Almost ten months into the Trump administration, how are the Democrats doing as an opposition party? The first instinct of rank-and-file liberals is always to dismiss them as ineffective (just as, not coincidentally, it is the first instinct of conservatives to bemoan Republicans’ congenital lack of spine). And the first instinct of the mainstream press is to feed that narrative with a steady supply of “Democrats in disarray” articles. It’s an old storyline and a mossy one; my friends and I, in e-mails, mockingly use the hashtag #demsindisarray when we note articles that overhype some new Democratic calamity.

Yet there is some truth to both claims. “Disarray” isn’t exactly an unfair adjective for a party that controls no branch of the federal government and only sixteen governors’ mansions and thirteen state legislatures (Republicans control thirty-two, and five are divided). And, I might add, a party still not quite over the shock of that loss last November.

As for effectiveness, in the country’s recent history, the Democrats have never been as united or effective in opposition as the Republicans. This is less a matter of will and backbone than of the Democrats’ loyal voter base, both smaller and less rabidly monolithic than the Republicans’. To take the highest-profile example of the failure of Democratic opposition in recent times, 43 percent of Democrats in both houses of Congress (110 out of 257) voted for the Iraq war resolution of 2002. One can certainly see that as lack of backbone. At the same time, pre-war polls showed that Democratic survey respondents said they supported the war at levels around 40 percent.1 So, like it or not, those congressional Democrats reflected the will of the Democratic rank-and-file pretty closely.

The Republican Party of the past quarter-century, in contrast, would never give a Democratic president 43 percent of its vote on anything of importance. That’s not because it’s tougher or meaner, but because it’s responding to a different and less forgiving political reality—one in which, over the past thirty years, lavishly financed conservative pressure groups and right-wing media outlets have combined to create a base that brooks no compromise or accommodation. For a Daily Beast column back in 2011, I compared opposition-party levels of support in Congress for George W. Bush and Barack Obama on four of each president’s major initiatives.2 The average Democratic support for Bush in both houses on those four bills was 41.1 percent. The average Republican support for Obama on his four bills was 5.75 percent. The two parties are just different species.

However, in the age of Donald Trump, they’re becoming less different. True, Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi, the Democrats’ leaders, did make a deal with the president to delay a vote on the debt ceiling for three months, a deal virtually shoved in their faces by Trump at an early September White House parley that the president described to the press as “a very good meeting with Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer” (GOP leaders Mitch McConnell and Paul Ryan had been in the room, too). That measure, attached to Hurricane Harvey relief, sailed through Congress. The next week Schumer announced that the trio had also reached a deal to protect the so-called Dreamers, people who were brought to the United States as undocumented children. There has been no congressional action on that yet, but in early October the White House announced that it would attach to any Dreamers legislation some harder-line measures like funding for a border wall and 10,000 more immigration agents. Schumer and Pelosi quickly signaled that any deal along those lines was impossible.

On other matters, when it comes to big legislation, congressional Democrats have been consistent in their opposition to the White House. They forced McConnell to invoke the “nuclear option” on Supreme Court Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch’s nomination when it failed to get the sixty votes needed to clear the procedural “cloture” hurdle. Democratic senators have blocked judicial nominees twice by refusing to return to the chairman of the Judiciary Committee a “blue slip” signaling approval of the nominee. This was a practice Republicans used aggressively during the Obama years, though McConnell is now threatening to abolish it.

A unanimous stand has been taken by Senate Democrats on three health care votes. Of course, the Democrats didn’t block health care repeal—the Republicans did that themselves. But it was impressive that not a single Democrat in either house voted for it, especially in the Senate, where nine Democratic senators will be defending their seats next year in states Trump won.

The Democrats are showing more resolve partly because of the extreme nature of this presidency, but mostly because their base is getting a bit—a bit—more like the Republican base. This may be quite a bad thing for the country in the long term, but in the short term it’s very much a good thing. The liberal base is larger and more energized than it’s been for many years. The Indivisible movement, which started after the election when four former congressional staffers wrote a pamphlet that caught fire called Indivisible: A Practical Guide for Resisting the Trump Agenda, was an immediate success and now boasts nearly six thousand chapters across the country—most in the places you’d expect, but eleven in Idaho, seven in Wyoming, and two in my purple-leaning-red hometown of Morgantown, West Virginia. When Republican members of Congress were strafed at town hall meetings last summer by constituents irate over health care, chances are that one of the local Indivisible chapters helped organize those attacks.

