More than halfway through his five-year term as president of China and general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party—expected to be the first of at least two—Xi Jinping’s widening crackdown on civil society and promotion of a cult of personality have disappointed many observers, both Chinese and foreign, who saw him as destined by family heritage and life experience to be a liberal reformer. Many thought Xi must have come to understand the dangers of Party dictatorship from the experiences of his family under Mao’s rule. His father, Xi Zhongxun (1913–2002), was almost executed in an inner-Party conflict in 1935, was purged in another struggle in 1962, was “dragged out” and tortured during the Cultural Revolution, and was eased into retirement after another Party confrontation in 1987. During the Cultural Revolution, one of Xi Jinping’s half-sisters was tormented to the point that she committed suicide. Jinping himself, as the offspring of a “capitalist roader,” was “sent down to the countryside” to labor alongside the peasants. The hardships were so daunting that he reportedly tried to escape, but was caught and sent back.

No wonder, then, that both father and son showed a commitment to reformist causes throughout their careers. Under Deng Xiaoping, the elder Xi pioneered the open-door reforms in the southern province of Guangdong and played an important part in founding the Special Economic Zone of Shenzhen. In 1987 he stood alone among Politburo members in refusing to vote for the purge of the liberal Party leader Hu Yaobang. The younger Xi made his career as an unpretentious, pragmatic, pro-growth manager at first in the countryside and later in Fujian, Zhejiang, and Shanghai, three of China’s provincial units that were most open to the outside world. In the final leg of his climb to power he was chosen in preference to a rival leader, Bo Xilai, who had promoted Cultural Revolution–style policies in the megacity of Chongqing.

For all these reasons, once Xi acceded to top office he was widely expected to pursue political liberalization and market reform. Instead he has reinstated many of the most dangerous features of Mao’s rule: personal dictatorship, enforced ideological conformity, and arbitrary persecution.

The key to this paradox is Xi’s seemingly incongruous veneration of Mao. Xi’s view of Mao emerges in the official biography of his father compiled by Party scholars, whose first volume was published when Xi was close to achieving supreme power and whose second came out after he had become Party general secretary and state president. Describing the elder Xi’s near execution in 1935, the book says that Mao saved his life, ordering his release with the remark that heads are not like scallions: if you cut them off they will not grow back. Mao then promoted Xi’s career as an official in Yan’an and as a top bureaucrat in Beijing after 1949.

With respect to Xi’s purge in 1962, the biography blames Mao’s secret police chief, Kang Sheng, rather than Mao himself, and claims that Mao protected Xi by sending him to a job in a provincial factory safely away from the political storms in Beijing. When the Cultural Revolution broke out a few years later and Red Guards “dragged out” Xi from this factory job to subject him to the physical abuse and denunciation called “struggle,” the biography says that Mao’s premier Zhou Enlai had Xi imprisoned in a military barracks near Beijing as a way of protecting him. These stories have doubtless been massaged to show Mao as Xi wants him to be shown. But they are grounded in historical reality and help to explain the complexity of Xi’s relationship to Mao’s legacy. As Xi said years later, “If Mao had not saved my father’s life, I would not be here today.”

Xi’s respect for Mao is not a personal eccentricity. It is shared by many of the hereditary Communist aristocrats who, as Agnès Andrésy points out in her book on Xi, form most of China’s top leadership today as well as a large section of its business elite. Deng Xiaoping in 1981 declared that Mao’s contributions outweighed his errors by (in a Chinese cliché) “a ratio of 7 to 3.” But in practice Deng abandoned just about everything Mao stood for. Contrary to the Western consensus that Deng saved the system after Mao nearly wrecked it, Xi and many other red aristocrats feel that it was Deng who came close to destroying Mao’s legacy.

Their reverence for Mao is different from the simple nostalgia of former Red Guards and sent-down youth who hazily remember a period of adolescent idealism. Rather, as the pro-democracy thinker Li Weidong writes in a much-discussed online essay, “The ‘Road of Red Empire’ That Cannot Be Traversed,” the children of the founding elite see themselves as the inheritors of an “all-under-heaven,” a vast world that their fathers conquered under Mao’s leadership. Their parents came from poor rural villages and rose to rule an empire. The second generation is privileged to live in a country that has “stood up” and is globally respected and feared. They do not propose to be the generation that “loses the empire.”

