C-SPAN

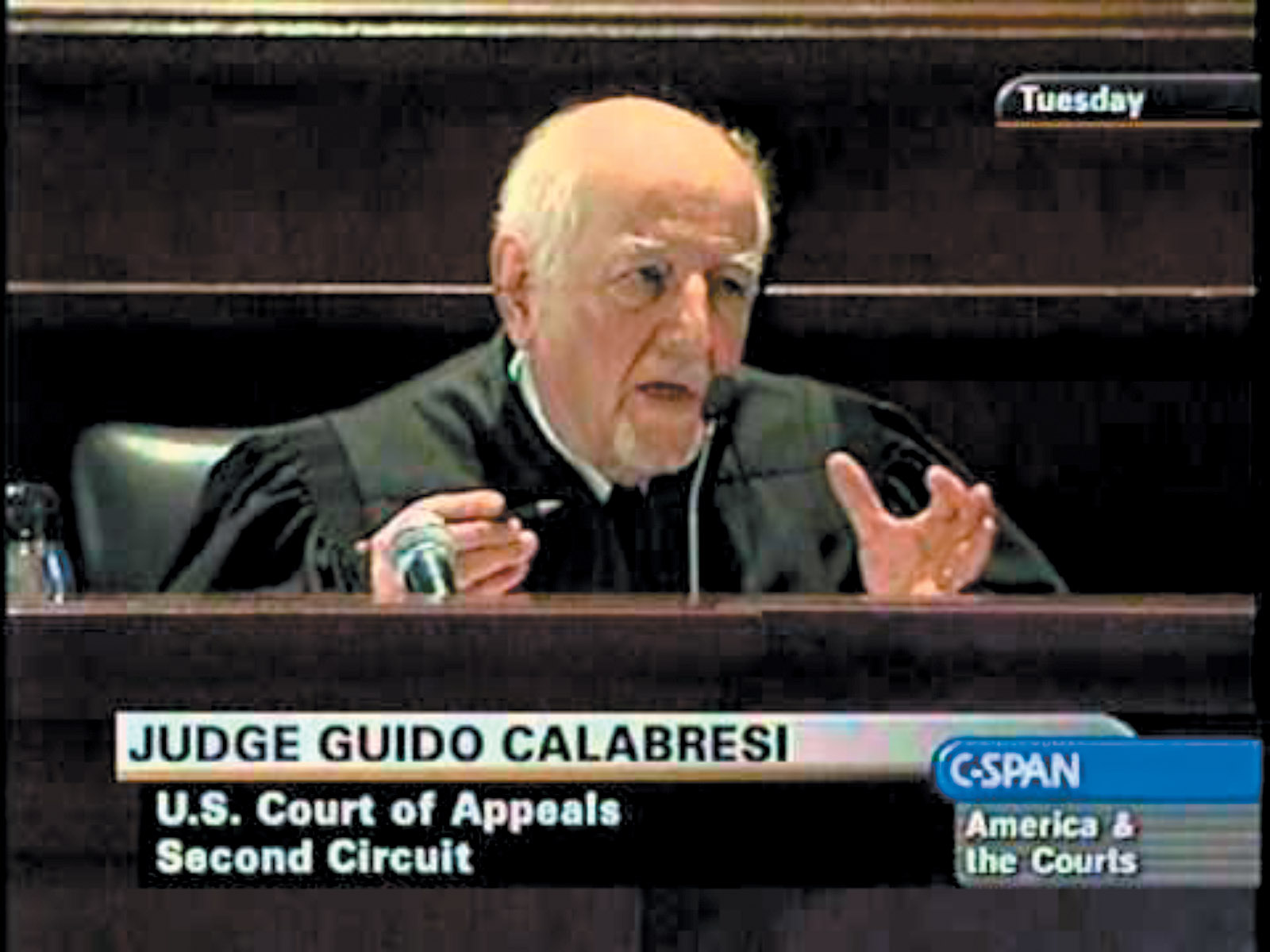

Judge Guido Calabresi during arguments in Arar v. Ashcroft, New York City, December 2008. The court ruled that Maher Arar—a Canadian citizen who was wrongly deported by the US to Syria, where he was held for a year and subjected to torture—had no right to sue US government officials. In his dissent, Calabresi argued that ‘when the history of this distinguished court is written, today’s majority opinion will be viewed with dismay.’

Since its start in the 1960s, the field of “law and economics” has revolutionized legal thinking. It might well count as the most influential intellectual development in law in the last hundred years. It has also had a major impact on how regulators in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere deal with antitrust, environmental protection, highway safety, health care, nuclear power, and workers’ rights. But from the beginning the entire field has contained a major fault line, sharply dividing two schools of thought: the Chicago School and the Yale School.

