The invention of the microscope in the seventeenth century revealed a miniature world no less vast and complicated than the depths of the starry heavens, themselves gloriously unveiled not long before by the telescope. Creatures previously invisible to human eyes proved to be crafted in detail as marvelous as that of any visible plant or beast, a fact that threw religion and science (in those days still known as natural philosophy) into an existential confusion, from which neither discipline has yet emerged entirely. It was one thing to discover new continents or new constellations, and quite another to discover, as Antonie van Leeuwenhoek—the Dutch inventor of the microscope—did with some horror, that whole kingdoms of “animalcules” were carrying on their lives within his own mouth.

One of the chief confusions presented by these tiny creatures was their place in the ranks of animal and vegetable. In 1705, when the erudite Swede Olof Rudbeck Junior published his biblical study The Selah Bird: Neither Bird nor Locust,1 his readers were still as likely as the ancient Hebrews to see bugs and birds as essentially similar creatures. The ability to fly was their most evident common quality, but Rudbeck’s contemporaries were also close to reaching a consensus that birds and insects shared another characteristic: they hatched from eggs rather than springing up spontaneously from substances like straw, sweat, and dung, or from the fertilizing power of sunbeams—the Florentine doctor Francesco Redi had put that controversy to rest in 1668, with the help of his powerful microscope, by finding fly eggs in a cow pat. To make matters still more confusing, the newborn beasts emerging from both bird and insect eggs often looked radically different from their parents.

By current standards, Francesco Redi’s minute examination of dung, like Van Leeuwenhoek’s examinations of scrapings from his teeth, come nearer to scientific method than Olof Rudbeck Junior’s minute examination of the Bible to shed light on the Selah bird (which he thought was actually a fish) while showing that the Swedish language was descended from Hebrew. Yet all those men, in their day, were regarded as highly competent natural philosophers. In many respects, another of their contemporaries, German-born Maria Sibylla Merian, enjoyed the same reputation for competence. Like Redi, Merian devoted much of her attention to the lower links of the Great Chain of Being; like Rudbeck, she financed her own research by ingenious entrepreneurship, eventually setting up her two daughters in the family business much as Olof Rudbeck Junior had been set up by his remarkable father Olof Senior, discoverer of the lymphatic system, anatomist, architect, fire chief, and purveyor of herring to the city of Uppsala (as well as the originator of Olof Junior’s peculiar ideas about the Swedes and the Bible).

Yet unlike Redi, who was as rooted in Florence as the Rudbecks were rooted in Uppsala, Maria Sibylla Merian spent her life in different parts of Germany, South America, and the Netherlands, and she carried out her investigations of nature without benefit of either optical instruments or a university degree (the first woman to earn one, Elena Cornaro Piscopia of Venice, took her laurea in mathematics from the University of Padua in 1678). Rather than coming to her interest in natural philosophy as a medical doctor (as did Redi and the Rubecks, father and son), she came to it as an artist, and communicated her results in images of plants, flowers, and insects, more than words. It is tempting now to compare Merian’s working method, with its emphasis on infinite patience, close attention to physical surroundings, and extreme intellectual independence, with that of pioneering women scientists like Jane Goodall or Barbara McClintock, but her story is more complicated than that. She was also peculiarly a child of her times and her surroundings, albeit a child with a large and emancipating talent.

Unlike most natural philosophers, decidedly an upper-class group, Maria Sibylla Merian—like the pharmacist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek—came from the world of middle-class business. This was a setting in which men, women, and children worked together, albeit with different duties, and where women might learn to maneuver in the marketplace as skillfully as men did. At the time of her birth in 1647, Maria Sibylla’s father, Matthäus Merian, was perhaps the most illustrious publisher in Frankfurt, a city already long renowned for its book fair and for its religious tolerance. This tolerance had first attracted the Calvinist publisher Theodor de Bry in the late sixteenth century when he fled Catholic persecution in Belgium, and soon de Bry’s print shop in Frankfurt had become famous for its illustrated books. The shop and its assets (printing machines, type, and extremely valuable engraved copper plates) passed eventually to de Bry’s son Johann Theodor, and it was the younger de Bry, in turn, who hired the Swiss engraver Matthäus Merian as an assistant. Merian, himself a Calvinist refugee, flourished, married his employer’s daughter Maria Magdalena, and, as their children came along, inserted them into the family enterprise. In 1623, Matthäus Merian, his wife, and their six children took charge of the shop.