Advertisement

It is this logic that drives Liu Yuan, the son of former president Liu Shaoqi, whom Mao purged and sent to a miserable death, to support Xi in reviving Maoist ideas and symbolism; and the same logic has moved the offspring of many of Mao’s other prominent victims to form groups that celebrate Mao’s legacy, like the Beijing Association of the Sons and Daughters of Yan’an and the Beijing Association to Promote the Culture of the Founders of the Nation.1

The princelings seem to invest literal biological meaning in the “bloodline theory” of political purity that was popular among elite-offspring Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution: “If the father was a hero the son is a real man, if the father was a counterrevolutionary the son is a bad egg” (laozi yingxiong erzi haohan, laozi fandong erzi huaidan). They see no irony in cheering Xi Jinping’s attack on corrupt bureaucrats although Mao purged their own fathers as “capitalist roaders in power.” Mao’s purges they excuse as a mistake. But they see today’s bureaucrats as flocking to serve the Party because it is in power and not because they inherited a spirit of revolutionary sacrifice from their forebears. Such opportunists are worms eating away at the legacy of revolution.

The legacy is threatened by other forces as well. Xi holds office at a time when the regime has to confront a series of daunting challenges that have all reached critical stages at once. It must manage a slowing economy; mollify millions of laid-off workers; shift demand from export markets to domestic consumption; whip underperforming giant state-owned enterprises into shape; dispel a huge overhang of bad bank loans and nonperforming investments; ameliorate climate change and environmental devastation that are irritating the new middle class; and downsize and upgrade the military. Internationally, Chinese policymakers see themselves as forced to respond assertively to growing pressure from the United States, Japan, and various Southeast Asian regimes that are trying to resist China’s legitimate defense of its interests in such places as Taiwan, the Senkaku islands, and the South China Sea.

Any leader who confronts so many big problems needs a lot of power, and Mao provides a model of how such power can be wielded. Xi Jinping leads the Party, state, and military hierarchies by virtue of his chairmanship of each. But his two immediate predecessors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, exercised these roles within a system of collective leadership, in which each member of the Politburo Standing Committee took charge of a particular policy or institution and guided it without much interference from other senior officials.

This model does not produce leadership sufficiently decisive to satisfy Xi and his supporters. So Xi has sidelined the other members of the Politburo Standing Committee, except for the propaganda chief Liu Yunshan and the anticorruption watchdog Wang Qishan. He has taken the chairmanship of the most important seven of the twenty-two “leading small groups” that guide policy in specific areas. These include the newly established Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reform, which has removed management of the economy from Premier Li Keqiang. And Xi has created a National Security Council to coordinate internal security affairs.

