In response to:

The World Behind Watergate from the May 3, 1973 issue

To the Editors:

In “The World Behind Watergate” [NYR, May 3], Kirk Sale asks interesting questions about power in America. But he confuses the answers by stressing a supposed split between the self-made “cowboys” of the Southern sunbelt and the more refined “yankees” of old Eastern money.

It is, of course, significant that Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon have given newer sections of the country access to the levers of power. The New Frontiersmen came from Harvard, Haldeman and Ehrlichman from UCLA. But if the new-school ties explain Watergate, how should we explain John F. Kennedy’s open purchase of votes in the 1960 West Virginia primary or his brother Bobby’s abuse of government power to “get” Jimmy Hoffa?

We could, I suppose, brand the Daley Machine in Chicago or Harry Truman and the old Pendergast Machine un-yankee, if also un-cowboy. But no one was more yankee than Robert Taft and John Foster Dulles, both of whom encouraged Senator Joe McCarthy and his obvious use of perjured testimony. Sale also forgets the dirty, but I guess legal, tricks of the Eastern Establishmentarians revealed in the Pentagon Papers and earlier exposés of CIA skulduggery. Hunt, Barker, and McCord might be CIA veterans, but their CIA bosses were the aristocratic Allen Dulles and Richard Bissell.

Sectional differences might account for much else. But to impute uncommonly slack standards to the cowboys of the Southern rim is silly, or if the Yankee Doodle fits, self-serving.

Nor do the cowboys hold any monopoly on defense contracts, influence-peddling or shady speculation. Defense plants do dot the sunny South, and do shape employment and voting patterns. But ownership and control of the “military-industrial complex” seems to be in the hands of the old-money yankees, who show a most unrefined taste for the government trough. It wasn’t the sunburned aerospace execs who got Lockheed the big government loan, it was their bankers, their Wall Street bankers. Sale admits that the New York bankers and investment houses are moving into Southern industry. But, in the case of defense industry, they’ve been there from the start, as a brief review of the corporate histories shows. ITT is, of course, an old-line company turned conglomerate; its chief Harold Geneen is considered one of America’s most professional managers; and its board contains both cowboys like George R. Brown (of Brown & Root) and “yankees” like Felix Rohatyn (of Lazard Freres) and Eugene Black (director of several Rockefeller corporations and former president of the World Bank).

The big contributions to presidential campaigns raise a more serious question for power structure researchers, and one which is not easily answered. My own guess is that they are only a secondary route to influence. Southerners, Westerners, nouveau riche probably do contribute an undue share of the money, in this and in past elections. But that seems to be because they are still more out than in. Texas oil gives money; Peter Flanigan of Wall Street’s Dillon, Read masterminds White House energy policy.

Nixon’s inner circle—Bebe Rebozo and the other self-mades—seems similarly peripheral to the big decisions. More important, if Nixon and Roy Ash can institutionalize their centralization of government, such relatively small people will need a President’s friendship to compete with the institutionalized influence of the Rockefellers and Fords.

Overall, Sale is too quick to read political significance into “ties” and “links.” “Soybean king” Dwayne Andreas might have “a home and investments in Florida and ties to Southern money,” but to the extent his power is regional—and not national—his base is Minneapolis-St. Paul, as Hubert Humphrey could explain. It is a similarly long hop from South Carolina to South California, from textiles to oil wells. Were the nouveau riche Southern Californians who bankrolled McGovern really part of a cowboy conspiracy to pick a Democratic loser and thereby help Reelect the President? Are such sunshine belt senators as Cranston, Tunney, Goldwater, and Ervin simply part of a sophisticated post-Watergate cover-up?

Steve Weissman

La Jolla, California

Kirkpatrick Sale replies:

It’s rather difficult to figure out what Steve Weissman is trying to get to in his zig-zaggy letter, but I don’t really think there is any serious disagreement between us. He agrees with me that the emergence to power of the Southern rimsters is “significant,” concedes they give a lot of political money, and recognizes that they are the people close to the President. And I agree with him, as I said in the original piece, that the Eastern establishment has a lot of power in this country and that it is quite capable of dirty tricks.

We do seem to have differing points of emphasis. I find the degree to which Southern rimsters have come to exercise power a new and essentially overlooked phenomenon, a major shift in the economic and political picture over the last decade or so; Steve, if I read him right, suggests that insofar as such a shift has taken place it doesn’t mean anything, since the whole lot of them are no-goodniks anyway. I believe that the new-money aerospace executives and independent oilmen and PR hustlers have brought new attitudes and styles to the top levels of government, as the repression of the left and the Watergate scandal bear witness; Steve apparently feels, along with some current Republican letter-to-the-editor writers, that nothing has |changed much from the days of Truman.

But of course I did not try to claim that all politicians before Nixon were pure of heart, that Harold Geneen was some cowboy finagler, or that all Southern rimsters were in Nixon’s pocket, and if that’s what Steve thinks, I recommend he reread the article with somewhat more care.

I’d like to elaborate on several smaller points.