Advertisement

The women’s marches held across the country and the world on January 21 have likewise spurred a sustained engagement on the part of thousands. A Women’s Convention will be held in late October in Detroit, according to its website, “for a weekend of workshops, strategy sessions, inspiring forums, and intersectional movement building to continue the preparation going into the 2018 midterm elections.” Speaking of those midterms, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee reports that candidate recruitment is far ahead of where it was in 2016. A staffer at the DCCC told me that it has identified eighty House seats as worth contesting and already has good candidates for seventy of them. The main reason? “A lot of people are finally saying yes,” the staffer said; they see the act of running for office as more of a duty post-Trump, after previous demurrals. Around ten military veterans are running as Democrats, and there’s a group of people motivated by the health care repeal efforts—doctors and people with personal health scares and stories to tell.

All this activity has made Democrats in Congress begin to do something they haven’t done for many years: respond to pressure from the left. Ever since Ronald Reagan’s defeat of Walter Mondale in 1984 and the rise of the Democratic Leadership Council the next year, Washington Democrats have feared being seen as too liberal. Now, they’re more likely to fear being seen as not liberal enough. This creates no friction when it comes to deciding what they’re against. On the Republican health care bills, there wasn’t much space between Senators Bernie Sanders and Joe Manchin; both voted no all three times, and there was never any sense that Manchin (whose state, West Virginia, Trump carried by more than forty points) was wavering. West Virginia accepted the Medicaid expansion, which covered about 175,000 residents in that state of very poor health indexes.

The tax bill now working its way through Congress will be a pivotal test of both the Democrats and the resistance and may tell us a lot about the extent to which our politics have really changed. Two arguments have long been used to sell tax cuts, arguments the Democrats have never really won since Ronald Reagan’s time. First, Republicans have always downplayed the enormous benefits going to the wealthy and emphasized the comparatively minuscule savings for the middle class. Consequently, a significant minority (though not a majority) of Democratic lawmakers has always voted for Republican tax cuts. The cuts were popular, and these Democrats felt pressured to support them. Second, Reagan promised that enormous tax cuts would lead to economic growth, and when, following the 1986 Tax Reform Act, the gross domestic product grew at rates above 3.5 percent and the unemployment rate slipped down to near 5 percent, he looked like he was delivering on that promise, so Republicans were able to say, “See? Supply-side economics works.”

That 1986 law was the last major overhaul of the tax code. Thirty years later, what’s changed? On the second point, I think quite a lot. George Bush’s two large tax cuts of 2001 and 2003 did not spur great growth, so Republicans should not be able to make the “supply-side works” argument effectively this time. They’re certainly making it; I’m writing these words a few days after the proposal was introduced, and on my television I hear little else. But I also hear Democrats and liberal commentators firing back with the Bush example. That is an argument the Democrats should be able to win.

On the first point, though, we don’t yet know if the country has changed since 1986. Is a majority of the American middle class willing to give corporations and the rich enormous tax breaks as long as they get a little slice of the pie too? I keep a close watch on the polling on this. In general, majorities are deeply skeptical of large tax cuts for corporations and the rich. There is a broad sense that large businesses (as opposed to small businesses, for which people support relief) don’t pay their share.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, people don’t seem to be consumed with the thought that they’re paying too much in taxes. The last time Gallup, for example, asked this question, in April of this year, 51 percent said their taxes were “too high,” but 42 percent said they were “about right.”3 If Democrats and the energized resistance can persuade middle-income people that the few dollars they stand to net aren’t worth yet another enormous giveaway to the very rich—who will save tens of thousands if the top rate is reduced from 39.6 percent to 35 percent—then an important milestone will have been reached.

All the above is about opposing. As noted, there’s not a whole lot of disagreement among Democrats about what they’re against. What they should be for is another matter. It’s probably a problem that they can put off for a little while. Midterm elections are always referenda on the incumbent president, so until then, Democrats mostly need to keep their base agitated enough about Trump and the Republicans to go vote. Once that bar is cleared, talk will turn to 2020, and presidential candidates, and proposals and ideas.

