In 1868 the Dutch-born English painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema completed his Phidias and the Frieze of the Parthenon, Athens, in which he imagined a sort of varnishing day at the Acropolis. The good citizens of Athens, husbands and wives, have turned out for the occasion, climbed the somewhat rickety-looking wooden scaffolding, and are now admiring the work later known, in its ruined state, as the Elgin Marbles.

Phidias himself stands with a quiet pride in front of his roped-off frieze, which—this is the talking point of the painting—has been cheerfully colored in: the flesh parts of the figures in the reliefs are shown as a rich earthy red, their hair is black, the background a grayish blue. Cloaks and tunics and some of the horses are white, but the total effect is one of a bold polychromy—set off by ornamental borders richly gilded and a painted beamed ceiling that would not have looked out of place in Alma-Tadema’s own beautiful London home—or indeed in one of the “artistic houses” of New York, where stencils and ornament and rich colors enjoyed their vogue in the 1890s, and where a frieze for the parlor or any other grand room might be conjured up on the basis of the Parthenon marbles, the Bayeux Tapestry, or a collage of Japanese woodblock prints. It is not, however, the coloring of Phidias’s work that immediately strikes us as anachronistic. It is the vision of husbands and wives on seemingly equal terms attending a cultural event, rather as, in Alma-Tadema’s day, patrons and the public began making Sunday visits to artists’ studios in places like St. John’s Wood.

Nevertheless, the thickly colored Phidian frieze is a puzzle. If this is indeed what Greek polychromed marble looked like, one wonders what on earth was the point of seeking out the purest white marble from Paros, which, according to Pliny, was not so much quarried as mined by lamplight (a dreadful task, surely) to be transported across the sea in specially constructed ships. Why did the famous sculptors of the period ignore other colored or veined marbles (which might perhaps have taken paint just as well)? And why does Pliny, who was familiar with Greek statuary, much of which had been looted and brought to Rome, make no reference to its having been painted?

Among the first scholars to suggest that the Greeks had colored their statues was Quatremère de Quincy in 1814. He thought that the ancients “separated much less in their works than one imagines the pleasure of the eyes from that of the spirit; that is to say that richness, variety and beauty of materials…were for them more intimately linked than one thinks to intrinsic beauty.” Variety here stands in opposition to purity of color and form. Advocates of polychromy in sculpture brought the same gaudy enthusiasm to architecture. So, in a lecture delivered in December 1850, “On the Decorations Proposed for the Exhibition Building in Hyde Park,” Owen Jones, later famous as the compiler of The Grammar of Ornament, explained to his audience why he was about to decorate the interior of the Crystal Palace (due to open the next year) in strong primary colors:

We are only now beginning to shake off the trammels, which the last age of universal whitewashing has left us, when everything but pure white was considered universally (and indeed is still held by many) to be wanting in good taste. The evidences of colour on the monuments of Greece were first stoutly denied, and then, when proved to exist, they were supposed to be the work of barbarous after-ages; and even when this last position was no longer tenable, it was said that the ancients, though perfect masters of form, were ignorant of colour, or that they, at any rate, had misapplied it. Men were reluctant to give up their long-cherished idea of the white marble of the Parthenon, and of the simplicity of its forms, and they refused to regard it as a building, coloured in every part, and covered with a most elaborate system of ornamentation.

Jones was a gutsy lecturer, an expert on color in the ancient world (he had studied it firsthand in Greece, Egypt, and at the Alhambra in Spain), and a polemicist for his views. When the Crystal Palace was dismantled and reassembled in South London, he created a colorful Greek court in which brightly painted plaster casts of the Elgin Marbles were displayed. Later he created a kind of temple for the display of John Gibson’s Tinted Venus, a marble statue subtly and (to Victorian taste) disconcertingly colored. Seen now, in “Like Life,” the excellent show at the Met Breuer, the Gibson Venus seems inoffensive enough (it has apparently lost some of its coloration), but at the time it was deemed shockingly sensual. This Venus had lost her “chastity” and was something of a brazen hussy.