Advertisement

Maria Sibylla was the child of the widowed Merian’s second wife, Johanna Sibylla Heim. The elderly father doted on his clever little daughter, predicting that she would bring continuing fame to the name of Merian; so, apparently, did her half-brothers Matthäus and Caspar, twenty years her senior. Although Mattäus Senior died when Maria Sibylla was only three, she would grow up immersed in the family’s world of painting, engraving, books, and salesmanship.

Johanna Sibylla Heim also remarried shortly after becoming a widow; her new husband, Jacob Marrel, was a German-born artist who had worked for years in Utrecht, specializing in decorative painting: flowers, still lifes, and views of cities. Although he came from a prominent Nuremberg clan, his social rank was somewhat below the Merians’. A widower with two apprentices and three children of his own, Marrel continued Maria Sibylla’s artistic training, by this time, apparently, against her mother’s wishes—but then Johanna Sibylla was one of the only members of this large extended family who lacked artistic skill. In 1658 the apprentice Johann Andreas Graff made a little drawing of the household at work, showing Maria Sibylla’s fourteen-year-old stepsister Sara bending intently over her embroidery frame, a painter’s easel propped behind her against a wall, two leaded windows casting light on her work.

Eleven-year-old Maria Sibylla, like Sara, was already putting her own hand to painting, engraving, and embroidery, both its design and its execution. Families like hers put every available member to work; for that reason, men and women tended to marry for the first time fairly late, in their mid-twenties, and, if bereaved, to remarry not long after losing a spouse. Above all, Maria Sibylla’s two extended families taught her that art was a business. The symbol of the Merian firm was a stork with a snake in its beak above the Latin motto Pietas Contenta Lucratur—“industrious piety pays.” The only surviving portrait of Maria Sibylla herself, engraved when she was a successful entrepreneur in her sixties, shows that Merian stork displayed prominently behind her. Industrious piety had paid off handsomely, helped along by a strong dose of Calvinist thrift.

Until recently, art historians and museum curators often relegated flower paintings, not to mention embroidery patterns, to the ranks of “minor arts,” despite strong evidence of the value these skills enjoyed in their own day. The idea of “minor arts” reflects the continuing commanding influence (thanks in great measure to Bernard Berenson) of the sixteenth-century artist and writer Giorgio Vasari, whose endlessly entertaining Lives of the Artists (with editions in 1550 and 1568) enshrined history painting as the pinnacle of the visual arts and Michelangelo as their undisputed master.