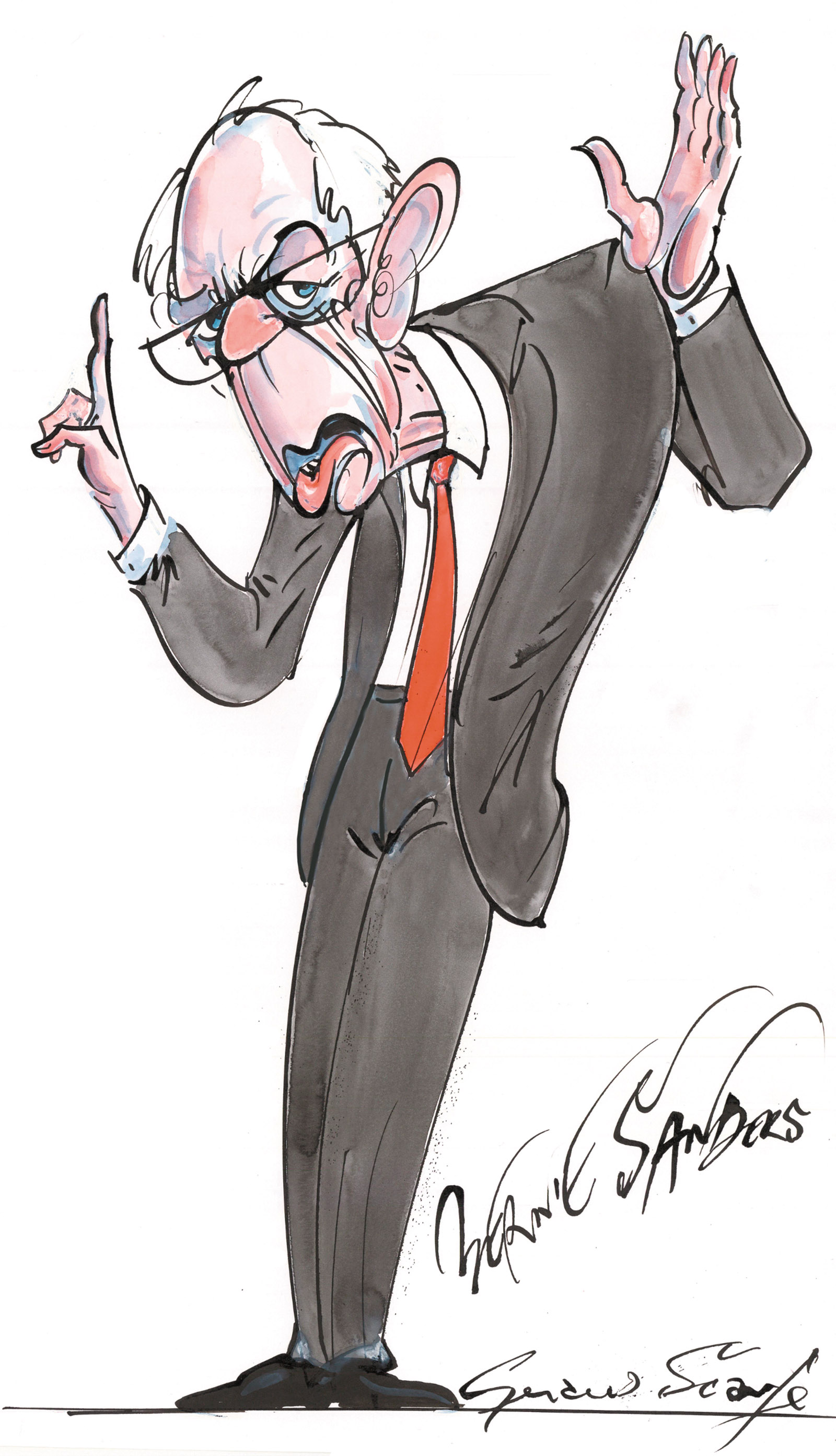

The big questions are how far left the party will go, and whether the broader American public will follow it. In his new book, Bernie Sanders Guide to Political Revolution, the man who is still, at seventy-six years of age, the junior senator from Vermont (to Patrick Leahy) writes that “on major issue after major issue, the vast majority of Americans support a progressive agenda and widely reject the economic views of the Republican Party.”4 This is certainly true on paper. Poll after poll shows majority (though perhaps not “vast”) support for a higher minimum wage and paid medical leave and more paid vacation time and more reliable scheduling at the workplace and the rest. Polls have generally even shown support for breaking up the big banks, an idea regarded in official Washington as so radical as to be unserious.