Advertisement

But Jones was still on the warpath, and his pavilion for the Tinted Venus bore inscriptions in Latin: NEC VITA NEC SANITAS NEC PVLCRITVDO NEC SINE COLORE JVVENTVS (Without color there is neither life, nor health, nor beauty, nor youth) and FORMAS RERVM OBSCVRAS ILLVSTRAT CONFVSAS DISTINGVIT OMNES ORNAT COLORVM DIVERSITAS SVAVIS (The sweet variety of colors enhances the dark form of things, differentiates what is confused, and ornaments everything). Putting it in Latin, in the manner of an inscription (all those V’s for U’s), was a good way of deflecting the moral outrage the Venus had provoked.

But it did not win the aesthetic argument—not in the Protestant North, at least. Sculpture, it was felt, should be in marble or bronze. If marble, then a pure white Carrara-style marble was the correct choice—correct because it was seen as the difficult choice by dint of its hardness. Théophile Gautier’s poem “L’Art” (1852), sometimes quoted as a plea for whiteness in sculpture, is more of an argument for taking the difficult route at all costs:

Statuaire, repousse

L’argile que pétrit

Le pouce

Quand flotte ailleurs l’esprit;

Lutte avec le carrare,

Avec le paros dur

Et rare,

Gardiens du contour pur.

(Sculptor, reject the clay that the thumb models while the mind is on other things. Struggle with Carrara, or hard and rare Parian marble, keepers of the pure contour.)

