Collection Jean-Christophe Castelli/©Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

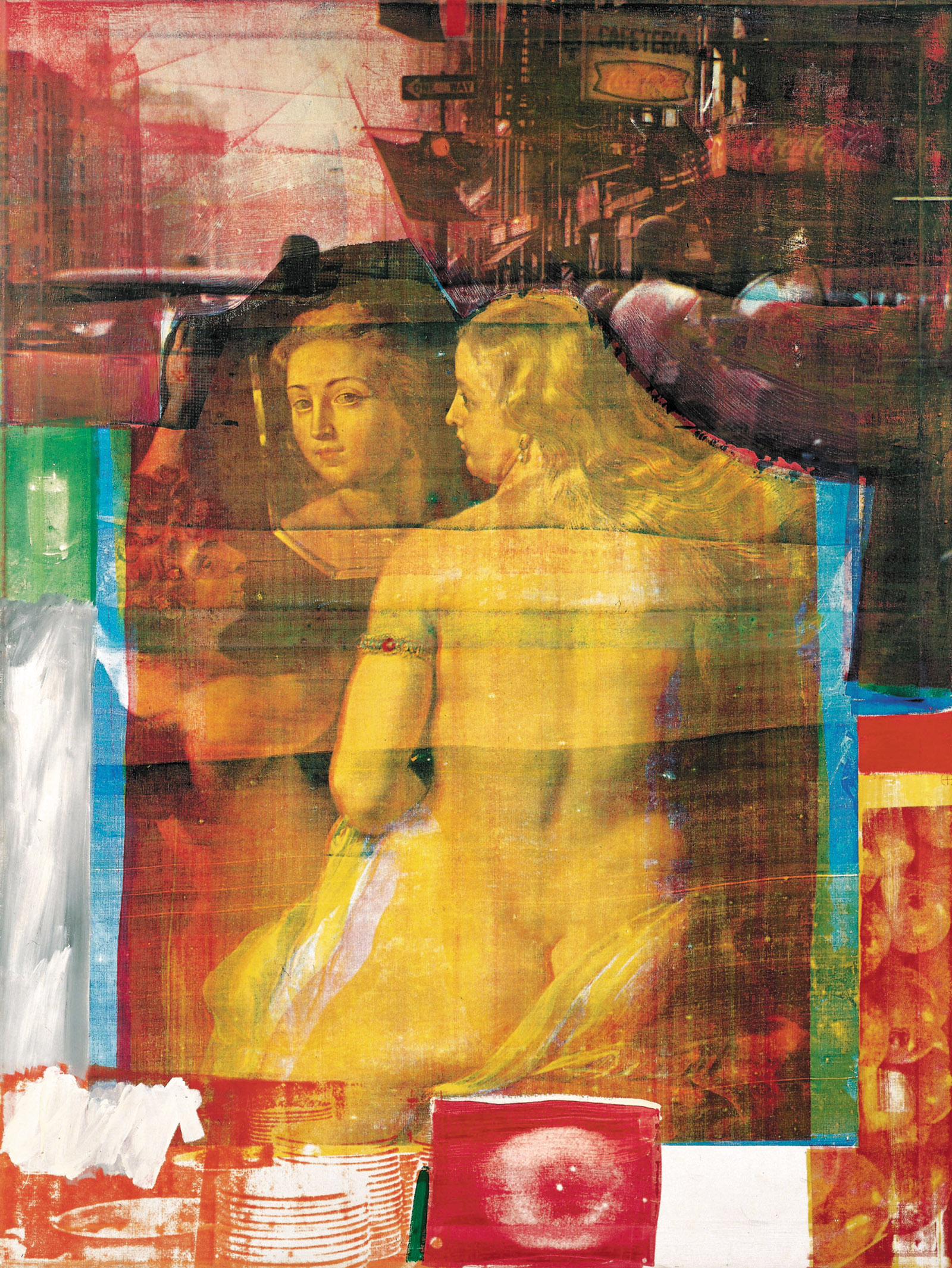

Robert Rauschenberg: Persimmon, 1964; from Rauschenberg’s series of oil and silkscreen-ink print paintings in which, Jed Perl writes, ‘photographs of President Kennedy, crowded city streets, space travel, and a nude by Rubens come together to suggest a modernized version of the emotional fireworks we know from Baroque altarpieces.’

