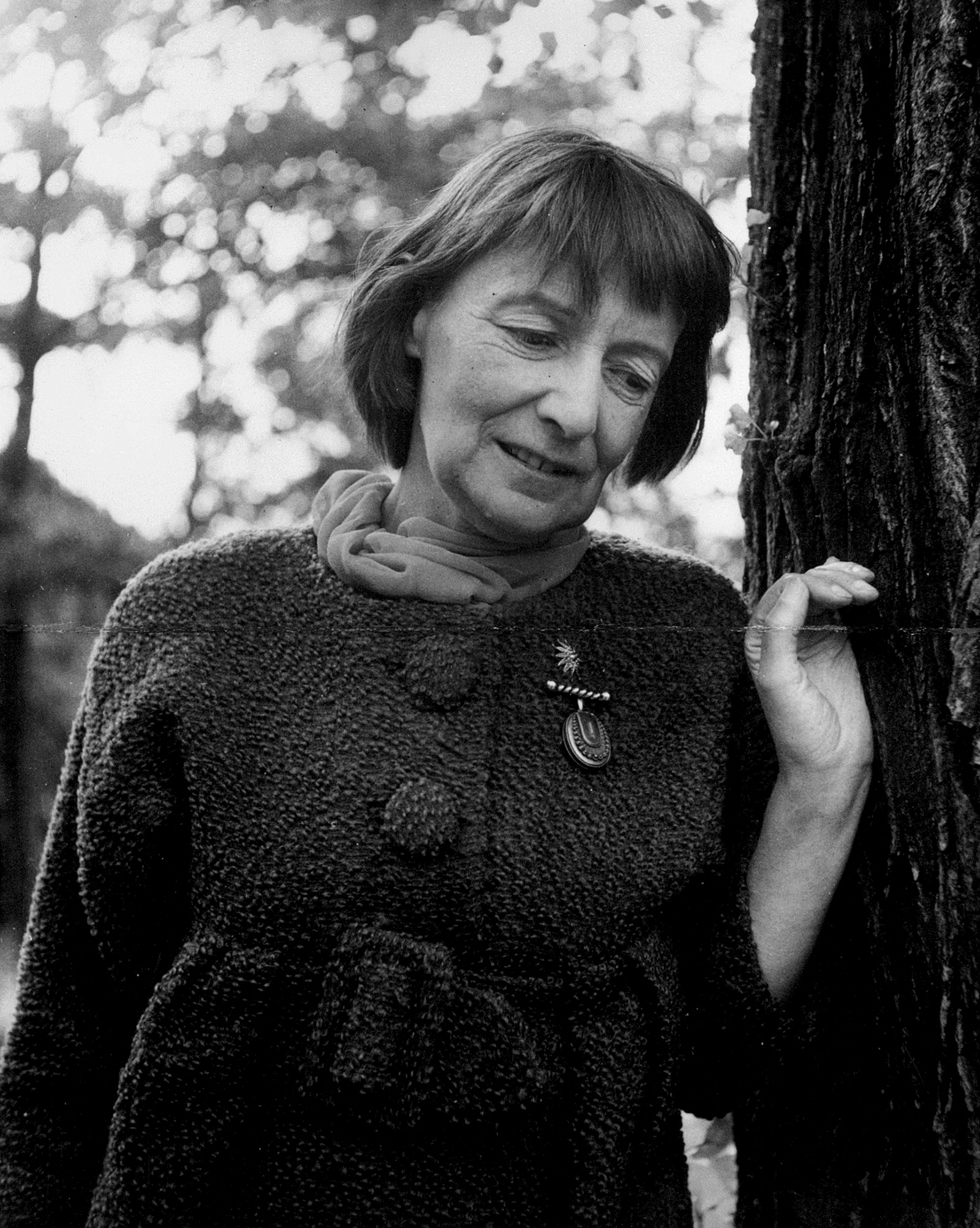

More than with most poets, when people write and talk about Stevie Smith (1902–1971), they try to nail her down with comparisons. She is a female William Blake, an Emily Dickinson of the English suburbs, a mixture of Dorothy Parker, Ogden Nash, and the Brothers Grimm. Her reading style, which became legendary, with her cropped hair, baleful expression, little-girl dresses, and singsong lugubrious chanting voice, was described (by Jonathan Miller) as a cross between Mary Poppins and Lawrence Olivier’s Richard III. Seamus Heaney called it a combination of Gretel and the witch. He also compared her to “two Lears,” “the old King come to knowledge and gentleness through suffering, and the old comic poet Edward veering off into nonsense.”1