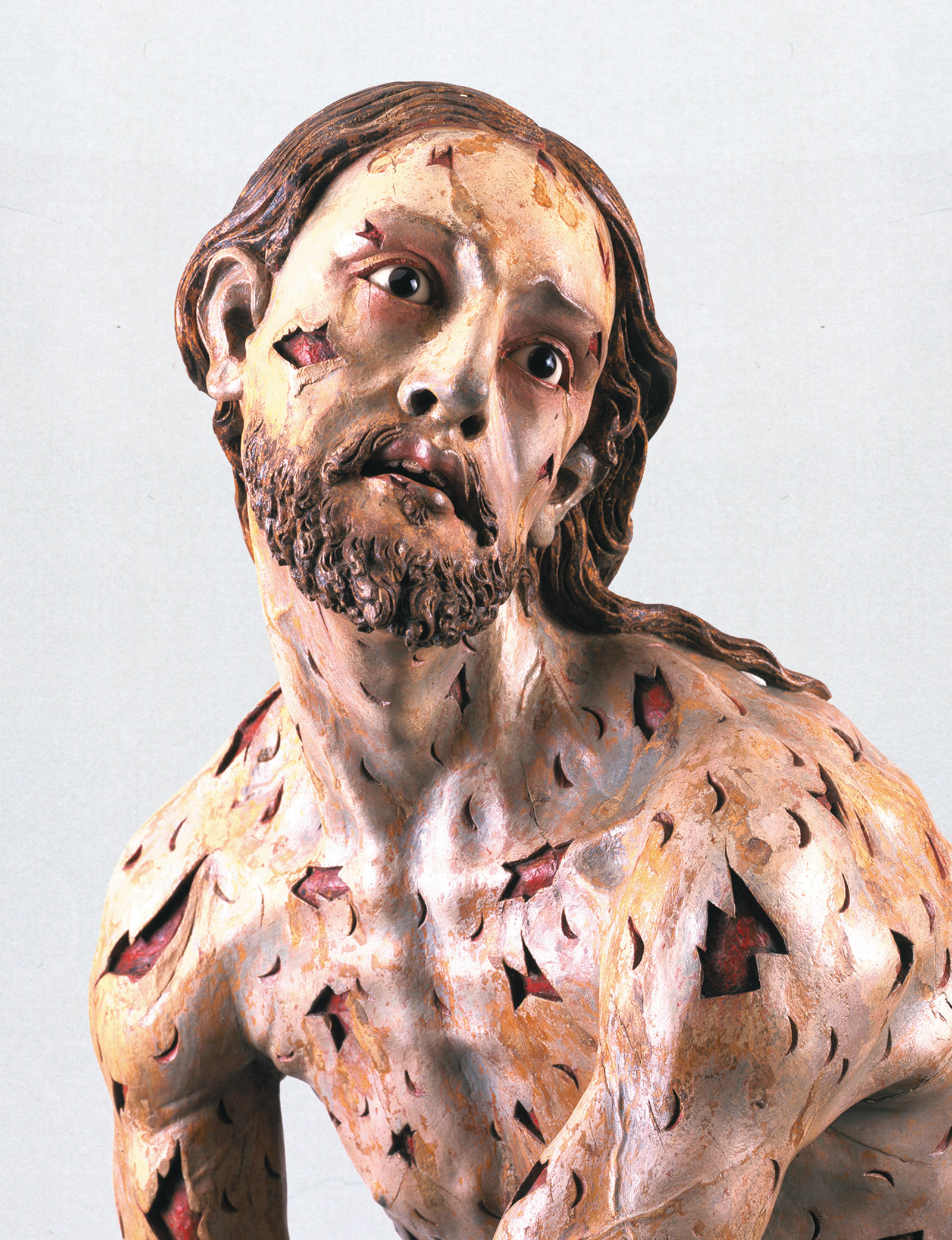

This is the Romantic idea of the artist taking the most challenging route possible. Marble, thinks Gautier, is rare, as is, in the same poem, onyx and agate. Watercolor is bad because easy. Enamel is good because it has to be fired. But painted wood or stone, when encountered, caused a profound unease. Marjorie Trusted, in her catalog of the Spanish sculptures at the Victoria and Albert Museum, quotes two British responses to Spanish polychromy. Here is George Dennis writing in 1839 of Málaga Cathedral:

While contemplating these statues, I was led to enquire why plain marble figures seem superior as works of art to this painted sculpture; which is undoubtedly the case. Is it the force of habit leading us to associate the coloured figures with the wax-work busts that in England adorn the barbers’ windows? It may be so in part, but I think not entirely. There seems to be a legitimate reason why plain sculpture, caeteris paribus, should be preferred to coloured. The latter is too natural—the colour imparts an air of life which destroys its ideality…. The very incompleteness of sculpture constitutes its peculiar excellence.

Richard Ford in 1845 says that Spanish works of sculpture

have a startling identity: the stone statues of monks actually seem petrifactions of a once living being…from being clothed and painted they are failures as works of art, strictly speaking, for they attempt too much. The essence of statuary is form, and to clothe a statue, said Byron, is like translating Dante: a marble statue never deceives; it is the colouring it that does, and is a trick beneath the severity of sculpture. The imitation of life may surprise, but…it can only please the ignorant and children…to whom the painted doll gives more pleasure than the Apollo Belvidere [sic].

Painted Spanish sculpture had flesh tones and realistic wounds and tears and glass eyes, and it gave Protestants the creeps. But here’s the thing: Italian sculptors of the Renaissance also colored their works and were seemingly happy to do so. If we tend to forget this, it may be because the evidence we are looking at has been rigged: painted terracottas of the Renaissance have been stripped of their color, just as innumerable wood carvings of the northern schools have been stripped and “antiqued” in a manner acceptable to past taste and the antiques trade. The art dealer Joseph Duveen liked the surfaces of his terracottas to be covered with a sort of brown gravy, so that’s what they got. But their original surfaces might have been prepared with a thin layer of white gesso and then painted in appropriate colors. Or, to the bafflement of later connoisseurs, they might have been painted to resemble bronze—a “trick beneath the severity of sculpture” indeed.

The closer one looks at the Italian sculptors of the Renaissance, the more one finds them getting up to what the Internet ads call these “weird little tricks.” In Siena Cathedral there was erected, in 1394, a monument to Gian Tedesco da Pietramala, which (the scholar Bruce Boucher tells us) “featured a horse and rider composed of wood, hay, and tow, covered with a mixture of clay combined with scraps of wool cloth, paste, and glue.” Mixed media perhaps. And this was not simply some temporary decoration (as for some festival or similar event). The equestrian figure lasted, we are told, well into the sixteenth century.

