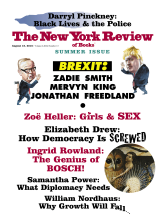

Rania Matar/Institute

Danielle, Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, 2010; photograph by Rania Matar from her book A Girl and Her Room (2012), which collects her portraits of teenage girls in their bedrooms in the US and Lebanon. It includes essays by Susan Minot and Anne Tucker and is published by Umbrage Editions.

By some measures, girls appear to be faring rather well in twenty-first-century America. Teenage pregnancy rates have been in steady decline since the 1990s. Girls have higher graduation rates than their male counterparts at all educational levels. The popular culture abounds with inspirational images and anthems of girls “leaning in” and “running the world.” But according to two new, rather bleak books, these official signs of progress have given us an unduly rosy impression of the modern girl’s lot.

In American Girls, a study based on interviews with more than two hundred girls, Vanity Fair writer Nancy Jo Sales argues that the most significant influence on young women’s lives is the coarse, sexist, and “hypersexualized” culture of social media. American girls may appear to be “among the most privileged and successful girls in the world,” she writes, but thanks to the many hours they spend each day in an online culture that treats them—and teaches them to treat themselves—as sexual objects, they are no more, and perhaps rather less, “empowered” in their personal lives than their mothers were thirty years ago.

All young female social media users, Sales contends, are assailed “on a daily, sometimes hourly, basis” by misogynist jokes, pornographic images, and demeaning comments that “are offensive and potentially damaging to their well-being and sense of self-esteem.” In addition to this steady stream of low-level sexual harassment, many girls are subject to more aggressive forms of sexual teasing and coercion: having their attractiveness crudely assessed on “hot or not” websites, receiving unsolicited “dick pics” on their phones, being pestered or blackmailed for nude photos. (A group of thirteen-year-olds in Florida explain to Sales that girls who acquiesce to demands for “nudes” run the risk of having their photos posted on amateur porn sites, or “slut pages,” while those who demur are usually punished in some other way—by being branded “prudes,” or by having sexual rumors spread about them.)

The unsparing gaze that social media train on girls’ sexuality—the supreme value that they place on being sexually appealing—engenders a widespread female anxiety about physical appearance that is highly conducive to “self-objectification,” Sales claims. All of her interview subjects agree that on sites like Instagram and Facebook, female popularity (as quantified by the number of “likes” a girl’s photos receive) depends on being deemed “hot.” “You have to have a perfect body and big butt,” a fifteen-year-old from the Bronx observes grimly. “For a girl, you have to be that certain way to get the boys’ attention.” Girls who spend long enough in this competitive beauty pageant atmosphere don’t need to be coerced into serving themselves up as masturbatory fantasies, Sales argues. Taking their cues from celebrities like Kim Kardashian—whose vast following on Instagram Sales identifies as a marker of social media’s decadent values—they post “tit pics,” “butt pics,” and a variety of other soft-porn selfies as a means of guaranteeing maximum male attention and approbation. “I guarantee you,” a seventeen-year-old from New Jersey tells Sales,

every girl wishes she could get three hundred likes on her pictures. Because that means you’re the girl everybody wants to fuck. And everybody wants to be the girl everybody wants to fuck. Every girl who isn’t that girl secretly hates herself…. It’s empowering to be hot…. Being hot gets you everything.

The “empowering” nature of hotness is a theme that crops up frequently in Sales’s book. A number of the girls she meets vehemently reject the notion that they are oppressed or objectified on social media. On the contrary, they tell her, they are proud to be sexy “hos” and their highly sexualized self-presentation is a freely chosen expression of their “body confidence.” Naturally, Sales is not much persuaded by these claims. The fact that being “the girl everybody wants to fuck” can now be characterized as a bold, feminist aspiration is one measure, she suggests, of how successfully old-fashioned sexual exploitation has been sold to today’s teenage girls as their own “sex-positive” choice.

Peggy Orenstein, the author of Girls and Sex, is equally skeptical about the emancipatory possibilities of hotness. “Whereas earlier generations of media-literate, feminist-identified women saw their objectification as something to protest,” she writes, “today’s often see it as a personal choice, something that can be taken on intentionally as an expression rather than an imposition of sexuality.” Her investigation into the sex lives of teenage girls finds plenty of evidence to suggest that the confidence and power conferred by “a commercialized, one-dimensional, infinitely replicated, and, frankly, unimaginative vision of sexiness” is largely illusory. This generation of girls, she argues, has been trained by a “porn-saturated, image-centered, commercialized” culture “to reduce their worth to their bodies and to see those bodies as a collection of parts that exist for others’ pleasure; to continuously monitor their appearance; to perform rather than to feel sensuality.” As a result, they are eager to be desired, but largely clueless about what their own desires might be, or how to satisfy them; they go to elaborate lengths to attract male sexual interest, but regard sex itself as a social ritual, a chore, a way of propitiating men, rather than as a source of pleasure.