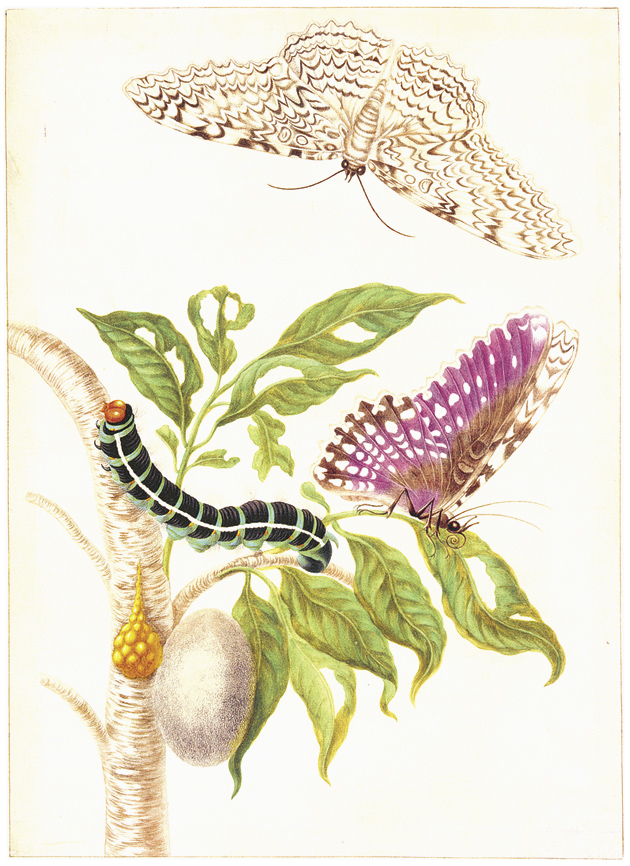

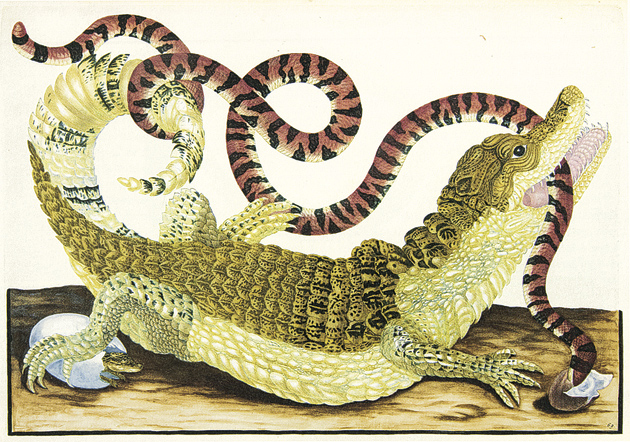

In such company, Maria Sibylla Merian’s renderings of plants and animals, with their crystalline accuracy, consigned her for a long time to the realm of scientific illustration rather than art. Fortunately, the Rembrandt House Museum in Amsterdam and the Getty Museum in Brentwood took a different view this past year with the exhibition “Maria Sibylla Merian & Daughters: Women of Art and Science.” From this beguiling presentation, it is clear at once that the large dynasty of painters, publishers, and engravers that produced and sustained Merian was as consciously aware of its artistic status as was Caravaggio—whom her stepfather Jacob Marrel apparently took as his idol, and whose view of still life shows some profound similarities with that of Maria Sibylla herself. Ranged alongside the work of her mentors, from Theodor de Bry’s printed books to Jacob Marrel’s flower paintings, Maria Sibylla Merian’s own creations reveal the richness of her cultural surroundings, and her own individuality emerges beyond dispute—in vibrant color. There is no question that she was an artist. Her disquieting view of life in all its forms has carefully, cleverly shaped every one of the images that seem, so deceptively, to present intimate, dispassionate snapshots of reality.

Inevitably, perhaps, given her northern milieu, Maria Sibylla’s still-life style reflects the incomparable precision of Albrecht Dürer and Joris Hofenagel—the northern European tradition—rather than the fierce dynamism of Leonardo. On the other hand, her version of the pigment known as cochineal red, a concoction made from the carapaces of a certain kind of beetle, eventually achieved an electric intensity that has almost no equal; only the Italian architect Felice della Greca, who worked in Rome in the 1650s, ever mixed cochineal red with oranges and purples in such boldly fluorescent combinations, and he drew buildings and cityscapes rather than insects, birds, and flowers. Marrel himself had a distinctively different, and more subdued, sense of color; his chief gift to his stepdaughter may have been his fascination with the little creatures—the worms, birds, and insects—that give his flower paintings a shiver of intense but fleeting liveliness.

Advertisement

Marrel’s career as a flower painter coincided with the Dutch tulip craze and the precipitous drop in prices that occurred during February and March 1636, an event whose catastrophic effects, as Anne Goldgar has shown in her recent study Tulipmania,2 were not so catastrophic after all. In fact, after settling on a reasonable price structure in the spring of 1636, the tulip trade bustled its way into an enduring place in the world’s markets. Jacob Marrel, like every other painter working in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century, knew his tulip breeds well, and portrayed them with a velvety softness, especially the prized white tulips shot with red, bunched together with fat, shocking pink roses and delicate purple irises, as evanescent as tulips, far more delicate, and almost as valuable.