Sanders’s Guide is not really a book so much as a campaign pamphlet wedged between hard covers: a compendium of his speeches and tweets with stars and bullet points and pull quotes, photos of the great man striking purposeful poses, and stark illustrations by Jude Buffum. Sanders’s argument here and elsewhere is that if the Democrats cultivate a hard line on these and other matters and stick to it, they will conjure into existence the majority constituency that will enable them to pass this ambitious agenda. “We must move boldly forward to revitalize American democracy and bring millions of young people and working people into an unstoppable political movement that represents all of us, not just the billionaire class,” he writes.

This assertion shouldn’t be dismissed. Polling suggests that nonvoters are heavily Democratic. A Pew survey of nonvoters in 2012 found that 52 percent either identify as Democrats or lean Democratic, while the corresponding number on the Republican side was 27 percent.5 So it’s possible that there’s a dormant constituency out there waiting to be inspired. In addition, engaging previously apathetic citizens creates the kind of momentum and excitement that Sanders built in 2015–2016.

But many Democratic politicians who’ve lived through the last thirty years in this country are skeptical about all this. Some, who came of age in a mostly conservative era and represent states other than very liberal Vermont, don’t believe in their bones that the American public is ready to embrace a Sandersesque agenda. Others surely worry about how some of this sounds to donors, both in New York and out in Silicon Valley, where they’re fine with personal freedom but not so keen on government regulation of the sort Sanders espouses. Still others don’t like the race Sanders ran against Hillary Clinton and believe he developed some attack lines—about her coziness with corporations, say—that Trump picked up and that helped push voters on the left away from her in crucial states. Finally, some point out that while Sanders did energize young people, he performed rather poorly among African-Americans, Latinos, and single women—the three blocs that are the Democrats’ most reliable voters.

Yet there is little doubt that right now, Sanders is driving the action in this party he refuses to join. Schumer and Pelosi lead the opposition to Trump, but Sanders is shaping the future direction of the Democrats. His decision to introduce a “Medicare-for-all” bill in September was both a way to keep him in the spotlight and to force the party’s 2020 presidential aspirants to show their cards. Four possible candidates cosponsored the bill: Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, Kirsten Gillibrand of New York, Cory Booker of New Jersey, and Kamala Harris of California. Minnesota’s Amy Klobuchar, whose name usually appears on 2020 lists, did not join the bill. Nor did Sherrod Brown of Ohio, whose name sometimes appears on such lists. Sanders’s own name, of course, appears on and sometimes tops such lists, although some wonder if he’ll be too old or if he can bottle that lightning a second time.

I would like to have been a fly on the wall as each of these senators discussed with aides whether to cosponsor the bill. Warren must face the voters in 2018, but she has drawn no first-tier declared competition so far, and in Massachusetts, association with Sanders and single-payer carries little risk. Gillibrand is in a nearly identical situation—she’s up for reelection next year, has no serious competition yet, and in New York single-payer also is a nonissue (Governor Andrew Cuomo, by the way, another likely entrant, recently announced his conversion to single-payer). Booker is not up for reelection in 2018, but he is regarded suspiciously by the left, which sees him as too close to Wall Street, so he needs to establish his credentials. Harris, a new senator who also won’t be facing voters in 2018, spent the summer getting attacked on Twitter by “Bernie bros” for being a corporatist hack in the Clinton mold (about one quarter fairly). She signed on surely in response to those criticisms, at least in part.

Klobuchar’s decision not to join the bill is interesting. She does face her state’s voters next year. The only declared Republican challenger is a state legislator, Jim Newberger, the kind of candidate who will have a hard time raising Senate-level money unless he has a breakthrough moment that shows donors he’s a decent bet. But Trump came close to beating Clinton last year in Minnesota, against all expectations; the margin was just 1.4 percent. So that’s a state, unlike Massachusetts or New York, where being at Bernie’s side might be a liability. The same is true for Sherrod Brown, who is locked in a very tough reelection fight in a state Trump carried by eight points.