The Chicago School, led by Judge Richard Posner, regards economics as a kind of spotlight, enabling us to see legal problems far more clearly than we otherwise would. Posner’s main goal has been to use economic tools to identify the real-world consequences of different legal rules.1 Suppose, for example, that a cement factory emits noxious fumes, causing illnesses in nearby families. With the help of economics, Posner asks: What would be the effects of different legal rules on the likelihood that people will take remedial action? If the law requires the cement company to compensate the families, it might scale back its operations or even close them down. That might be a good thing, because it will prevent illnesses, but it might also have harmful consequences if it means that the cost of cement will increase or that a lot of workers will lose their jobs.

In this situation, economics can help us to identify the relevant tradeoffs. Posner thinks that courts should reject the families’ effort to shut down the cement factory if the health benefits turn out to be lower than the total economic costs. (Of course, it may not be so easy to turn the health benefits into monetary equivalents; there is an extensive economic literature on that question.2)

Posner himself dislikes the term “law and economics,” and he has long preferred to speak of the “economic analysis of law.” This is not just a matter of semantics. To the Chicago School, the idea of “law and economics” sounds impossibly murky. What’s that “and” about, anyway? The Chicago School thinks that economics helps to specify the effects of the law in the real world, by showing (for example) that potential criminals are affected by both the severity and the likelihood of punishment, and that large increases in the minimum wage might decrease employment (by making it more expensive to hire people). Legal rules—governing workplace injuries, the environment, copyright, formation of contracts—are merely objects of study.

Members of the Chicago School also like free markets a lot, and they are suspicious of any and all legal rules that interfere with them. They want more trading in markets, not less. For example, Posner has written that “a market in kidneys should be permitted. The ‘repugnance’ that the idea of selling body parts engenders in many people seems to me to have no rational basis.” He has also argued for deregulating the market in adoptions, arguing that we should facilitate “legal baby selling.”

The Yale School is keenly interested in the consequences of law as well. As a young professor at Yale Law School, Guido Calabresi argued, in a series of articles and in his book The Cost of Accidents: A Legal and Economic Analysis (1970), that courts should give careful consideration to the costs and benefits of legal rules, and that an understanding of economics can help them to undertake that consideration. But unlike Posner, Calabresi emphasizes that economists can learn from law. For example, they might learn how people think about equality, and they might also learn that some things should not be traded on markets at all. For this reason, Calabresi warmly embraces the phrase “law and economics,” which suggests that the two fields are being brought into contact.

Now in his eighties, Calabresi has elaborated this vision of law and economics for the first time in The Future of Law and Economics. To situate his argument, he invokes John Stuart Mill, who famously criticized one of his heroes, Jeremy Bentham, for approaching human life as a kind of visitor from another planet, equipped with the single tool of utilitarianism, according to which rightness or wrongness is determined by asking whether an action will cause more pleasure to those affected by it than any alternative would. Mill thought that Bentham was like a one-eyed man, a “systematic half-thinker,” who saw things that no one else did but who lacked something like depth perception. He failed to see, Mill argued, that “some kinds of pleasure are more desirable and valuable than others.” Calabresi thinks that the Chicago School is a bit like that, in the sense that it too lacks depth perception, failing to see the value of equality and of ensuring that some things not be traded at all.

Advertisement

It is important to understand that unlike other prominent critics of the Chicago School, such as Ronald Dworkin,3 Calabresi is a committed practitioner of law and economics, indeed a founder of the field, and he works broadly within the utilitarian tradition. He does not argue that people have rights that must be respected, whatever the outcome of a utilitarian calculus. (Whether or not he believes that, it is not his argument.) But he cherishes law, seeing it as a precious repository of hard-won social wisdom, and he thinks that economists should treat it as such. He objects that they do not approach legal rules with sufficient respect and that they fail to treat them as products of insight and experience.

Through legislation, regulation, and court decisions, Calabresi argues, law may shape our values—sometimes by promoting principles of nondiscrimination, sometimes by discouraging pollution, and sometimes by promoting shared experiences (for example the opportunity to visit parks and museums, by making that opportunity freely available to all). Calabresi does not, of course, deny that the law might not entirely succeed in shaping values. Brown v. Board of Education was decided in 1954, and the civil rights laws were enacted a decade later, but certainly racism persists.