Robert Rauschenberg was a showman, a trickster, a shaman, and a charmer. In the retrospective that recently closed at Tate Modern in London and will be arriving at the Museum of Modern Art in New York this May, museumgoers are confronted with many different things: the imprint of an automobile tire; a couple of rocks tied with pieces of rope or string; paintings that are all white, all black, or all red; a sheet and pillow spattered with paint; a drawing by Willem de Kooning that Rauschenberg erased; deconstructed corrugated cardboard boxes; bright silken banners; a blinking light; a taxidermied Angora goat; mixed-media works mounted on wheels so as to be easily moved around; and paintings packed with photographic images. Rauschenberg’s career is the fool’s errand of twentieth-century American art. That his errand earned him the highest honor at the 1964 Venice Biennale, the Grand Prize for Painting, and major exhibitions and retrospectives at the Stedelijk, the Guggenheim, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and now Tate Modern and MoMA amounts to nothing more than confirmation of what fools we mortals be.

There is little mystery as to why Rauschenberg, who died in 2008 at the age of eighty-two, was a success from the very beginning of his career in the 1950s. Gallerygoers and museumgoers have had a taste for avant-garde escapades and hijinks at least since New Yorkers went to gawk at what many regarded as the follies of modern art in 1913, when the Armory Show opened in Manhattan. Marcel Duchamp, whose Nude Descending a Staircase caused an uproar there, was friendly with Rauschenberg by 1960, when Rauschenberg was cultivating a rather Duchampian reputation as an easygoing, seductive enfant terrible. Rauschenberg became adept at keeping admirers and detractors alike on their toes with his swaggering insouciance and Delphic-Dadaist remarks. He was in sync with a time when Dadaism was moving into the mainstream and more and more artists were interested in what the critic Harold Rosenberg dubbed the “de-definition of art.” “Nothing is left of art,” Rosenberg wrote, “but the fiction of the artist.”