Advertisement

Not long after the Siena monument, in 1410, Donatello was commissioned to provide a huge statue (one estimate suggests it might have been over seventeen feet tall) depicting Joshua. The piece was for the open air, high up on one of the buttresses of the Duomo in Florence. A block of marble would be out of the question. The solution was to build a core out of molded bricks, cover it with gesso, and paint it white. It didn’t last forever, but it seems to have been still in place in 1586.

Marble-ish? Yes, from the ground it could have looked like marble. “Truth to materials”? No.

The first time I saw Donatello’s wooden statue of Saint Mary Magdalen, it was on a plinth in the Baptistry in Florence—memorably dark and fierce. Then came the flood of 1966, and the Magdalen was knocked off its plinth and submersed in filth and heating oil. Later it was cleaned and its coloring was found to be present beneath the grime, along with gilding of the hair and dress. Nobody had quite expected this. Sir John Pope-Hennessey wrote:

In this condition it spoke with the utmost power, but the surface was later painted with a preservative varnish, which has the effect of diminishing the rough handling of the wood and the emotive cutting of the head. A work that once looked like a ferocious Kamakura sculpture has been domesticated. But the brilliant white of the teeth, the surface of the hair and dress, and the flesh areas, not only in the head and hands and legs, but in the right thigh seen through the torn dress and in the firmly modeled left shoulder, still afford some impression of the effect it must originally have made.

Pope-Hennessey, in his monograph, illustrates the head of the Magdalen during cleaning, half of it colored and gilt, the other half obscured by the grime of ages.

But why should the Magdalen’s gilded hair and white teeth have come as a surprise, when we always knew that Donatello worked in other media besides bronze and marble? The answer lies in a kind of perceptual trick played on us by the history of taste. We might know that he did so, but a quiet voice in our ear whispers that, to the extent that he did use polychromy, he was a little less Donatello. He wasn’t fully himself as an artist. It is the same with Michelangelo. Yes, he carved and perhaps painted the wooden Santo Spirito crucifix, if you will. But he wasn’t quite there yet when he did it. That crucifix sat forgotten in some corridor in Santo Spirito, invisible even to scholars who came looking for it, because it didn’t look like the Michelangelo they were after. And it had been whitewashed several times, no doubt to conform to later taste.

The case of the della Robbia family illustrates perfectly the operation of this perceptual trick. Luca della Robbia, sculptor and ceramicist, gets past the internal censor if he is seen as confining his output to tasteful finishes in white and blue. But then the rest of the della Robbia family come along and ruin everything, adding more glazes, more colors to the mix. And soon—because this is a problem of taste but also a problem of genre—we have to pause to inquire whether we are still in the world of fine art, or is this a kind of Florentine street crockery?

Of course, we are still in the world of a fine art that is responsive to the exigencies of city life (How can a work of art survive the mud and grime of the street? Answer: by being glazed), and it is our unexamined prejudices that are getting in the way. Choices that may seem important to us (to work in color or not) must have been less important to a sculptor like Benedetto da Maiano, who received a commission for an altarpiece of the Annunciation. In preparation for this relief work he created separate terracotta figures, from which he carved the marble. Afterward, rather than let the terracotta figures go to waste, he or some associate assembled the terracottas and painted them, so as to form another altarpiece elsewhere. There was no either/or for Benedetto in this case. He could enjoy the benefits of both.

We have already seen the British visitor to Spain looking at polychrome works in a cathedral and thinking of the wax busts in barbershop windows, a genre that seems to have long since perished, along with so much else that was done in wax. It is a medium that permits a quite extraordinary verisimilitude, the fortune of Madame Tussaud makes plain. It is worth remembering (and worth taking time to answer the insidious inner voice insinuating that wax modeling is a peripheral activity in the unfolding story of art) that all sculptors who worked in bronze—until the technology changed—worked in wax. And rightly is it called the lost-wax process, since the results from it are mostly lost to view. But for the sculptors of the Renaissance the making of wax funeral effigies was a part of the job, just as the creation of wax reliefs on flat slices of slate, from which dies could be cast and medals struck, was part of the job.

