(The following is an excerpt from J.M. Coetzee’s new novel, Diary of a Bad Year, to be published in January 2008.)

ONE: STRONG OPINIONS

September 12, 2005—May 31, 2006

01. On the origins of the state

Every account of the origins of the state starts from the premise that “we”—not we the readers but some generic we so wide as to exclude no one—participate in its coming into being. But the fact is that the only “we” we know—ourselves and the people close to us—are born into the state; and our forebears too were born into the state as far back as we can trace. The state is always there before we are.

(How far back can we trace? In African thought, the consensus is that after the seventh generation we can no longer distinguish between history and myth.)

If, despite the evidence of our senses, we accept the premise that we or our forebears created the state, then we must also accept its entailment: that we or our forebears could have created the state in some other form, if we had chosen; perhaps, too, that we could change it if we collectively so decided. But the fact is that, even collectively, those who are “under” the state, who “belong to” the state, will find it very hard indeed to change its form; they—we—are certainly powerless to abolish it.

It is hardly in our power to change the form of the state and impossible to abolish it because, vis-à-vis the state, we are, precisely, powerless. In the myth of the founding of the state as set down by Thomas Hobbes, our descent into powerlessness was voluntary: in order to escape the violence of internecine warfare without end (reprisal upon reprisal, vengeance upon vengeance, the vendetta), we individually and severally yielded up to the state the right to use physical force (right is might, might is right), thereby entering the realm (the protection) of the law. Those who chose and choose to stay outside the compact become outlaw.

My first glimpse of her was in the laundry room. It was mid-morning on a quiet spring day and I was sitting, watching the washing go around, when this quite startling young woman walked in. Startling because the last thing I was expecting was such an apparition; also because the tomato-red shift she wore was so startling in its brevity.

The law protects the law-abiding citizen. It even protects to a degree the citizen who, without denying the force of the law, nevertheless uses force against his fellow citizen: the punishment prescribed for the offender must be condign with his offense. Even the enemy soldier, inasmuch as he is the representative of a rival state, shall not be put to death if captured. But there is no law to protect the outlaw, the man who takes up arms against his own state, that is to say, the state that claims him as its own.

Outside the state (the commonwealth, the statum civitatis), says Hobbes, the individual may feel he enjoys perfect liberty, but that liberty does him no good. Within the state, on the other hand,

every citizen retains as much liberty as he needs to live well in peace, [while] enough liberty is taken from others to remove the fear of them…. To sum up: outside the commonwealth is the empire of passions, war, fear, poverty, nastiness, solitude, barbarity, ignorance, savagery; within the commonwealth is the empire of reason, peace, security, wealth, splendor, society, good taste, the sciences and good-will.1

What the Hobbesian myth of origins does not mention is that the handover of power to the state is irreversible. The option is not open to us to change our minds, to decide that the monopoly on the exercise of force held by the state, codified in the law, is not what we wanted after all, that we would prefer to go back to a state of nature.

We are born subject. From the moment of our birth we are subject. One mark of this subjection is the certificate of birth. The perfected state holds and guards the monopoly of certifying birth. Either you are given (and carry with you) the certificate of the state, thereby acquiring an identity which during the course of your life enables the state to identify you and track you (track you down); or you do without an identity and condemn yourself to living outside the state like an animal (animals do not have identity papers).

The spectacle of me may have given her a start too: a crumpled old fellow in a corner who at first glance might have been a tramp off the street. Hello, she said coolly, and then went about her business, which was to empty two white canvas bags into a top-loader, bags in which male underwear seemed to predominate.

Not only may you not enter the state without certification: you are, in the eyes of the state, not dead until you are certified dead; and you can be certified dead only by an officer who himself (herself) holds state certification. The state pursues the certification of death with extraordinary thoroughness—witness the dispatch of a host of forensic scientists and bureaucrats to scrutinize and photograph and prod and poke the mountain of human corpses left behind by the great tsunami of December 2004 in order to establish their individual identities. No expense is spared to ensure that the census of subjects shall be complete and accurate.

