About forty minutes into Risk, Laura Poitras’s messy documentary portrait of Julian Assange, the filmmaker addresses the viewer from off-camera. “This is not the film I thought I was making,” she says. “I thought I could ignore the contradictions. I thought they were not part of the story. I was so wrong. They are becoming the story.”

By the time she makes this confession, Poitras has been filming Assange, on and off, for six years. He has gone from a bit player on the international stage to one of its dramatic leads. His gleeful interference in the 2016 American presidential election—first with the release of e-mails poached from the Democratic National Committee, timed to coincide with, undermine, and possibly derail Hillary Clinton’s nomination at the Democratic Convention, and then with the publication of the private e-mail correspondence of Clinton’s adviser John Podesta, which was leaked, drip by drip, in the days leading up to the election to maximize the damage it might inflict on Clinton—elevated Assange’s profile and his influence.

And then this spring, it emerged that Nigel Farage, the Trump adviser and former head of the nationalist and anti-immigrant UK Independence Party (UKIP) who is now a person of interest in the FBI investigation of the Trump campaign’s ties to Russia, was meeting with Assange. To those who once saw him as a crusader for truth and accountability, Assange suddenly looked more like a Svengali and a willing tool of Vladimir Putin, and certainly a man with no particular affection for liberal democracy. Yet those tendencies were present all along.

In 2010, when Poitras began work on her film, Assange’s four-year-old website, WikiLeaks, had just become the conduit for hundreds of thousands of classified American documents revealing how we prosecuted the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, including a graphic video of American soldiers in an Apache helicopter mowing down a group of unarmed Iraqis, as well as for some 250,000 State Department diplomatic cables. All had been uploaded to the WikiLeaks site by an army private named Bradley—now Chelsea—Manning.

The genius of the WikiLeaks platform was that documents could be leaked anonymously, with all identifiers removed; WikiLeaks itself didn’t know who its sources were unless leakers chose to reveal themselves. This would prevent anyone at WikiLeaks from inadvertently, or under pressure, disclosing a source’s identity. Assange’s goal was to hold power—state power, corporate power, and powerful individuals—accountable by offering a secure and easy way to expose their secrets. He called this “radical transparency.” Manning’s bad luck was to tell a friend about the hack, and the friend then went to the FBI. For a long time, though, Assange pretended not to know who provided the documents, even when there was evidence that he and Manning had been e-mailing before the leaks.

Though the contradictions were not immediately obvious to Poitras as she trained her lens on Assange, they were becoming so to others in his orbit. WikiLeaks’s young spokesperson in those early days, James Ball, has recounted how Assange tried to force him to sign a nondisclosure statement that would result in a £12 million penalty if it were breached. “[I was] woken very early by Assange, sitting on my bed, prodding me in the face with a stuffed giraffe, immediately once again pressuring me to sign,” Ball wrote. Assange continued to pester him like this for two hours. Assange’s “impulse towards free speech,” according to Andrew O’Hagan, the erstwhile ghostwriter of Assange’s failed autobiography, “is only permissible if it adheres to his message. His pursuit of governments and corporations was a ghostly reverse of his own fears for himself. That was the big secret with him: he wanted to cover up everything about himself except his fame.”

Meanwhile, some of the company he was keeping while Poitras was filming also might have given her pause. His association with Farage had already begun in 2011 when Farage was head of UKIP. Assange’s own WikiLeaks Party of Australia was aligned with the white nationalist Australia First Party, itself headed by an avowed neo-Nazi, until political pressure forced it to claim that association to be an “administrative error.”

Most egregious, perhaps, was Assange’s collaboration with Israel Shamir, an unapologetic anti-Semite and Putin ally to whom Assange handed over all State Department diplomatic cables from the Manning leak relating to Belarus (as well as to Russia, Eastern Europe, and Israel). Shamir then shared these documents with members of the regime of Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko, who appeared to use them to imprison and torture members of the opposition. This prompted the human rights group Index on Censorship to ask WikiLeaks to explain its relationship to Shamir, and to look into reports that Shamir’s “access to the WikiLeaks’ US diplomatic cables [aided in] the prosecution of civil society activists within Belarus.” WikiLeaks called these claims rumors and responded that it would not be investigating them. “Most people with principled stances don’t survive for long,” Assange tells Poitras at the beginning of the film. It’s not clear if he’s talking about himself or others.

