Soon it will be the twentieth anniversary of the death of Stalin, and the chances are growing that he, rather than the liberation that followed his death, will be celebrated. The liberation was real; under Stalin the Soviet intelligentsia simply were unable to read such books of protest as this one by Zhores Medvedev, the Soviet biochemist whose book on Lysenko also appeared in the West two years ago.1 But the freedom has been stunted. Intellectuals see such books now only in samizdat, “self-publication” in typed or photographed copies passed about cautiously among friends, as were Medvedev’s book on Lysenko and the papers in this book.

Although no law forbids this practice, many people have been threatened, fired, and even thrown in jails and madhouses for participating in this method of evading prepublication censorship. When one reflects that more than a century has passed since a tsar promised the end of prepublication censorship on most books, the present situation seems more than merely strange. It suggests an eternal curse on the Russian intelligentsia, which seems doomed to Sisyphean struggle for elementary rights that are elsewhere taken for granted.

Watching from afar we tend to see only the periodic clashes between political bosses and a few famous writers. We are inclined to forget that these fierce dramas are staged not only because the bosses are stupidly fearful, but also because the artists’ fictions bring to unbearable focus the multitude of humiliations that one must silently swallow to make a career for oneself or sometimes even to survive. Of course there are humiliating hierarchies all over the world, which is one of the main reasons for the world-wide appeal of Russian literature. But Derzhimorda (literally, “Hold-the-snout”), a type of boss named by Gogol in 1836 and still a byword, has been especially characteristic of Russia. In this book Medvedev tells what happens when such men are in power.

In Obninsk, the town where Medvedev worked, a ninth-grader commented, in a composition on Pushkin:

The methods of dealing with dissidents and writers in Pushkin’s time were the same as today. There were informers, libels, and secret surveillance. But everything was simpler then, you could challenge your opponent to a duel. [P. 400.]

The consequences of this schoolboy’s comments are even more revealing of the peculiar situation in his homeland. The local chief of ideology heard about the “anti-Soviet” comment from his wife, a teacher in the school, who heard the other teachers talking about it. The ideological boss started an investigation, with the result that the other teachers were officially reprimanded for failing to report the incident; the boy’s father, an editor of the local newspaper, was expelled from the Party and dismissed from his job. The reprimanded teachers made a little gesture of protest: they stopped speaking to the informer, who had to be transferred, but her husband remained the local boss of ideology.

In that capacity he arranged for the dismissal of other suspect intellectuals, including Medvedev, head of a biochemical laboratory in a local research institute. At the time Medvedev’s chief sins were his samizdat history of the Lysenko affair and strenuous objections to interference with his mail. When he used his enforced idleness to write two more samizdat works, which are combined to form the present book, Medvedev was seized by the police, without a warrant, and put into a madhouse. Vigorous protests by prominent scientists and writers won him release and a new job, though a poorer one.

This story, including not only the silent indignation of the teachers and the improbable victory of the protesters but also the persistent triumphs of the local boss, could easily be a tale by any number of post-Stalin writers, from the reformed Ehrenburg to the incorruptible Solzhenitsyn—which shows how literal, how close to reportage, their stories are. The Medvedev Papers is a calm factual account of institutionalized tyranny, complete with names, dates, and verbatim quotes. The tyrants are secretive bureaucrats, like the “little man with a professionally censorious look”2 who came into the institute and took the director’s chair at the meeting that decided Medvedev’s dismissal. The little man turned out to be the town’s ideological boss.

Medvedev’s descriptions of the daily conflict between the bosses and the intelligentsia are fascinating. More important, by dogged research he has made genuine discoveries about two of the causes of keen discontent among the intelligentsia: restrictions on foreign travel and surveillance of the mails.

The rules for the issuance of foreign passports are a state secret. That astonishing fact, discovered with great difficulty and retailed to the reader with the mystery writer’s technique of suspenseful delay, obliged Medvedev to reconstruct the rules by careful study of their application. He used, as he drily remarks, the logic of chemical analysis, determining what is in the compound through study of its reactions. His principal reagent was himself—a good one, too, for he has been repeatedly invited abroad: to participate in symposia, to give lectures, to engage in joint research. (He is a distinguished biochemist, though he insists that he is an ordinary one. He is a genuinely modest man whose jailers, in the madhouse where he was confined, tried to show he had delusions of grandeur.)