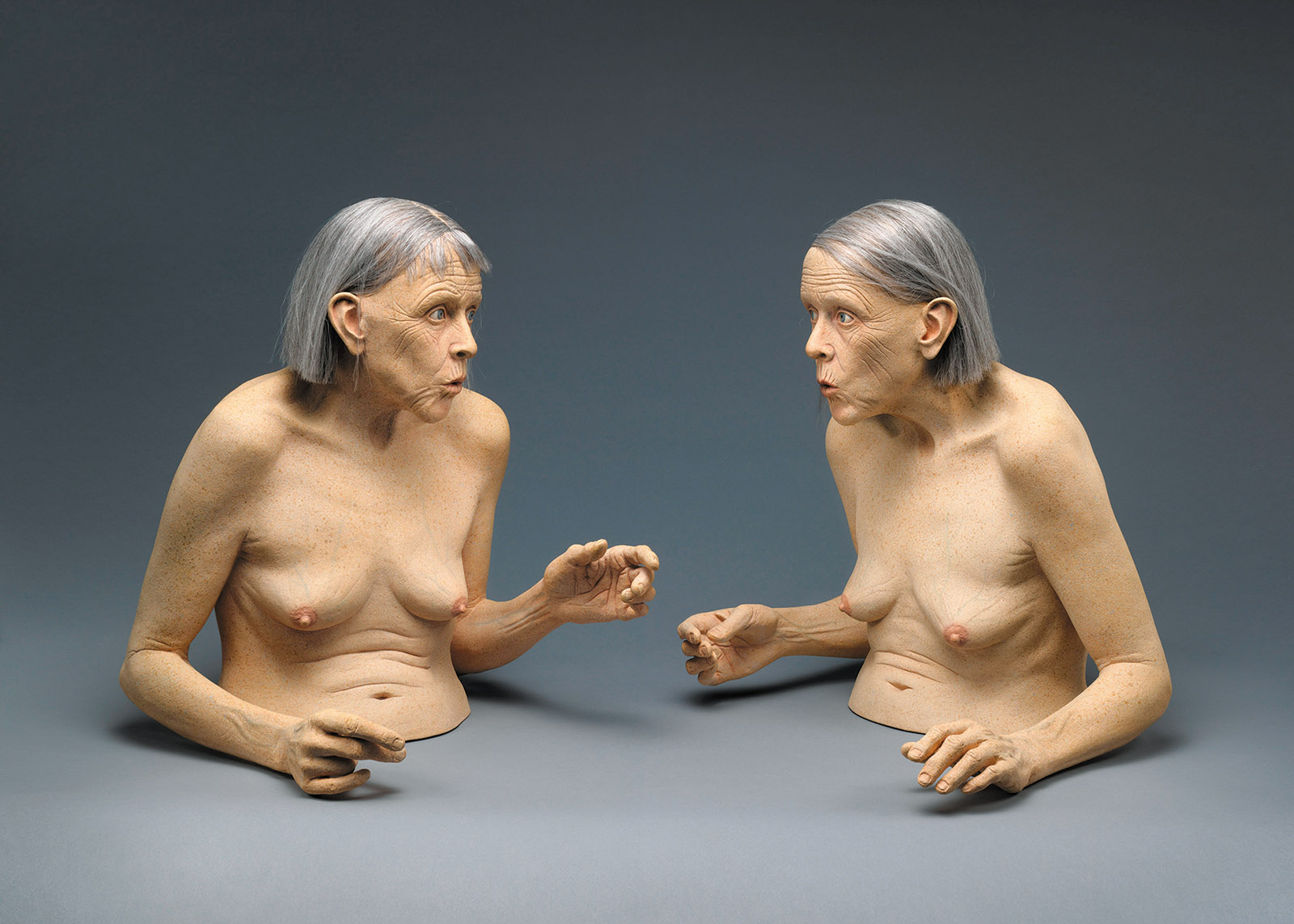

Color, said the Victorian visitor to Spain, “imparts an air of life which destroys [sculpture’s] ideality.” The Met Breuer exhibition assembles a range of cleverly chosen items that tend to impart that air of life—startlingly so. Donatello’s bust of Niccolò da Uzzano with its odd tilt of the head—does its “air of life” come from its being cast from life or from a death mask? Or does its coloration push it in the direction of the uncanny? I think not. I think it is the artist’s hand. And that extraordinary self-portrait bust by Johan Gregor van der Schardt (one of the treasures of the Rijksmuseum, and indeed of Northern European sculpture itself)—was there once more of this kind of thing in the world? Or was it a rare spirit who was prepared to assert his presence in this way? As rare as Dürer with his nude self-portrait.

To destroy sculpture’s ideality—that could stand as a motto for Bharti Kher’s cast of her stolid nude Mother, or for Duane Hanson’s slightly pot-bellied black Housepainter 1, pausing to contemplate the task ahead. In Elmgreen and Dragset’s The Experiment, a young boy in his underpants tries on high-heeled shoes and lipstick in front of a mirror. And in one of the star pieces on the contemporary list, Reza Aramesh’s Action 105: An Israeli soldier points his gun at the Palestinian youth asked to strip down as he stands at a military checkpoint along the separation barrier at the entrance of Bethlehem, March 2006, we see only the Palestinian youth, who has removed his sneakers and clothes, down to his shorts, and stands much like a Spanish saint but with an expression of dread. The figure is executed, we are surprised to learn, in hand-carved polychrome limewood, with glass eyes.

Spanish sculpture, for so long the least valued of the European schools, is much celebrated in the Met Breuer show. A magnificent recent acquisition by the Met is The Entombment of Christ, a small-scale devotional group by Luisa Roldán, who was known as La Roldana. It dates from 1700–1701. La Roldana was the modeler of these highly detailed and expressive figures in terracotta. Apparently her husband was responsible for painting them—an unusual arrangement surely. (Luke Syson in his catalog essay has an interesting section on women who modeled in wax.)