Advertisement

Then there is the matter of redaction. After the Manning cache came in, WikiLeaks partnered with a number of “legacy” newspapers, including The New York Times and The Guardian, to bring the material out into the world. While initially going along with those publications’ policies of removing identifying information that could put innocent people in harm’s way and excluding material that could not be verified, Assange soon balked. According to the Guardian journalists David Leigh and Luke Harding in WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy, their 2011 postmortem of their contentious collaboration with Assange on the so-called Afghan war logs—the portion of the Manning leaks concerning the conflict in Afghanistan—the WikiLeaks founder was unmoved by entreaties to scrub the files of anything that could point to Afghan villagers who might have had any contact with American troops. He considered such editorial intervention to “contaminate the evidence.”

“Well they’re informants. So, if they get killed, they’ve got it coming to them. They deserve it,” Leigh and Harding report Assange saying to a group of international journalists. And while Assange has denied making these comments, WikiLeaks released troves of material in which the names of Afghan civilians had not been redacted, an action that led Amnesty International, the Open Society Institute, the Campaign for Innocent Victims in Conflict, and the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission to issue a joint rebuke. The group Reporters Without Borders also criticized WikiLeaks for its “incredible irresponsibility” in not removing the names. This was in 2010, not long after Poitras approached Assange about making a film.

Lack of redaction—or of any real effort to separate disclosures of public importance from those that might simply put private citizens at risk—continued to be a flashpoint for WikiLeaks, its supporters, and its critics. In July 2016, presumably when Poitras was still working on Risk, WikiLeaks dumped nearly 300,000 e-mails it claimed were from Turkey’s ruling AKP party. Those files, it turned out, were not from AKP heavyweights but, rather, from ordinary people writing to the party, often with their personal information included.

Worse, WikiLeaks also posted links to a set of huge voter databases, including one with the names, addresses, and other contact information for nearly every woman in Turkey. It also apparently published the files of psychiatric patients, gay men, and rape victims in Saudi Arabia. Soon after that, WikiLeaks began leaking bundles of hacked Democratic National Committee e-mails, also full of personal information, including cell phone and credit card numbers, leading Wired magazine to declare that “WikiLeaks Has Officially Lost the Moral High Ground.”

Poitras doesn’t say, but perhaps this is when she, too, began to take account of the contradictions that eventually turned her film away from hagiography toward something more nuanced. Though she intermittently interjects herself into the film—to relate a dream she’s had about Assange; to say that he is brave; to say that she thinks he doesn’t like her; to say that she doesn’t trust him—this is primarily a film of scenes, episodic and nearly picaresque save for the unappealing vanity of its hero. (There is very little in the film about the work of WikiLeaks itself.)

Here is Julian, holed up in a supporter’s estate in the English countryside while under house arrest, getting his hair cut by a gaggle of supporters while watching a video of Japanese women in bikinis dancing. Here is Julian in a car with that other famous leaker, Daniel Ellsberg. Here is Julian instructing Sarah Harrison, his WikiLeaks colleague, to call Secretary Clinton at the State Department and tell her she needs to talk to Julian Assange. Here is Julian walking in the woods with one of his lawyers, certain that a bird in a nearby tree is actually a man with a camera. Here is Julian being interviewed, for no apparent reason, by the singer Lady Gaga:

Lady Gaga: What’s your favorite food?

Assange: Let’s not pretend I’m a normal person. I am obsessed with political struggle. I’m not a normal person.

Lady Gaga: Tell me how you feel?

Assange: Why does it matter how I feel? Who gives a damn? I don’t care how I feel.

Lady Gaga: Do you ever feel like just fucking crying?

Assange: No.

And here is Julian, in conversation with Harrison, who is also his girlfriend:

Advertisement

Assange: My profile didn’t take off till the sex case. [It was] very high in media circles and intelligence circles, but it didn’t really take off, as if I was a globally recognized household name, it wasn’t till the sex case. So I was joking to one of our people, sex scandal every six months.

Harrison: That was me you were joking to. And I died a little bit inside.

Assange: Come on. It’s a platform.

The sex case to which Assange is referring is the one that began in the summer of 2010 on a trip to Sweden. While there, Assange had sex with two young supporters a few days apart, both of whom said that what started out as consensual ended up as assault. Eventually, after numerous back-and-forths, the Swedish court issued an international arrest warrant for Assange, who was living in England, to compel him to return to Sweden for questioning. Assange refused, declaring that this was a “honey pot” trap orchestrated by the CIA to extradite him to the United States for publishing the Manning leaks.

