More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

The Bull’s-Eye on Your Thoughts

Today digital privacy exists only at the discretion of the companies that mediate our online engagement. But what happens when those companies, an employer, school administrators, or the government have access to our neural data?

The Battle for Your Brain: Defending the Right to Think Freely in the Age of Neurotechnology

by Nita A. Farahany

Reading Our Minds: The Rise of Big Data Psychiatry

by Daniel Barron

November 2, 2023 issue

Private Eyes

The surveillance economy has all but eliminated Americans’ ability to be “let alone.”

The Fight for Privacy: Protecting Dignity, Identity, and Love in the Digital Age

by Danielle Keats Citron

Seek and Hide: The Tangled History of the Right to Privacy

by Amy Gajda

March 9, 2023 issue

The Specter of Our Virtual Future

The metaverse opens up a new and seemingly infinite opportunity to extract data and sell ads.

The Metaverse: And How It Will Revolutionize Everything

by Matthew Ball

October 20, 2022 issue

The Human Costs of AI

Artificial intelligence does not come to us as a deus ex machina but, rather, through a number of dehumanizing extractive practices, of which most of us are unaware.

Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence

by Kate Crawford

We, the Robots?: Regulating Artificial Intelligence and the Limits of the Law

by Simon Chesterman

Futureproof: 9 Rules for Humans in the Age of Automation

by Kevin Roose

The Myth of Artificial Intelligence: Why Computers Can’t Think the Way We Do

by Erik J. Larson

October 21, 2021 issue

Weaponizing the Web

Nicole Perlroth's investigation into the shadowy world of cyberweaponry predicts an unsettling future for global security.

This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends: The Cyberweapons Arms Race

by Nicole Perlroth

April 8, 2021 issue

The Drums of Cyberwar

All the critical infrastructure that undergirds much of our lives is at risk of being held hostage or decimated by hackers

Sandworm: A New Era of Cyberwar and the Hunt for the Kremlin’s Most Dangerous Hackers

by Andy Greenberg

December 19, 2019 issue

In Praise of Public Libraries

A public library stands in stark opposition to the materialism and individualism that otherwise define our culture.

Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life

by Eric Klinenberg

The Library Book

by Susan Orlean

Ex Libris

a film directed by Frederick Wiseman

April 18, 2019 issue

Apologize Later

The Cleaners

a PBS Independent Lens documentary film directed by Moritz Riesewieck and Hans Block

The Facebook Dilemma

a PBS Frontline documentary television series directed by James Jacoby

January 17, 2019 issue

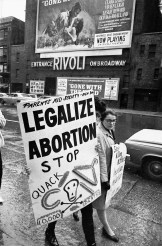

How Republicans Became Anti-Choice

These days, the litmus test for Republican politicians and judges is opposition to abortion. This was not always the case.

Reversing Roe

a documentary film directed and produced by Ricki Stern and Annie Sundberg

November 8, 2018 issue

The Known Known

The future of privacy in the era of “surveillance capitalism”

The Known Citizen: A History of Privacy in Modern America

by Sarah E. Igo

Habeas Data: Privacy vs. the Rise of Surveillance Tech

by Cyrus Farivar

Beyond Abortion: Roe v. Wade and the Battle for Privacy

by Mary Ziegler

Privacy’s Blueprint: The Battle to Control the Design of New Technologies

by Woodrow Hartzog

September 27, 2018 issue

Bitcoin Mania

‘Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology Behind Bitcoin Is Changing Money, Business, and the World’ by Don Tapscott and Alex Tapscott

Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology Behind Bitcoin Is Changing Money, Business, and the World

by Don Tapscott and Alex Tapscott

Attack of the Fifty Foot Blockchain: Bitcoin, Blockchain, Ethereum and Smart Contracts

by David Gerard

January 18, 2018 issue

Subscribe and save 50%!

Read the latest issue as soon as it’s available, and browse our rich archives. You'll have immediate subscriber-only access to over 1,200 issues and 25,000 articles published since 1963.

Subscribe now

Subscribe and save 50%!

Get immediate access to the current issue and over 25,000 articles from the archives, plus the NYR App.

Already a subscriber? Sign in