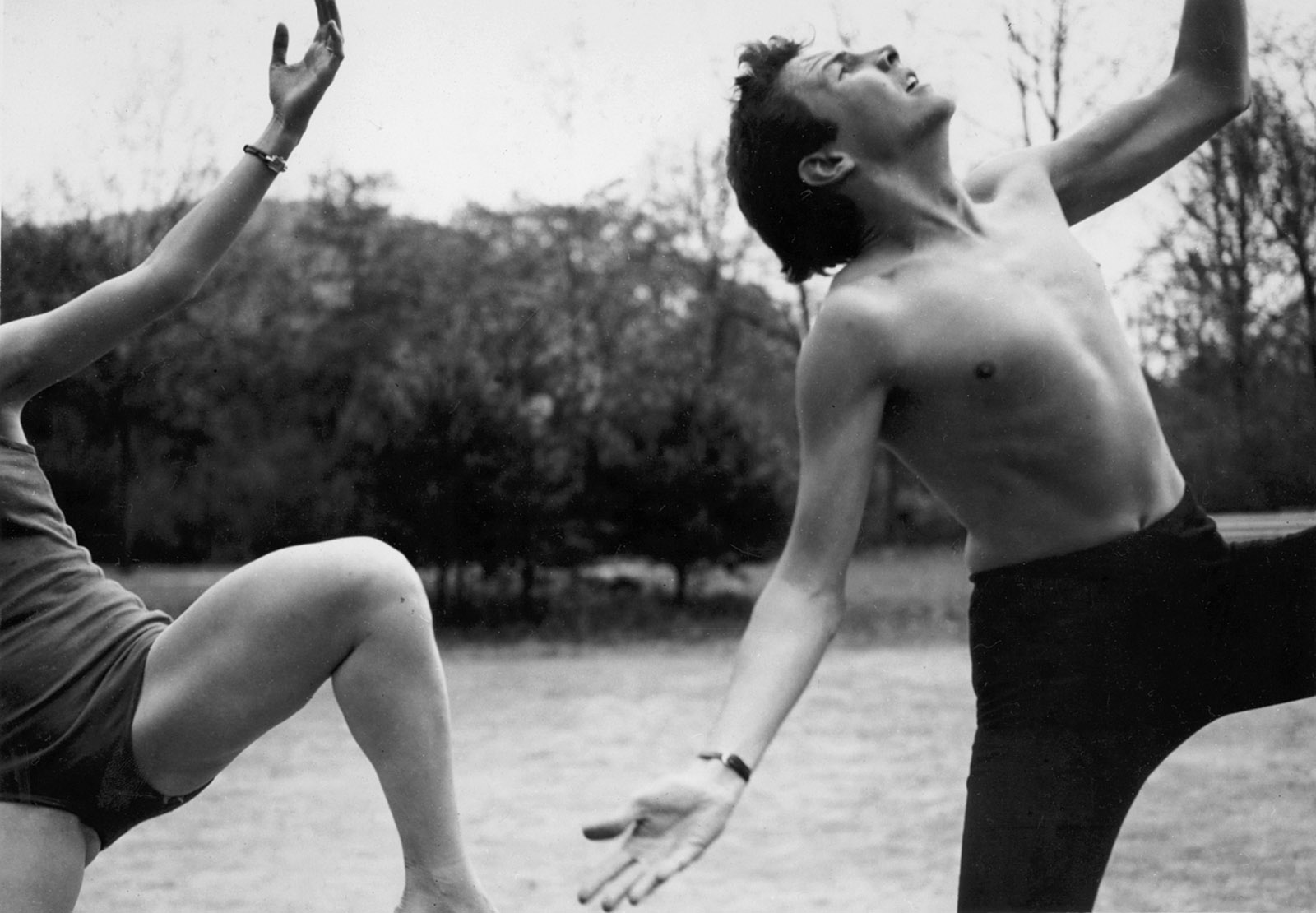

When it came to de-defining art, Rauschenberg’s attitude was that if painting wouldn’t do the trick, he would do something else. Whatever he did or didn’t do, he would remain an artist. While still a student in the early 1950s at Black Mountain College, that redoubtable laboratory for experimentation in the arts, he was photographed in a dance performance with Elizabeth Schmitt Jennerjahn, who was teaching at the school. That image of the young, dashing, bare-chested bohemian—head held high and arms spread wide, as if in exaltation—is reproduced on a full page early in the exhibition catalog. And why not? Some of the storied episodes in Rauschenberg’s later career transpired not in art galleries but in performance spaces, where he not only planned the shows and made the sets, but on a number of occasions in the 1960s was one of the performers.

Rauschenberg would do whatever it took to destabilize the audience’s expectations. The curators of the current retrospective—Leah Dickerman of MoMA and Achim Borchardt-Hume of Tate Modern—can do little more than stage-manage the goings-on. Dickerman is an outstanding scholar of twentieth-century art whose work in exhibitions devoted to Dada, the Bauhaus, the early history of abstraction, and the murals of Diego Rivera sets a very high standard. That she has nothing of much significance to say about Rauschenberg in the essay with which the catalog closes says less about her than about him.

It was as a genre-buster—an artist who crossed boundaries and cross-pollinated disciplines—that Rauschenberg was embraced in the 1960s. More than fifty years later, there are more and more artists who seem to believe, as he apparently did, that art is unbounded. The only difference is that our contemporaries—figures such as Jeff Koons, Isa Genzken, and Matthew Day Jackson—have traded his whatever-you-want for an even more open-ended and blunt whatever. A creative spirit, according to the argument that Rauschenberg did so much to advance, need not be merely a painter, a photographer, a stage designer, a printmaker, a moviemaker, a collagist, an assemblagist, a writer, an actor, a musician, or a dancer. An artist can be any or all of these things, and even many of them simultaneously. The old artisanal model of the artist—the artist whose genius is grounded in the demands of a particular craft—is replaced by the artist who is often not only figuratively but also literally without portfolio, a creative personality-at-large in the arts.

