Constantine Cavafy (born 1863 and died 1933) lived in Alexandria (where during the First World War E. M. Forster, employed by the British Red Cross, knew him). He lived and wrote, as befits an Alexandrian, on the edge of modern as well as of classical Greek civilization and of the European symbolist and decadent literature of his time. And yet he seems in some early-Eliotish way at the hidden center of our own time. His poetry might have come out of a shadowy corner of Yeats’s Byzantium. His imagination, as Rex Warner explains in his excellent Introduction to John Mavrogordato’s translation of his poems from the Greek,* finds its themes “in the Hellenistic blending of cultures and races in cities like Alexandria or Antioch where Greek and Jew, pagan and Christian, sophist, priest, and barbarian form a complicated and far from Periclean pattern.” One might add to the cities mentioned The Waste Land’s “Jerusalem Albens Alexandria/Vienna London/Unreal” and, to them, New York, to throw light on the magnetic pull Cavafy has for us.

“There is a tide in the affairs of men / Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune.” These are, surely, the last lines that one would think of in connection with Cavafy’s poetry, which is so far from the world of empire, Caesars, principalities, and powers. Cavafy writes not about Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra and Octavius in their ascendancy, but about Caesarion’s failure and effeteness, the late Romans waiting with longing for the barbarians, the gods forsaking Antony. His world is the opposite of the tide that leads to fortune; but if one inverts Shakespeare’s lines, reads them backward as it were, they throw a sudden light on his poetry. “There is a tide in the affairs of men / Which, taken at the ebb, leads to misfortune.” Cavafy’s main concern is with those who didn’t go out on the tide, or who were left behind, or swept back by it.

He is particularly fascinated by the idea of the moment of choice, of misfortune or disgrace. What his great poems about disastrous moments in classical history and the Greek or Roman worlds in their decadence and his small poems about situations of private depravity have in common is the fascinated sense of the die being cast with fatal results which are still exquisite in the moment of the casting. This is what Antony, at the moment of the choice that leads him to be forsaken by the gods, and the depraved practitioner of “Hellenic love” in a male brothel have in common.

So his poetry is peculiarly about situations that lead—or have led—to ruin. He immortalizes the moment at which the predestined disaster or corruption happened. The reason why this poetry, even in translation, seizes our imaginations (so much that those who love it regard it almost as they would a secret addiction) is that it reaches that part of our consciousness which goes back and thinks, “Just then I might have made the fatal choice which would have led to my ruin but would have realized my true nature.” Of all poets he is the one who most makes success look like grandiose failure and failure look like hidden fatal success. Far more than Baudelaire, he knows that to fall over the abyss is an easy price to pay for snatching at the flower of evil.

Eliot must have known moments like those that make up Cavafy’s world: The awful daring of a moment’s surrender! By golly, though, he didn’t surrender! He became an Englishman. All the same, Eliot is near to Cavafy in his realization of the choice not taken which may seem even realer than that taken:

the memory

Down the passage which we did not take

Towards the door we never opened

Into the rose garden.

Most critics tend to divide Cavafy’s poems into the “erotic” and the “historic,” or as Rex Warner puts it in his Introduction: “The sources of his inspiration are the byways of ancient history and what to most people would appear as scandalous love affairs.” These have in common not just themes of “decadence” but their concern with actions, or inactions, that lead to misfortune, but that in themselves have a reality independent of these results. Cavafy strips past historic events of their moralizing consequences, and thus he is able to view as a pure situation that which the world regards not just as immorality but as deplorable failure. He has a vision of the historic past but refuses to exercise that “historic sense” which consists of judging past action by whether it later led to success or failure. He would not have agreed that “History to the defeated / May say Alas but cannot help or pardon.” He gives to the defeated the two cheers that E. M. Forster gave to democracy.

Advertisement

This, then, is the link between Cavafy’s historic and his erotic poems. Both are about the place where the dream crosses with the moment of action, which Cavafy releases from the guilt of the results and judges in its “pure,” un-future-burdened state. This is surely the significance of “King Claudius,” the poem about Hamlet, a subject which Edmund Keeley and George Savidis consider, in their Introduction to Passions and Ancient Days, so far “beyond the boundaries of Cavafy’s world.” Purely as a subject this is perhaps true. But Cavafy’s treatment of Claudius is both ingenious and characteristic: ingenious as an application of Edmund Wilson’s idea about The Turn of the Screw—that all the dirt went on in the governess’s mind and the children were quite innocent. The character of Hamlet is to Cavafy as that of the governess is to Wilson. Hamlet’s “case” against the King consists entirely of “evidence” that goes on in Hamlet’s own mind, supported only by hallucination, the ghost. Claudius was really a kind and good king much liked by the people, and the only person who agreed with Hamlet was Fortinbras who, in doing so, was a highly interested party.

However, an ingenious theory does not explain why “King Claudius” has Cavafy’s peculiar quality. It has it, I think, because the theory provides Cavafy with the excuse of stripping Claudius of a “future” that Hamlet imposed on him and of considering him simply in the separateness of his own being, before fatal choices had been made for him. Viewed in this light, before any of the consequences of a historic action had been incurred, Claudius appears to be an amiable and well-liked king.