Marrel and his clients also turned appreciative eyes on the other exotic plants that the Dutch East India Company (and its less successful West India counterpart) brought back along with their precious cargoes of spice: orange-blossomed crown imperials, peonies in shades ranging from violet to deep red. Dutch gardens displayed individual specimens of these plants in splendid isolation on pedestals of soil. The gardens of seventeenth-century Germany strove to keep pace with the trendsetters in the Netherlands, and there is reason to think, as Ella Reitsma shows in her catalog of the Merian exhibition, that the Merians and Jacob Marrel knew a few of the great gardens near Frankfurt.

In the absence of modern pesticides, these gardens also attracted a thriving community of animals, feeding on and sheltering beneath the vegetation. Some painters of still life, like the ancient Romans, create idyllic bouquets or magical gardens where flowers from every season burst into simultaneous perfect bloom, untouched by either time or hungry caterpillars; these are the immortal flowers of the gods and their shrines, for whom the passage of the seasons does not apply. Other painters, like Caravaggio, register the passage of time in brown, crinkled leaves, bruised fruit, and other signs of mortal growth and decay. Jacob Marrel’s lush compositions always record the shared existence of plant and animal; most of his sfumato flowers are beaded with bright little insects, their movements carefully observed by a frog or lizard poised to pounce, or a spider sitting in its carefully strung web. At the same time, Marrel’s animals pose rather than dine on his painted blossoms; he will show the occasional dropped leaf, but the signs of decay, like his awareness of the food chain, go no further than a decorous hint.

Maria Sibylla Merian’s paintings are another matter altogether. Her lines are as crisp as Marrel’s are muted; she draws with the clinical precision of Dürer or Hofenagel, but at the same time her saturated colors collide in daring, almost fluorescent contrasts. Rather than showing animal and vegetable at some celestially perfect moment, she combines the different stages of growth and decay, collapsing an expanse of time into a single image. Her flowers will appear on the same branch as buds, as new blossoms, full-blown, withered, gone to fruit. Leaves sprout, flourish, go brown, die, and drop, many of them half-eaten by caterpillars. The insects, too, are shown as they pass through every stage of their strange cyclical lives. Like Caravaggio before her, she registers the passage of time by documenting several of its phases, calling attention to the immanent imperfection of it all.

But Maria Sibylla Merian’s scrutiny of nature’s transience took on a peculiarly seventeenth-century focus; in these first years of the scientific revolution, her interest was, in every way, scientific. When she was thirteen, Maria Sibylla began growing caterpillars and studying their metamorphosis into butterflies. She had always collected worms and insects for her stepfather Marrel to use in his compositions; but in her teens she began to turn those collecting expeditions into a process of systematic research that would engross her ever afterward. An eager chronicler of insects and their lives, she never wrote much about herself. She kept no diary but she left a “Study Book,” a lavishly illustrated record of her investigations into natural philosophy—indeed, in both her Study Book and in her published volumes, her pictures usually speak more willingly than her words. We can therefore only guess at the reasons that drove her to choose the series of steps that would ultimately add up to a life dominated by its own continual process of metamorphosis.

At first, Maria Sibylla Merian’s life ran along perfectly conventional lines. The apprentice Andreas Graff returned to Frankfurt from Italy in 1664, and they married in 1665. At twenty-eight, he was ready to become a master in his own right, but by guild law he needed to marry in order to do so. Maria Sibylla, at seventeen, was a young bride, but her later actions would reveal an unusually independent spirit. In 1668, she bore a daughter, Johanna Helena; soon after, the young family moved to Graff’s native Nuremberg, where they would spend the next fourteen years. Maria Sibylla continued to develop her research on insects, the only unusual aspect of her industrious existence; in Florence, meanwhile, Francesco Redi had begun to publish his own pioneering investigations. Unlike Redi, who relied on a vast network of learned correspondence to bolster his published work, Maria Sibylla Merian communicated her discoveries by exchanging pictures.