Advertisement

Whether the citizen lives or dies is not a concern of the state. What matters to the state and its records is whether the citizen is alive or dead.

* * *

The Seven Samurai is a film in complete command of its medium yet naive enough to deal simply and directly with first things. Specifically it deals with the birth of the state, and it does so with Shakespearean clarity and comprehensiveness. In fact, what The Seven Samurai offers is no less than the Kurosawan theory of the origin of the state.

Nice day, I said. Yes, she said, with her back to me. Are you new? I said, meaning was she new to Sydenham Towers, though other meanings were possible too, Are you new on this earth?, for example. No, she said. How it creaks, getting a conversation going. I live on the ground floor, I said. I am allowed to make gambits like that, it will be put down to garrulity. Such a garrulous old man, she will remark to the owner of the pink shirt with the white collar, I had a hard time getting away from him, one doesn’t want to be rude. I live on the ground floor and have since 1995 and still I don’t know all my neighbors, I said. Yeah, she said, and no more, meaning, Yes, I hear what you say and I agree, it is tragic not to know who your neighbors are, but that is how it is in the big city and I have other things to attend to now, so could we let the present exchange of pleasantries die a natural death.

The story told in the film is of a village during a time of political disorder—a time when the state has in effect ceased to exist—and of the relations of the villagers with a troop of armed bandits. After years of descending upon the village like a storm, raping the women, killing those men who resist, and bearing away stored-up food supplies, the bandits hit on the idea of systematizing their visits, calling on the village just once a year to exact or extort tribute (tax). That is to say, the bandits cease being predators upon the village and become parasites instead.

One presumes that the bandits have other such “pacified” villages under their thumb, that they descend upon them in rotation, that in ensemble such villages constitute the bandits’ tax base. Very likely they have to fight off rival bands for control of specific villages, although we see none of this in the film.

The bandits have not yet begun to live among their subjects, having their wants taken care of day by day—that is to say, they have not yet turned the villagers into a slave population. Kurosawa is thus laying out for our consideration a very early stage in the growth of the state.

The main action of the film starts when the villagers conceive a plan of hiring their own band of hard men, the seven unemployed samurai of the title, to protect them from the bandits. The plan works, the bandits are defeated (the body of the film is taken up with skirmishes and battles), the samurai are victorious. Having seen how the protection and extortion system works, the samurai band, the new parasites, make an offer to the villagers: they will, at a price, take the village under their wing, that is to say, will take the place of the bandits. But in a rather wishful ending the villagers decline: they ask the samurai to leave, and the samurai comply.

She has black black hair, shapely bones. A certain golden glow to her skin, lambent might be the word. As for the bright red shift, that is perhaps not the item of attire she would have chosen if she were expecting strange male company in the laundry room at eleven in the morning on a weekday. Red shift and thongs. Thongs of the kind that go on the feet.

The Kurosawan story of the origin of the state is still played out in our times in Africa, where gangs of armed men grab power—that is to say, annex the national treasury and the mechanisms of taxing the population—do away with their rivals, and proclaim Year One. Though these African military gangs are often no larger or more powerful than the organized criminal gangs of Asia or Eastern Europe, their activities are respectfully covered in the media—even the Western media—under the heading of politics (world affairs) rather than crime.

Advertisement

One can cite examples of the birth or rebirth of the state from Europe too. In the vacuum of power left by the defeat of the armies of the Third Reich in 1944–1945, rival armed gangs scrambled to take charge of the newly liberated nations; who took power where was determined by who could call on what foreign army for backing.

Did anyone, in 1944, say to the French populace: Consider: the retreat of our German overlords means that for a brief moment we are ruled by no one. Do we want to end that moment, or do we perhaps want to perpetuate it—to become the first people in modern times to roll back the state? Let us, as French people, use our new and sudden freedom to debate the question without restraint. Perhaps some poet spoke the words; but if he did his voice must at once have been silenced by the armed gangs, who in this case and in all cases have more in common with each other than with the people.