In his erotic as in his historic poems Cavafy adopts the same procedure, which is to separate out the squalid and depraved circumstances of a life that constitute its future and to make one see the person involved as someone who simply exists as a being, before he has made a choice, or before its consequences have become operative. Or if they have happened, then Cavafy makes us see the person concealed within them, like a bullet in a body detected in an X-ray photograph. In doing this he reveals, of course, not just a private obsession but also a moral attitude, very concentrated and intense, even if limited. Thus he addresses the figure in a pornographic photograph:

Who knows what a degrading, vulgar life you lead;

How horrible the surroundings must have been

when you posed to have the picture taken;

what a cheap soul you must have.

But in spite of all this, and even more, you remain for me

the dream-like face, the figure

shaped for and dedicated to Hel- lenic love—

that’s how you remain for me

and how my poetry speaks of you.

The ambiguity of the poem rests in the idea of the moment when the boy posed to have his picture taken. Although he was surrounded by all the signs of his degradation, these stage properties represent a future and not what he “is.” He is “the dream-like face,” “Hellenic love,” poetry of existence untainted by the consequences. Cavafy’s magic lies in playing off the idea of unalterable existence (what I call the moment of choice which precedes the consequences) against a future which essentially he regards as vulgar and irrelevant.

He is the master poet of lost opportunity, reminding each reader separately of a moment, for example, when he was quite young and stood outside a travel bureau looking through the window at leaflets and photographs inside. A stranger came and stood beside him, also looking through the window at the same trashy documents. Reflected in the plate glass, their eyes met and, when each moved slightly, their lips even crossed; and neither dared speak, and they walked away in different directions, each alone. But one—perhaps both—relives that moment during many wakeful nights, the ideal beginning of the ideal journey never taken.

This situation, this passionate attachment to an unfulfilled past which makes Cavafy claim sometimes that the erotic memory or wish is realer than the actuality of love—and makes him falsely identify it with poetry—finds its most complete reflection in the homosexuality which is the projection onto another of a dream which is oneself. For this reason, Cavafy’s historic poems are rightly considered better than his erotic ones; but they reveal the same fixation on a particular moment.

Cavafy is, of course, of his time, pre-eminently the fin de siècle. His values are erotic because they are aesthetic (John Donne observed that he who loves beauty beyond all else “beauty in boyes and beasts will find”). What the moments of his obsession all add up to is best conveyed in the word “beauty.” When one says this one means that Cavafy not only “lived” for beauty but he worked to create it in his poetry. The editors, in their Introduction, show how he would work for years over one of these simple-seeming poems, and how he was never sufficiently satisfied with them to produce a collected volume during his lifetime. He published his poems separately in magazines, keeping off-prints of them in folders. He selected two volumes of these off-prints, the contents of which his heirs considered to constitute the canon of his work. The poems here translated were excluded from these volumes. Among them are some of his most interesting poems. The Introduction, translations, and notes are excellent.

Advertisement

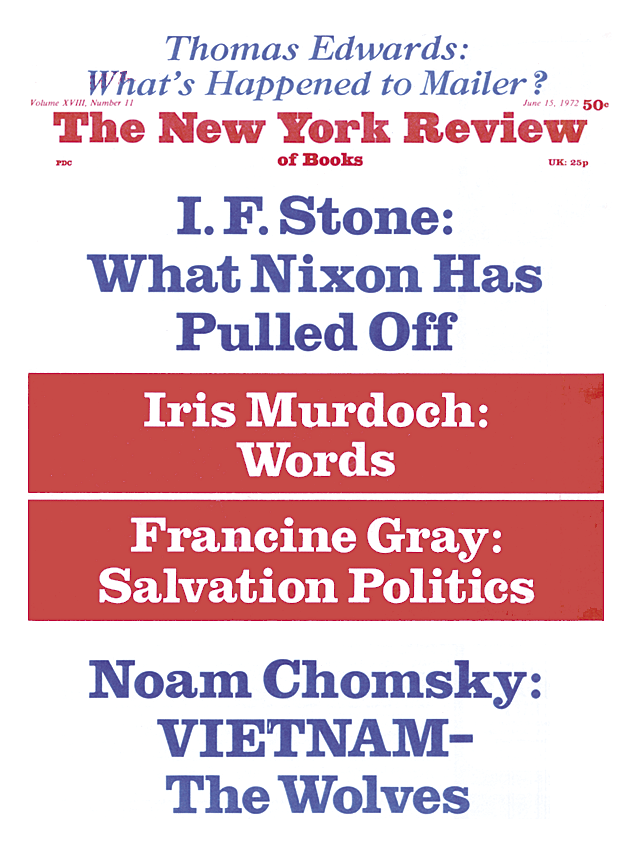

This Issue

June 15, 1972

-

*

Poems by C. P. Cavafy (London: Chatto & Windus, 1971). ↩