Her first publication, the New Book of Flowers, was primarily meant to supply patterns for embroidery, but already she used imagery to chronicle the shape-shifting lives of plants and insects. She gathered her own set of students around her, respectable young women who learned to ply both paintbrush and needle as she did herself. In 1678, the Graffs produced a second daughter, Dorothea Maria. One year later, in 1679, Maria Sibylla published her research on caterpillars in a large folio volume, illustrated with her own engravings, images so accurate that readers could almost forget how beautiful they were. At least one copy of Caterpillars, Their Wondrous Transformation and Peculiar Nourishment from Flowers, or Big Caterpillar Book, now preserved in St. Petersburg, was probably hand-colored by the author herself. Its preface gives warm thanks to “my dear husband” for his help with rendering the flowers.

Jacob Marrel died in 1681. The Graff family moved back to Frankfurt, ostensibly to take care of Maria Sibylla’s widowed mother, but her Study Book would note that this return also obeyed a “call from God.” A second edition of the caterpillar book followed from her native city. And then, in 1685, Andreas Graff returned to Nuremberg alone. Something had gone badly wrong with the marriage. The “dear husband” of twenty years was no longer a person his wife wanted around her.

The conflict may have had religion at its root. Graff was probably a Lutheran. Maria Sibylla was certainly a Calvinist, of an increasingly radical stripe: religious radicalism and Messianic movements among Catholics, Protestants, and Jews alike were a common phenomenon in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. At some point the Merian family, especially her half-brother Caspar, had come under the sway of a Pietist preacher named Jean de Labadie, a former Catholic who urged his followers within the Calvinist fold to withdraw from the corrupt world and live together in Christian simplicity. Caspar entered a Labadist colony, moving to the chilly Frisian borderland village of Wiewert between the Netherlands and Germany to supervise its printing press. In 1686, together with her mother and her two daughters, aged seven and eighteen, Maria Sibylla set out to join him. Pietism, with its emphasis on an individual relationship with God, gave women greater authority to read and interpret Scripture than the larger Christian denominations; that authority may have appealed to a woman who had by now demonstrated unusual independence.

Maria Sibylla may also, of course, have been looking for a plausible escape from married life. Graff had other ideas. He would follow her to Wiewert, and even try to join the Labadist colony. When it rejected his application, he lived for a time on the outskirts of the village, growing thin and haggard. At last, he went away. The turmoil of that separation, and the sudden death of Caspar, kept Maria Sibylla away from her Study Book for the next two years; the simple communal life must have consumed all the energy not spent on caring for her mother and daughters.

The Labadist community at Wiewert was not the only one to arise in the latter part of the seventeenth century. Another group of intrepid Labadist settlers had reached the Dutch colony of Suriname, where they set up a village in the South American rain forest. When Maria Sibylla at last resumed her insect studies in Wiewert, she could supplement them with news from this distant outpost of the Pietist world, not to mention news from Amsterdam itself, where women enjoyed far more extensive legal rights than their German counterparts, and ships brought in commodities, people, and ideas from every corner of the globe. For a woman accustomed to the bustling cities of Frankfurt and Nuremberg, the charms of Wiewert’s simple life inevitably paled before the attractions of Golden Age Amsterdam. There may have been no more promising place in Europe for an independent businesswoman to set up shop—especially a businesswoman intent on revising certain aspects of her past.

Her mother’s death in 1690 gave her the excuse to leave Wiewert and set up shop in Amsterdam under her maiden name. In 1692, her elder daughter, Johanna Helena, married a Dutch businessman, Jacob Hendrrik Herolt, a Labadist symphathizer with connections to Suriname, and in Nuremberg, Andreas Graff filed for divorce. Maria Sibylla was independent at last, the mistress of her own workshop, with her two daughters and Jacob Herolt as her partners. Her work on insects could thrive in Amsterdam as nowhere before; ships brought in specimens of plants and animals from all over the world, and the city was filled with learned conversations. Unlike her more aristocratic colleagues, however, Merian had to earn a living. Ultimately, everything in her shop, except perhaps her Study Book, was for sale. As a result, one scholarly visitor reported being repelled by her venality. She could not have afforded to be otherwise.