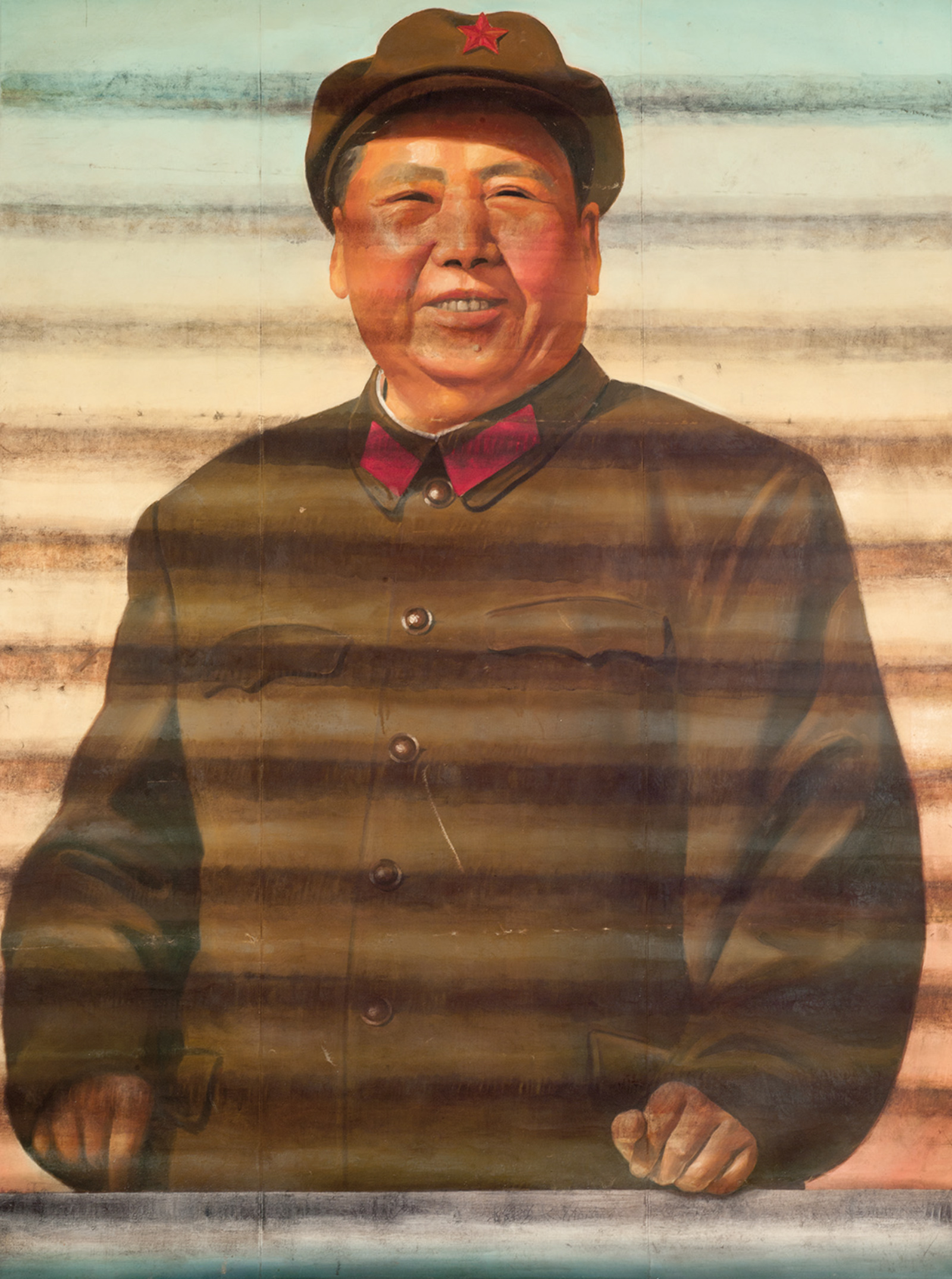

Ai Weiwei/Private Collection/Ai Weiwei Studio

Ai Weiwei: Mao (Facing Forward), 1986; from the exhibition ‘Andy Warhol/Ai Weiwei,’ which originated at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, and will be at the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, June 4–August 28, 2016. The catalog is edited by Max Delany and Eric Shiner and published by Yale University Press.

Xi emulates Mao in exercising power through a tight circle of aides whom he can trust because they have demonstrated their personal loyalty in earlier phases of his career, such as Li Zhanshu, director of the all-powerful General Office of the CCP Central Committee. As the scholar Cheng Li reported in China Leadership Monitor, Li Zhanshu published an article in September 2014, stating that work as an aide in formulating policy requires “absolute loyalty” and that staff in the General Office “should act and think in a manner highly consistent…with the order from the Central Committee led by General Secretary Xi Jinping.”2 Xi’s protégés occupy crucial positions in the bureaucracies responsible for security, for supervising official careers, and for propaganda. Unlike powerful staff members in recent previous administrations, his aides avoid contact with foreigners and even with officials outside Xi’s personal circle.

Advertisement

Xi has also followed Mao’s model in protecting his rule against a coup. His anticorruption campaign has made him numerous enemies, and there have been rumors of assassination attempts. However, as pointed out by James Mulvenon and Cheng Li, respectively, Xi has tightened direct control over the military by means of what is called a “[Central Military Commission] Chairman Responsibility System,” and he controls the central guard corps—which monitors the security of all the other leaders—through his longtime chief bodyguard, Wang Shaojun.3 In these ways Xi controls the physical environment of the other leaders, just as Mao did through his loyal follower Wang Dongxing.