* * *

In the days of kings, the subject was told: You used to be the subject of King A, now King A is dead and behold, you are the subject of King B. Then democracy arrived, and the subject was for the first time presented with a choice: Do you (collectively) want to be ruled by Citizen A or Citizen B?

As I watched her an ache, a metaphysical ache, crept over me that I did nothing to stem. And in an intuitive way she knew about it, knew that in the old man in the plastic chair in the corner there was something personal going on, something to do with age and regret and the tears of things. Which she did not particularly like, did not want to evoke, though it was a tribute to her, to her beauty and freshness as well as to the shortness of her dress. Had it come from someone different, had it had a simpler and blunter meaning, she might have been readier to give it a welcome; but from an old man its meaning was too diffuse and melancholy for a nice day when you are in a hurry to get the chores done.

Always the subject is presented with the accomplished fact: in the first case with the fact of his subjecthood, in the second with the fact of the choice. The form of the choice is not open to discussion. The ballot paper does not say: Do you want A or B or neither? It certainly never says: Do you want A or B or no one at all? The citizen who expresses his unhappiness with the form of choice on offer by the only means open to him—not voting, or else spoiling his ballot paper—is simply not counted, that is to say, is discounted, ignored.

Faced with a choice between A and B, given the kind of A and the kind of B who usually make it onto the ballot paper, most people, ordinary people, are in their hearts inclined to choose neither. But that is only an inclination, and the state does not deal in inclinations. Inclinations are not part of the currency of politics. What the state deals in are choices. The ordinary person would like to say: Some days I incline to A, some days to B, most days I just feel they should both go away; or else, Some of A and some of B, sometimes, and at other times neither A nor B but something quite different. The state shakes its head. You have to choose, says the state: A or B.

* * *

“Spreading democracy,” as is now being done by the United States in the Middle East, means spreading the rules of democracy. It means telling people that whereas formerly they had no choice, now they have a choice. Formerly they had A and nothing but A; now they have a choice between A and B. “Spreading freedom” means creating the conditions for people to choose freely between A and B. The spreading of freedom and the spreading of democracy go hand in hand. The people engaged in spreading freedom and democracy see no irony in the description of the process just given.

A week passed before I saw her again—in a well-designed apartment block like this, tracking one’s neighbors is not easy—and then only fleetingly as she passed through the front door in a flash of white slacks that showed off a derrière so near to perfect as to be angelic. God, grant me one wish before I die, I whispered; but then was overtaken with shame at the specificity of the wish, and withdrew it.

During the cold war, the explanation given by Western democratic states for the banning of their Communist parties was that a party whose stated aim is the destruction of the democratic process should not be allowed to participate in the democratic process, defined as choosing between A and B.

* * *

Why is it so hard to say anything about politics from outside politics? Why can there be no discourse about politics that is not itself political? To Aristotle the answer is that politics is built into human nature, that is, is part of our fate, as monarchy is the fate of bees. To strive for a systematic, suprapolitical discourse about politics is futile.

From Vinnie, who looks after the North Tower, I learn that she—whom I am prudent enough to describe to him not as the young woman in the alluringly short shift and now in the elegant white slacks, but as the young woman with the dark hair—is the wife or at least girlfriend of the pale, hurrying, plump, and ever-sweaty fellow whose path crosses mine now and again in the lobby and for whom my private name is Mr. Aberdeen; further, that she is not new in the customary sense of the word, having (together with Mr. A) occupied since January a prime unit on the top floor of this same North Tower.

02. On anarchism

When the phrase “the bastards” is used in Australia, its reference is understood on all sides. “The bastards” was once the convict’s term for the men who called themselves his betters and flogged him if he disagreed. Now “the bastards” are the politicians, the men and women who run the state. The problem: how to assert the legitimacy of the old perspective, the perspective from below, the convict’s perspective, when it is of the nature of that perspective to be illegitimate, against the law, against the bastards.