Advertisement

He also collected the experiences of his scientific acquaintances, and used his keen sense of human feelings when he happened to witness a number of revealing events. While waiting in a Moscow office one day, he saw a group of bureaucrats bring a Georgian professor to the verge of collapse by denying him his documents the day before he was to make a scheduled trip to a foreign conference. After the dazed victim had stumbled out the door, the bureaucrats laughed.

Feelings aside, here in simplified outline is Medvedev’s table of steps to be taken before a foreign trip, whether for business or pleasure. The applicant must:

- fill out questionnaires covering his entire life, his extended family relationships (enclosing copies of marriage certificates and children’s birth certificates), and his proposed itinerary;

- submit a character reference attesting to his political maturity and moral stability, which must be endorsed in triplicate by all his superiors at his place of employment, by a meeting of the Party bureau in his locality, and by a meeting of the regional (raion) Party bureau;

- all of which must then be endorsed by an appropriate section of the Party’s Central Committee (Science and Higher Education in Medvedev’s case), and

-

by the Exit Commission of the Central Committee, which checks the applicant’s record with the Committee on State Security (KGB). Then

-

the Ministry of Foreign Affairs may prepare a foreign passport for him, but

-

he must be instructed on behavior abroad, at a personal interview with an employee of the Central Committee in Moscow, just before he receives his documents and departs.

The entire procedure must be repeated for each trip abroad. Is it any wonder that the bureaucrats who made these rules keep them hidden?

Perhaps the greatest triumph of Medvedev’s ingenious reconstruction of secret rules occurs in his study of the mails. He discovered that every letter going into or out of the Soviet Union is secretly opened, read, and resealed by a special bureau. I must apologize for spoiling once again the suspense of a dramatic disclosure that Medvedev skillfully makes. The suspense might have been lost anyway on Western readers who do not share the assumption of the Soviet intelligentsia that selective scrutiny is the reason for the terrible delay in foreign mail. That there should be total scrutiny seems impossible to accept, until one has followed Medvedev in his struggle to get past the hidden authorities three letters that they were determined to stop.

The addressees in England and America kept him informed, by other letters and postcards, that they were failing to receive the three letters in question. At first in anger, then with the growing fascination of a scientist on the brink of a discovery that his prior assumptions had precluded, Medvedev devised all sorts of ingenious experiments. He mailed the three letters from scattered points in different cities at different times, with different handwritings and return addresses, without return addresses, registered and unregistered, and enclosed with other letters which reached their destinations without the enclosures. The three banned letters were invariably discovered and stopped.

My favorites among Medvedev’s postal experiments are those that relied on Supercement, a glue that makes an envelope impervious to steam. The hidden reader was therefore obliged to tear the envelope and then patch it as best he could. Thus Medvedev was able to prove that there is only selective scrutiny of internal mail—it applies to letters mailed in foreign envelopes and to suspect individuals like Solzhenitsyn—but total scrutiny still proved to be the rule at the frontier. He sent reprints, for example, to nonexistent addresses in England, one in an envelope selaed with ordinary glue, the other with Supercement. They were returned to the experimenter in due course, one in excellent condition, the other torn and patched.

Medvedev’s law of mail scrutiny is subject to a major qualification. Though all foreign correspondence is opened and looked at, all of it cannot possibly be read with genuine comprehension. Indeed the stupidity and capriciousness of the hidden censors is one of Medvedev’s main complaints against them. On this point his chief evidence is the treatment of foreign printed matter by a group of censors who are a shade less secretive than the ones who read letters. The censors for printed matter leave their individually numbered stamps on items, like inspectors in a factory, who may be called to account for items they pass (with an angular mark) or prohibit (with a hexagon).

In this connection Medvedev coolly reveals another fact that seems unbelievable. Most Soviet subscribers to foreign scientific journals, libraries as well as individuals, do not receive the issues as printed abroad. They receive photographic copies, manufactured in the Soviet Union after the corps of censors has excised every item of a possibly suspect nature. Approximately 500 scientific journals are passed through this monstrous filter. It hardly needs to be said that they arrive very late (approximately six months), or that they are journals of natural science and technology, which have relatively few items to be excised. (Science, for example, is regularly stripped of articles on science policy, of book reviews on Russian subjects, even of letters to the editor denouncing US intervention in Vietnam.)

Advertisement

The overwhelming majority of foreign publications in the fields of social science, the humanities, and public affairs are simply denied to the Soviet intelligentsia. If they are imported at all, they are stamped with the prohibitive hexagon and deposited in “special holdings,” where they may be seen only by properly authorized personnel.