She is often described as dotty, batty, silly, odd, childish, droll, or “fausse-naïve” (Philip Larkin’s term).2 Her English quirkiness and eccentricity are played up, as in Stevie, the play of 1977 by Hugh Whitemore (made into a film by Robert Enders in 1978), with Glenda Jackson as Stevie. Some readers throw up their hands in bafflement, as she told them they would, at the start of her 1936 Novel on Yellow Paper: “This is a foot-off-the-ground novel…and if you are a foot-on-the-ground person, this book will be for you a desert of weariness and exasperation.”3

Other readers are indulgent and curious, but reluctant to think of her as a professional poet, more as an amateur folk artist, a hit-or-miss ingenue (or enfant terrible). Fellow poets who have taken her seriously do so for different reasons. Heaney hears the accents of “a disenchanted gentility.” Amy Clampitt sees in her “the desolation of the ordinary.” D.J. Enright says she is “somewhat Greek”: austere, severe, and “bracing.”4 In the introduction to his edition of All the Poems, an invaluable and complete collection of her poems and drawings, Will May adds to the adjectival pursuit. He calls her trenchant, dogmatic, indignant, plaintive, stoic, eerie, shrewd, self-conscious, tricky, and uncompromising.

All these adjectives point to a poet who is hard to categorize and not really like anyone else at all. They also, often, suggest a writer who has been marginalized as an oddity. Now, forty-five years after her death, bound inside this large annotated collection, she can be celebrated as a major English poet of the twentieth century. She is a writer of astonishing skill, range, comedy, and depth of feeling; she is inimitable, strange, and utterly original. With her poetry collected as a whole, it becomes more apparent too that though she is a funny writer—funny-ha-ha and funny-peculiar—her work is melancholy and despairing, full of pain, terror, and grief: “Not waving but drowning.”

As Will May makes clear both in this edition and in the book he published six years ago, Stevie Smith and Authorship,5 it has not been an untroubled path from the appearance of her first novel and her first skinny, quirky-looking book of poems in 1937, to this solid production, which at last gives her the look of a classic. Until now, Stevie Smith’s poetry has been as evasive of mainstream and academic acceptance as her life has been resistant to biographers. Tellingly, her title for her first novel was “Pompey Casmilus,” after both the ruthless Roman general and the wily, untamed messenger of the gods, alias Hermes or Mercury.

The bare facts of the life, as summed up by Will May, don’t look enticing:

Stevie Smith was born in Hull in 1902, moved to Palmers Green [a North London suburb] aged three, and lived there for the rest of her life. After school, she spent thirty years working at Newnes Publishing as a secretary to Sir Neville Pearson, and produced three semi-autobiographical novels and eight collections of poetry.

Some color can be added to this, drawing on Frances Spalding’s sympathetic biography. There was her upbringing in what Stevie Smith calls “a house of female habitation” (mother, sister, aunt) after her father, an unsuccessful shipping agent in Hull, ran away to sea soon after she was born, leaving behind “a cynical babe.” There was the death of her mother when she was seventeen, and the consoling presence of her Aunt Madge—“Auntie Lion”—who moved the whole family south, and looked after Stevie Smith until it was her turn to be looked after.

There was her dislike of her disciplinarian school, North London Collegiate, where, however, she had a useful classical education and started to write. There was her adoption of her androgynous writing name, taken from a popular jockey called Stevie Donoghue. (Her given name was Florence.) There was her opting for a dull secretarial job so that she had time to write (on yellow office paper). There was her move away from Christianity to a troubled skepticism. There were a few unsatisfactory love affairs with both men and women, and an interesting range of literary friendships (many of them wrecked by her tendency to put them into her fiction) including with George Orwell, Inez Holden, Betty Miller, Kay Dick, Mulk Raj Anand, Olivia Manning, Naomi Mitchison, Rose Macaulay, and Veronica Wedgwood.