Calabresi’s only point is that we will be unable to understand some of the most important aspirations of the legal system if we do not see that people’s preferences and values can be malleable—and are sometimes a product of the legal system itself. The Chicago School, by contrast, often tends to see people’s preferences as fixed, even innate, so that they are not a product of, and cannot be changed by, law.4 More broadly, Calabresi insists that we all have a lot to gain from a careful investigation of what law actually does.

Calabresi’s principal example involves “merit goods,” which he understands to mean those goods that, by social consensus, should not be traded on any market. (Recall that the Chicago School is skeptical of the whole idea of preventing trades.) For some goods, such as life itself, people object to pricing as such. What’s a human life worth? $5 million? $20 million? If courts were to put a price on human life, Calabresi says, they would make people suffer, because they would impose “external moral costs”—feelings of outrage, for example—on those who believe that any such pricing is a serious moral wrong.

It is true that in a wrongful death action, courts might award family members compensation for lost earnings—but Calabresi argues that that’s altogether different from saying that the deceased was “worth” a certain amount. He insists that if a person is hurt or killed in an accident, the tort system “does not speak of what it does as pricing lives or safety.” Instead “the rubric is always that of compensating victims, of redressing wrongs,” or of “returning the victim to the status quo before the accident.”

For other goods, we may not object to prices as such, but most people—unlike some members of the Chicago School—don’t want to use the market for them, because doing so would ensure that their allocation would be determined by people’s wealth. (Recall the sale of kidneys.) For such goods, our rejection of the market comes from our concerns about economic inequality. It is important to see that Calabresi is not, in this book, attempting to take a stand on inequality, or to say how the law might reduce it. He does not, for example, engage with Thomas Piketty’s work.5 His concern is very specific. In the presence of widespread inequality, most people do not want the market to be allowed to allocate certain goods.

Calabresi argues that these goods include the right to obtain body parts, military service, and the right to influence elections through campaign contributions. They might also include the right to minimum levels of education, medical care, and environmental protection. Calabresi urges that all of these

bring forth the same reaction in a large number of people—namely, the feeling that these are not things either that the rich should be able to get (or avoid) simply because they are rich or that the poor should be led to give up (or bear) just because of their poverty.

Calabresi is less interested in justifying that reaction than in the simple fact of its existence. Where Posner favors use of the market, Calabresi stresses that putting such goods on the market would tell “the rest of us something about how unequal our wealth distribution is, something that we are, literally, pained to hear.” People “feel much better if some goods are made available to those who ‘need’ them, regardless of wealth and regardless of whether they would forego [sic] them in exchange for more wealth.”

Advertisement

Calabresi notes that the law honors these “deeply held attitudes,” and he thinks it is right for it to do so; writers such as Posner, he suggests, would do well to respect them in making judgments about what the law should do. Societies have adopted nonmarket alternatives for allocating merit goods, such as lotteries (for military service), rationing systems (for bodily organs), economic subsidies (for education and health care), and regulatory commands (for clean air). What economists fail to consider is that some people prefer markets, while others prefer commands (such as regulatory mandates to reduce pollution).

While chiding economists on this point Calabresi argues, in one of his most suggestive discussions, that they should be willing to favor some tastes over others. Suppose that we indulge an innocuous-seeming assumption: more is usually better than less. If so, then societies should cultivate “any tastes or values that increase the desire for things which are in common supply in that society—for things that are not scarce.” If, for example, a city has a large, beautiful park, it should promote people’s interest in visiting that park.

That’s an intriguing claim, but Calabresi might have been more careful here. It might not be desirable to cultivate tastes for many goods that are in common supply; consider high-calorie candy bars, French fries, or violent pornography. Calabresi’s argument makes most sense if he is understood to be saying that we should promote tastes for goods that are easy to get—but not if there is an independent reason, moral or otherwise, against promoting them.

Calabresi also emphasizes the importance of “the desire to create,” because of the many social benefits produced by that desire. He points to the value of “relatively informal artistic activities” through which diverse people can be creative, even if they are not especially talented—such as local choirs, karaoke, handicrafts, and home cooking. He is particularly concerned about the devaluation of child-rearing, which undermines people’s desire to engage in what he sees as a genuinely creative activity. He thinks that societies should give serious consideration to “laws that promote the desirability of engaging in child rearing.” Paid parental leave is an example.

Calabresi is persuasive in arguing that economists (and the rest of us) can learn a lot from careful investigation of what legal systems actually do, for example in providing for common spaces, such as parks and museums. One reason is that the law has to deal with so many particulars, which can force people to reassess any abstract theory. You might think, for example, that there is an absolute right to freedom of speech, but once you encounter cases that involve threats, perjury, bribes, false advertising, and extortion, you might end up with a more refined understanding of what speech is and isn’t protected. And Calabresi is right to suggest that the law may go in directions that confound members of the Chicago School.