Advertisement

One can argue that there are historical precedents for this view. Picasso enriched both his painting and his sculpture by working back and forth between the two disciplines. And the work that Picasso did in the theater certainly precipitated significant shifts in his painting. Such cross-fertilization is by no means only a modern phenomenon. In the seventeenth century, the English diarist John Evelyn saw a theatrical production in Rome masterminded by Bernini, who apparently didn’t feel it was enough to be a painter, a sculptor, and an architect, but also, as Evelyn put it, “painted the scenes, cut the statues, invented the engines, compos’d the musiq, writ the comedy, and built the theatre.”

Cross-pollination is all well and good. The question is where it takes the artist. For Picasso, the embrace of a range of creative disciplines—and the mixing of disciplines and in some instances the destabilization of disciplines—returned him, refreshed, to the revitalization of a particular discipline. Picasso’s great friend Guillaume Apollinaire was thinking about all of this when he wrote, in his poem “The Pretty Red-Head,” of “this long quarrel of tradition and innovation/Of Order and Adventure.” Apollinaire insisted that there was no final resolution to this quarrel. He asked that we be “indulgent” with those who question “the perfection of order,” considering that they “offer you vast and strange domains.” He asked “pity” for those who “fight always in the front lines/Of the limitless and of the future/Pity our errors pity our sins.”

Apollinaire saw a need for both those vast, strange domains and for order and perfection. So it was with Picasso, who embarked on his greatest adventures—the movements from closed to open sculptural form, from representation to abstraction and back, from the studio to the stage, from Surrealism to Neoclassicism—with a sense of how each fresh adventure renewed his appreciation of the old order and the old perfection.

The trouble with Robert Rauschenberg is that adventure and innovation invariably confound order and tradition. Didn’t it ever occur to him that the search for perfection, however quixotic, is among the greatest adventures? Although this overstuffed show offers only a partial view of Rauschenberg’s megalomaniacal output—among the many embarrassments wisely overlooked is a series of bicycles edged with neon from the early 1990s—there are enough twists and turns to leave museumgoers in confusion. From what I could see when I visited Tate Modern on a weekday afternoon, visitors were intrigued, beguiled, baffled, bewildered, and sometimes just plain bored.

There’s a feeling of bumper cars about the entire show, and almost literally when you come to Oracle (1962–1965), a group of assemblages including an exhaust pipe, a typewriter table, a ventilation duct, a wire basket, and some crushed metal, all mounted on wheels. And what is one to make of Mud Muse (1968–1971)—on which Rauschenberg worked, as he did on Oracle, with a number of collaborators—which features a substance known as bentonite bubbling up in a room-sized aluminum-and-glass vat? You can almost hear a voice announcing: “It’s showtime, folks!”

It was in 1959, for the catalog of the exhibition “Sixteen Americans” at the Museum of Modern Art, that Rauschenberg dreamed up what has become his most famous statement. “Painting,” he announced, “relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in that gap between the two.)” It’s difficult to conceive of a more gnomic twenty-one-word declaration of principles. What on earth is Rauschenberg talking about? What does it mean to say that art can’t be “made”? And what is that “gap” between “art and life” aside from the sweet spot where Rauschenberg established his reputation? An artist can no more actually operate in the gap between art and life than a magician can actually cut a woman in half and have her come out whole.