One of the most astonishing qualities of this book is Medvedev’s calmly reasonable tone as he examines these horrors. (I have mentioned only a few of them.) Mild irony is his characteristic method of expressing his feelings, and such passages are relatively infrequent. Most of all he is concerned not to denounce, but to explain, to persuade his Soviet readers of the necessity of reform.

Here lies the one serious weakness of his book. Medvedev regards stupidity and privation as the main causes of conflict and tyranny. It follows that the application of intelligence and the achievement of abundance are the cure. Therefore scientists and technologists, and the “creative intelligentsia” in general, are the chief force for peace and progress in a world of converging social systems. This is very like the social philosophy of Andrei Sakharov, the renowned physicist who startled the Soviet bosses with his essay Progress, Coexistence and Intellectual Freedom.3

The outlook of both scientists is so refreshingly sweet, so plainly and simply good, that one hardly has the heart to point out its inadequacy. Fuming or brooding over the world’s incurably wicked complexity turns very easily into self-destructive rage or self-serving quietism. Medvedev’s faith in science is immune to those diseases.

The suborned psychiatrists who tried to commit Medvedev last year attempted in vain to pin on him a syndrome they have invented, “reformer’s frenzy” (reformatorskii bred). A wilder misreading of his personality cannot be conceived. He is a soft-spoken, gentle man with a slight stoop and a faintly comic shuffle. Serene in his faith that both humanity and the Soviet system are amenable to gradual improvement, he calmly perseveres in his biochemical studies of aging, which occupy most of his time, and in unanswerable exposés of stupid tyranny. An earlier generation of the Russian intelligentsia would have said that he is committed to the heroism of little deeds. In these harsher times his acts of heroism cannot be called little.

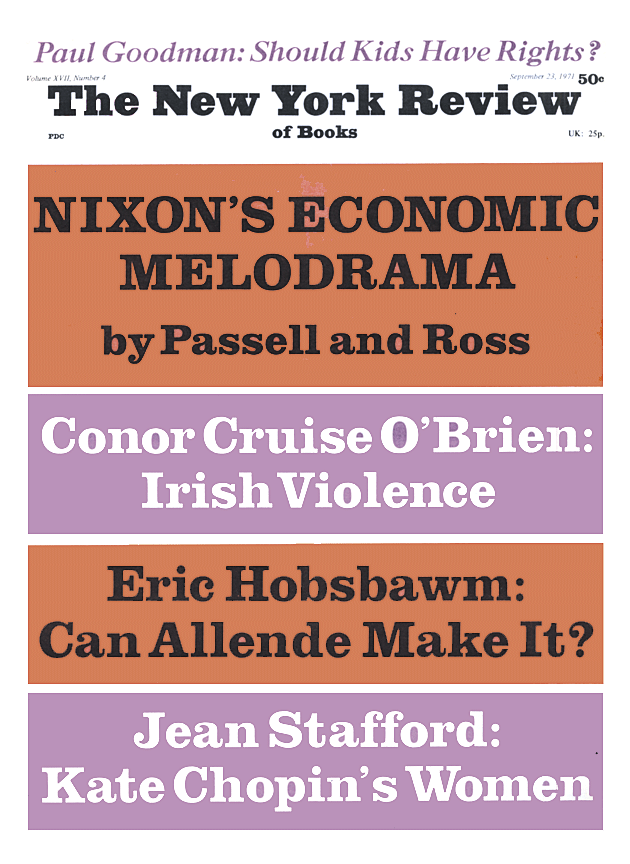

This Issue

September 23, 1971

-

1

The Rise and Fall of T. D. Lysenko (Columbia University Press, $10.00). See my review in NYR, January 29, 1970. ↩

-

2

The translator chose “mordant” rather than “censorious,” but that is a trivial error for someone who turns “raising his voice” into “hanging his head” (p. 449, and p. 144b of the Russian edition [St. Martin’s Press]: Mezhdunarodnoe sotrudnichestvo uchenykh i natsional’nye granitsy, i Taina perepiski okhraniaetsia zakonom). Howlers are scattered throughout the book. “Miscalculation” becomes “calculation” (p. 145); “surplus value” is “additional cost” (p. 163); “Republic of South Africa” is “United Arab Republic” (p. 169); “The British Ally” is “The British Unionist” (p. 230); “clinical” is “chemical” and “schedule” is “graph” (p. 401). ↩

-

3

Norton, 1968. ↩