Opposition to the bastards, opposition to government in general under the banner of libertarianism, has acquired a bad name because all too often its roots lie in a reluctance to pay taxes. Whatever one’s views on paying tribute to the bastards, a strategic first step must be to distinguish oneself from that particular libertarian strain. How to do so? “Take half of what I own, take half of what I earn, I yield it to you; in return, leave me alone.” Would that be enough to prove one’s bona fides?

Michel de Montaigne’s young friend Étienne de La Boétie, writing in 1549, saw the passivity of populations vis-à-vis their rulers as first an acquired and then later an inherited vice, an obstinate “will to be ruled” that becomes so deep-rooted “that even the love of liberty comes to seem not quite as natural.”

Thank you, I said to Vinnie. In an ideal world I might have thought of a way to interrogate him further (Which unit? Under what name?) without unseemliness. But this is not an ideal world.

Her connection with the no doubt freckle-backed Mr. Aberdeen is a great disappointment. It pains me to think of the two of them side by side, that is to say, side by side in bed, since that is what counts, finally. Not just because of the insult—the insult to natural justice—of such a dull man in possession of so celestial a paramour, but because of what the fruit of their union might look like, her golden glow quite washed out by his Celtic pallor.

It is incredible to see how the populace, once they have been subjected, fall suddenly into such profound forgetfulness of their earlier independence that it becomes impossible for them to rouse themselves and recover it; in fact, they proceed to serve so much without prompting, so freely, that one would say, on the face of it, they have not lost their liberty but won their servitude. It may be true that, to begin with, one serves because one has to, because one is constrained to by force; but those who come later serve without regret, and perform of their own free will what their predecessors performed under constraint. So it happens that men, born under the yoke, brought up in servitude, are content to live as they were born…assuming as their natural state the conditions under which they were born.2

Well said. Nevertheless, in an important respect La Boétie gets it wrong. The alternatives are not placid servitude on the one hand and revolt against servitude on the other. There is a third way, chosen by thousands and millions of people every day. It is the way of quietism, of willed obscurity, of inner emigration.

Days could be spent in devising felicitous coincidences to allow the brief exchange in the laundry room to be picked up elsewhere. But life is too short for plotting. So let me simply say that the second intersection of our paths took place in a public park, the park across the street, where I spotted her taking her ease under an extravagantly large sun hat, browsing through a magazine. She was in a more amiable mood this time, less curt with me; I was able to confirm from her own lips that she was for the present without significant occupation, or, as she put it, between jobs: hence the sun hat, hence the magazine, hence the languor of her days. Her previous employment, she said, had been in the hospitality industry; she would in due course (but there was no hurry) be seeking redeployment in the same field.

03. On democracy

The main problem in the life of the state is the problem of succession: how to ensure that power will be passed from one set of hands to the next without a contest of arms.

In comfortable times we forget how terrible civil war is, how rapidly it descends into mindless slaughter. René Girard’s fable of the warring twins is pertinent: the fewer the substantive differences between the two parties, the more bitter their mutual hatred. One recalls Daniel Defoe’s comment on religious strife in England: that adherents of the national church would swear to their detestation of papists and popery not knowing whether the Pope was a man or a horse.

Early solutions to the problem of succession have a distinctly arbitrary look: on the ruler’s death, his firstborn male child will succeed to power, for example. The advantage of the firstborn male solution is that the firstborn male is unique; the disadvantage is that the firstborn male in question may have no aptitude to rule. The annals of kingdoms are rife with stories of incompetent princes, to say nothing of kings unable to father sons.

From a practical point of view, it does not matter how succession is managed as long as it does not precipitate the country into civil war. A scheme in which many (though usually only two) candidates for leadership present themselves to the populace and subject themselves to a ballot is only one of a score that an inventive mind might come up with. It is not the scheme itself that matters, but consensus to adopt the scheme and abide by the results. Thus in itself succession by the firstborn is neither better nor worse than succession by democratic election. But to live in democratic times means to live in times when only the democratic scheme has currency and prestige.