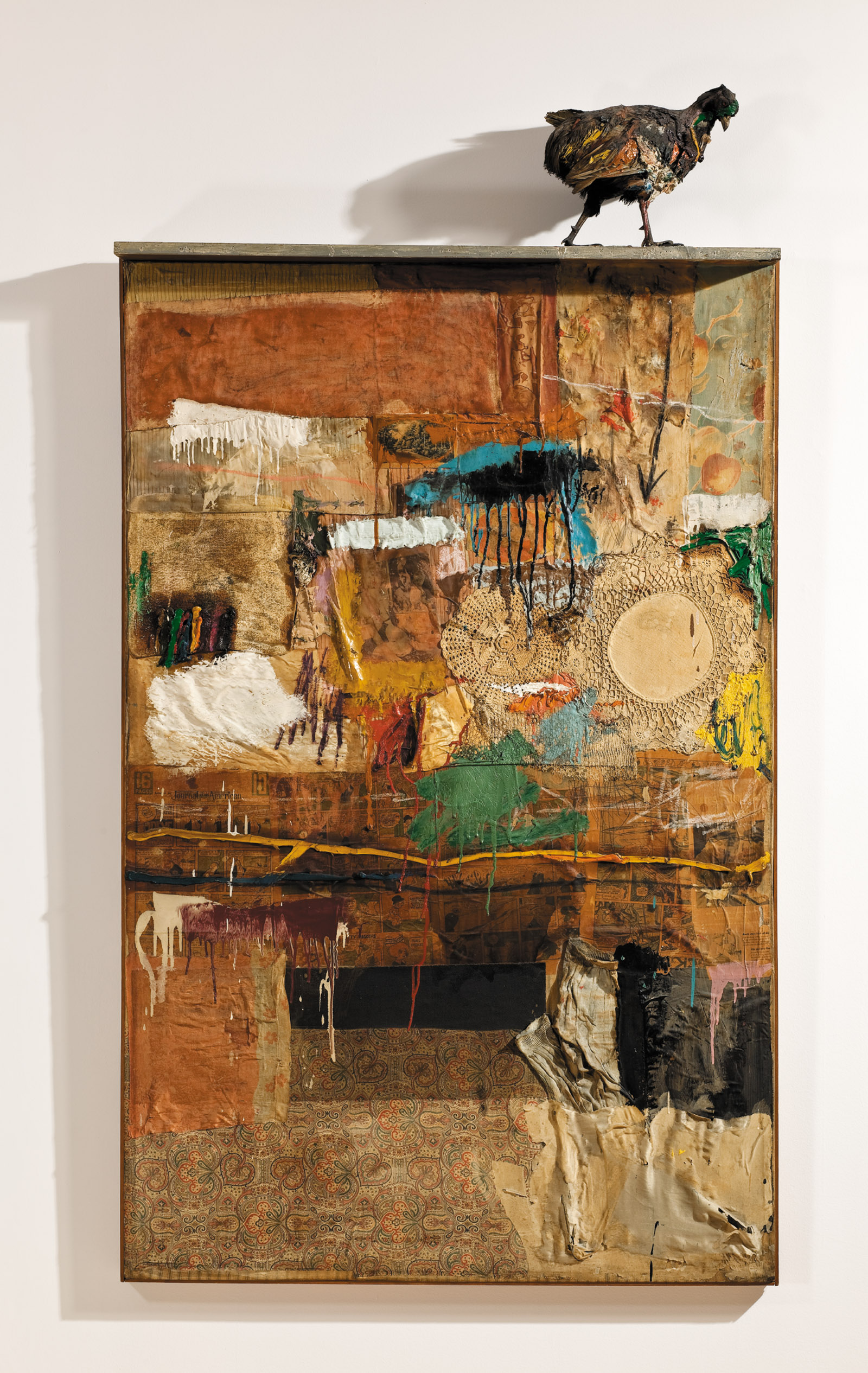

Speaking of the mixed-media constructions that Rauschenberg called Combines, Jasper Johns (his lover for a time) remarked that they were “painting playing the game of sculpture.” The trouble with Johns’s characterization is that the Combines don’t even begin with painting. Rauschenberg is fundamentally a mixed-media guy. The basic impulse behind the Combines is the impulse of a collagist or an assemblagist, not a painter. Rebus (1955), which hangs more or less flat on the wall (i.e., in the manner of a painting), includes printed paper, newspaper, poster clippings, comic strips, fabric, and a drawing by Cy Twombly, among other items. The Combines begin with a rejection of the conventions of painting, so that when Rauschenberg moves into the third dimension with the taxidermied pheasant atop Satellite (1955) or attaches a wooden door to the structure in Interview (1955), he’s simply upping the ante in collage. The artist who might be said to have created works in which painting plays the game of sculpture is Picasso. But he was able to remake the rules of the game only because he had mastered them in the first place, which Rauschenberg never did.

