that Churchill’s people had won the war, with the US supplying spam and chewing gum, while the Russians struggled in the eastern mists, doing heaven knew what.

Americans embraced their own comparable delusions, ignoring—for instance—how relatively small were the numbers of US troops fighting the enemy until mid-1944. Stephen Ambrose’s Band of Brothers (2001) was about Easy Company of the 101st Airborne Division, who proved outstanding soldiers when they finally got into combat. But their initiation, like that of much of the British army, came after two years of training and preparation, an unimaginable luxury for any Russian or German.

I was somewhat abused on both sides of the Atlantic back in 1984 when I asserted in my book Overlord that many, though not all, German wartime fighting formations were superior to their British or American counterparts. Today such a view is accepted by most serious historians, who also acknowledge the dominant role of the Red Army in destroying Hitler’s legions. David Stahel is an academic from New Zealand whose latest work on the 1941 Battle of Moscow continues his series of sound, solid narratives of the Eastern Front campaigns.

The struggle began in October, when the Germans launched Operation Typhoon, designed to seize Stalin’s capital before winter. By early December, it was plain—not least to Hitler’s generals—that they had failed to achieve a pivotal strategic objective. Though the Russians had suffered more than four million casualties since June, against 750,000 German losses, the Red Army could afford the blood, and the Wehrmacht could not.

As Stahel describes, during the three months of fighting west of Moscow it became plain that Hitler had catastrophically underrated Russian powers of resistance, and overrated the German economy’s ability to sustain a protracted campaign amid the vastness of the Soviet Union. The Russians transferred successive flood tides of reinforcements from the east to replace their dead, showing skill in deploying reserves, heroic stubbornness in defense, and energy in counterattack. By Christmas one in four of the Germans present at the launch of Operation Barbarossa in June 1941 had been wounded or killed, and far worse was to come. Stahel’s account is clear and comprehensive, though much of it is also familiar.

What else is new? After decades of ignorance or indifference, the British people are belatedly coming to terms with the famine in Bengal in 1943 and 1944 as one of the most shameful blots on our nation’s part in the war. At least a million Indians died, through culpable neglect. The British could have donated food to save many but did not do so. Yasmin Khan’s recent study India at War provides considerable detail about this ghastly story, but there is still plenty more useful work to be done about the internal governance of the British Empire while it fought its crusade in the name of freedom and democracy. The story in general is not wholly discreditable, but much less admirable than my generation was reared to suppose.

The Allied strategic bombing campaigns against Germany and Japan have undergone deep reevaluations, which seem likely to continue indefinitely, because both their moral shortcomings and economic achievements remain fiercely disputed. Much of the modern history written and read in Germany seeks to view the nation more as a victim of Hitler than his instrument. Some British and American works brand the bombing of German cities explicitly as a war crime.

The best recent effort, Richard Overy’s The Bombing War (2013), offers a comprehensive study of the contributions to victory of strategic air power—attacks on the enemy home front independent of ground force campaigns—as distinct from tactical air power—attacks on enemy troops, communications, oil stores, merchant shipping, and other targets in support of battlefield operations. It concludes that the strategic contribution was relatively small, certainly in relation to the industrial resources committed to it by the Allies. Overy also castigates the moral failings of air assault on civilians. (It would have been gracious for him to acknowledge that throughout his own earlier career as a historian, he was among the foremost public apologists for the RAF, and explicitly for its heavy bombers.)

New books continue to appear, recycling the operational story of the Allied aircrews, who suffered heavy losses, and celebrating their aircraft such as the B-17 Flying Fortress and RAF Lancaster, which inspire emotional admiration among techno-enthusiasts. There will assuredly be further polemics by those eager either to defend the wartime air forces from moral criticism or to denounce their campaigns and strategies. I for one, however, have read as much as seems rewarding about strategic bombing.

By contrast, there may be more to learn about the impact of air attack on the Axis economies. Professor Michael Howard observes regretfully that one of the weaknesses of his generation of historians—he was born in 1922—was an ignorance of economics. Recent studies of the 1939–1945 conflict are progressively remedying this gap in war studies, through such outstanding works as Adam Tooze’s The Wages of Destruction (2006), an exploration of the German war economy that examines how rearmament drove the German economic recovery under the Nazis. Here is another field in which revelations, of analysis rather than data discovery, continue to emerge, significantly modifying our view of the period. For example, Tooze argues that the idea of extermination through labor was a compromise between members of the SS who wanted to kill all the Jews and political leaders like Reinhard Heydrich, who wanted to use them for work.

For the most part, however, it seems fair to suggest that new books are written about World War II not because there is much new to be said that is useful to scholars, but because the public appetite for reading them appears inexhaustible.

-

1

Belknap Press/Harvard University Press, 2015; reviewed in these pages by Robert O. Paxton, February 25, 2016. ↩

-

2

Tim Duggan Books, 2015; see Christopher R. Browning’s review in these pages, October 8, 2015. ↩