Advertisement

Orenstein, it is worth noting, is not concerned about the quantity of sex that young women are having. (There is, she points out, no evidence to suggest that rates of sexual intercourse among young people have risen in recent decades.*) Her interest lies rather in the quality of young women’s sexual experiences. “The body as product…is not the same as the body as subject,” she observes sternly.

Nor is learning to be sexually desirable the same as exploring your own desire: your wants, your needs, your capacity for joy, for passion, for intimacy, for ecstasy…. The culture is littered with female body parts, with clothes and posturing that purportedly express sexual confidence. But who cares how “proud” you are of your body’s appearance if you don’t enjoy its responses?

Orenstein interviewed more than seventy young women for her book, each of them chosen to represent those who had “benefited most from women’s economic and political progress.” All were at college or college-bound, and almost all struck her as “bright, assertive, ambitious” students. Yet their sexual histories, she reports, were characterized less by joy, ecstasy, or even minimal satisfaction than by discomfort, intimidation, and a chronic lack of “self-efficacy.” Half of them had suffered “something along the spectrum of coercion to rape.” And much of what they described about even their consensual experiences was “painful to hear.” Although many of them led active sex lives and professed to find sex “awesome,” few had ever achieved orgasm with a partner. (Most of them had faked it.) And while the majority of them regarded providing oral sex as a mandatory feature of the most fleeting sexual encounter, they rarely received, or expected to receive, oral sex in return. (Several rejected the idea of cunnilingus as embarrassing and worried that their vaginas were “ugly, rank, unappealing.”)

Some of the misery of teenage girls’ sexual experiences is attributable, Orenstein contends, to the “hookup culture” in which sex, “rather than being a product of intimacy…has become its precursor, or sometimes its replacement.” (Rates of female orgasm are much lower for casual encounters, she notes, than for sex that takes place within committed relationships.) Another contributing factor, she suggests, is the part that pornography now plays in determining normative standards of teenage sexual behavior. As one example of this, she points to the fact that most of her interview subjects had been dutifully shaving or waxing their “bikini areas” since the age of fourteen. (Rather like Ruskin, whose ideas about the naked female form are said to have been gleaned from classical statuary, modern porn-reared boys expect female genitalia to be hairless.)

She also notes that, in the years since the Internet made hardcore porn widely accessible to teenage boys, anal sex has become a more or less standard feature of the heterosexual repertoire. (In 1992, only 16 percent of women aged eighteen to twenty-four had tried anal sex; today, the figure has risen to 40 percent.) Despite the fact that most girls report finding anal penetration unpleasant or actively painful, they often, Orenstein claims, feel compelled to be good sports and submit to it anyway. (According to one study she cites, girls are four times as likely as boys to consent to sex they don’t want.) Among the girls she interviewed, the most common reasons given for doing so were a fear of being considered “uptight” and a desire to avoid “awkwardness.”

History has taught us to be wary of middle-aged people complaining about the mores of the young. The parents of every era tend to be appalled by the sexual manners of their children (regardless of how hectic and disorderly their own sex lives once were, or still are). There were some in the 1950s who were pretty sure that the decadent new practice of “going steady” augured moral disaster. Both Sales and Orenstein have undoubtedly grim and arresting information to impart about the lives of American girls. And neither of them can be dismissed as a sexual puritan. (They are not troubled about teenagers leading active sex lives, they assure us, only about the severely limited forms in which female sexuality is currently allowed to express itself; they are not even against casual sex per se, just eager to ensure that there should be, as Orenstein puts it, “reciprocity, respect, and agency regardless of the context of a sexual encounter.”) Even so, neither of their books entirely avoids the exaggerations, the simplifications, the whiff of manufactured crisis that we have come to associate with this genre.

Advertisement

Both writers make rather invidious comparisons between the frenzied, romance-free social lives of today’s young women and their own halcyon youths. Sales recalls walking back from school with her ninth-grade boyfriend to do homework together at her house. “The point of being together was not to have sex, necessarily. It was to become intimate,” she writes. Orenstein observes that her college experience was not about binge-drinking and hook-ups, but “late-night talks with friends, exposure to alternative music and film, finding my passions, falling in love.”

To use these sun-dappled recollections of life before the iPhone as a way of pointing up the misery of girls’ present conditions is a little misleading. To be sure, certain kinds of sexism have been amplified—or perhaps transmitted more efficiently—in the Internet era, and girls are now under pressure to present themselves as pliable sexual creatures at a much earlier age than they have been in the past. But even in the far-off 1970s and 1980s, young women experienced their share of exploitation, abuse, and unsatisfactory sex. Witness the feminist writer Ellen Willis drily reporting on the state of the sexual revolution in 1973:

For men, the most obvious drawback of traditional morality was the sexual scarcity—actual and psychic—created by the enforced abstinence of women…. Sex was an illicit commodity, and whether or not a sexual transaction involved money, its price almost always included hypocrisy; the “respectable” man who consorted with prostitutes and collected pornography, the adolescent boy who seduced “nice girls” with phony declarations of love (or tried desperately to seduce them)….