Advertisement

If there is a constituency that never wearies of the games Rauschenberg plays, it’s curators, critics, journalists, and historians. They’ve chronicled his every move. Many years ago, Calvin Tomkins grasped the almost novelistic fascination of the man and his career. He wrote about Rauschenberg in The New Yorker and published two books that delved into the showman’s doings: The Bride and the Bachelors: The Heretical Courtship in Modern Art (1965) and Off the Wall: Robert Rauschenberg and the Art World of Our Time (1980).

It may be the distinguished art historian Leo Steinberg who first made the argument that the showman was also a deep thinker. Rauschenberg became the centerpiece of what remains Steinberg’s most famous essay, “Other Criteria,” which began as a lecture at MoMA in 1968. In the late 1960s Steinberg was looking for a way beyond what he believed was Clement Greenberg’s overly prescriptive view of painting’s possibilities. In Rauschenberg’s work he saw the outlines of a principle that he dubbed “the flatbed plane.” The painting became “a surface to which anything reachable-thinkable would adhere. It had to be whatever a billboard or dashboard is, and everything a projection screen is.” He argued that “Rauschenberg’s work surface stood for the mind itself—dump, reservoir, switching center, abundant with concrete references freely associated as in an internal monologue.”

In a work such as Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit (1955), the elements certainly do have a stream-of-consciousness coherence. Short Circuit includes, among other items, notebook paper, a postcard, printed reproductions of Abraham Lincoln and a fifteenth-century painting of Venus by Lorenzo di Credi, an autograph of Judy Garland, and a program from an early John Cage concert. But a stream-of-consciousness coherence is not necessarily an artistic coherence. James Joyce and Virginia Woolf used stream-of-consciousness techniques to produce verbal music. Rauschenberg’s stream-of-consciousness remains visually inert.

The flatbed picture plane, as Steinberg describes it, is indiscriminate. The artist opts out of that most essential artistic activity—which is the necessity to discriminate, to choose. Artists aren’t pushed to remake or reimagine images, experiences, and ideas; they’re just meant to receive them. Rauschenberg’s indiscriminateness—at times it suggests passivity—may be part of his appeal, at least for the theoretically inclined. When he flirted with a conventional literary program in the series of works on paper illustrating Dante’s Inferno (1958–1960), he left enough mixed messages to provoke more than one interpretation. The interpreters have had a field day with some of the Combines, especially Monogram, the work from 1955–1959 that features a taxidermied Angora goat with a tire stuck around its midriff. Robert Hughes described it as “an image of anal sex, the satyr in the sphincter.” Some have agreed.

But Steinberg, in “Encounters with Rauschenberg,” a lecture he gave in the late 1990s, worried that the specificity of such an interpretation threatened to hamstring what he called the work’s “definitive incongruity.” He cited approvingly two scholars who argued that Rauschenberg’s “works invite decodification, but frustrate its operation.” Perhaps what has made Rauschenberg’s work such an appealing subject for art historians—including figures much admired in the field, among them Rosalind Krauss and Yve-Alain Bois—is the extent to which it invites interpretation even as it ultimately lets the interpreter off the hook. We have moved beyond Susan Sontag’s early pronouncements against interpretation to something more like no-fault interpretation.

What Rauschenberg provides his interpreters is a nearly endless succession of whims, gambits, riffs, and diversions. Many of his effects amount to little more than lessons everybody ought to have learned in Modern Art 101. His use of asymmetry, juxtaposition, and accident can feel rote and perfunctory. Is there anything especially interesting about hanging a wooden chair on a canvas, as he did in Pilgrim (1960)? Is there much of anything he does in the way of collage that Kurt Schwitters hadn’t done a couple of generations earlier?