For most of these senators, signing on to Sanders’s bill is risk-free—for now. But someday, the Congressional Budget Office will score the bill, and it will estimate the taxes needed to pay for it. They will almost surely be quite large. The only state that has tried to implement single-payer is Sanders’s own Vermont, where, in late 2014, the then governor, Peter Shumlin, a Democrat and longtime single-payer advocate, shelved it after releasing a financial report showing that single-payer would instantly double the state’s budget and lead to large tax increases for individuals and businesses.

Sanders has responded to this problem in the past by saying that the program would be easier to implement at the federal level and that most people would actually pay less in increased taxes than they now pay in deductibles and copayments, which he would eliminate entirely. That may be a debate worth having in 2019 and 2020. But there’s probably a reason why Sanders decided not to put specific revenue estimates in his bill, just general suggestions about how revenue might be raised.

That’s the inside baseball. But here, if I may put it this way, is the outside baseball. I hear no one in the Democratic Party addressing the great crisis of our age: the crisis of Western liberalism that has brought us Brexit and Trump and Alternative für Deutschland and the likelihood of Senator Roy Moore of Alabama. What went wrong?

Every Democrat will talk about fighting harder, standing up to Trump, and supporting the policies that will win back just enough white working-class voters in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin. Those are the three states that were punches in the gut. I admit that I thought it virtually impossible that Clinton could lose them. They’d voted Democratic since 1992. They seemed settled, but they were not, and a combined 77,744 votes in all three states made the difference. So in one sense, that’s all the Democrats need to do in 2020—flip around 78,000 votes.

That’s to win. But to govern, to lead, to create a coalition of 52, 53 percent (they almost certainly can’t get a larger majority in this polarized age) that has a chance to force a fundamental change in direction, they have to do more. This will not be achieved through any list of policy positions. It’s quite true that Democrats, and not Republicans, support policies that will relieve the various immiserations of the Trump voters. But people don’t listen to that. And in any case, such policies today have become racialized. When a white working-class voter hears a Democrat talk about the minimum wage, he probably hears “handout.”

Some Democrat needs to be able to speak frankly about the postwar liberal order and the world—to defend its triumphs without apology, to note in a spirit of open self-critique where it has failed, and to lay out the corrections that need to be made. Heading into 2020, voters will be sizing up Democrats in the following way: Okay, you people lost to that buffoon. What do you have to say for yourselves? Have you figured it out?

It’s the candidate who can articulate answers to those questions, not the candidate who most insistently backs single-payer or demands a minimum wage two dollars higher than the others do, who has the potential to be the Roosevelt or Kennedy of our time. I get no sense that any Democrat is even thinking like this. Donald Trump, in his shallow and malevolent way, does think like this. The Democrats had better start.

—October 11, 2017

This Issue

November 9, 2017

Black Lives Matter

What Are We Doing Here?

Small-Town Noir

-

1

See, for example, Caroline Smith and James M. Lindsay, “Rally ’Round the Flag: Opinion in the United States Before and After the Iraq War,” the Brookings Institution, June 1, 2003. ↩

-

2

See my article “Data Show the GOP’s One-Sided War on Democrats,” The Daily Beast, September 9, 2011. The four Bush initiatives I examined were the first tax cut, the “No Child Left Behind” bill, the Iraq war vote, and the Medicare expansion of 2003. The four Obama initiatives were the stimulus, the Affordable Care Act, the Dodd-Frank financial bill, and the “don’t ask, don’t tell” repeal. I think it was fair and accurate to call these at the time each administration’s major legislative actions. ↩

-

3

See Gallup News, Taxes, at news .gallup.com/poll/1714/taxes.aspx. Gallup has been asking this question frequently (though not quite annually) since 1956. Remarkably, views haven’t changed all that much in sixty years, even though income taxes were substantially higher in the 1950s than today. This year’s nine-point differential is, however, eleven points less than last year’s 57–37 split. ↩

-

4

Henry Holt, 2017. ↩

-

5

See “Nonvoters: Who They Are, What They Think,” Pew Research Center, November 1, 2012. ↩