Advertisement

As Will May says, although in interviews she liked to play “the unconnected and isolated figure,” she had a rapid, eye-catching career as a poet and novelist from the mid-1930s to the late 1940s. Novel on Yellow Paper aroused much fascination. One poet-reader was convinced that the book, with its free-associating, meandering, quizzical voice, was by Virginia Woolf, and wrote to tell her so: “You are Stevie Smith. No doubt of it. And Yellow Paper is far and away your best book.”6 Certainly it became a cultish hit, and after that, books poured out of her: the poetry collections with their quizzical titles—A Good Time Was Had by All (1937), Tender Only to One (1938), Mother, What Is Man? (1942), Harold’s Leap (1950)—and the novels, full of angry arguments about religion, war, politics, and marriage—Over the Frontier (1938) and The Holiday (1949).

In the 1950s, there was a slump into relative obscurity, neglect, and depression. One of the less-well-known poems in the new edition, called “They Killed,” is savage on the subject of literary neglect and condescension:

They killed a poet by neglect

And treating him worse than an insect

They said what he wrote was feeble

And should never be read by serious people

Serious people, serious people,

I should think it was serious to be such people.

Her haunting radio play of the 1950s, A Turn Outside, dramatized a poet very like herself reading and singing her work while haunted by the ever-closer figure of death. She had a crisis at the office in July 1953, an attack on her genial employer that turned into a suicide attempt (with a pair of scissors) and led to her being fired.

But in the 1960s, with the rise of performance poetry and a new interest in women writers, she had a return to popularity, as a reciter of her own work and as a reviewer and a broadcaster. There was some remarkable late work, such as the poetry collections The Frog Prince (1966) and Scorpion and Other Poems (1972). She made her own selection of her poems and drawings, published in England and America as Selected Poems in 1962. In the last ten years of her life, she became well known and well loved, and in 1969 she was awarded the Queen’s Gold Medal for poetry. According to Stevie Smith’s version of this encounter, the queen remarked that she had been told that Smith lived in a house with nine rooms all on her own. Smith “thought this remark odd, considering how many rooms the Queen lived in, but replied that it was better for one person to live in nine rooms quite happily than for nine people to live in nine rooms and not get on.”

Scorpion and Other Poems was published after her death, from a brain tumor, in March 1971. From then on, her posthumous publishing life was not straightforward. She was in the habit of slightly altering her poems in her readings and recordings. Her drawings—part cartoons, part doodles, part character sketches of children or people or animals, with (Will May notes) a touch of George Grosz and more than a touch of Edward Lear—were free-floating elaborations of the writing. As she said in a radio interview in 1963:

This delightful moment comes, which is the moment that I like best, in fact the only moment I really like, when a book of poems is going to be published and you choose the right drawing for the poem and you have all these drawings on the floor, on the table, and you think well that one will do and that one and then when you’re looking one of the drawings will often inspire another poem, then you write another poem.7

Her executor, the publisher James MacGibbon, did his best to keep her work in print but made some inconsistent decisions. His Collected Poems in 1975 varied in its choice of texts and omitted uncollected poems. In 1978, his Selected Poems (a different choice from her own 1962 selection) left out many of the drawings. MacGibbon took issue with two American academic devotees, Jack Barbera and William McBrien, who published, with Virago, an interesting new selection of poems, stories, essays, reviews, and letters called Me Again, in 1981.

In 1985 they did a biography, with Heinemann, not welcomed by MacGibbon, who then commissioned Frances Spalding to write another life, published in 1988 by Faber and never superseded. Meanwhile MacGibbon allowed Virago to reissue the three novels (Carmen Callil, Virago’s founder-editor, was a great enthusiast of Stevie Smith) and gave me permission to do a small Faber selection, annotated for student readers, in 1983, one of several selections and anthologizings of her work, with her most anthologized poem being “Not Waving But Drowning.” This scattered publication history, across four publishing houses—Longmans, Faber, Heinemann, and Virago—has made for a long journey to this complete edition. Now we need well-edited new publications of all the novels and stories, the essays, and the letters.

Advertisement

Will May opts for Stevie Smith’s final versions, notes earlier variants, provides brief but helpful notes to her wide and eclectic variety of sources and allusions, and gives clues to some of the characters in the poems. Though consistency must be the best editorial policy, occasionally I regret his commitment to her final choices. Here’s a small example involving apostrophes. In one of her wry retellings of fairy stories, “The After-thought,” Rapunzel’s lover, a garrulous fellow, is waiting at the bottom of her tower till she lets down her long golden hair so he can climb up to meet her. This time, he says, he will bring a rope ladder with him so they can escape, such a blindingly simple afterthought that “just because it is perfectly obvious one is certain to overlook.” He rambles on about Edgar Allan Poe, centipedes, Indian gurus, and the tendency of the human mind toward introspection, and then breaks off, as if he is talking on a bad phone line to someone who hasn’t gotten a word in edgewise. (Paraphrase can’t bring home the endearing absurdity of this dramatic monologue.) He ends:

What is that darling? You cannot hear me?