After a short stay in a British jail, subsequent house arrest, and many appeals, Assange was ordered by the UK Supreme Court, in May 2012, to be returned to Sweden to answer the rape and assault charges. Assange, however, claiming that there was a secret warrant for his arrest in the United States (though the extradition treaty between Sweden and the US prohibits extradition for a political offense), had made other arrangements: he had applied for, and was granted, political asylum in Ecuador. Because the British government refused “safe passage” there, Assange took refuge in the Ecuadorian embassy in London.

Poitras was with Assange in an undisclosed location in London as the British high court in Parliament Square was issuing its final ruling. The camera was rolling and no one was speaking—it was all sealed lips and pantomime—as Assange dyed his hair red and dressed in biker’s leather in order to make a mad dash on a motorcycle across town to the embassy. (There’s a sorrowful moment when his mother, who, inexplicably, is in the room, too, writes “I love you, honey,” on a piece of notebook paper and hands it and a pen to her son and he waves her off.)

This past January, five years into Assange’s self-imposed exile, he promised to finally leave the embassy and turn himself over to the Americans if President Obama were to grant clemency to Chelsea Manning, who had been sentenced to thirty-five years in prison for giving documents to WikiLeaks. Obama did; Assange didn’t. In May, the same month Manning left prison, Sweden dropped all charges against Assange. He remains in the embassy.

The “sex case,” as Assange called it, figures prominently in Risk. It serves to reveal his casual and sometimes noxious misogyny, and it is a foil for him to conflate the personal with the political, using the political to get out of answering to the personal, and the personal to claim that he’s the victim here. “Who is after you, Mr. Assange?” Lady Gaga asks. “Formally there are more than twelve United States intelligence organizations,” Assange tells her, reeling off a list of acronyms. “So basically a whole fucking bunch of people in America,” she says, and then he mentions that the Australians, the British, and the Swedes are also pursuing him.

Whether this is true or not has long been a matter of dispute. The Swedes definitely wanted him to return to their country, and the British were eager for him to abide by the Swedish warrant, and he made no friends in the Obama administration. Following the Manning leaks in 2010, the attorney general, Eric Holder, made it clear that the Department of Justice, along with the Department of Defense, was investigating whether Assange could be charged under the 1917 Espionage Act, though no warrant was ever issued publicly. Hillary Clinton, then the secretary of state, said that WikiLeaks’s release of the diplomatic cables was “an attack on the international community [and] we are taking aggressive steps to hold responsible those who stole this information.” Still, Assange’s self-exile in the embassy, which the United Nations condemned as an “arbitrary detention,” was predicated on his belief that the Americans were lying in wait, ready at any moment to haul him to the US, where his actions might land him in prison for a very long time, or even lead to his execution.

All this was well before Assange was accused of using WikiLeaks as a front for Russian agents working to undermine American democracy during the 2016 presidential election. And it was before candidate Trump declared his love for the website and then watched as Assange released a huge arsenal of CIA hacking tools into the public domain less than two months into Trump’s presidency. This, in turn, prompted the new CIA director, Mike Pompeo, who appeared to have no problem with WikiLeaks when it was sharing information detrimental to the Democrats, to declare WikiLeaks a “hostile intelligence service,” and the new attorney general, Jeff Sessions, to prepare a warrant for Assange’s arrest. If the Justice Department wasn’t going after Assange before, it appears to be ready to do so now.

Despite Assange’s vocal disdain for his former collaborators at The New York Times and The Guardian, his association with those journalists and their newspapers is probably what so far has kept him from being indicted and prosecuted in the United States. As Glenn Greenwald told the journalist Amy Goodman recently, Eric Holder’s Justice Department could not come up with a rationale to prosecute WikiLeaks that would not also implicate the news organizations with which it had worked; to do so, Greenwald said, would have been “too much of a threat to press freedom, even for the Obama administration.” The same cannot be said with confidence about the Trump White House, which perceives the Times, and national news organizations more generally, as adversaries. Yet if the Sessions Justice Department goes after Assange, it likely will be on the grounds that WikiLeaks is not “real” journalism.

This charge has dogged WikiLeaks from the start. For one thing, it doesn’t employ reporters or have subscribers. For another, it publishes irregularly and, because it does not actively chase secrets but aggregates those that others supply, often has long gaps when it publishes nothing at all. Perhaps most confusing to some observers, WikiLeaks’s rudimentary website doesn’t look anything like a New York Times or a Washington Post, even in those papers’ more recent digital incarnations.