Yet even Amsterdam was not big enough to contain Maria Sibylla Merian’s curiosity. The city’s active social life cut into her study time as drastically as the good works at Wiewert, and thus in 1699, at the age of fifty-two, a successful artist, engraver, publisher, and natural philosopher, she resolved to pursue her insect studies in the field. Together with her daughter Dorothea, she shipped out for Suriname, not to the Labadist colony, but to the Dutch garrison city of Paramaribo. Mother and daughter would spend two years in the tropics, observing insects, birds, reptiles, and amphibians under truly uncomfortable conditions. Finally, even industrious Maria Sibylla had to concede that her health would not survive a projected five-year field expedition. Mother and daughter returned to Amsterdam with a native housemaid and many containers of specimens. Merian’s next book, The Metamorphosis of the Insects of Suriname, issued from Amsterdam, would be truly global in its scope.

The exhibition ” Maria Sibylla Merian and Daughters,” like its catalog, is concentrated for the first time on mother and daughters as a group. Maria Sibylla herself provided the focus for a long chapter in Natalie Zemon Davis’s Women on the Margins,3 where Davis noted in her introduction that it was not quite right to term Merian a marginal figure. In a certain sense, of course, the cutting edge is a margin, too, and often the margin of choice for women (and men) of extraordinary ambition. From the perspective of contemporary biology, Kim Todd has also treated Merian in a ruminating, speculative, hugely readable biography, Chrysalis. Ella Reitsma’s catalog for ” Maria Sibylla Merian & Daughters” takes a similarly personal view, detailing the author’s own growing interest in Merian’s meticulous art. In each case, although in quite different ways, a conspicuous—and illuminating—personal involvement on the part of these authors compensates for the frustrating dearth of information we have about what really made Maria Sibylla Merian tick.

Reitsma’s meticulously close examination of the paintings, engravings, books, and colored prints from the Merian workshops makes it easy for readers (helped by marvelous illustrations) to see the distinct sensibilities of all the different members of this skilled, industrious extended family, in which Maria Sibylla’s is beyond doubt the supreme talent. Like their mother, the Merian daughters would take off to distant places in pursuit of their own careers: a return to Suriname for Johanna Helena and her husband, and for Dorothea Maria and her husband, a summons to St. Petersburg by none other than Peter the Great.

Kim Todd’s Chrysalis confronts what is perhaps the most enigmatic of all the questions raised by Maria Sibylla Merian’s remarkable career: How, in the end, did God fit into a natural world that her research revealed to her as radically different from what people had supposed? For an early user of the microscope, Father Athanasius Kircher, the miniature world under his lens bore witness to God’s infinite greatness. But what, Todd asks, about animals like the parasitic flies that Merian shows preying on the unsuspecting cocoons of butterflies? These beautiful winged beings will never fly; instead, they will be devoured from the inside out by maggots. For Darwin, such proof of nature’s savagery would cast him into despair.

For Merian, we have only the notes in her Study Book, dispassionately recording what happened rather than its part in God’s plan, just as we have only one brief statement, in a letter, that her married life was a source of unfathomable sadness. In their depictions of life’s cycles, moreover, the Merians, all of them, necessarily made use of specimens that were dead; only thus did their subjects hold still long enough to be painted accurately. In the end, it is the looming presence of death that makes these images so different from Leonardo’s drawings, which, with the exception of his human anatomies, attempt the impossible feat of capturing life in the act of being alive. For all its color and scientific clarity, Maria Sibylla Merian’s is ultimately a tragic art, suffused with a Calvinist sense of dire predestination rather than angelic metamorphosis.

This Issue

April 9, 2009

-

1

Olof Rudbeck Jr., Olavi Rudbeckii filii Ichthyologiae biblicae pars prima, de ave selav…non avem aliquam plumatam, nec locustam fuisse, sed potius quoddam piscis genus, manifestis demonstratur (Uppsala: Werner, 1705). ↩

-

2

Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age (University of Chicago Press, 2007). ↩

-

3

Women on the Margins: Three Seventeenth-Century Lives (Harvard University Press, 1995). ↩