That’s odd. I can hear you quite distinctly.

Will May’s version has apostrophes (“What’s that, darling? You can’t hear me?”), less funny because less formal and pompous.

“You cannot hear me?/That’s odd.” Stevie Smith’s poems are full of unanswered or unanswerable questions, conversations that go awry, misunderstandings, cross-purposes, and the drawing of blanks. This evasiveness or intractability is particularly on show when she is writing about publishers, literary editors, critics and pundits, and unresponsive readers:

TO AN AMERICAN PUBLISHER

You say I must write another book? But I’ve just written this one.

You liked it so much that’s the reason? Read it again then.

Or elsewhere:

WHO IS THIS WHO HOWLS AND MUTTERS?

Who is this that howls and mutters?

It is the Muse, each word she utters

Is thrown against a shuttered door

And very soon she’ll speak no more….

In his book on Stevie Smith, Will May talks about her tricky, slippery relationship with her intermediaries and her readers. She could play “fausse-naïve” with her publishers, but she was shrewd and self-aware and knew exactly the kind of impact her work had. A letter to her American editor, James Laughlin, in 1963, struck a warning note:

I am not sure it is altogether a good thing to use the words whimsical and primitive as it is rather handing a gun to critics and anyway I dont [sic] really think they (tone and metre) are…. I should hate even a hint of being sold as a Funny Little Thing, Nash-manquee [sic].

Even when she is at her most perverse, she knows what she is up to. Here is a famous example of her mixture of weirdness and willfulness:

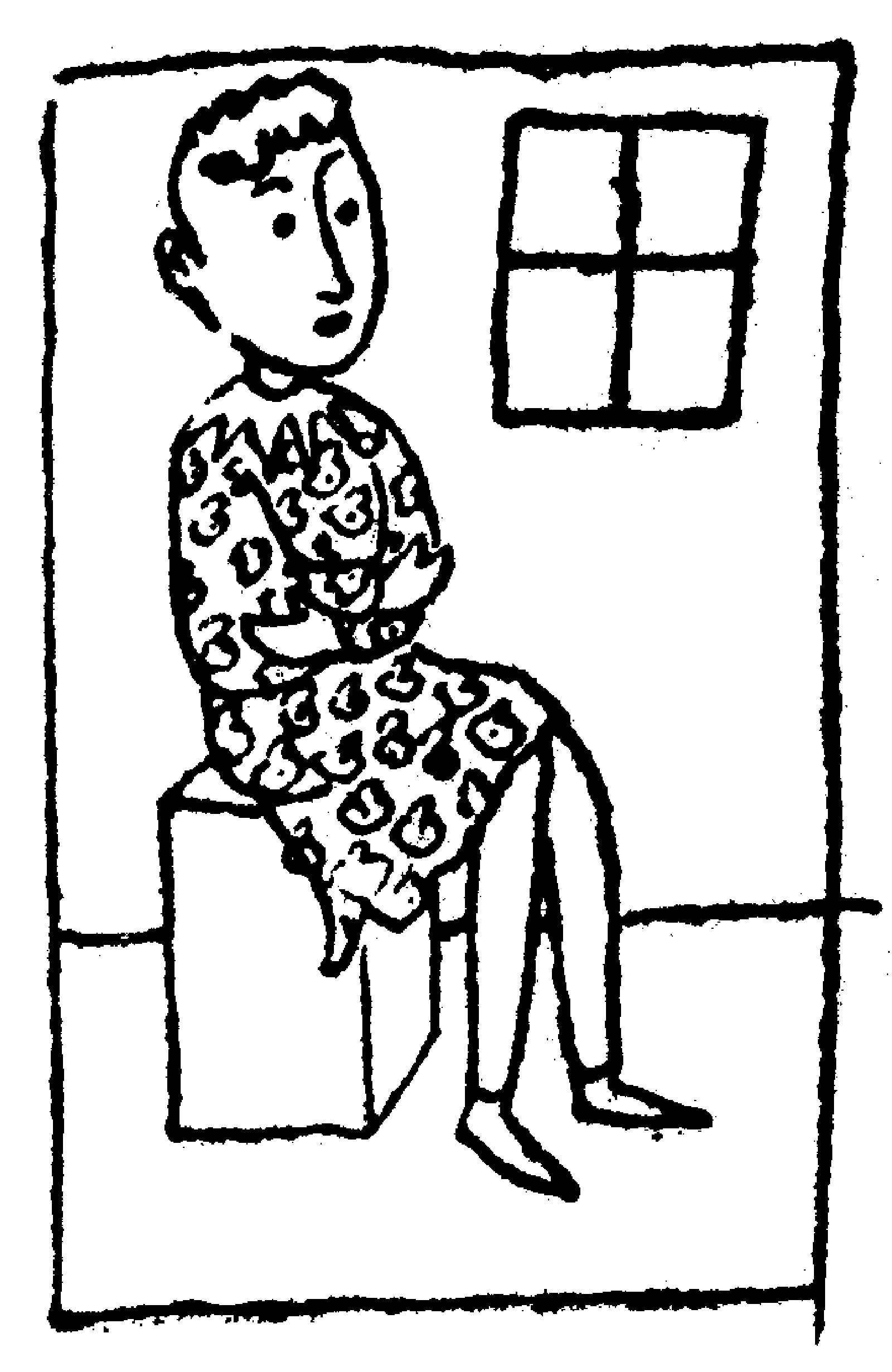

CROFT

Aloft,

In the loft,

Sits Croft;

He is soft.

This goes with a drawing of an androgynous figure with arms crossed, in a flowered dress, sitting on a chair, inside a frame, with a small window above. Her comments on this were: “They will probably write off the simple ones, as they wrote off poor Croft.” And: “He is soft… may be their point of view about it, but it is not ours.”8 Is Croft a prisoner? A lunatic? A recluse? An unrecognized poet? A transgender misfit? Or, as in the poem “To Carry the Child,” a “poor child…Trapped in a grown-up carapace,” who can only “peer outside of his prison room/With the eye of an anarchist”? “Work it out for yourself, reader,” as she says in Novel on Yellow Paper. Whatever Croft is, he is definitely asocialized, one of many Stevie Smith personae who cast a bewildered or bad-tempered glance on the world.

Dressing up as Croft, or as Rapunzel’s lover, is a typical ploy. Stevie Smith may have an idiosyncratic and memorable voice, but she also loves performances, masks, and adaptations. A slippery character, she both reveals and conceals herself in her disguises. She turns herself into animals, ghosts, angels, rivers, children, and mythological beings. She reworks nursery rhymes, hymns, biblical texts, fairy tales, and classical myths. She steals, echoes, parodies, and rewrites, wildly and freely, a rich array of (male) authors, from Catullus, Euripides, Dante, Shakespeare, and Racine to Tennyson, Browning, Blake, Shelley, and Baudelaire. This appropriation of others is part of what makes her not a quaint suburban English lady writer, but European, classical, and sophisticated. There is a huge stratum of world literature bedded down under her singular style.

Many of her rewritings involve refusals and a resistance to fate and the inevitable. If you are already a character in a well-known myth or a person in history, how can you have a life of your own? Helen of Troy wrestles with this conundrum in “I had a dream…,” wandering around the besieged Trojan palace for nine years, bored to tears with stupid Paris, trying to get a laugh out of Cassandra, and resentful of the part she is doomed to play: “It is an ominous eternal moment I am captive in.” The frog who is due to be turned into a prince when, after a hundred years, the maiden kisses him would really much rather stay as he is. But he knows it is “part of the spell” to be content with a quiet life, to “make much of being a frog.” He knows he will have to be disenchanted one day, as “only disenchanted people/Can be heavenly.” Persephone, abducted to the underworld by Pluto, wishes her mother would stop looking for her; she is much happier in the kingdom of darkness. King Arthur rides off into another world so he can lay down “his reigning power” and get away from Guinevere, who is left in the palace calling: “Arthur, where are you, dear?”