Men have typically defined sexual liberation as freedom from these black-market conditions: the liberated woman is free to be available; the liberated man is free to reject false gentility and euphemistic romanticism and express his erotic fantasies frankly and openly…. Understandably, women are not thrilled with this conception of sexual freedom.

If the good old days were never as good as both writers are wont to imply, the dark days of our present era are not quite as unremittingly desperate either. Notwithstanding the vicious influence of pornography, social media, and Miley Cyrus, contemporary girls still manage to have high school boyfriends; some of them even get around to watching alternative films at college. Fifteen-year-olds may go online to learn how to perform fellatio, but they also post fearsome rebukes to boorish boys on Facebook and have lengthy debates on Twitter about whether or not Kim Kardashian is really a good “role model.” Girls use editing apps to whiten their teeth in their selfies and fret about the size of their “booties,” but they also celebrate the sororal power of “girl squads” and attend Nicki Minaj concerts to hear the rapper sermonize on why a woman should never be financially dependent on a man.

Sales portrays social media as an irresistible and ubiquitous force in the lives of young women. All of the girls in her book, regardless of their socioeconomic background or individual circumstances, are presented as being equally in thrall to their phones and computers. Some are queen bees, most are drones, but all are trapped in the social media hive. None of them appears to have a single cultural resource or pursuit outside of its ambit. (The one exception is a young woman who doesn’t own a smartphone—but that’s because she’s homeless and itinerant.) Is this an accurate representation of social media’s utter dominion, one wonders, or a reflection of Sales’s rather narrow line of questioning? (If you gathered up two hundred young women and asked them exclusively about their pets, you could probably write a shocking exposé of the outsized role that domestic animals play in the lives of American girls.)

Orenstein offers a rather more nuanced and measured account of the way girls live now, but she too has a tendency to underestimate the heterogeneity of teenage culture and the multiplicity of ways in which girls engage with it. At the start of her book she notes that the meanings of cultural phenomena are complex. Selfies are neither simply “empowering” nor simply “oppressive,” and wearing a short skirt is neither just “an assertion of sexuality” nor just “an exploitation of it.” Better, she suggests, to think of these issues in terms of “both/and.” Yet more often than not, she ignores this advice and opts for the reductive language of “might seem, but is actually.” Thus, Beyoncé may appear to be an inspiring, powerful figure, but she is actually “spinning commodified sexuality as a choice.” Girls may think they’re powerful when they look hot, but in fact, “‘hot’ refracts sexuality through a dehumanized prism regardless of who is ‘in control.’”

Orenstein is most convincing when she addresses the passivity, the “concern with pleasing, as opposed to pleasure,” that characterize her interview subjects’ approach to sex. Young women’s propensity to give male satisfaction priority over their own is not a new development, but Orenstein is surely right to be indignant about how little has changed in this regard over the last fifty years. Her belief that new, stricter definitions of consent on college campuses are a step toward establishing “healthy, consensual, mutual encounters between young people” is perhaps unduly optimistic. Setting aside the question of whether it is useful or fair to apply the bright line of “yes means yes” to sexual situations that tend, by her own admission, to be blurry and complicated, the new college codes assume a female confidence, a willingness to challenge the primacy of men’s sexual wishes, that many of Orenstein’s subjects have specifically demonstrated they lack. Making young men more vigilant about obtaining consent and discouraging their tendency “to see girls’ limits as a challenge to overcome” is no doubt essential, but if young women are still inclined to say “yes” when they mean “no”—are more willing to endure unwanted sex than to risk being considered prudish—the new standards of consent would seem to be of limited value.

Far more interesting and persuasive are Orenstein’s recommendations for revising the American approach to sex education. In place of the failed “abstinence-only” programs (that have used up $1.7 billion in government funding over the last thirty-five years) she proposes offering classes that frankly address all aspects of teenage sexuality, including female pleasure. (Even the most comprehensive sex education classes currently on offer in high schools fail to mention the existence of the clitoris, she notes.) In addition to candid discussions of “masturbation, oral sex, homosexuality, and orgasm,” this new sex education curriculum would offer guidance on how to make decisions and to “self-advocate” in sexual encounters.

The idea of encouraging girls to speak up for themselves—of promoting their ability to ask for what they want and to refuse what they don’t—seems an eminently sensible one. “Assertiveness training” for women has gone out of fashion in recent years. Indeed much of the recent discourse about girls and sex has tended to reinforce rather than to challenge the idea of female vulnerability and victimhood. It would be a salutary thing to have some old-school feminist pugnacity injected back into the culture.

-

*

The Online College Social Life Survey, conducted in 2010, found that 20 percent of college students “hook up”—that is, engage in some form of sexual activity with a partner—ten times or more by senior year; 40 percent hook up three times or fewer; and only a third of all hookups include intercourse. Another 2013 survey published earlier this year by the Centers for Disease Control found that the number of American high school students who reported having had sexual intercourse had actually decreased over the last decade from 47 percent to 41 percent. ↩