All the while she was conveying this rather desultory information the air around us positively crackled with a current that could not have come from me, I do not exude currents any more, must therefore have come from her and been aimed at no one in particular, just released into the environment. Hospitality, she repeated, or else perhaps human resources, she had some experience in human resources (whatever those might be) too; and again the shadow of the ache passed over me, the ache I alluded to earlier, of a metaphysical or at least post-physical kind.

As during the time of kings it would have been naive to think that the king’s firstborn son would be the fittest to rule, so in our time it is naive to think that the democratically elected ruler will be the fittest. The rule of succession is not a formula for identifying the best ruler, it is a formula for conferring legitimacy on someone or other and thus forestalling civil conflict. The electorate—the demos—believes that its task is to choose the best man, but in truth its task is much simpler: to anoint a man (vox populi vox dei), it does not matter whom. Counting ballots may seem to be a means of finding which is the true (that is, the loudest) vox populi; but the power of the ballot-count formula, like the power of the formula of the firstborn male, lies in the fact that it is objective, unambiguous, outside the field of political contestation. The toss of a coin would be equally objective, equally unambiguous, equally incontestable, and could therefore equally well be claimed (as it has been claimed) to represent vox dei. We do not choose our rulers by the toss of a coin—tossing coins is associated with the low-status activity of gambling—but who would dare to claim that the world would be in a worse state than it is if rulers had from the beginning of time been chosen by the method of the coin?

I imagine, as I write these words, that I am arguing this antidemocratic case to a skeptical reader who will continually be comparing my claims with the facts on the ground: Does what I say about democracy square with the facts about democratic Australia, the democratic United States, and so forth? The reader should bear it in mind that for every democratic Australia there are two Belaruses or Chads or Fijis or Colombias that likewise subscribe to the formula of the ballot count.

Australia is by most standards an advanced democracy. It is also a land where cynicism about politics and contempt for politicians abound. But such cynicism and contempt are quite comfortably accommodated within the system. If you have reservations about the system and want to change it, the democratic argument goes, do so within the system: put yourself forward as a candidate for political office, subject yourself to the scrutiny and the vote of fellow citizens. Democracy does not allow for politics outside the democratic system. In this sense, democracy is totalitarian.

In the meantime, she went on, I help Alan with reports and so forth, so he can claim me as a secretarial resource.

Alan, I said.

If you take issue with democracy in times when everyone claims to be heart and soul a democrat, you run the risk of losing touch with reality. To regain touch, you must at every moment remind yourself of what it is like to come face to face with the state—the democratic state or any other—in the person of the state official. Then ask yourself: Who serves whom? Who is the servant, who the master?

Alan, she said, my partner. And she gave me a look. The look did not say, Yes, I am to all intents and purposes a married woman, so if you pursue the course you have in mind it will be a matter of clandestine adultery, with all the risks and thrills pertaining thereto, nothing like that, on the contrary it said, You seem to think I am some sort of child, do I need to point out I am not a child at all?

I too am in need of a secretary, I said, grasping the nettle.

Yes? she said.

04. On Machiavelli

On talk-back radio ordinary members of the public have been calling in to say that, while they concede that torture is in general a bad thing, it may nonetheless sometimes be necessary. Some even advance the proposition that we may have to do evil for the sake of a greater good. In general they are scornful of absolutist opponents of torture: such people, they say, do not have their feet on the ground, do not live in the real world.

Machiavelli says that if as a ruler you accept that your every action must pass moral scrutiny, you will without fail be defeated by an opponent who submits to no such moral test. To hold on to power, you have not only to master the crafts of deception and treachery but to be prepared to use them where necessary.

Necessity, necessità, is Machiavelli’s guiding principle. The old, pre-Machiavellian position was that the moral law was supreme. If it so happened that the moral law was sometimes broken, that was unfortunate, but rulers were merely human, after all. The new, Machiavellian position is that infringing the moral law is justified when it is necessary.

Thus is inaugurated the dualism of modern political culture, which simultaneously upholds absolute and relative standards of value. The modern state appeals to morality, to religion, and to natural law as the ideological foundation of its existence. At the same time it is prepared to infringe any or all of these in the interest of self-preservation.

Yes? she said.