Such pieces hold their own remarkably well among contemporary works that share an “air of life,” such as the breathtaking last item in the show, Ron Mueck’s Old Woman in Bed—an essay in the shrinking and withdrawal of the dying from the world. One is reminded, confronted by this or by Paul McCarthy’s trouserless self-portrait on a lawnchair, of the recurring stories of sculptures that “seem to breathe.” In Lichfield Cathedral in England, it was always said of Sir Francis Chantrey’s white marble Sleeping Children that if you looked long enough you could see them breathe. And Robert Lowell recalls of Saint-Gaudens’s monument to Colonel Shaw and his black Civil War infantry:

Two months after marching through Boston,

half the regiment was dead;

at the dedication,

William James could almost hear the bronze Negroes breathe.

And here at the Met Breuer, well chosen, is a recreation of Madame Tussaud’s Sleeping Beauty (originally 1765), equipped with a little mechanism to mimic the rise and fall of a sleeper’s diaphragm.

We are reminded that we have seen the artist-creator of the human being on stage, when he features as a villain, in the ballet Coppelia and in the opera The Tales of Hoffmann. Both of these are based on E.T.A. Hoffmann’s story “The Sandman.” In the ballet, Dr. Coppelius’s villainy stems from his desire to make his doll fully human, by means of human sacrifice. The young man who falls in love with an automaton puts himself in peril. The creator of Frankenstein’s monster puts his own family immediately in peril. Pushing art too far comes across as a kind of hubris.

This rich collection of objects—from El Greco’s mannerist Pandora (small and easily missed, but how many people are aware of such sculptures by El Greco?) to Charles Ray’s absurdly assertive Male Mannequin (a standard window dresser’s model displaying the artist’s own generous genitalia)—is designed to provoke as much as to please. In the end, though, provocation is a mug’s game. Pleasure’s the thing—pleasure, thought, a sense of an argument reaching back in time, art that trespasses on the uncanny, that “imparts an air of life which destroys its ideality.”

This Issue

July 19, 2018

Tipping the Scales

Düssel…

A Work of Art