Jerzy Kosinski’s collection of painful scenes is compared by his publishers with a set of Goya etchings: certainly the subject matter is comparable, in the cruelty of the events represented, but Goya used to add comments—reprimands, prayers, and curses. There is not much of this kind of feeling in Steps. On the dust jacket is quoted a 100-word extract of, no doubt, widespread appeal: it describes a naked woman imprisoned in a cage suspended from a ceiling. There are also rapes, persecutions, cruel revenges, and unjust executions. In its determination to avoid shallow feeling, Kosinski’s chill prose recalls Thom Gunn’s verse and similarly reflects the imagination of a postwar adolescence. (Kosinski was born in Poland in 1933.) “After the history has been made,” begins Gunn’s poem, Adolescence, which concludes:

When the lean creatures crawl out of

camps and in silence try to live,

I pass foundations of houses,

walking through the wet spring, my knees

drenched from high grass charged with water,

and am part, still, of the done war.

Kosinski’s cruel sketches do not specify a particular place or time: they lay claim to no roots, they are stranger’s tales. In the nightmare landscape of British fantasy, whether the Gothic arches harbor a hanging judge or Jack the Ripper, a ghost or a boarding-school, the frightened man knows where he is and looks around for friends. Kosinski’s surreal landscape combines aspects of Central Europe and the United States, impersonal countryside and ungoverned cities where strangers may gang up on you.

Turn, for a moment, to Up, a very different kind of book but containing comparable fantasies. Ronald Sukenick is more shy in his handling: he treats his bad dreams as grotesque and guilty porn, laughs them off in parody—while hinting at tearfulness. Up is surrealist, in a sense, being less a novel than a book about writing one, with the author and his characters defending or apologizing for it, discussing the next scene and celebrating its conclusion. There is little plot: what there is of it is cheerfully inconsistent and even self-contradictory. (In his own tough-talking version of Forster’s murmur against the tyranny of “story,” Sukenick remarks: “What the fuck I’m not writing a timetable.”) He regularly interrupts or stimulates his flow with dreams and anecdotes about cruel deeds—generally sexual atrocities which seem to relate to impressions of racial persecution by sadistic rednecks or blackshirts. A bar-room liar says: “That old sheriff made me strip naked and we had a little conversation with his hunting knife right under my balls. She was watching. Sure, they made her watch.” A few pages before, the narrator has dreamed of himself as a Super-Jew, disguised as a Nazi, rescuing a tear-stained nude whom the Germans have tied to a table. He whips out his circumcised penis and shoots the Nazis down: this fantasy may be taken as a salute to Norman Mailer.

The word “sadistic” has crept in. But, like “masochistic,” it seems out of date. These words are taken from the names of minor novelists of the last century whose principal interests seemed to be heterosexual partnerships in acts of real or simulated cruelty. I feel, without evidence, that interest in such ordeals comes from a different corner of our imagination than the area which is fascinated by mobs and gangs, lynch-law, gang-bangs, hooded Klansmen,, tar and feathers. Another Gunn verse:

Charles Baudelaire knew that the human heart

Associates with not the whole but part.

The parts are fetishes: invariable

Particularities which furnish hell.

You will note that the particularities offered in the preceding sentence were all American; but that tells nothing of the state of the world, only the state of my imagination. For some reason I can be entertained by a sick joke or a corny movie about American atrocities; but similar treatment of the Nazi equivalent provokes me to walk out or interrupt. Up combines these two areas (and more) of cruel dreaming with glimpses of reality in an edgy, inconclusive way.

The publishers of Steps invite the reader “into the darkest realm of existence…on a challenging journey into a lonely, harrowing region where the mind must find its own order.” No doubt there is some truth in this grandiose statement—the kind of advertising language which has helped to destroy poetry—but I don’t mean to press much further on the route indicated. Only to point out its relevance to two other novels. The principal character in Tell Me That You Love Me, Junie Moon is an American woman who has been made hideous by a maniac; first he made her strip naked while he insulted her and then, when she laughed at his quirk, he showered her with acid so that she had (in the whimsical words of the author) “a number of pitiful and pesky deformities…The crimson trench where the nose had been gave her face a bloody jack-o’-lantern look.” But the menace in the story is not the possibility of similar crimes but fear of the normal crowd who may persecute Junie Moon and her two (similarly deformed or disadvantaged) traveling companions. Thin snotty-nosed children surround their truck and call them beatniks and “the lady from outer space.” An adult in a red flowered shirt goes to tell the sheriff about the freaks. “His eyes were small and close together and his short bristly hair was cut so that the top of his head looked hard and narrow.”