The only point in the retrospective where the energy level struck me as rising was with the group of silk-screen-ink print paintings Rauschenberg made between 1963 and 1964, in which photographs of President Kennedy, crowded city streets, space travel, and a nude by Rubens come together to suggest a modernized version of the emotional fireworks we know from Baroque altarpieces. Rauschenberg marshals his images with some flair in these canvases, particularly Retroactive I and II and Persimmon (all 1964). He telegraphs the period’s jittery high spirits. But elsewhere his effects are mostly either chilly and undercooked or steamy and overcooked. Some of the works with collage elements from the 1950s, such as the nine-foot-wide Charlene, have unpleasantly thickened surfaces that feel gummed-up, lacquered, gelatinized.

For Rauschenberg’s admirers, his work may have some of the fascination of T.S. Eliot’s “fragments I have shored against my ruins.” The critics and historians who minutely examine each element in the Combines approach their material with many of the same analytical tools used by scholars as they pore over bits and pieces of ancient papyrus. In an essay in the catalog of the show, Branden W. Joseph observes of some elements in Gloria (1956) that the combination of several poster fragments and duplicated newspaper fragments “produce[s] a pun on Gloria Vanderbilt’s second divorce and third marriage.” As for museumgoers, they become archaeologists of a sort, exploring the detritus of the recent past. Much of what is in the Rauschenberg retrospective amounts to mementoes, souvenirs, documents.

Sometimes this is literally the case, for a number of galleries in the exhibition are devoted to reconstructions of performances and collaborations with which Rauschenberg was involved over the years. Especially in the first half of his career, his work was intertwined with a series of close partners in art and life. The first of these collaborators was his wife, the painter Susan Weil, with whom he made a series of photographic experiments using exposed blueprint paper. In the years after their separation, Rauschenberg was intimately involved with the painters Cy Twombly and Jasper Johns and the dancer Steve Paxton. Rauschenberg’s theatrical experiments and collaborations are the most engaging aspects of the show.

Rauschenberg, who is little more than a cipher in his paintings and sculptures, leaves an impression as a stage performer in a couple of projects on which he worked with accomplished professional dancers. In Pelican (1963), he and Alex Hay are on roller skates with parachute-like constructions attached to their backs, and their interactions with Carolyn Brown, one of Merce Cunningham’s great dancers, have a comic-lyric impact. Some stills from Spring Training (1965), in which Paxton and Rauschenberg take turns holding each other horizontally at waist height, suggest a neatly carpentered erotic geometry. Rauschenberg can be an engaging theatrical presence, with his all-American boy-next-door good looks turned to poker-faced bohemian ends. “I don’t mess around with my subconscious,” he once said. That refusal to delve into his motives goes a long way toward accounting for what I can only describe as the soullessness of his paintings and sculptures. But when he performs, the soullessness strikes a chord—at least so it seems from the brief glimpses of those performances preserved in photographs and films.

Rauschenberg’s collaborations with choreographers, especially Merce Cunningham, have been the subject of a number of exhibitions. These include “Dancing Around the Bride: Cage, Cunningham, Johns, Rauschenberg and Duchamp,” which originated at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2012, and “Merce Cunningham: Common Time,” which is currently at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. A revival of the delicately pastoral “Summerspace,” with choreography by Cunningham, music by Morton Feldman, and dappled costumes and sets by Rauschenberg that suggest Monet’s waterlilies, was presented by Paul Taylor American Modern Dance in New York this season. The only time in the Rauschenberg retrospective when I felt entirely captivated was as I watched a clip from Travelogue, a 1977 collaboration with Cunningham and John Cage. Rauschenberg’s costumes and sets, with fabrics in dazzlingly saturated Silk Road hues, were the overheated setting for a solo performed with inward-turning intensity by (I believe) the dancer Chris Komar.

Writing of Rauschenberg in the 1990s, Leo Steinberg observed that “one ideal human condition is companionship, conviviality.” That is, I think, the value you feel in Rauschenberg’s work in Pelican, Spring Training, and Travelogue. But there are other collaborative works that have an unpleasantly industrialized feeling, as Steinberg himself acknowledged. Rauschenberg’s involvement with the engineer Billy Klüver and others on E.A.T.—an organization begun in 1966 to advance “Experiments in Art and Technology”—led straight to the Dadaism-by-committee that dominates so much of his later output.