Nonetheless, there is no doubt that WikiLeaks publishes the information it receives much like those traditional news outlets. When it burst on the scene in 2010, it was embraced as a new kind of journalism, one capable not only of speaking truth to power, but of outsmarting power and its institutional gatekeepers. And the fact is, there is no consensus on what constitutes “real” journalism. As Adam Penenberg points out, “The best we have comes from laws and proposed legislation which protect reporters from being forced to divulge confidential sources in court. In crafting those shield laws, legislators have had to grapple with the nebulousness of the profession.”

The danger of carving off WikiLeaks from the rest of journalism, as the attorney general may attempt to do, is that ultimately it leaves all publications vulnerable to prosecution. Once an exception is made, a rule will be too, and the rule in this case will be that the government can determine what constitutes real journalism and what does not, and which publications, films, writers, editors, and filmmakers are protected under the First Amendment, and which are not.

This is where censorship begins. No matter what one thinks of Julian Assange personally, or of WikiLeaks’s reckless publication practices, like it or not, they have become the litmus test of our commitment to free speech. If the government successfully prosecutes WikiLeaks for publishing classified information, why not, then, “the failed New York Times,” as the president likes to call it, or any news organization or journalist? It’s a slippery slope leading to a sheer cliff. That is the real risk being presented here, though Poitras doesn’t directly address it.

Near the end of Risk, after Poitras has shown Assange a rough cut of the film, he tells her that he views it as “a severe threat to my freedom and I must act accordingly.” He doesn’t say what he will do, but when the film was released this spring, Poitras was loudly criticized by Assange’s supporters for changing it from the hero’s journey she debuted last year at Cannes to something more critical, complicated, and at best ambivalent about the man. Yet ambivalence is the most honest thing about the film. It is the emotion Assange often stirs up in those who support the WikiLeaks mission but are disturbed by its chief missionary.

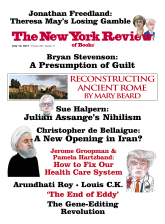

This ambivalence, too, is what makes Risk such a different film from Citizen Four (2014), Poitras’s intense, resolute, Oscar-winning documentary about Edward Snowden. While Snowden and Assange are often twinned in the press and in the public imagination, these films demonstrate how false that equivalence is. Snowden leaked classified NSA documents that he said showed rampant unconstitutional intrusions by the government into the private lives of innocent citizens, doing so through a careful process of vetting and selective publication by a circle of hand-picked journalists. He identified himself as the leaker and said he wanted to provoke a public debate about government spying and the right of privacy. Assange, by contrast, appears to have no interest in anyone’s privacy but his own and his sources’. Private communications, personal information, intimate conversations are all fair game to him. He calls this nihilism “freedom,” and in so doing elevates it to a principle that gives him license to act without regard to consequences.

The mission Assange originally set out to accomplish, though—providing a safe way for whistleblowers to hold power accountable—has, in the past few years, eclipsed WikiLeaks itself. Almost every major newspaper, magazine, and website now has a way for leakers to upload secret information, most through an anonymous, online, open-source drop box called Secure Drop. Based on coding work done by the free speech advocate Aaron Swartz before his death and championed by the Freedom of the Press Foundation—on whose board both Laura Poitras and Edward Snowden sit, and which is a conduit for donations to WikiLeaks among other organizations—Secure Drop gives leakers the option of choosing where to upload their material. The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Yorker, Forbes, and The Intercept, to name just a few, all have a way for people to pass secrets along to journalists.

It is not yet known why a National Security Agency contractor named Reality Leigh Winner didn’t use a digital drop box when she leaked a classified NSA document to The Intercept in May outlining how Russian cyber spies hacked into American election software. Unlike Edward Snowden, who carefully covered his tracks before leaking his NSA cache to Glenn Greenwald (before Greenwald started The Intercept) and Laura Poitras (who filmed Snowden’s statement of purpose, in which he identified himself as the leaker), Winner used a printer at work to copy the document, which she then mailed to The Intercept. What she and those at The Intercept who dealt with the document did not know, apparently, is that this government printer, like many printers, embeds all documents with small dots that reveal the serial number of the machine and the time the document was printed. After The Intercept contacted the NSA to verify the document, the FBI needed only a few days to find Winner and arrest her.

We will soon get to witness what the Trump administration does to those who leak classified information, and to those who publish it. WikiLeaks, apparently, will be providing the government with an assist. It is offering a $10,000 reward for “the public exposure” of the reporter whose ignorance or carelessness led the FBI to Reality Winner’s door. Such are the vagaries of radical transparency.