Xi conveys Napoleonic self-confidence in the importance of his mission and its inevitable success. In person he is said to be affable and relaxed. But his carefully curated public persona follows Mao in displaying a stolid presence and immobile features that seem to convey either stoicism or implacability, depending on whether he is sitting through a boring speech or giving one. The propaganda agencies labor to generate a huggable image of “Daddy Xi,” and Xi appears to be genuinely popular among the public, although this is changing as the economy slows.4 But his anticorruption campaign affecting a great many people has ground on, leading intellectual and official elites to read his expression as inscrutable and frightening.

Above all, Xi has followed Mao in the demand for ideological conformity. He has invoked Mao’s “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art” in explaining why cultural and media workers must display “Party character” and serve as the Party’s “throat and tongue,” and has used the resolution that Mao wrote for the Party’s 1929 Gutian Conference to emphasize the importance of Party control of the army. He has warned Party members against “irresponsible talk” (wangyi) and academics against “universal values.” As David Shambaugh reports in his recent book China’s Future:

There has been an unremitting crackdown on all forms of dissent and social activists; the Internet and social media have been subjected to much tighter controls; Christian crosses and churches are being demolished; Uighurs and Tibetans have been subject to ever-greater persecution; hundreds of rights lawyers have been detained and put on trial; public gatherings are restricted; a wide range of publications are censored; foreign textbooks have been officially banned from university classrooms; intellectuals are under tight scrutiny; foreign and domestic NGOs have been subjected to unprecedented governmental regulatory pressures and many have been forced to leave China; attacks on “foreign hostile forces” occur with regularity; and the “stability maintenance” security apparatchiks have blanketed the country…. China is today more repressive than at any time since the post-Tiananmen 1989–1992 period.

But Xi is different from Mao in important ways. He has more accurate information than Mao did, thanks to extensive, organized, and professional systems of intelligence and analysis, and thanks to what he has gathered during his travel at home and abroad. He uses inner-Party star chambers and charges of corruption rather than screaming Red Guards and accusations of revisionism to purge rivals, and the political police rather than a mass movement to repress dissidents. Mao was a thinker and literary stylist; Xi has banal ideas but is more deliberate and consistent in decision-making. His personal habits appear to be orderly, compared to Mao’s chaotic ways of spending time. After a brief, failed first marriage Xi settled down with Peng Liyuan, a well-known singer who made her career in the military. Their relationship appears to be boringly conventional; even in rumor-drenched Beijing nothing has surfaced to suggest that he is a sexual hedonist like Mao. (Nor has the rumor mill produced allegations that Xi is personally corrupt, although Bloomberg News found that his older sister and her husband have made a lot of money.5)

And Xi is no revolutionary. He seeks neither to upend China nor to turn the clock back to rural communes and the planned economy. Rather, he has declared, it is forbidden to negate either of the “two thirty years”—that is, Mao’s era and then the post-Mao reform period. China must combine Maoist firmness with modernizing reform.

The reform he has in mind, however, is different from what many observers, both Chinese and Western, would like. After his rise to power, the first policy manifesto issued by his regime stated that “markets should play the decisive role in the allocation of resources,” but it has become clear that market forces are intended as a tool to invigorate, rather than to kill off, the “national champion” state-owned enterprises and state financial institutions that continue to enjoy state patronage and to make up a large part of the economy. Xi understands these as pillars of state power and would never hand control of the economy to enterprises that the Party does not control.

Xi wants “rule by law,” but this means using the courts more energetically to carry out political repression and change the bureaucracy’s style of work. He wants to reform the universities, not in order to create Western-style academic freedom but to bring academics and students to heel (including those studying abroad). He has launched a thorough reorganization of the military, which is intended partly to make it more effective in battle, but also to reaffirm its loyalty to the Party and to him personally. The overarching purpose of reform is to keep the Chinese Communist Party in power.

Xi’s stated goal is for China to achieve “a moderately prosperous society” (xiaokang shehui) by the hundredth anniversary of the Party’s founding in 2021, and “a socialist modernized society” (shehuizhuyi xiandaihua shehui) by the hundredth anniversary of the founding of the PRC in 2049.

These aims may sound modest, but they are bold. The goal for 2049 is said to imply a per capita GDP of US$30,000, and Chinese planners estimate that if it is achieved China will produce over 30 percent of the world’s GDP in that year, about one and a half times more than the proportion currently produced by the United States. That would generate a great deal of global power. However, 2049 is still a long way off. For now, Xi will not hesitate to strike back if he believes the country’s “core interests” around its periphery are at stake, but his priorities are fundamentally domestic.