There is nothing feminist or even gendered about these rewritten legends: the mythic figures all just want to turn their backs on the story that has been told about them, or the life they are in. The same is true of many of her invented characters, like the girl who is lifted away to a desert island by her gigantic hat and hopes to stay there (“Go home, you see, well I wouldn’t run a risk like that”), or Joan, who walks in front of a Turner picture in the National Gallery all day and is at last sucked away into the painting to live forevermore on “the painted shore…/ In a happy happy light.” Dark woods, empty places, bright shorelines, imaginary landscapes empty of other people are what her solitaries desire.

One of her most famous, brilliant, and melancholy rewritings is “Thoughts about the Person from Porlock.” The story goes that Coleridge was writing “Kubla Khan,” which had come to him in a dream, but was interrupted by a person calling on business from the village of Porlock and was afterward unable to recall the dream and complete the poem. Stevie Smith’s version is that Coleridge was only too glad of the interruption:

As the truth is I think he was already stuck

With Kubla Khan.

He was weeping and wailing, I am finished, finished,

I shall never write another word of it

When along comes the Person from Porlock

And takes the blame for it.

She wonders comically about who the Person from Porlock was, and then turns him into the Person she too is waiting for:

I long for the Person from Porlock

To bring my thoughts to an end,

I am becoming impatient to see him

I think of him as a friend….

By the end of the poem the Person from Porlock has become death, or death’s messenger, Stevie Smith’s most longed-for visitor. Much more Greek or Roman than Christian in her attitude toward death, she agrees with Seneca that death must come when you call him. Harold was right to take his “leap.” Many of her personae, from Pompey in Novel on Yellow Paper to Scorpion at the end of one of her last great poems (“Scorpion so wishes to be gone”) call upon death to come to them. But she is also a Stoic and despises those who give up too easily. The “Person from Porlock” poem ends by recommending cheerfulness and work as a substitute for extinction:

Smile, smile and get some work to do

Then you will be practically unconscious without positively having to go.

Among the previously uncollected poems included in the new edition, there is a last and extraordinary example of her argument over “having to go”:

She got up and went away

Should she not have? Not have what?

Got up and gone away.

Yes, I think she should have

Because it was getting darker.

Getting what? Darker. Well,

There was still some

Day left when she went away, well,

Enough to see the way.

And it was the last time she would have been able…

Able?…to get up and go away.

It was the last time the very last time for

After that she could not

Have got up and gone away any more.

It is one of her uncomfortable conversations, in which the speaker and the interlocutor seem not to understand each other, or are barely able to hear each other (“Not have what?” “Getting what?”), sounding more like Beckett than anyone else she’s been compared with. It is built up out of the simplest possible language and the most ordinary expressions—“it was getting darker,” “enough to see the way,” “well,” “well,/Enough,” “the last time”—made ominous and fearful through insistence. Under the flat colloquial voice it has the vestige of poetic form, starting off with a four-stress bounce that looks as if it might turn into a hymn or ballad rhythm, and then fragmenting. It rhymes with itself, or not at all. With its fourteen lines it has the faintest trace of a sonnet.

But the speaking voice is breaking up, with its dots and halts and repetition, as it tries to say the unsayable. And what is that? That if you want to choose your death you have to kill yourself before you’re too old and feeble to do it? That the old and ill should be allowed to make a last bid for freedom, and not have to be looked after or kept under surveillance? Or perhaps nothing so polemical as this, but just a knowledge that getting up and going away is, in her view, always the preferable choice. “Well,/Enough…”

This Issue

June 9, 2016

In DeLillo’s Icy Future

‘Life’s Greatest Secret’

-

1

See Seamus Heaney, Finders Keepers: Selected Prose, 1971–2001 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002), p. 421. ↩

-

2

Philip Larkin, Required Writing (Faber, 1983), pp. 153–158. ↩

-

3

Novel on Yellow Paper (Jonathan Cape, 1936), p. 1. ↩

-

4

See Amy Clampitt, Predecessors, Et Cetera (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 1991), p. 123, and D.J. Enright, Man Is an Onion (Chatto and Windus, 1972), p. 137. ↩

-

5

Oxford University Press, 2010. ↩

-

6

See Frances Spalding, “Robert Nichols to Virginia Woolf,” in Stevie Smith: A Critical Biography (Faber, 1988), p. 115. ↩

-

7

See Will May, Stevie Smith and Authorship (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 103. ↩

-

8

See Me Again, edited by Jack Barbera and William McBrien (Virago, 1981), pp. 108, 115. ↩