- I don’t know how Steve is measuring “ownership” of the “military-industrial complex,” but the fact is that most of the top defense contractors are Southern rim firms with Southern rim executives, which do their primary business in this region (e.g., of the top ten, Lockheed, McDonnell Douglas, General Dynamics, Tenneco, LTV, and Litton) as do many other defense giants (e.g., Textron, North American Rockwell, Martin Marietta, Texas Instruments, etc.). As to those nefarious Wall Street bankers, they undoubtedly have an interest here, but they neither own nor control these companies; taking as examples the top two defense firms, the amount of outside institutional ownership is small (for Lockheed, 350,000 out of 11 million shares, for McDonnell-Douglas, 3.6 million out of 30 million shares), while outside financing, even including short-term loans, amounts to less than a decisive percentage of their liabilities (for Lockheed, $532 million out of $1.5 billion, for McDonnell, $496 million out of $2.1 billion).

Some idea of the importance to the defense industry of the South (leaving aside the equal importance of the Southwest) is suggested in a new periodical, Southern Exposure (Vol. 1, No. 1, published by the Institute for Southern Studies, 88 Walton Street, NW, Atlanta, Georgia), which shows that the South received 38 percent of the Defense Department procurement budget in 1971 though it has only a quarter of the total population, and that the defense industry is the largest employer in the states of Louisiana, Georgia, Mississippi, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia.

- Lockheed’s governmental loan was not secured by Wall Street, attractive as that kind of Krokodil theory may be, but by the public and politicians and pressures of Southern California, faced with the dislocations and unemployment which a Lockheed retrenchment would bring.

- It is a mistake to think that Peter Flanigan “masterminds” energy policy, despite his participation on several White House policy boards and his one-time participation in a tanker company working for Union Oil of California. Nixon is much more likely to listen to John Connally, friend of the Texas oil interests, or Fred Hartley and Claude Brinegar of Union Oil (the latter now Secretary of Transportation), or Deputy Treasury Secretary William Simon, chairman of the Oil Policy Committee. And he is hardly likely to give a great deal of credence to a person who has shown himself to be more dummy than ventriloquist, as in Flanigan’s ITT performance where he meekly did the bidding of Nixon, C. Arnhold Smith, and John Mitchell in approving the ITT-Hartford Fire merger in return for that $400,000 campaign gift.

-

Though presidential friendship may seem to Steve to be a small matter, it is clearly the way toward that “institutionalized influence” he sees among the Rockefellers, and the way is paved with a lot more than trivia, as John Connally can attest. Connally, according to the recent profile by Joseph Kraft (New York, May 28), gained “literally millions” when Nixon lauded him as his unofficial oil adviser and has brought both clients and money to his law firm as a result of his intimacy with the President; and it is hardly a coincidence that the new multi-million dollar gas deal with the Soviet Union is going to Connally’s client Occidental Petroleum, that the construction is to be done by Connally’s client Brown & Root, that some of the necessary tankers are to be built by Connally’s client Texas Eastern, and that a major financer of the deal is Connally’s client the First City National Bank of Houston.

Something clearly is shifting in our national “power structure,” and awareness of the old and still-potent centers of it should not blind us to the major role of the new and expanding components.

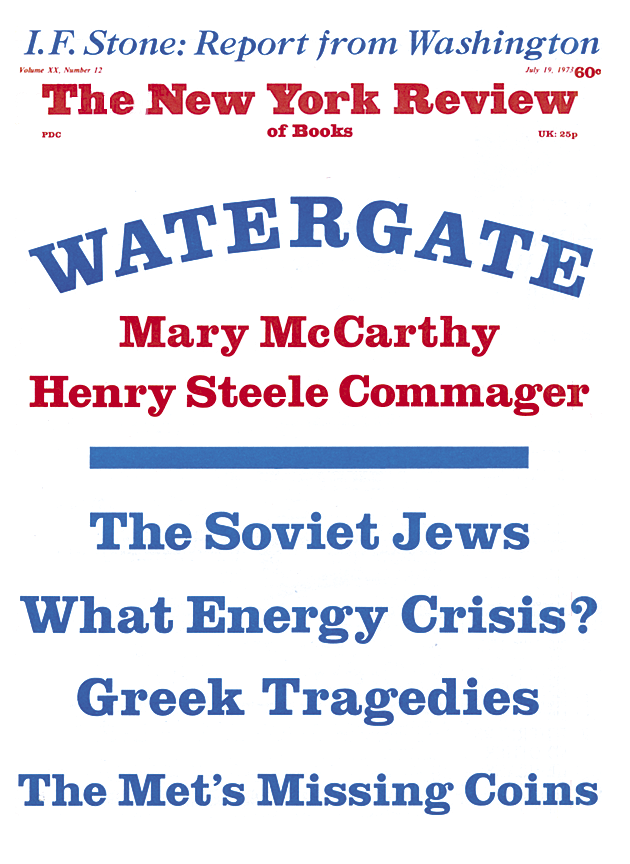

This Issue

July 19, 1973