Xi has made himself in some ways more powerful than Deng or even Mao. Deng had the final word on difficult policy issues, but he strove to avoid involvement in day-to-day policy, and when forced to make big decisions he first sought consensus among a small group of senior leaders. Mao was able to take any decision he wanted regardless of the will of his senior colleagues, but he paid attention to only a few issues at a time. Xi appears to be running the whole span of important policies on a daily basis, without needing to consult senior colleagues or retired elders.

He may go even further. There are hints that he will seek to break the recently established norm of two five-year terms in office and serve one or even more extra terms. He has had himself designated as the “core” of the leadership, a status that his immediate predecessor, Hu Jintao, did not take for himself. At this point in a leader’s first term we would expect to see one or two younger politicians emerging as potential heirs apparent, to be anointed at next year’s nineteenth Party Congress, but such signs are absent. One of the rumors circulating in Beijing is that teams of editors are compiling a book of Xi’s “thought” (sixiang), which would place him on a level with Mao as a contributor to Sino-Marxist theory, a status not claimed by any of Mao’s other successors to date.

Xi’s concentration of power poses great dangers for China. No one put it better than Deng Xiaoping, in a speech, “On the Reform of the System of Party and State Leadership,” delivered on August 18, 1980:

Over-concentration of power is liable to give rise to arbitrary rule by individuals at the expense of collective leadership, and it is an important cause of bureaucracy under the present circumstances…. There is a limit to anyone’s knowledge, experience and energy. If a person holds too many posts at the same time, he will find it difficult to come to grips with the problems in his work and, more important, he will block the way for other more suitable comrades to take up leading posts.

It was to avoid these problems that Deng built a system of tacit norms by which senior leaders were limited to two terms in office, members of the Politburo Standing Committee divided leadership roles among themselves, and the senior leader made decisions in consultation with other leaders and retired elders.

By overturning Deng’s system, Xi is hanging the survival of the regime on his ability to bear an enormous workload and not make big mistakes. He seems to be scaring the mass media and officials outside his immediate circle from telling him the truth. He is trying to bottle up a growing diversity of social and intellectual forces that are bound to grow stronger. He may be breaking down, rather than building up, the consensus about China’s path of development among economic and intellectual elites and within the political leadership. By directing corruption prosecutions at a retired Politburo Standing Committee member, Zhou Yongkang, and retainers of other retired senior officials, he has broken the rule that retired leaders are safe once they leave office, throwing into question whether it can ever be safe for him to leave office. As he departs from Deng’s path, he risks undermining the adaptability and resilience that Deng’s reforms painstakingly created for the post-Mao regime.

As the members of the red aristocracy around Xi circle their wagons to protect the regime, some citizens retreat into religious observance or private consumption, others send their money and children abroad, and a sense of impending crisis pervades society. No wonder Xi’s regime behaves as if it faces an existential threat. Given the power and resources that he commands, it would be reckless to predict that his attempt to consolidate authoritarian rule will fail. But the attempt risks creating the very political crisis that it seeks to prevent.

-

1

See, for example, news.sina.com.cn/c/2016-02-23/doc-ifxprqea5122519.shtml, history.sohu.com/20130830/n385376788.shtml, and news.163.com/13/1121/11/9E6V2N5E0001124J_all.html, accessed on March 10, 2016. ↩

-

2

Cheng Li, “Xi Jinping’s Inner Circle (Part 4: The Mishu Cluster I),” China Leadership Monitor, No. 46 (Winter 2015). ↩

-

3

James Mulvenon, “The Yuan Stops Here: Xi Jinping and the ‘CMC Chairman Responsibility System,’” and Cheng Li, “Xi Jinping’s Inner Circle (Part 5: The Mishu Cluster II),” China Leadership Monitor, No. 47 (Summer 2015). ↩

-

4

The term Xi Dada uses the character for “big” as in “Big-big Xi.” In various dialects it means father, grandfather, or uncle Xi. ↩

-

5

See “Xi Jinping Millionaire Relations Reveal Fortunes of Elite,” Bloomberg News, June 29, 2012. ↩