Museumgoers who are dismayed by recent attacks on globalism and multiculturalism both at home and abroad may feel sympathetic to the international outreach campaign that Rauschenberg named ROCI (“Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange”). But I wonder if anybody can summon up much real enthusiasm for the glibly decorative posters in the retrospective that were generated by what amounted to an international goodwill tour that took Rauschenberg to Cuba, China, Russia, Germany, Mexico, and other countries between the mid-1980s and the early 1990s. According to Hiroko Ikegami in a catalog essay, the reactions to ROCI were mixed, with some hailing Rauschenberg as a force for artistic freedom while others saw him as colluding, at times perhaps inadvertently, with authoritarian leaders.

The Rauschenberg most people seem to prefer is funky, low-tech, a guy messing around. What I find unseemly is the scale on which Rauschenberg insisted on presenting his assorted quips and gambits. Making something out of cardboard boxes may be charming, but Rauschenberg tries my patience when he monumentalizes his charm offensive. Does anybody really need a nearly eight-foot-wide construction made of Nabisco Shredded Wheat boxes? Many have argued that the Combines, especially Monogram with its taxidermied goat and tire, are funny, but the humor, if that’s what it is, strikes me as contrived. Rauschenberg overinflates his whims and vagaries. While it cannot be denied that chance, randomness, impulse, and intuition are aspects of the artistic process, it’s easy to overemphasize their place in the genesis of a work of art. What counts is the decision to take the chance—and what one makes of it afterward. At the critical moment, when the artist must take control of what’s out of control, Rauschenberg is missing in action.

For all the swagger and cocksureness of Rauschenberg’s work, there’s something equivocal and unsettled about the cumulative effect of this retrospective. The more I looked, the more I felt that Rauschenberg had some lingering doubts about his own scattershot approach. Behind his nihilistic gesture of erasing a drawing by de Kooning—which he had been given by de Kooning expressly for that purpose—there was surely some recognition of the power of de Kooning’s agile, calligraphic line. Clearly, Rauschenberg felt the pull of creative spirits who were masters of their craft. He and Cy Twombly were lovers not long before Twombly produced his very finest early canvases, with their filigreed graffiti. And Rauschenberg was close to Merce Cunningham, one of the most refined dancers of the twentieth century, and close to some of the dancers whom Cunningham helped to shape.

In Rauschenberg’s works devoted to Dante’s Inferno and in some of his more loosely brushed canvases, you can see him paying obeisance to a painterly zest or verve that he finally lacked the discipline or technique to bring off. In certain of the paintings from his later years, the arrangements of quotidian photographic images suggest a yearning for poetic loveliness. Although these compositions don’t amount to much more than a sentimental old avant-gardist’s Hallmark greeting cards, there’s an easy, breezy feeling about a work like Triathlon (2005), with its snapshots of a motel, a fruit and vegetable stand, a bright yellow truck, and a hand holding a ball (seen in triplicate). However slapdash Rauschenberg’s work became, he remained alive to art’s seductions and rarely if ever succumbed to the hard sell that characterized the art stars who came to prominence a few years after him, especially Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol.

Steve Paxton has recalled Rauschenberg announcing, “I tend to see everything.” Rauschenberg also said, “I always wanted my work—whatever happened in the studio—to look more like what was going on outside the window.” These comments may be more revealing than he meant them to be. There’s a volubility about Rauschenberg’s visual imagination that is irreconcilable with the discipline art demands. However monumental or panoramic a work of art may be, there must always be some acknowledgment of the limits of the artist’s vision. Rauschenberg didn’t know the meaning of the word “limits.” There was something of the outrageousness of a Ponzi scheme in the way he took this or that avant-garde idea and inflated it—over and over again.

Rauschenberg’s Ponzi scheme hasn’t collapsed yet. Nearly a decade after his death, his critical fortunes are very much on the rise. Leah Dickerman concludes the MoMA catalog by observing that “his work serves as a prehistory for our own moment in time, the contemporary in its emergent form.” How long can artists hole up in that nowheresville between art and life? By now all bets are off.