Yes, I said, I happen to be a writer by profession, and I have a major deadline to meet, as a consequence of which I need someone to type a manuscript for me and perhaps do a little editing as well and generally make the whole thing shipshape.

She looked blank.

Neat and orderly and readable, I mean, I said.

Use someone from a bureau, she said. There is a bureau on King Street that Alan’s company uses when they have urgent work.

Machiavelli does not deny that the claims morality makes on us are absolute. At the same time he asserts that in the interest of the State the ruler “is often obliged [necessitato] to act without loyalty, without mercy, without humanity, and without religion.”3

The kind of person who calls talk-back radio and justifies the use of torture in the interrogation of prisoners holds the double standard in his mind in exactly the same way: without in the least denying the absolute claims of the Christian ethic (love thy neighbor as thyself), such a person approves freeing the hands of the authorities—the army, the secret police—to do whatever may be necessary to protect the public from enemies of the state.

The typical reaction of liberal intellectuals is to seize on the contradiction here: How can something be both wrong and right, or at least both wrong and OK, at the same time? What liberal intellectuals fail to see is that this so-called contradiction expresses the quintessence of the Machiavellian and therefore the modern, a quintessence that has been thoroughly absorbed by the man in the street. The world is ruled by necessity, says the man in the street, not by some abstract moral code. We have to do what we have to do.

If you wish to counter the man in the street, it cannot be by appeal to moral principles, much less by demanding that people should run their lives in such a way that there are no contradictions between what they say and what they do. Ordinary life is full of contradictions; ordinary people are used to accommodating them. Rather, you must attack the metaphysical, supra-empirical status of necessità and show that to be fraudulent.

I don’t need someone from a bureau, I said. I need someone who can pick up installments and get them back to me speedily. That person should also have a feel, an intuitive feel, for what I am trying to do. Can I perhaps interest you in the work, since we are near neighbors and since you are, as you say, between jobs? I will pay, I said, and I mentioned a rate per hour which, even if she had once been the tsarina of hospitality, must have given her pause to reflect. Because of the urgency, I said. Because of the looming deadline.

05. On terrorism

The Australian parliament is about to enact antiterrorist legislation whose effect will be to suspend a range of civil liberties indefinitely into the future. The word hysterical has been used to describe the response to terror attacks by the governments of the United States, Britain, and now Australia. It is not a bad word, not undescriptive, but it has no explanatory power. Why should our rulers, normally phlegmatic men, react with sudden hysteria to the pinpricks of terrorism when for decades they were able to go about their everyday business unruffled, in full awareness that in a deep bunker somewhere in the Urals an enemy watched and waited with a finger on a button, ready if provoked to wipe them and their cities from the face of the earth?

One explanation on offer is that the new foe is irrational. The old Soviet foes might have been cunning and even devilish, but they were not irrational. They played the game of nuclear diplomacy as they played the game of chess: the so-called nuclear option might be included in their repertoire of moves, but the decision to take it would ultimately be rational (decision-making based on probability theory being counted here as eminently rational, though by its very nature it involves making gambles, taking chances), as would decisions made in the West. Therefore the game would be played by the same rules on both sides.

An intuitive feel: those were my words. They were a gamble, a shot in the dark, but they worked. What self-respecting woman would want to deny she has an intuitive feel? Thus has it come about that my opinions, in all their drafts and revisions, are to pass under the eye and through the hands of Anya (her name), of Alan and Anya, A & A, unit 2514, even though the Anya in question has never done a stitch of editing in her life and even though Bruno Geistler of Mittwoch Verlag GmbH has people on his staff perfectly capable of turning dictaphone tapes in English into a shipshape manuscript in German.

I stood up. I will leave you now, I said, to get on with your reading. If I had had a hat I would have doffed it, it would have been the right old-world gesture for the occasion.

Don’t go yet, she said. Tell me first, what sort of book is this going to be?

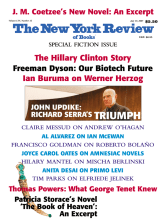

This Issue

July 19, 2007