Advertisement

The fear which the author is trying to illustrate is that which John Cowper Powys called “the American horror,” attempting to characterize this “phantasmagoric” intangible by reference to the Ku Klux Klan and to the burlesque shows of this century’s earlier years wherein, says Powys, he saw “tramps and beggars and cripples and imbeciles—all the derelicts in the great struggle ‘to make good’ held up to ferocious mockery.” Powys tries to generalize about the subject, referring to “the dominance of the big city over the country and the triumph of youth over age,” then to America’s “crude alliance between big business and the mob,” then to the nature of the “Lower Middle Class.” But he could not order these conjectures, which are better dealt with as anecdotes in imaginative fiction. Powys was no more precise, in his non-fiction, than Ronald Sukenick—who writes of Up: “I am trying to show, as exactly as possible, that American society is morally corrupt, spiritually exhausted, socio-economically unviable…It is not a question of America, really, it is just that this country seems at present to be the most advanced example of the human condition.”

The British reader is inclined to murmur: “Things are not so bad. Crazy Powys was renowned for wild exaggeration, and Sukenick is clearly reacting against the chauvinism of some of his compatriots.” But Sukenick’s outward gesture directs us to Janet Frame’s novel, a tale of persecution set in the mild and temperate welfare state of New Zealand. The victim is a British immigrant, a travel clerk who is pronounced dead after a traffic accident but who revives, weeks later, like Lazarus, and is treated as a freak. Godfrey Rainbird loses his job, can get no other, sits at home while neighbors stone his house and children chant: “Ole Cripply Rainbird’s dead an’ gone/ ‘s got no money for living on.” The polite thing to write would be that this is a fable about “the Individual versus Society”; but once the hypothesis of Godfrey’s resurrection is accepted, the attempt to work out the consequences fails to the point that the theme has been reduced, as so often, to a fantasist’s fear of the mob. To be cynical about it, some journalist would be bound to scoop up the story of poor Godfrey’s unjust treatment, simply for being pronounced dead, and Lazarus would be borne up in clouds of moral indignation.

There are some quite good things, though, in this novel: the characterization of “society” as an insurance company which “gives all the responsibility of living and dying over to money”; the quaint, punning, Joycean language which Godfrey uses on his return from the dead. But the narrative is generally marked by comically strained imagery breaking an urbane surface. Godfrey, an ill-educated man, quotes in his head lines from “some play he’d seen,” and the author comments, for him, “What was the play? Wasn’t there an old man on a heath in a storm?” Surely Godfrey knows whether or not he has seen King Lear. The New Zealanders are offered the performance of a Bach Passion—“but few people had the courage and ability to ascend the thin rungs to heaven; only giants climb beanstalks while Jacks cut them down; any ascent is a risk.” There is an absurd figure, about the flying bombs of Godfrey’s London childhood being like giant cigars and therefore reminding us of Churchill, “an explosive man, muddled but modern in his mythology, siren-suited with word music.”

Janet Frame seems to be patronizing the New Zealanders, pitying their lack of feeling for Art & Nature, while accusing them of improbable injustices. It is this air of well-meant condescension—an author congratulating herself on her own sensitivity—which also mars the highly praised Tell Me That You Love Me, Junie Moon. It is a moral fable in the style of Carson McCullers: it appeals to the young, and I have read a generous and eloquent appreciation of it, by a Yale student, rather in the manner of J. D. Salinger. He concludes: “And you admit that once Junie Moon tells you that she loves you, the ball flies over the fence. And you’re home free.” All we need is love-talk? Surely the shared weakness of these winning writers—McCullers, Salinger, and now Marjorie Kellogg—is their trick of persuading readers that they are not being sentimental, simply by introducing hard facts bluntly described, into a tale of easy tenderness. “When in doubt,” said the old thriller-writer, “have a man come in the room pointing a gun.” Another trick is to have a woman come in with no nose on her face, or have a woman cut off her breasts. A spoonful of medicine helps the sugar go down, with novelists who are praised for being “compassionate” or “deeply affecting.”