In the prominent 1989 case of Ohio v. Department of Interior, for example, a federal court rejected the government’s claim that compensation for damage to a natural resource (such as a pristine area with marine mammals) should be limited to the market value of that resource. In the court’s view, the real value of such a resource is not captured by its mere market value; the worth of a “seals and seabird habitat” is not “measured by the market value of the fur seals’ pelts.” If you care about seals, you’ll find that conclusion convincing, and even if seals do not matter to you, you might agree that the value of a precious natural resource is not equivalent to the amount that people would be willing to pay to use it.

At the same time, I am not persuaded by many of Calabresi’s arguments about merit goods; most of his examples do not seem to work. The legal system generally sides with Chicago, not Yale, because it is willing to monetize goods and to allow a lot of trading. For example, legally established government agencies put an economic value on life all the time. As Calabresi is aware, agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Transportation have long had specific figures for the “value of a statistical life,” and they use that value to decide how stringent regulations should be.6 In current dollars, the standard number is around $9 million. Nor do agencies pull that number from the sky. In using cost-benefit analysis to decide whether to issue safety or health regulations, they rely mostly on economic studies in the United States, which find that on average workers receive about $90 to face a mortality risk of 1 in 100,000 (from, say, on-the-job accidents). With a little multiplication, you get that $9 million figure. In situations that involve air pollution, highway safety, and occupational hazards, regulators often deal with risks in the vicinity of 1 in 100,000, and when they say that a statistical life is worth $9 million, they are building on those labor market studies.

You can ask a lot of questions about that practice. For example, should federal regulators really be using a single number, based on the average amount that workers receive? Should a mortality risk of 1 in 100,000 from dirty air, unsafe food, or terrorism be valued the same as a mortality risk from on-the-job accidents?7 That’s a fair question, but for present purposes, the only point is that modern practice is inconsistent with Calabresi’s suggestion that our legal system refuses to price life as such, or that our society forbids such pricing. On the contrary, the pricing is done openly and transparently, and by officials who have been confirmed by the US Senate and who work for the president of the United States (and are thus far more accountable to the public than courts).

Calabresi’s claims about other “merit goods” seem to elide some important distinctions. For some of those goods, many people in the US don’t really object to the use of markets; they argue only that everyone deserves a decent minimum. (Admittedly, this is a vague concept, and people disagree about how to specify it.) You are entitled to a high school education, medical help, and clean air even if you don’t have much money. Indeed, Bernie Sanders has proposed free tuition to public colleges and Hillary Clinton has proposed “debt-free” tuition through substantial increases in subsidies; many people evidently believe in an educational entitlement that goes beyond high school. But it is one thing to say that everyone has the right to some kind of minimum. It is quite another to accept Calabresi’s particular claim, which is that certain goods should not be traded on markets at all. In the United States, at least, wealthy people are allowed to pay for private education, the best doctors, and homes in pristine areas near the beach, and no one is trying to forbid them to do those things.

Campaign contributions raise different issues, and the law is not now with Calabresi. As he knows, the Supreme Court essentially ruled, in the Citizens United case, that the Constitution gives corporations a right to spend whatever they want on political campaigns. For those who think that the Court was wrong, the objection is very specific: disparities in wealth shouldn’t be turned into disparities in political power. If you’re rich, you’re allowed to buy fancy cars, vacations, and clothes—but not governments. Those who favor restrictions on campaign contributions are objecting to what they see as a form of corruption, defined as a practice by which contributors end up buying candidates and their votes. That’s a serious problem, but it is not clear that it involves Calabresi’s general category of “merit goods.”

Calabresi’s most plausible example of a merit good involves bodily organs. The law forbids people to buy and sell kidneys, and one reason does involve inequality: it’s gruesome to think of poor people walking around with fewer organs because rich people have made them an offer they can’t refuse. If you have only one kidney, your life and health are in far greater danger than if you have two. But economists (and others) raise a legitimate question about bans on organ sales8: If poor people are willing to sell their kidneys because they need the money, do we really help them by forbidding the sale? Behavioral economists worry that some people would sell organs impulsively and without sufficient reflection about the long-term health consequences. But that’s not Calabresi’s point about the moral compunctions of observers. It’s a suggestion that where the long-term consequences are very serious, it might be legitimate to forbid people to engage in behavior that they will eventually regret and from which they might suffer and die.