Advertisement

If the principal characters—one female, two male—had been pretty youngsters, dropping out, no one would be very impressed by their leaving a cold-hearted institution together and keeping house, like children playing a nice game, with little squabbles and cuddles. (Something like this happened in the movie, Rebel Without A Cause.) It is because they are all three so extravagantly crippled, deformed, mutilated, that we are expected to take the tenderness seriously. If the cripples had been just a little nearer to the general run of people—not so blatantly liable to provoke immediate aversion, then guilt, then pity—the author’s task would have been harder. A freak-show, however compassionate, is easy to run.

Obviously, if novelists were over-influenced by such reviewers’ arguments as these, they would never get a story written at all. This is probably what has happened to Ronald Sukenick. He introduces into Up a destructive review of “The Adventures of Strop Banally by RONALD SUKENICK.” and this review is the most convincing passage in the book. “The novel employs the by now quite conventional artifice of the plot narrative that no longer believes in itself as a means of approaching reality, and is not, therefore, meant to be taken very seriously.” (My italics.) This is partly a smack at the brusque judgments of reviewers, but it can also be used as an escape-hatch. Is Up “meant to be taken very seriously”? This passage sounds earnest—an extract from a life-like conversation between Sukenick and his friend, Bernie: “What remains of the intellectual reviews these days but an obsessive style, the critical twitch and analytic stutter of a leftover ideology, a habitual nasty snideness deprived of content and situation? Frederick Engels on sabbatical. It comes out like sour-tempered trivia. Hatchet jobs by snot-nosed careerists on their betters or stale grudges from the thirties.”

Possibly Sukenick does not wish (in James’s phrase) “to bring the exquisite before such a tribunal as this.” At any rate, he has gone to great lengths to avoid judgment. He has not taken such risks as Marjorie Kellogg or Janet Frame has done. Nobody is going to prove him wrong, to accuse him of sentimentality, of the wrong attitude to cruelty or tenderness, of lack of verisimilitude or (if the dialogue is taken as being instructive rather than representational) of weakness in argument, of lack of discipline or mishandling of images. He announces that he is not competing. What then is he trying to do? He claims no point of view. He says nothing straight: it is all in ironic parodies of ironic parodies, wisecracks about wisecracks. A barkeeper, “a nervous modern version of Chaucer’s canny host” (parody?) “had cultivated a lumpenintelligentsia clientele” (straight?) “whose beards had totally displaced the red noses of indigenous Polack rummies” (straight? parody?). Sukenick rhapsodizes about the solid wood of the bar counter: “in being so absolutely there, the bar communicated to me an absolute sense of my own presence.” Then (or probably before he started) he thinks “pretentious, narcissistic” and continues, “It was a feeling very similar to the one from which derived a peculiar hobby of mine, that of collecting photographs of myself. I also sometimes got it after a good lay. But not always I thought of Nancy.”

With so self-conscious and self-critical a writer, it is not surprising that he has failed to write The Adventures of Strop Banally: he knows what the reviews would be like. The fictional reviewer describes Banally as “a ferocious rascal who trades on his irresistible sexual appeal, his All-American appearance, and an incredible competitive drive for power.” The reviewer holds that Sukenick can never succeed “in entering imaginatively into the identity of his hero. One wonders why he should ever wish to do so…The author seeks nothing less than a prostitution of himself and the rape of what he desires.” Instead of writing the straightforward “rebellious farce” then, Sukenick introduces Banally only as a disgusting fantasy figure, trailing clouds of psychopathology from the Times Square bookshops. In the more “realworld” parts of the story, we find Sukenick trying to be picaresque, trying to be merry about the machinations of a crooked car dealer, trying to befriend tough-minded working-men—who turn out to have fascist minds. How can he end on a positive note?

Sukenick describes himself lecturing on Wordsworth, and how his words inspire the students to run out into the streets to create true democracy—but he knows this is fantasy, so he makes it silly, ends with a party for his old school friends and a burst of defiance against the reader. He’s not telling any secrets. “You want to find out about my personal life give me a ring I’m in the book.” He has given nothing away.

After this, Steps, re-read, seems more impressive than it did at first. It stands above Up, as Pride does above Vanity. While Sukenick has been so desperately avoiding the sloppy niceness of the ethical values of Kellogg and Frame, spluttering ineffectually about his failure to identify with Strop Banally through fear of banality, Kosinski presents in his narrator a Strop with whom we can identify very easily, a man concerned with success and failure, who uses words for what they immediately mean without clotted ironies and allusions: the reader may apply his own moral judgments, if he wishes, without the conventional signposts or Sukenick’s traps and mazes.

The narrator in all his anecdotes, as ski-instructor, soldier, lover, shipyard-worker, is willful, wanton, whether following cruel or humane desires. In order to live among a group of dark-skinned slum-dwellers in an “underdeveloped” country (unspecified) without being excluded from their customs and society, he pretends to be deaf and dumb. This is what he wants to do, not what he thinks good. Sometimes he does other things as he chooses, which we will think bad. Between the anecdotes there are occasional patches of dialogue, in italics, usually a conversation between the narrator and a woman: here, questions of right and wrong sometimes crop up, as when the woman asks if circumcision is not cruel. This makes an odd juxtaposition with the surrounding anecdotes about death in the army. Their freedom from the language of shock and moral outrage reminds us how stiff with ethical truisms is even the barest newspaper report, and we feel refreshed by Kosinski’s austerity. Thus when the narrator for once questions a sin of omission, asking a priest: “Of what value has your stewardship been to the people of this village? Of what value is the religion which you so commend to the people of this community?”—the inquiry has greater weight because of its rarity.

It is the simplicity—unforced, unironic—of the English used that distinguishes Steps. Take a random paragraph: “I touched her uniform and knelt in front of her. I lifted her skirt. The starched fabric crackled. She was naked beneath; I pressed my face into her, my body throbbing with the force which makes trees reach upward to drive out blossoms from small, shrunken buds. I was young.” Think of the ornamentation which Frame, Kellogg, and, most of all, Sukenick would have added to this interesting passage. The language used is especially appropriate for one of the narrator’s principal concerns—the relation between planning and spontaneity in human life, particularly in sexual congress. The narrator goes with a heavily painted woman, who turns out to be a man in disguise. He says: “…everything had suddenly become very predictable. All we could do was to exist for each other solely as a reminder of the self.” This kind of simplicity is not naïve. There is another passage, where his woman is describing another sexual encounter, which reads equally well if you count the syllables and set it down as verse:

Yes, but it could not be planned.

I liked him;

it was spontaneous. And because

it was that, it became a good test:

it answered the questions I asked

myself.

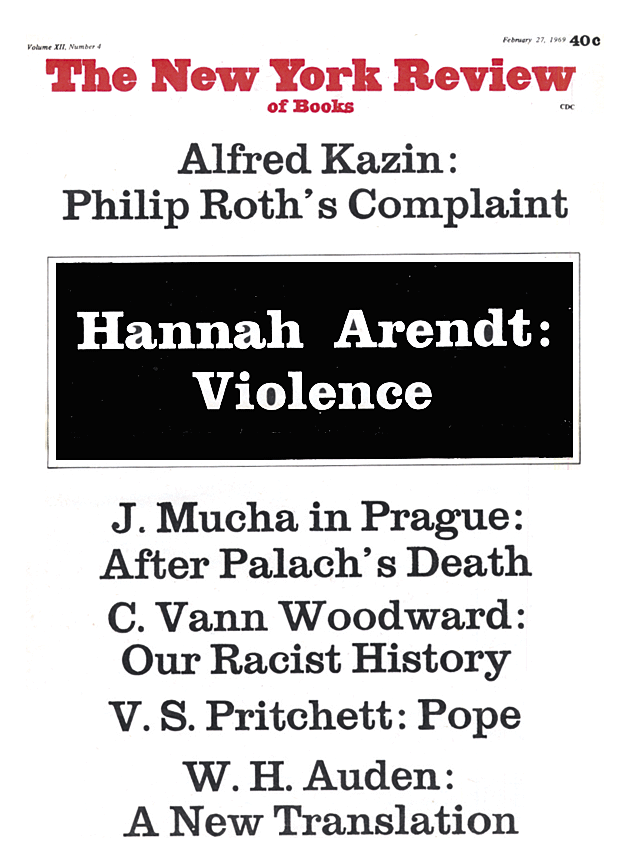

This Issue

February 27, 1969