Calabresi thinks that economists are inconsistent in saying that they will respect people’s values and tastes, while also disregarding people’s moral outrage when certain goods are traded on markets. But I wonder if there’s a deep problem there. Economists can borrow from a prominent strand in the liberal tradition and argue that by itself, moral revulsion about the behavior of other people is not a legitimate reason to regulate their conduct. Suppose that observers are deeply offended when people buy and sell the works of Karl Marx, rent property to same-sex couples, purchase access to car pool lanes, or make movies about cars crashing into other cars. As Mill argued, there are good utilitarian reasons for concluding that mere offense isn’t a sufficient reason for controlling what people do. If authorities could regulate behavior whenever it offended them, we’d block a lot of trades, and people would end up a lot worse off. Some people would invoke fundamental rights here, and argue that whatever the outcome of utilitarian calculations, people have the right to read whatever they want and to sell their organs or anything else to whomever they want—and the concerns of third parties just don’t matter.

Surprisingly, Calabresi does not explore an objection that might well have strengthened his central argument. Many people insist that museums, theaters, libraries, parks, playgrounds, and legislatures should not charge for admission, on the ground that they provide important civic functions, which would be undermined if visits were open only to people who would pay enough.9 Law and economics could learn a great deal by investigating how both social norms and law create domains in which economic trades are not allowed to occur; a shared civic culture, beneficial to rich and poor alike, may well depend on some such restrictions. (Military service was among such activities in the US until the draft was eliminated.)

This point is closely connected with Calabresi’s important suggestion that economists should be willing to say a lot more about the need to encourage certain tastes and to discourage others. When Calabresi began his career in the 1960s, that suggestion would have seemed anathema within the economics profession, even a form of sacrilege. The whole point of economic analysis was to take people as they are, not as they should be. But over the last thirty years, many social scientists have been interested in exploring when and how law shapes people’s preferences. Suppose that the legal system bans hotels from discriminating on the basis of sexual orientation, or requires municipalities to maintain public parks, theaters, and museums, open to all and free of charge. If so, these requirements might well alter citizens’ values. In fact that is one of the major purposes of laws forbidding discrimination and maintaining public spaces.

Calabresi is generally correct, and subtly moving, when he argues for the immense importance of promoting “tastes or values that increase the desire for things which are in common supply.”10 By encouraging shared activities and uses of publicly funded institutions, many states and localities have been trying to do exactly that. For example, the city of New York has a considerable budget for public libraries. In an age of fragmentation, it is legitimate, and not unrealistically optimistic, to insist that the legal system can help cultivate people’s appreciation for experiences and goods, and for forms of creative self-expression, that are available to everyone. A fuller understanding of that point could greatly enrich economic theory11—and social life as well.

This Issue

November 10, 2016

Inside the Sacrifice Zone

Why Be a Parent?

Kierkegaard’s Rebellion

-

1

See Richard A. Posner, Economic Analysis of Law (Wolters Kluwer Law and Business, 2014), 9th edition. ↩

-

2

See W. Kip Viscusi, Fatal Tradeoffs: Public and Private Responsibilities for Risk (Oxford University Press, 1992). ↩

-

3

See Dworkin’s classic essay, “Is Wealth a Value?,” The Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 9, No. 2 (March 1980). ↩

-

4

Some members of the Chicago School take a broader perspective. See Gary S. Becker, Accounting for Tastes (Harvard University Press, 1998). ↩

-

5

See Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Belknap Press/Harvard University Press, 2013); reviewed in these pages by Paul Krugman, May 8, 2014. ↩

-

6

Agencies often use cost-benefit analysis to decide on the appropriate level of stringency. Suppose, for example, that an automobile safety regulation would cost $800 million and is expected to save 100 lives. If a statistical life is valued at $9 million, the regulation would be justified, because it would have $100 million in “net benefits.” ↩

-

7

This question, and related ones, are discussed in my Valuing Life: Humanizing the Regulatory State (University of Chicago Press, 2014). ↩

-

8

See Janet Radcliffe Richards, The Ethics of Transplants: Why Careless Thought Costs Lives (Oxford University Press, 2012). ↩

-

9

Michael Sandel has developed this argument in some detail. See What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012). ↩

-

10

Recall, however, that the argument must be qualified: we probably would not want the legal system to be promoting a taste for cheap but unhealthy food. ↩

-

11

For important steps toward that enrichment, see Michael Suk-Young Chwe, Rational Ritual: Culture, Coordination, and Common Knowledge (Princeton University Press, 2001). For a general discussion, see Edna Ullmann-Margalit and Cass R. Sunstein, “Solidarity Goods,” The Journal of Political Philosophy, Vol. 9, No. 2 (2002). ↩